Dropbox Paper: Paper Tiger, or King of the Jungle?

On April 17, 2014, cloud-storage provider Dropbox announced it had acquired two companies. The first was photo-sharing service Loom. The second was collaborative document-editing tool Hackpad.

Originally forked from the open-source Etherpad, Hackpad was a popular tool with a loyal following. As well as being a capable, lightweight document tool, Hackpad was also very popular as a wiki tool. It was even used to create the wiki for SXSW in 2012. Hackpad boasted several features that were unique at that time, such as syntax highlighting for HTML, CSS, JavaScript, SQL, and other programming and markup languages.

Unlike most acquisitions, Hackpad lived on for three years after Dropbox bought it. After that point, Hackpad became Dropbox Paper.

Dropbox’s acquisition of Hackpad and its rebrand to Dropbox Paper was a pivotal moment for the cloud-storage provider. Despite achieving strong user and revenue growth, Dropbox had to diversify beyond its core storage business if it hoped to continue growing. Google had already made bold steps in the document-editing space with Google Docs. Even so, Dropbox sensed an opportunity with Hackpad. An opportunity the company wasted little time capitalizing upon.

Here are the key strategic decisions that explain where Dropbox Paper is today:

- Why Dropbox had to diversify its core business beyond storage and why acquiring a document-editing tool was such a smart strategy

- How increasing competition in the collaborative productivity space influenced Paper’s development

- Why failing to integrate Paper into the new Dropbox was a missed opportunity and raised questions about the company’s vision for the product

By 2014, interest in and demand for collaborative cloud-based document software was intensifying. Google was making bold moves into the space with G Suite. Predating Google Drive by four years, Dropbox had already achieved impressive growth in the cloud-storage space by the time Google decided to get in on the action. However, even as a new player in the space, Google cast a long shadow. Dropbox couldn’t afford to sit back and allow Google to encroach on the market share it had built since 2008. So, Dropbox did what many companies facing an emergent competitor do.

Dropbox went shopping.

