Ahead of Its Time, Behind the Curve: Why Evernote Failed to Realize Its Potential

Legendary investor, programmer, and Y Combinator co-founder Paul Graham once wrote that one of the best ways to come up with ideas for your next startup is to ask what product you wish someone else would make for you.

For Stepan Pachikov, founder of Evernote, that product was a way to help him remember things.

Although Pachikov first began working on what ultimately became Evernote back in 2002, his fascination with human memory stems from his experiences growing up in the former Soviet Union. To Pachikov, Evernote wasn’t just another app or a way to capitalize on Silicon Valley’s burgeoning obsession with personal productivity. It was an extension of the human mind itself that would let users remember everything.

Evernote has come a long way since Pachikov began working on the app seventeen years ago. Evernote was and remains one of the best examples of what a freemium product can be. Despite this, Evernote has been plagued by a series of managerial missteps and failed product launches, and the company’s future is far from certain.

Here are some of the things I’ll be exploring in this article:

- Why timing was so crucial to Evernote’s success, and how co-founder and former CEO Phil Libin’s vision for the product created vital tailwind for Evernote’s growth

- How the company resisted investor pressure and remained true to their convictions about the value of Evernote as a freemium product

- How Evernote lost sight of its original vision and how this almost doomed the company

The idea for Evernote began with the personal quest of its founder, Stepan Pachikov. He aimed to solve a giant problem: overcoming the limitations of human memory.

2008-2011: Creating an Impossible Vision

Stepan Pachikov wanted to remember everything.

Pachikov is one of Silicon Valley’s most visionary technologists. A pioneer of virtual reality, computerized handwriting analysis, and optical character recognition, Pachikov has spent much of his life working to solve some of computing’s most challenging problems.

Trained in economic mathematics, Pachikov earned his doctorate in fuzzy logic from the Academy of Sciences of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in Moscow. As a scientist living and working under Communist rule in Soviet Russia, Pachikov was no stranger to the forgotten. He saw firsthand how generations of culture and collective memory were jeopardized by the gradual collapse of Soviet Russia. With few ways to preserve them, even key moments from his own past had been lost to the march of time.

“Even 30 years ago, I had already lost so much information. Names. Jokes. Phrases. Facts. I can study and re-learn what I have forgotten, but I cannot go back to my school years, my college years, and recollect what I knew. Teachers. Friends. Experiences. In the past 20 years, I have put 75,000 pictures into my photo database. But pictures from before that are lost.” — Stepan Pachikov, founder of Evernote

Pachikov saw computers as a means of not only preserving individual and cultural memories, but also as a way to empower children growing up in the political and social turmoil of Russia in the 1980s. To that end, Pachikov began working with his friend and world-renowned chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov in 1986, and the two men formed the country’s first computer club in Moscow. Pachikov and Kasparov devised a way of encouraging Russian children to develop their handwriting skills under the guise of a simple game. This game ultimately became Paragraph, the world’s first commercial computerized handwriting recognition software.

The results of Pachikov’s educational experiments were mixed, but his work attracted the attention of Apple, Inc., which asked Pachikov to develop his handwriting recognition software for the Newton handheld computer. Pachikov left the frigid temperatures of Moscow for the warmth of Cupertino in Northern California, and made a new home in the United States.

Apple’s Newton project—and, by extension, Paragraph—ultimately failed. Undeterred, Pachikov once again turned his attention to educating children. He embarked on a range of projects in the ’90s, including a cutting-edge virtual reality product that allowed children to learn about history by traveling back through time to the age of the ancient Greeks.

It wasn’t until 2002 that Pachikov began working on what would later become Evernote.

Aside from his lifelong obsession with preserving and expanding human memory, Pachikov’s career has been defined by the ambition of his ideas. Pachikov’s vision of the future has always been a step ahead of the technology of the day. Initially, Pachikov’s vision for Evernote was much closer to the brain-machine interfaces promised by neurotech companies such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink. Pachikov wanted to develop a technology that would serve as an intermediary between man and machine.

However, despite the fantastical nature of Evernote as a concept, the product would have solidly practical applications.

“When you can’t remember somebody’s name, you look stupid. Memory and smartness are integrated. We all have hundreds of thousands of pieces of information, but it’s useless if we can’t find any of it. In business, the worst thing we can say is, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, I forgot your name.’ This is a product I need myself.” — Stepan Pachikov, founder of Evernote

Although Pachikov’s nascent idea shared little in common with Google, both products were grounded in the same basic principle: in the future, knowing how to find information would be far more important than remembering information.

Pachikov worked on the prototype of Evernote (which was initially known as EverNote) for two years, and released a beta version of the tool for Windows in 2004. Pachikov’s decision to target Microsoft’s flagship operating system made sense. In 2002, Microsoft controlled almost 94% of the client-side operating system market. Apple’s OS X, which had been released just a year previously in March 2001, accounted for little more than 2% of the market. Pachikov’s early prototype was a little rough around the edges, but much of the core functionality was there––including the electronic handwriting recognition tech that Pachikov had pioneered at Paragraph.

In 2006, on the other side of the United States in Boston, serial entrepreneur Phil Libin was planning his next move. Like Pachikov, Libin had emigrated from Russia to the United States as a young man. And, like Pachikov, Libin was fascinated by the limitations of human memory. Having launched and sold a successful e-commerce software company and an information technology security firm, Libin was researching the possibilities of augmenting human memory electronically. His third venture, which Libin called Ribbon, would be an organizational tool that would help people save and access the information they needed, when they needed it.

It was then that Libin first heard about Pachikov’s EverNote project.

EverNote and Ribbon were very similar in both form and function. However, Pachikov had made significant headway with EverNote by the time Libin was ready to begin developing his company’s own technology. Libin traveled from Boston to Silicon Valley to meet Pachikov and the two men decided to merge their two fledgling companies rather than compete with one another.

Both Pachikov and Libin were dissatisfied with the limitations of the human mind. However, while both men were idealistic, even philosophic, about their idea, Libin possessed the keen eye for business that Pachikov lacked––a quality that Pachikov believed made Libin an ideal partner.

“[Phil Libin] was smart, educated, and I was completely confident that he would be a much better CEO than I was. His Russian is better than my English. I believed he would transform the company and make it successful.” — Stepan Pachikov, founder of Evernote

Upon the merging of the two companies, Libin set to work. One of Libin’s first tasks was to streamline the various internal projects that Pachikov and his team had been working on, and he insisted that the company focus the entirety of its efforts on refining the idea behind their product: empowering users to capture, search, and store any and all information, wherever they were.