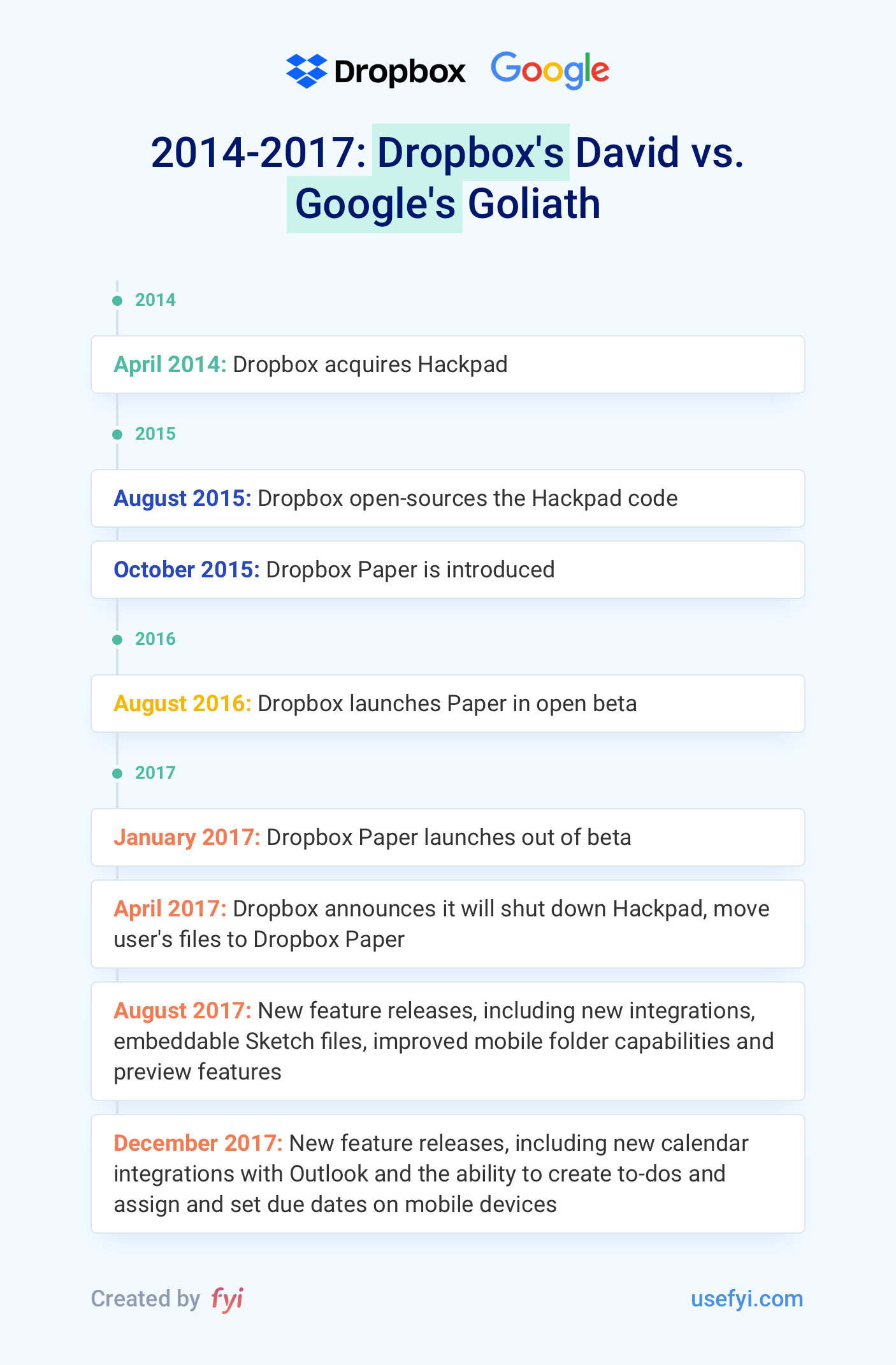

2014-2017: Dropbox’s David vs. Google’s Goliath

By the time Dropbox acquired Hackpad in 2014, things were heating up in the cloud-storage space.

Dropbox had more than 300 million users worldwide.

Microsoft’s OneDrive wasn’t far behind, with more than 250 million users.

Google Drive was nipping at Microsoft’s heels with 240 million users.

Cloud storage had become big business.

However, aside from some relatively minor differences in storage allowances, there was very little to distinguish one service from another. All three of the major players in the cloud-storage space were competing for the same users. This was especially true in the enterprise, which all three companies had been targeting aggressively.

Dropbox may have been ahead of Google and Microsoft by 50 million users or so, but this didn’t mean Dropbox could afford to take its foot off the gas. If Dropbox hoped to continue its growth trajectory, it had to diversify beyond storage.

In 2008, Dropbox’s core value proposition of using the cloud to make it effortless to sync and share files across computers was unique. By 2014, this was hardly the case. If Dropbox wanted to be anything other than a commoditized storage provider, it had to expand its offerings.

Dropbox went on an acquisition spree in 2014.

In March, the company bought work-chat platform Zulip for an undisclosed sum. Around two weeks later, Dropbox announced it had acquired German social-reading service Readmill for approximately $8 million. Next, Dropbox acquired photo-sharing service Loom just days after announcing Carousel, Dropbox’s Flickr-like photo-storage service. And in April 2014, Dropbox acquired Hackpad.

Launched in 2011, Hackpad was developed by Igor Kofman and Alex Graveley. Hackpad was forked from the open-source Etherpad. Hackpad boasted several forward-thinking features that would later become standardized across the collaborative productivity space, such as Hackpad’s use of the “@” shortcut to tag other users and create new documents.

Some members of the open-source community were upset that Kofman and Graveley had forked an open-source project to develop proprietary software. Despite this, many people loved Hackpad.

One of the most popular aspects of Hackpad was the tool’s simplicity. Google Docs may have offered more bells and whistles. But Hackpad felt like a true collaboration tool, whereas Google Docs felt like an online word processor.

It may have appeared that Dropbox was buying companies left and right with little clear direction in mind. However, in hindsight, Dropbox’s many acquisitions in 2014 all helped set the stage for what became Dropbox Paper. Zulip may have been a Slack clone, but it also boasted some cool features that had potential in a document-editing tool, including threaded replies. Readmill might not have seemed like the most logical acquisition for Dropbox but it’s highlighting and sharing features also had potential applications in a document tool.

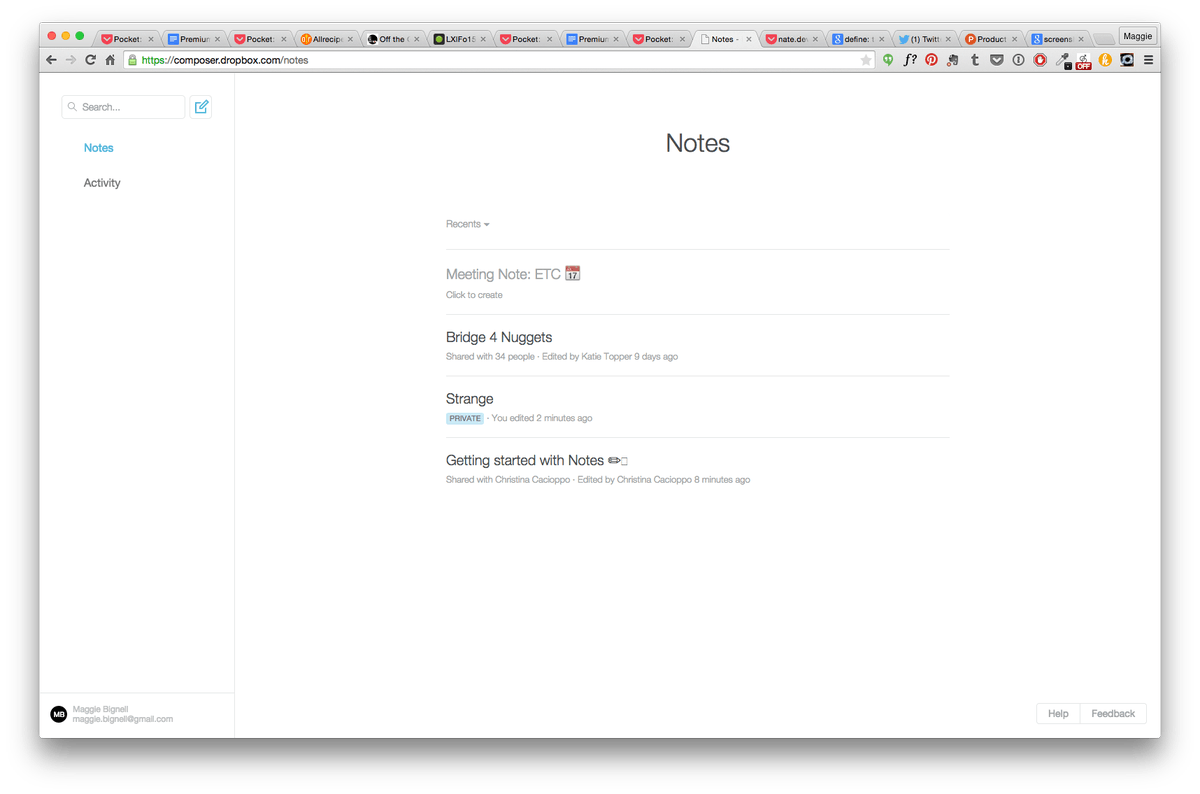

In April 2015, Dropbox began testing an online note-taking service called “Project Composer.” An eagle-eyed Product Hunter spotted Composer first, and it didn’t take long for people to notice the similarities between Composer and Hackpad, especially after some early users found that they could access their Hackpad notes directly from Composer.

Composer didn’t retain its original name for long. Composer was renamed Dropbox Notes shortly after Composer was first discovered.