However, Libin’s most significant contribution to the growing company came very early on, when Libin steered Evernote away from Windows towards a bold new frontier––mobile.

The central premise behind Evernote was accessibility. If Evernote was to help people remember everything, then users had to be able to capture everything. That meant mobile. However, in 2006, mobile was far from the dominant platform it is today. Apple’s flagship iPhone wouldn’t be released for another year, and by Libin’s own admission betting big on mobile was exactly that—a gamble.

“From the start, we made a big promise to our users—we would help them remember everything. In order to live up to that, Evernote would need to be easily accessible from every computer, phone or other device that a person used, for the rest of their lives. So, it wasn’t that we predicted the rise of mobile, as much as we felt that mobile would be critical to our success.” — Phil Libin, former CEO of Evernote

That gamble paid off. When the iPhone launched in 2007, Evernote was ready. The product looked and felt completely different from its earlier incarnation. Evernote’s aesthetic was sleek, clean, and stylish, and it felt fantastic to use on mobile.

However, what drove much of Evernote’s initial adoption wasn’t the aesthetic of its mobile app––it was the emergence of the App Store. Just as smartphone apps were a brand-new way of using software, app marketplaces were brand-new, ready-made distribution channels that offered developers immediate access to millions of potential users. Evernote’s engineers worked tirelessly to ensure that Evernote would be available as each new app marketplace launched, each of which expanded Evernote’s footprint considerably.

Libin’s singular focus drove much of Evernote’s initial development. In 2008, Evernote launched in a limited private beta that was aimed squarely at the cult of productivity that had taken root across Silicon Valley.

Libin’s vision for Evernote was a seamless experience that successfully bridged the gap between the physical and digital worlds. To accomplish this, Evernote treated every piece of information—from actual handwritten notes to saved URLs—as a “note,” which are organized into thematic “notebooks.” It’s a clever, familiar convention that Evernote uses to this day. Even early on, Evernote’s functionality was impressive. Users could save all kinds of information within seconds. Digitized handwritten notes, audio recordings, links, pictures taken on a user’s mobile device, saved images, to-do lists, clipped articles—virtually anything users could find online could be saved, archived, and synched across multiple devices.

However, the real brilliance of Evernote was its search functionality, what Libin described as “the electronic version of having something at the tip of your tongue.” Users could search for saved items using an amazing range of search criteria, including date, keyword, topic, location, contacts, or any combination of the above. Users could even download add-ons that allowed notes to be searched by the dominant color of an image. This made it much easier to find saved notes, as users only had to recall a single detail to start a search, much like the way our memories work. This wasn’t just vital to Evernote’s core purpose. It was essential in recreating the rewarding, satisfying feeling of remembering something that would come to define the experience of using Evernote as a product.

“Evernote finds the way your mind works and gives you more and more hooks into your memories.” — Andrew Sinkov, former VP of Marketing for Evernote

This sense of fun and satisfaction was critical in Libin’s view. Evernote’s unique position in the rapidly growing personal productivity space wasn’t lost on the company’s CEO. Evernote faced incumbent competitors at every turn. Box, Dropbox, iCloud, and Google Drive were already dominating online storage. Instapaper offered web clipping tools, as did its main competitor, the now-defunct Spool. Evernote preceded the wave of free online image editing tools that began with the launch of Canva back in 2012, but Evernote’s image-editing tools were far from unique.

To Libin, the experience of using Evernote would be its competitive advantage.

Libin’s product philosophy was responsible for one of Evernote’s few hardware-based flaws—storing data natively on users’ machines and devices. Libin believed that a responsive feel was crucial to the Evernote experience, and that the delay between searching for something and finding something should be infinitesimal. This is the same principle that drove much of Spotify’s early development. Daniel Ek wanted Spotify to feel like users had the entirety of the world’s music right on their hard drives. Libin wanted the Evernote experience to feel similarly responsive, and believed that this would be central to user satisfaction with that experience.

Unfortunately, Libin was fighting a losing battle. As Evernote doubled down on native storage, every other service provider was focusing on the cloud. Although this decision didn’t create any existential problems for Evernote in 2008, it was the first sign that Evernote was diverging from the broader trends in tech that would cause the company so many headaches later on.

Evernote launched as a freemium product. This was vitally important to Libin. He believed that Evernote would become increasingly valuable to users the longer they used the product and the more they captured and stored within it. As such, Libin wanted to make Evernote as sticky as possible—and he did so by making the free version of the product incredibly generous. There were virtually no feature restrictions or other incentives for users to upgrade from free to paid plans. In fact, the only benefit of upgrading to a paid, $5-per-month subscription was additional storage space.

“I don’t need to squeeze money out of you. I’ll have the rest of your life to take your money. It’s my long-term greedy strategy. Our slogan is, ‘We’d rather you stay than pay.'” — Phil Libin, former CEO of Evernote

Libin’s attitudes toward freemium software may have been popular with Evernote’s growing userbase, but it was repellent to investors. One VC after another turned Libin’s company down. There were no complaints about the product—far from it—but there just wasn’t enough incentive for free users to upgrade to paid plans.

After struggling to secure institutional investment, Evernote entered into an agreement with a European VC that would have seen the company receive $10M in funding. On the morning in October 2008 when the two parties were due to meet to sign the papers, the investor canceled the meeting and pulled the offer of funding. With just three weeks’ worth of cash at hand, Libin came to the grim realization that Evernote as a company would not survive. With little money and fewer prospects, Libin agonized about how he would break the news to his team and employees.

It was around that time that Libin received an email from a Swedish user who loved Evernote. The user, whose identity remains a secret to this day, told Libin that Evernote had made him happier and more productive. However, the Swedish user didn’t want to just tell Libin how much they loved the app—they wanted to invest. Libin admitted that the company was in need of funding, at which point the mysterious Swedish Evernote evangelist offered to front the company $500,000.

Evernote was saved.

“He was just a computer nerd and entrepreneur. He had some money and fell in love with our product, simple as that. It was just good luck. Had I gone to bed ten minutes earlier, I wouldn’t have opened his email right away and probably gone into work and closed the business.” — Phil Libin, former CEO of Evernote

Evernote’s anonymous benefactor didn’t just save the company, they opened the door to the kind of institutional investment Evernote had been chasing before the global economy tanked. Evernote kicked off a series of funding rounds over the next two years that propelled the company to new heights of growth. The company started by raising $26M as part of its Series A round led by DoCoMo Capital in September 2009. Two months later in November 2009, Evernote raised another $10M as part of its Series B round led by Morgenthaler Ventures and Sequoia Capital. Just under a year later in October 2010, Evernote raised another $20M as part of its Series C round, again led by Sequoia, as well as another $50M as part of a venture round led by Sequoia in July 2011.

Evernote had gone from venture capital pariah to Silicon Valley darling in less than three years, raising a total of more than $100M in the process.

Libin’s company took full advantage of its sudden reversal of fortunes, using much of its new funding to expand its engineering teams and expand beyond the company’s headquarters in Redwood City, California. One thing Evernote didn’t spend a cent of its newfound fortune on, however, was advertising.

Since launching in private beta in 2008, Evernote’s growth had been gradual, steady, and entirely organic. The product had more than 125,000 users before Evernote emerged from its closed beta, thanks in part to an article on TechCrunch that drove several thousand sign-ups.

During the closed beta, Evernote was invite-only. However, while many products use invites as a marketing strategy to capitalize on exclusivity of access, Evernote did so out of an abundance of caution. Between the technical overhead of synchronizing native applications across multiple platforms in real time and working with a new type of backend server architecture, Libin’s engineers were more concerned with the stability of their systems than manufacturing hype.

“The fact that you have to sign up and send around invites to get in actually generated some buzz. That was never our intention; we never thought of the closed beta as a marketing exercise. We were frankly terrified that everything would crash all the time.” — Phil Libin, former CEO of Evernote

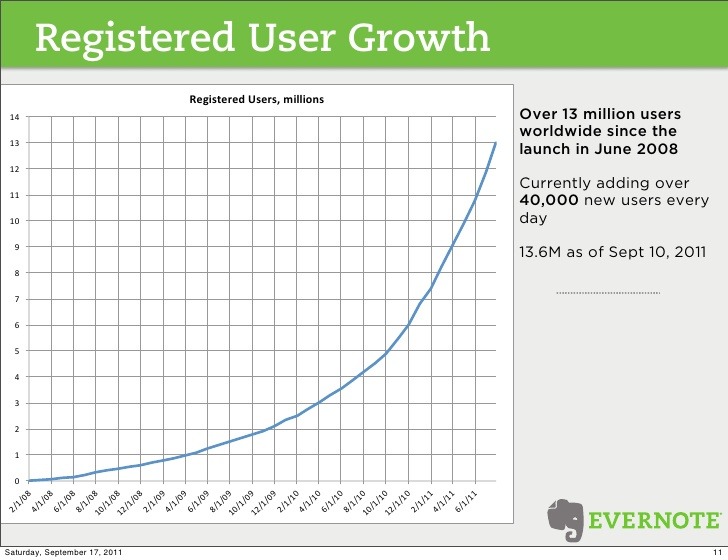

Evernote’s freemium model may have been a dislike for investors, but Libin’s instincts about slow-burn, long-term growth had been proven right. In early 2011, just three years after launching, Evernote became profitable. Evernote had 80 employees, more than 10M users, and annual sales of approximately $16M.

Having been dangerously close to the brink of disaster, Evernote had emerged from the global financial crisis not only unscathed, but flush with VC cash. The company had achieved profitability in just three years, and the future looked bright for Evernote––until the company began to lose its way in 2011 with a series of failed product launches that jeopardized everything the company had built.

2011-2015: New Products, New Markets, New Problems

Evernote began the period from 2011 to 2015 in an incredibly strong position. Evernote was already profitable and had more money in the bank than it knew what to do with. The company was growing steadily, hiring new talent and expanding into new locations. And, most importantly, the product was attracting upward of a million new users every month. However, the honeymoon period didn’t last. In an attempt to diversify its revenue streams, the company embarked upon a series of disastrous product launches that confused users and investors alike—all of which took the company farther and farther away from the core vision of its founders.

In the summer of 2011, Evernote released the first of three standalone products it would launch over the next six months: Evernote Peek. The first Smart Cover app for Apple’s newly released iPad 2, Peek was a simple trivia application that leveraged the responsive wake and sleep function of the iPad’s Smart Cover feature. Users could lift part of their iPad’s Smart Cover to see a trivia question on-screen. To reveal the answer, all they had to do was lift up the rest of the cover. Users could use either Peek’s questions or their own answers as the basis of Notebooks within the main Evernote app, but Peek offered users little real utility besides a momentary distraction.

A few months later in December 2011, Evernote released two more standalone apps for iOS: Evernote Food and Evernote Hello. Essentially a simplified, specialized version of the main Evernote app, Evernote Food allowed users to record and log their meals in digital notebooks in much the same way the main Evernote app allowed them to capture and store everything else. Users could organize their culinary memories by tagging locations and other people, making it easier for users to remember what they ate, with whom, and where. The only real differences between Food and the main Evernote app were the integrations with Facebook and Twitter. Customers could use these integrations to share details of their last amazing meal with their networks, and some food-specific navigational elements.

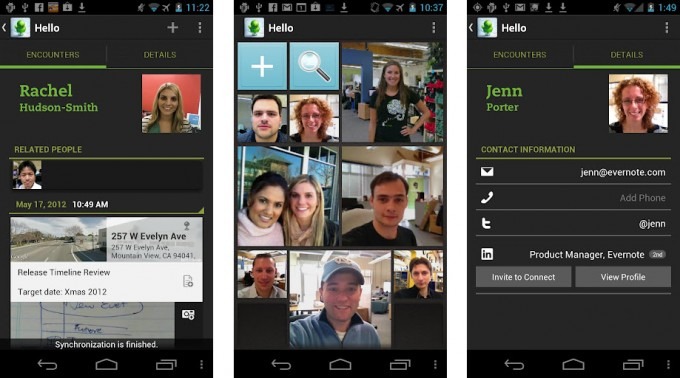

Evernote Hello was an even stranger app than Evernote Food. The purpose of Hello was ostensibly to make it easier for users to remember people. Users could create contact listings within Hello in a similar way as adding a new contact in their phone. However, what made Hello such a bizarre—and ultimately damaging—product was the fact that everything in Evernote Hello had to be done manually. The app did not support near-field communication (NFC), the communication protocol that powers contactless payment systems such as Apple Pay and allows mobile devices to exchange small amounts of data. Hello didn’t even have a rudimentary electronic business card reader. Every field had to be completed by hand.