Dropbox Notes looked a lot like what Dropbox Paper looks today. It boasted a clean, minimalistic UI featuring users’ notes and a simple activity log that displayed edits made to documents created in Notes. However, even the earliest versions of Notes featured functionality that would be preserved in Paper.

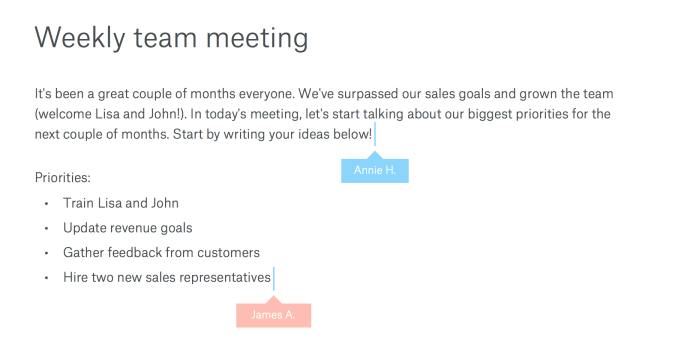

Users could add tasks and embed tables inline within Notes documents. They could easily identify who was working on a document and where they were in a document. Dropbox remained tight-lipped about Notes after the story broke, but it was the strongest indication yet of Dropbox’s intentions.

A little over a year after acquiring Hackpad in August 2015, Dropbox decided to open-source the codebase for Hackpad. This seemed like more of a PR move than a commitment to the open-source community, but it was still long overdue and an olive branch to those users who had objected to Kofman and Graveley’s forking of Etherpad.

Shortly after open-sourcing Hackpad’s code, Dropbox officially rebranded Notes as Dropbox Paper and launched the product’s beta. The company also made some very subtle changes to its logo, including the use of a new typeface, changes that were so subtle that barely anybody noticed.

Initially, Paper’s beta was invite-only. The product itself was only available as a web application that could be accessed directly from within a user’s main Dropbox account.

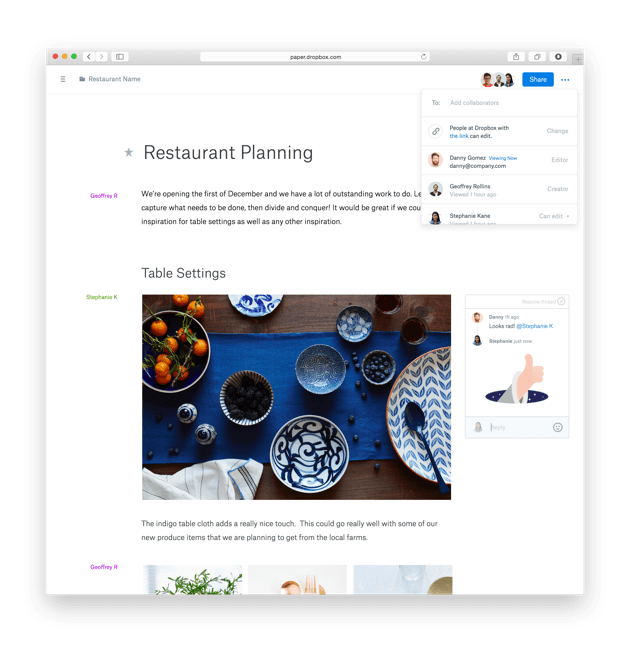

Paper’s interface had barely changed since Notes first emerged. The UI was extremely minimal and featured a lot of white space. Images could be embedded inline, and user comments were presented in a dedicated message pane that separated annotations and comments from the actual notes. It was also practically effortless to see which team members had which permissions in a document, with Creator, Editor, and Permissions labels easily accessed from the Share menu in the upper-right corner.

There was only a single font available when Paper went into beta, and text could only be formatted into three sizes: small, medium, and large. Users could italicize, bold, underline, and strikethrough text. Paper’s use of color-coded usernames was particularly effective against it’s clean white UI.