Users and investors alike were completely baffled by Food and Hello. Firstly, the main Evernote app could already do everything Evernote Food could do and more. There was no incentive whatsoever for people to use Food over the main Evernote app. Secondly, the lack of NFC or e-card support for Hello was an unforgivable sin for a contact manager product. Asking either users themselves or their new acquaintances to enter contact details manually was an immense barrier for the product to overcome and one with virtually no payoff for users.

It isn’t hard to see the reasoning behind the two products.

Food selfies wouldn’t become the pop-cultural staple they are today for several years, but many people were already enthusiastically photographing their food and sharing it on social media by 2011. Evernote Food was a transparent attempt by Evernote to become the primary destination for food photography, a position dominated by Flickr at that time.

Although it may not have seemed like it at the time, Evernote Hello aligned strongly with Pachikov’s original vision to help users remember everything. Pachikov himself often used forgetting people’s names in professional settings as a prime example of how Evernote could be an indispensable part of people’s everyday lives. What Hello got wrong, however, was the execution. If Hello had shipped with NFC support, it could have potentially opened up Evernote’s products to an entirely new market of business users. It had to be effortless to work. As it stood, Evernote Hello was virtually useless and accomplished little besides diluting the Evernote brand.

Evernote’s increasing range of products was confusing, but didn’t dissuade investors. In May 2012, Evernote officially earned “unicorn” status—a valuation of $1B or more—after raising $70M as part of its Series D round led by CBC Capital.

Evernote didn’t need to raise any more funding. The company still had much of the $96M it had raised to date, but the company planned to use its latest round to expand further into the Chinese market. Unlike most Western tech companies, whose products are often quickly copied and rebranded by Chinese firms, Evernote decided to create its own clone for the Chinese market, Yinxiang Biji, or “memory notebook.” This would ultimately prove to be a smart play, and China would later become Evernote’s second largest market outside the United States.

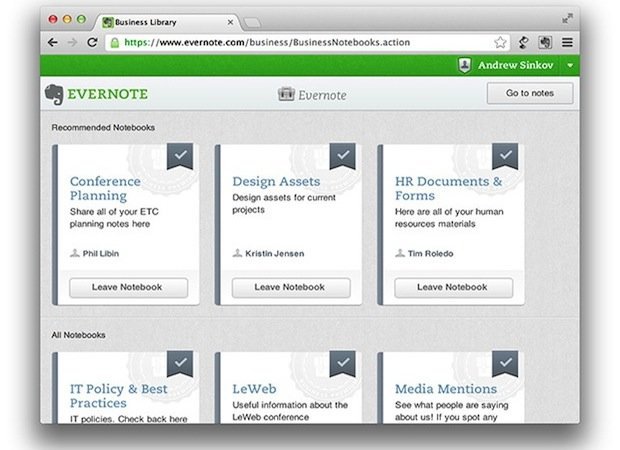

After a series of worrisome decisions and bewildering product launches, Evernote attempted to course-correct in August 2012 with the launch of Evernote Business.

This was a logical, if predictable, move for the company. By the time Evernote Business launched, Evernote was wildly popular. The company had around 230 employees worldwide, tripled the number of developers working with Evernote’s API, and more than trippled its userbase from 12M to more than 38M in just one year.

Having accepted almost $100M in venture funding, Evernote was under considerable pressure to diversify its revenue streams and pursue business users more aggressively. Professional users could connect their business account to their personal account effortlessly. This encouraged business users to bring Evernote to work with them, in much the same way Slack had done in its early growth stage. To sweeten the deal, users who connected personal accounts to business accounts had their basic freemium accounts upgraded to Evernote Premium.

The pressure to go after business users intensified further in November 2012, when Evernote raised an additional $85M as part of its secondary market round led by British venture fund M8 Capital. This brought Evernote’s total venture funding to more than $250M and a valuation of $2B.

Evernote’s next major product launch came almost a year later in September 2013. However, this product wasn’t another specialized version of the Evernote app, it was an extensive range of physical Evernote-branded products that the company would sell via its new Evernote Market.

In the space of a few short years, Evernote had achieved profitability, had millions of dollars in the bank, and the company was growing fast.

Evernote Market squandered almost all of the company’s brand equity for nothing.

“If you make different products and they’re great, people are like, ‘That’s genius! Clearly, the right thing to do.’ And if you focus on one product and it fails, people are like, ‘That company is no longer capable of innovating.'” — Phil Libin, former CEO of Evernote

It’s hard to understate the damage that the branded products sold through the Evernote Market inflicted on the Evernote brand. It made absolutely no sense. Users didn’t want Evernote-branded tablet styluses or Evernote Moleskine notebooks or Evernote backpacks. They wanted an organizational and productivity product that worked.

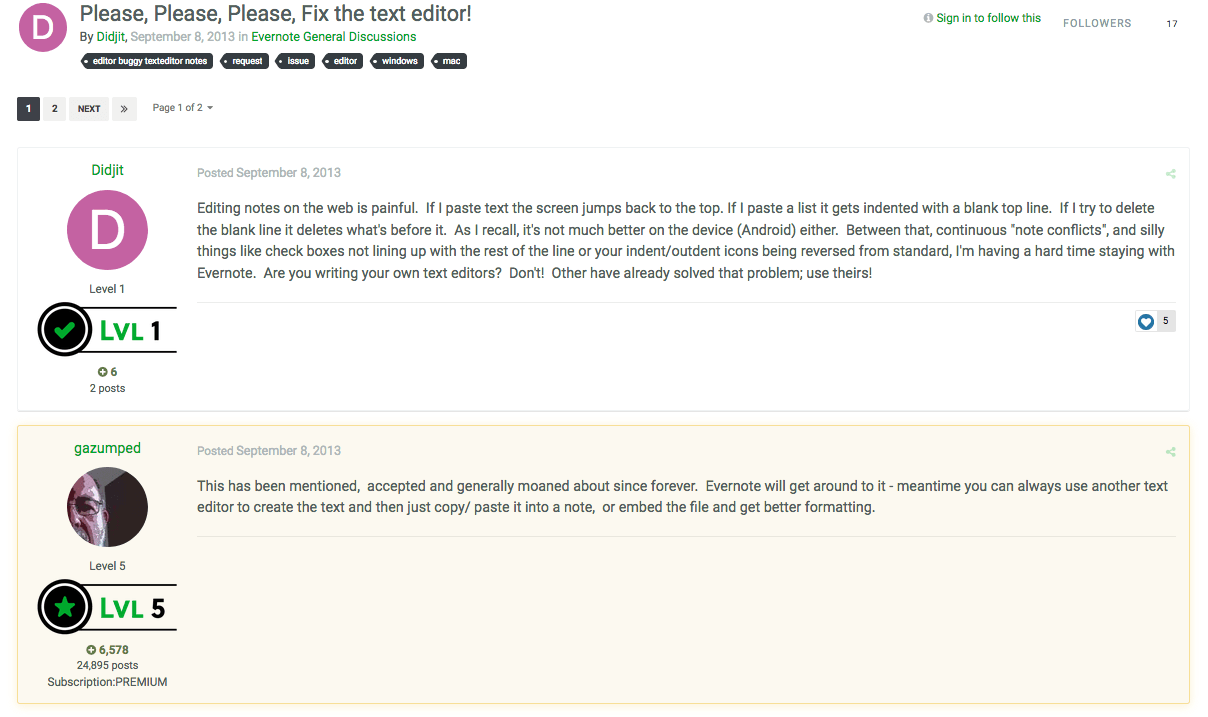

The fact that the 2013 version of Evernote was widely considered the buggiest, most unstable version the company had released at that point added insult to injury.

Rather than fixing the software problems that users actually cared about, Evernote started selling branded backpacks instead.

Evernote Market wasn’t just a troubling sign that the company—and Phil Libin himself—had begun to lose its way. It was another major step away from Pachikov’s vision of what Evernote could be.

Both Pachikov and Libin shared a desire to create a “100-year company,” but Evernote Market did nothing to work toward or advance Pachikov’s vision of Evernote as an extension of the human mind. Pachikov’s vision was bold, ambitious, and transformative. By comparison, Evernote Market felt like a cheap cash grab.

The company’s fortunes went from bad to worse in 2014.

Despite its popularity, Evernote had developed a reputation among its growing userbase for being a buggy, unstable product. For the most part, such grumbling was largely restricted to complaints on the product’s official forums and the occasional rant on social media.

That changed when Jason Kincaid, a former TechCrunch writer, published a post on his personal blog titled “Evernote, the bug-ridden elephant.”

Kincaid had been an Evernote power user for years, having captured almost 7,000 notes since discovering the product. The post was a reluctant but scathing take-down of Evernote’s notorious instability, which Kincaid felt compelled to write after experiencing a slew of technical problems including corrupted files, incomplete backups, and a poor response from Evernote’s customer support team. The post went viral and garnered so much attention that Libin personally contacted Kincaid to apologize.

“None of this has been life-shattering, but given how reliant I am on Evernote, it is deeply unnerving—now each note I instinctively leave myself is tinged with anxiety. I’m concerned that as I dig through my Evernote archive, I’ll encounter more corrupted audio notes, and, worse, my paranoia is increasingly convinced that there may have been notes that never were saved to the archive at all.” — Jason Kincaid

A little more than a year later in October 2014, Evernote unveiled its latest product, Work Chat. A simple messaging client, Work Chat was designed to complement Evernote’s Business plans.

It was also long overdue. Team-based collaboration had been an enormous blind spot in Evernote’s vision for years. The company had already missed one major consumer tech trend by ignoring the exodus of products and services migrating to the cloud and insisting on developing Evernote as a native app.

Similarly, Evernote had been designed as an organizational tool for individuals, when virtually every other productivity tool on the market emphasized team-based collaboration. Work Chat was the first small step toward solving this urgent problem.

Unfortunately for Evernote, that ship had sailed.

As a whole, the company had been distracted by chasing the wrong revenue streams. Instead of building a solid team-based product, Evernote built a food app. The company had expanded too quickly in the wrong direction.

Everything besides the main Evernote app was a distraction from the company’s core mission to help people remember everything. Products like Slack and Google’s G Suite had successfully made the leap from personal product to collaborative product, whereas Evernote had not.

Aside from raising an additional $20M as part of its Series E round in November 2014, Evernote kept a low profile for the next year or so until July 2015, when the company introduced major changes to its pricing. Under the new structure, Evernote’s Premium plans increased from $45 to $50 per year. The other major change to the product’s pricing was the introduction of a new, middle-tier option called Evernote Plus, which cost $25 per year.

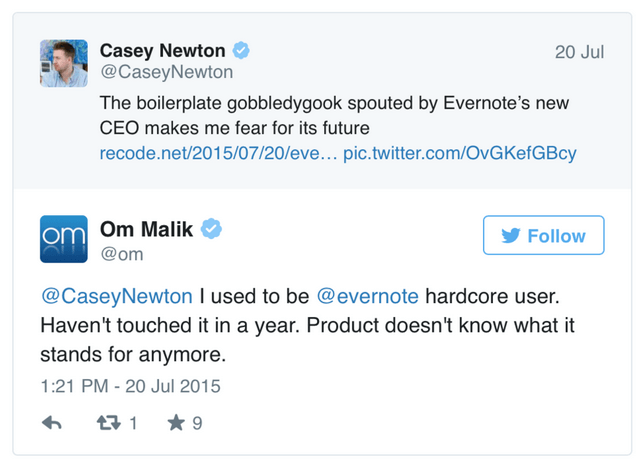

Evernote changed more than just its pricing structure in 2015, it also changed the company’s leadership. In July 2015, Libin announced that he would be stepping down as Evernote’s CEO and handing the reins to former Google Glass executive, Chris O’Neill, as his successor.

The disastrous launch of Evernote Market, the instability and bugginess of the product, the lack of a clear direction for the company—they had all taken their toll on Evernote as a company, and Libin as Chief Executive in particular. Apparently discouraged by Evernote’s failure to capitalize on its earlier success, Libin reportedly showed little interest in the business side of the company. He described himself as “not passionate” in the announcement about O’Neill’s appointment, an admission as frank as it was surprising.

“Attracting and retaining talent is a core responsibility of the CEO, and if Libin is seriously disinterested in the latter, he should have departed long ago. I can’t imagine the feeling of being an Evernote employee who hears your long-time CEO (and still executive chairman) publicly admit to not giving a shit about your future.” — Josh Dickson, founder of Syrah

Libin wasn’t the only one who saw the writing on the wall. As news of O’Neill’s position as Evernote’s new CEO spread, many people expressed doubts about O’Neill’s suitability and experience––not to mention the product’s ongoing identity crisis.