Although Google Docs was among Dropbox’s most formidable competitors, the earliest incarnations of Dropbox Paper felt more like Coda or Notion than Google Docs.

Adding support for to-do lists and inline embedding of images and tables made Paper much more flexible than Docs is, even now. In this regard, Paper was a remarkably forward-thinking product.

When Paper launched into beta in October 2015, Coda was still being developed behind closed doors, as was the second iteration of Notion.

“Work today is really fragmented. It happens across multiple content types – be it images, code, tables, even tasks. I might be working on PowerPoint. Someone else may be writing code, another in Google Docs –teams have really wanted a single surface to bring all of those ideas into a single place.” — Matteus Pan, former Group Product Manager, Dropbox Paper

Almost a year after launching in closed beta, Dropbox Paper launched in open beta in August 2016 to coincide with the release of Dropbox’s new Android and iOS apps. Following that, though, Dropbox went radio silent for almost two years after the company open-sourced Hackpad’s code.

Dropbox Paper officially launched out of beta in January 2017. By now, Dropbox’s intentions were crystal-clear. Virtually every major move Dropbox had made over the past two years brought the company toward two objectives:

- To refocus the Dropbox experience from a silent background process to a true platform product

- To make Dropbox more useful and attractive to teams, especially in corporate environments

By the time Paper launched out of beta, the product had a whole raft of new features that made the product significantly more useful to enterprise teams. This included Paper’s Presentation mode; the ability to assign tasks and due dates to specific individuals; a native integration with Google Calendar; mobile folder functionality on Android and iOS; and eDiscovery and an API for security tools.

Paper’s eDiscovery and security API, in particular, were crucially important to Dropbox’s mission to expand further into the enterprise. Data-loss prevention, DRM, on-premise backup services, centralized identity authentication – these were all critically important business use-cases that Dropbox hoped would ultimately win out over Google in the enterprise productivity space.

“We’re redesigning Dropbox to be fundamentally designed for teams. We’re reinventing sync, bringing a modern collaboration experience to all your files, and launching Paper, a new way to work together that goes beyond the document. And we’re building this all on top of a strong business foundation — we’ve reached $1 billion in revenue run rate faster than any other SaaS company in history.” — Drew Houston, Co-founder of Dropbox

The next major development came a few months later in April 2017, when Dropbox announced it was formally terminating Hackpad and migrating users’ notes to Dropbox Paper. There was some predictable grumbling from long-time Hackpad users about the move. But for the most part, many people recognized Dropbox’s restraint in allowing Hackpad to continue operating for three years after acquiring it, a rarity in itself.

Upon hearing the news of Hackpad’s closure, some users were concerned that Dropbox would ultimately shutter Paper as it did with Mailbox in 2015 and Carousel in 2016 and their Hackpad notes along with it. But Dropbox arguably had more skin in the game with Paper than it did with any of its other acquisitions. Paper incorporated features from several products Dropbox had acquired in recent years; shutting down the product prematurely would have wasted these considerable investments.

The company badly needed to diversify beyond its core cloud-storage business, and documents were a logical fit for Dropbox. Paper was a strong product with a well-timed entry into a market that had not yet been saturated with competitors. It’s easy to say now with the clarity of hindsight, but these factors put Paper in a much stronger position than Mailbox or Carousel had ever been in.

Dropbox had made little secret of its plans to dominate the enterprise. However, in August 2017, Dropbox released a major update for Paper that took the product in an unorthodox direction.

At that time, most document-editing tools looked and felt a lot like Microsoft Word – especially Google Docs. For all their always-on connectivity to the cloud and collaborative features, most document tools felt like they were designed for working with text.

And for the most part, this was true. Most document tools were designed primarily with text in mind, since most documents tend to be text-based.

However, Paper’s August 2017 update included support for a range of additional document types – many of which were focused on visual designs. The update included native integrations with product design platform InVision and collaborative interface design tool Figma. In addition, Sketch files could now be embedded directly within Dropbox Paper documents and previewed via the web in real time – a great example of the seamless integration between Dropbox’s cloud-storage and Paper.