Libin’s failure to hire a COO until June 2015, when the company promoted Linda Kozlowski from VP of Worldwide Operations, was seen as yet another symptom of the company’s leadership problems.

From 2011 to 2015, it seemed as though Evernote took two steps backward with each step forward. The company had continued to invest in the development of new products, but none of these products expanded or built upon Evernote’s core functionality or purpose. With each new experiment and failed product, Evernote drifted farther and farther away from Pachikov’s vision—an identity crisis from which Evernote never really recovered.

2015-Present: Returning to Evernote’s Roots

For Evernote, the period from 2015 until the present day can be summed up in four short words: too little, too late. Evernote’s various failed experiments to diversify its products and revenue streams hadn’t just wasted millions of dollars—it wasted precious time the company didn’t have. Moving away from the core value proposition of the Evernote product had been a huge mistake. The only thing that could save Evernote was returning to the product’s roots. For O’Neill, this meant getting back to Pachikov’s original vision for Evernote as an extension of the human mind. Unfortunately for the company, it never managed.

One of O’Neill’s first tasks as CEO was to get Evernote’s house in order. This began with the prompt closure of Evernote Food in August 2015. Evernote Food had been relatively popular, but ultimately, it wasn’t worth the time and resources necessary to maintain it—especially considering the primary Evernote app could already do virtually everything Food could do.

Around six months later, the company announced it was also closing the Evernote Market. According to Evernote, the company had sold approximately $12M worth of branded goods through the Evernote Market. Even if sales figures had been higher, the Evernote Market had done considerable damage to the Evernote brand. Closing it was both long overdue and urgently necessary if the company was to regain its users and investors’ trust.

A little more than two months after Evernote shuttered its Market, the company lost the first of many executives it would lose over the coming years. Dave Engberg, the company’s founding CTO, left the organization after almost nine years. Like many other Evernote execs who departed the company around the same time, Engberg’s departure was decidedly low-key.

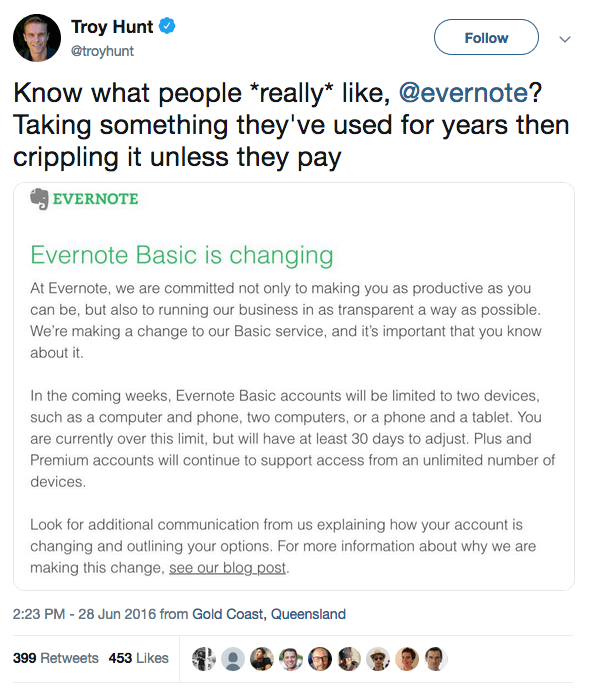

Shortly after Engberg’s exit, Evernote introduced sweeping changes to the product’s pricing. First, serious restrictions were introduced to Evernote’s free plans. Free users were limited to synching their Evernote data across just two devices. Second, Evernote raised the price of its Plus and Premium tiers to $34.99 and $69.99 per year respectively, a price increase of roughly 40%.

One of the biggest and most unpopular changes to Evernote, however, wasn’t its new pricing. It was the 60MB upload limit applied to Evernote’s free plans. For customers who used Evernote to upload primarily text-based notes, the new restriction may have felt less punitive.

For users who relied on Evernote to save images and other media files, however, the new upload cap was brutal.

“Our goal is to continue improving Evernote for the long term, investing in our core products to make them more powerful and intuitive while also delivering often-requested new features. But that requires a significant investment of energy, time and money.” — Chris O’Neill, CEO of Evernote

For Evernote, the restructuring of its freemium product was both long overdue and urgently necessary. For Evernote’s users, however, it was a slap in the face. Not only had Evernote crippled its free version, severely limiting its utility to free users, it had also failed to fix many of the bugs that still plagued even paid versions of the product.

To be fair to Evernote, the company had little choice but to increase prices. Years of Evernote’s extremely permissible freemium product had spoiled users who had grown accustomed to making use of Evernote for free and had harmed the company’s revenue growth. What the company should have done to monetize the product while aligning with customers would have been to gradually introduce restriction incentives to its free version over time, rather than transitioning from a generous freemium product to a comparatively expensive paid service.

Pricing changes are some of the most impactful things a company can do. Evernote didn’t put enough thought into its pricing over the years, which is why their once loyal userbase wasted little time in criticizing them over the new pricing plan.

The company’s primary competitors—Microsoft’s OneNote and Apple’s Notes—weren’t as fully featured as Evernote, but they offered a lot more functionality free of charge, making Evernote’s new pricing even less appealing.

The next major change to Evernote under O’Neill’s leadership came a few months after the product’s pricing restructure when the company announced it was migrating from Evernote’s own proprietary data infrastructure to Google Cloud. This was no small feat.

At the time, Evernote had approximately 3.5 petabytes––or 3.5 million GB––of data on its 200 million users. Evernote could have opted to use Amazon Web Services or Microsoft’s Azure infrastructure to host its data. The company reportedly chose Google as its cloud provider due to the potential applications of Google’s machine-learning technology. Despite the costs and sheer amount of work involved in the migration, the decision could have been seen as another small step toward Evernote becoming the company Stepan Pachikov envisioned all those years before. Evernote had long been rumored to be developing voice recognition and translation features to the product to make capturing information even easier. This made Google’s Cloud Machine Learning Engine the ideal choice for intelligent, responsive features such as voice recognition.