These features didn’t just make Paper a viable tool for visual designers. It helped Paper appeal to an entirely new audience.

“Whatever you may be making — from new designs to prototypes — Paper lets you build it together from the beginning. Start by tapping out a few lines of text describing the project. Then add context by embedding files from the tools you use every day — including Sketch, Figma, InVision, Marvel, and Framer. You can even pull in Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator files you’ve saved in Dropbox.” — Sheta Chatterjee, former Product Design Manager, Dropbox Paper

Paper’s designer-friendly features were a huge competitive advantage for Dropbox. With the possible exception of digital marketers, few creative professionals work with a more diverse array of tools than visual designers. By integrating several leading design tools into Paper, Dropbox promised to simplify and centralize designers’ entire workflow considerably. For designers working in large, distributed teams, these features were nothing short of a godsend.

For the first time, many designers were able to work truly collaboratively on shared files in real time, rather than accessing shared network drives or emailing large files back and forth.

Paper rounded out 2017 with another major update in December. This time, the focus was squarely on mobile. The ability to create and assign tasks on mobile was added. Paper got a new integration with Microsoft Outlook. Similarly to the Google Calendar integration, the Outlook integration on mobile pre-populated with event information, which could then be shared with meeting attendees effortlessly.

Another cool feature added in this update was the ability to link calendar events in Outlook with specific Paper documents. This made preparing for large meetings a breeze, as Paper could automatically detect forthcoming calendar events and send links to the relevant Paper documents to all attendees ahead of time. These features weren’t just “nice-to-haves”, they were conscious, deliberate attempts to make Paper an integral part of truly collaborative workflows, especially on mobile.

In a little more than three years, Dropbox Paper had gone from a secretive skunkworks project based on a smart acquisition to a diverse, capable document-editing tool with a loyal, growing following. Paper’s support for popular design tools, in particular, was an important competitive differentiator in an increasingly crowded market.

2018-Present: Big Questions, Bigger Opportunities

By the start of 2018, Dropbox was in a strong position. Dropbox was still playing its cards close to its chest in terms of daily active users or monthly active users. But Dropbox’s cloud-storage product had more than 500 million registered users by 2018. Of which more than 11 million of whom were paying subscribers.

Paper itself was also generating a lot of buzz online. Writers loved Paper’s clean, minimalist UI. Designers loved Paper’s support for prototyping and wire-framing tools. Productivity fanatics loved how quickly and easily they could use Paper to take notes, schedule meetings, and organize their work.

Dropbox would soon alchemize that hype into an IPO.

What was most notable about Paper’s journey thus far, though, was how the product simultaneously aligned with Dropbox’s core mission and took the company in a completely different ideological direction.

Prior to Paper, Dropbox’s entire value proposition was the way it ran practically invisibly in the background. With Paper, Dropbox wanted users to start actively engaging with a real product with an actual interface. This signaled a profound shift in how Dropbox wanted its users to interact with its products and services. Dropbox was no longer content to sit idly by while users worked. It wanted to become the platform at the center of that work.

Aside from a significant update in January, the first couple of months of 2018 were mostly quiet for Paper. This was highly unusual. Until this point, Paper’s development cycles had been rapid and aggressive. Granted, Dropbox had gained a valuable head-start by virtue of Hackpad’s acquisition. But the company hadn’t sat idly by, either. Significant updates were released frequently until January 2018, when the pace of the product’s development cycles slowed considerably.

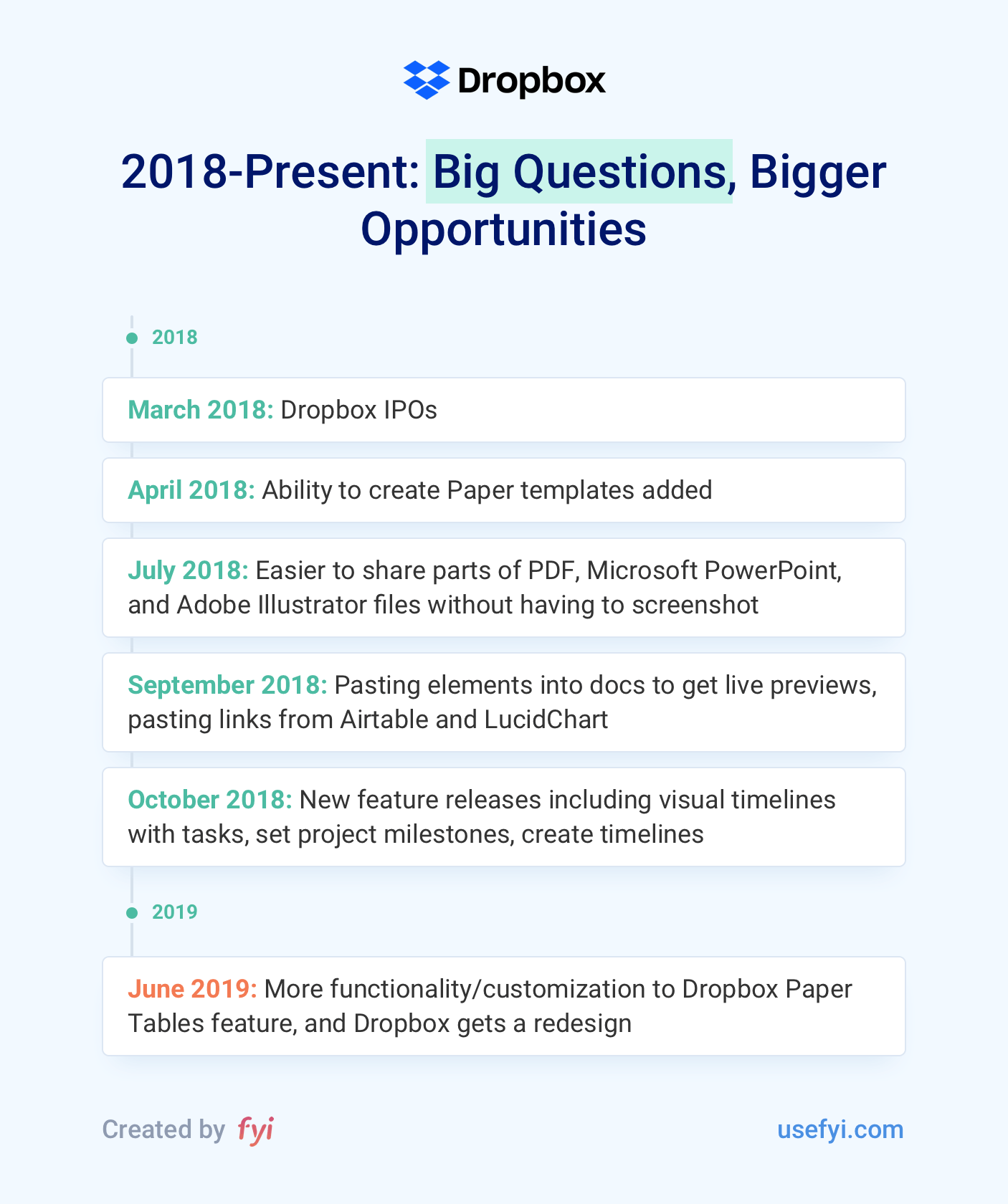

It’s no coincidence that this slow-down occurred perfectly with the company’s preparations to go public, which the company did when it filed its IPO on March 23, 2018.

Dropbox stock began trading at between $16-18. Within moments of the opening bell being rung, Dropbox’s stock had skyrocketed to more than $30 per share, an increase of more than 40%. Dropbox had been valued at more than $10 billion just a year previously.

Although this was crucially important to Dropbox’s first few days of public trading, it wasn’t the real reason why investors were so excited. Investors were hyped because Dropbox had proven that the consumerization of enterprise software was more than a passing fad; Dropbox was one of the very first primarily consumer-focused products that had successfully made the leap not only to the workplace, but to the enterprise.