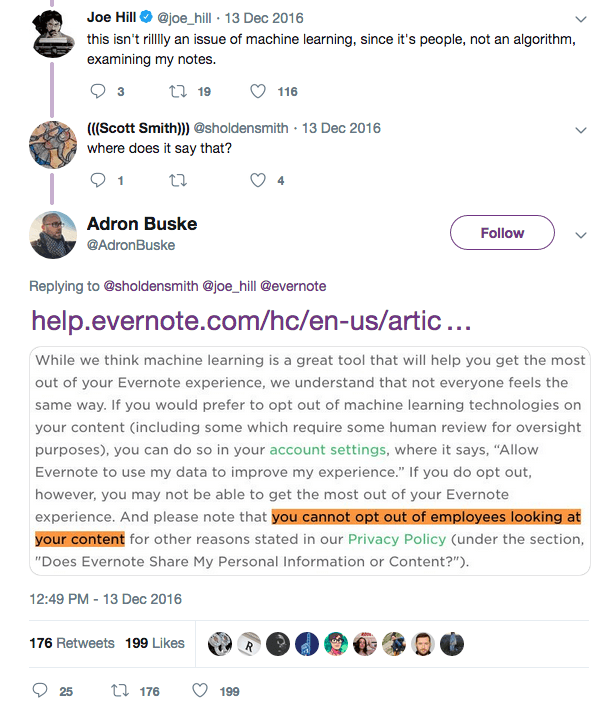

Data security had been a thorny problem at Evernote for some time. Roughly 50 million user accounts were compromised following a security breach in 2013, and Evernote’s decision to migrate its data infrastructure to Google Cloud was seen as a smart move for a company with so much data and so many users. However, the company suffered another PR black eye when TechCrunch reported that the company’s new privacy policy allowed Evernote employees to read users’ private notes.

“The latest update to the Privacy Policy allows some Evernote employees to exercise oversight of machine learning technologies applied to account content. While our computer systems do a pretty good job, sometimes a limited amount of human review is simply unavoidable in order to make sure everything is working exactly as it should.”

The policy was framed as a way for Evernote to ensure the accuracy of its machine-learning technologies. What users took exception to was how the policy was structured. Despite the company’s attempts to backtrack later, the original update to Evernote’s privacy policy clearly stated that users could not opt out of Evernote employees examining their notes.

The backlash was powerful and immediate. Many users took to Twitter to point out the intrusive nature of the policy, and many agreed that the company’s response had been tepid and frustratingly vague.

In February 2017, O’Neill confirmed that after several difficult years, Evernote was cash-flow positive. This might not have been as warmly welcomed as an announcement that the company was once again profitable, but it was an important step for the beleaguered company.

Evernote kept a relatively low profile following the machine-learning privacy debacle. A year or so later, in February 2018, Evernote took another important step forward with the launch of Evernote Spaces, the company’s first truly collaborative team-based product.

Spaces’ biggest problem wasn’t the product itself––it was the fact that Spaces was released about six years too late. Evernote should have developed Spaces back in 2012, rather than wasting time, money, and brand equity with Evernote Market.

By the time Spaces was released, the team-based productivity market was already saturated with far superior products, including Slack for real-time communication, Box and Google Drive for online storage, and G Suite for personal and team-based collaboration. There was simply no need for Evernote Spaces.

Even more ironic was the rationale behind the development of Spaces. In an interview, O’Neill claimed that 70% of Evernote users were using the product in their personal lives and at work. Had Evernote developed Spaces sooner, it could have leveraged the significant overlap between individual and business use-cases to make greater headway into the productivity tools market.

As Evernote sought to get back to its roots as a product that would help users remember everything, the brand underwent a significant overhaul in August 2018. Evernote was in dire need of a clean start, and a major rebrand would embody the company’s new sense of purpose.

![]()

Evernote’s new branding was fresh, but it did little to solve the company’s underlying problems.

The next month in September, TechCrunch reported that Evernote had lost the majority of its ranking executives within the past month alone, including CFO Vincent Toolan, CPO Erik Wrobel, CTO Anirban Kundu, and Head of HR Michelle Wagner. These departures didn’t just broadcast to the world that Evernote was a company in trouble. They were symptomatic of a company that had completely lost its way.

Evernote didn’t know what it should be, only what it shouldn’t be. The company had bet big and won by being on as many devices as possible, but had ignored product reliability. Evernote wasn’t able to keep up with consumer expectations which led the company to expand too rapidly in the wrong directions and, ultimately, it was left behind by newer entrants in the market.

O’Neill’s efforts to right the ship after taking the helm were admirable and badly needed, but it’s painfully clear that Evernote will probably never be the extension of the human mind that Stepan Pachikov first imagined all those years ago.

The only question now is how Evernote’s story will end and how the company will be remembered.

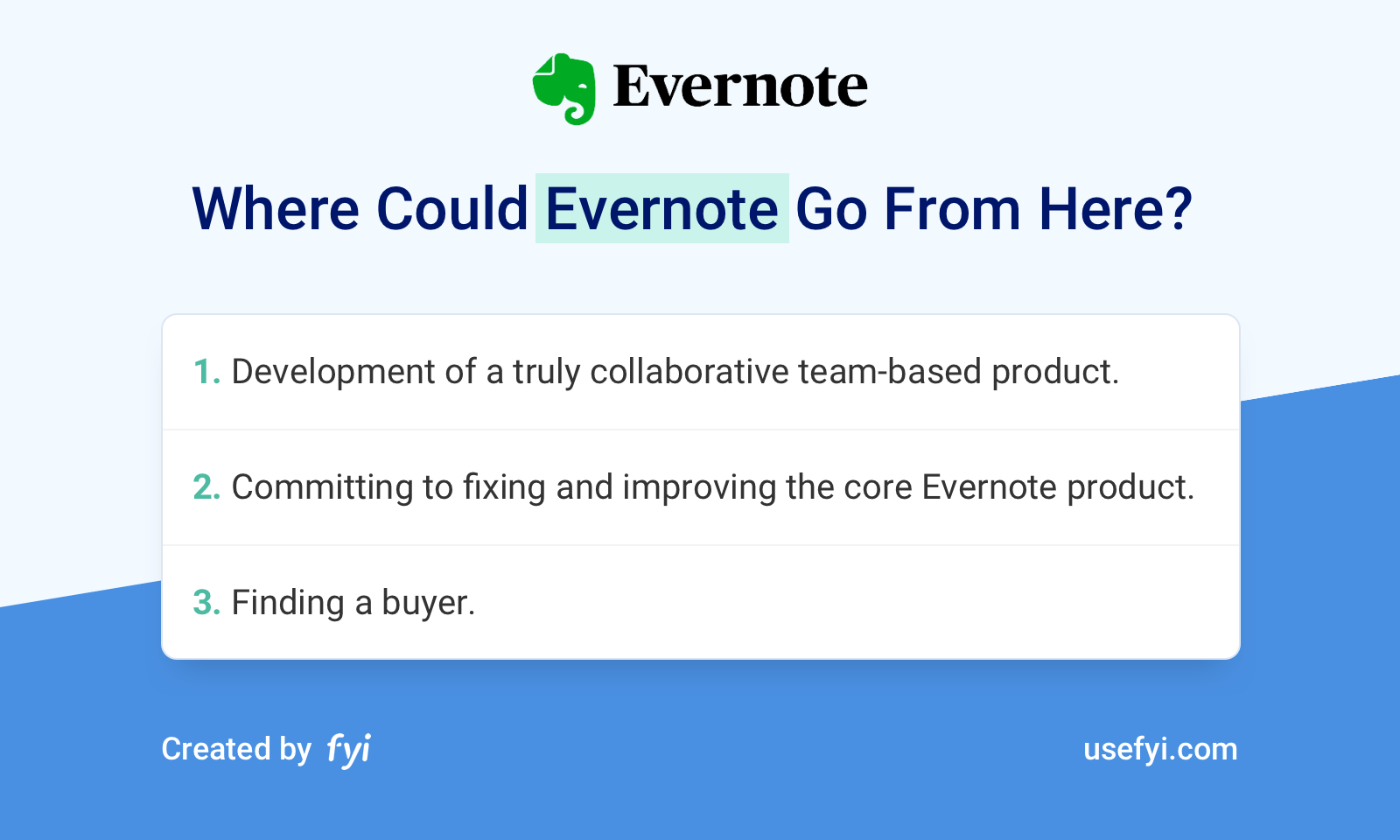

Where Could Evernote Go From Here?

Despite the problems that have besieged the company and product for years, Evernote still has a relatively large user base. Where could Evernote go from here?

- Development of a truly collaborative team-based product. The most optimistic step that Evernote might take is to double-down on development of Spaces or another team-based collaborative product. Evernote may have won its big bet on mobile in 2006, but it missed the boat on cloud-based collaboration, which profoundly reshaped the personal and professional productivity spaces. If Evernote hopes to survive and become the 100-year company that Phil Libin always thought Evernote could be, it will need to develop a strong, team-based product that can compete with G Suite and similar tools.

- Committing to fixing and improving the core Evernote product. Evernote’s reputation for bugs and instability is well-deserved. The company neglected critical technical flaws for years, and users took note. Just as Evernote must develop a team-based tool if it hopes to survive, the company will also have to take its legacy technical issues seriously if the company wants to win back the hearts and minds of formerly enthusiastic users.

- Finding a buyer. Evernote’s fall from grace should be a cautionary tale for any aspiring founder or entrepreneur. At this time, one of Evernote’s few remaining options is to hope that a buyer will acquire the company. Evernote is nowhere near ready to IPO, and while the company is likely to sell for much less than anyone would like, an acquisition would be an ideal end-game for the beleaguered company.

What Can We Learn from Evernote?

As sad as it is, Evernote’s story offers plenty of lessons to entrepreneurs hoping to launch similarly ambitious products. What can we learn from Evernote?

1. Timing is everything even if it’s accidental. By Phil Libin’s own admission, Evernote’s timing was crucial to the company’s success. Had Evernote’s development schedule been even six months off, it would have missed the huge growth driven by its status as a launch application when the iPhone was released in 2007. Evernote’s timing may have been at least partially accidental, but it played an outsized role in the company’s growth trajectory.

Consider your own product:

- Let’s say you have a chance to travel back through time to one year before your product’s launch. What, if anything, would you have done differently? How could you capitalize upon external trends or developments to drive initial growth, as Evernote did?

- Would timing the release of your product have an impact on initial adoption? Put another way, is there anything you could do (or have done) to time your product’s launch to make a bigger impact?

- What’s the “tailwind” at your back? Aside from your own hard work, what tailwinds will push your product forward?

2. Stay true to your convictions even in the face of overwhelming opposition. Phil Libin was criticized for years for giving so much away in Evernote’s freemium product. Contrary to conventional wisdom, Libin was right to be so protective of Evernote’s freemium version. Evernote is a classic—if not the classic—freemium product, and Libin was right to insist on maintaining the free version’s features as long as he did, because it drove growth and encouraged users to become heavily invested in Evernote as a product.

Think about your product’s journey thus far:

- Can you recall a time in which you compromised on a product or business decision that you later came to regret? If so, why did you give in? Did you or your product gain anything by doing so, and conversely, would you have gained anything if you had resisted that pressure?

- How well does your actual product align with your original vision for the product? Is it true to your vision, or have you lost sight of what your product should be?

- Libin’s leadership was widely criticized over the years, but he did an excellent job of framing Evernote as a freemium company, especially when dealing with investors. How have you evangelized or advocated for the decisions you’ve made for your product?

3. Pay close attention to broader trends even if they don’t affect you right now. Evernote bet big—and won—on mobile. Evernote missed out on an immense opportunity by failing to respond to the ongoing evolution of consumer tech and opting to double-down on Evernote as a product for individuals, not teams. This arguably set the company up to fail later on, as there was no way for Evernote to course-correct in time to fend off emerging competitors that capitalized on the team-based collaboration trend.

Consider your product and its place in the broader tech ecosystem:

- What’s the single most important trend in tech facing your product and why?

- Similarly, what broader technological development poses the greatest risk to your product? How have you mitigated this threat, and could your product move quickly enough in response?

- How are you innovating on your original vision? Could you go after different segments of your primary market?

Elephants Never Forget

They say that elephants never forget, and Silicon Valley is no different. Despite its potential and the boldness of vision of the company’s founder, Evernote ultimately lost sight of that vision. By the time it realized this, it was too late.

Despite still having a loyal base of hardcore users, Evernote’s future is far from certain. Whether the company can dig itself out of its current predicament remains to be seen, but there’s little doubt that Evernote will not be remembered kindly.

Do you use Evernote? You can find your Evernote documents, alongside documents from other apps, in 3 clicks or less by using FYI.