After enjoying a very strong IPO, Dropbox was valued at more than $22 billion as of March 2018.

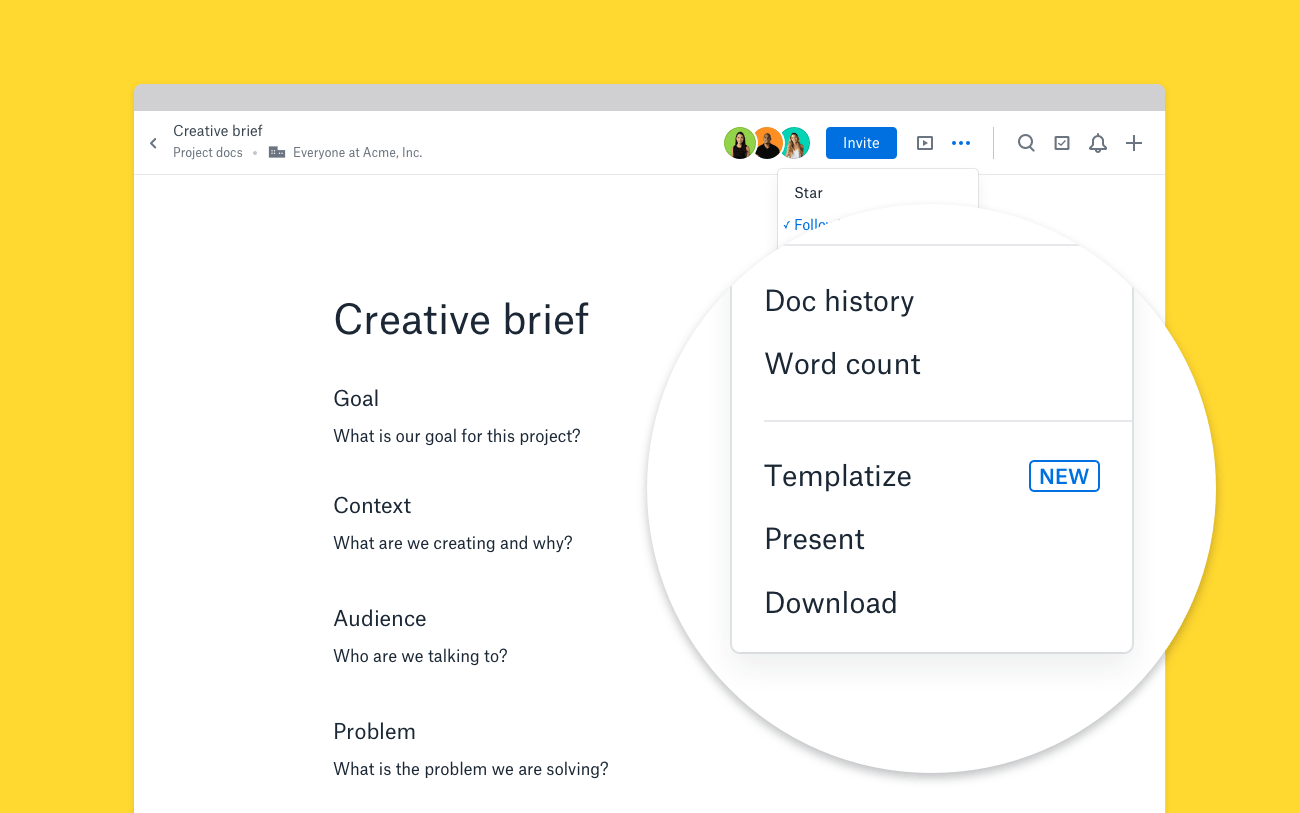

In terms of product, Paper’s next major update came the following month in April 2018 with the release of Templates. However, unlike features of certain competing products such as Evernote’s preset templates, Dropbox Paper’s templates could be defined by users in just a couple of clicks.

Paper did, of course, offer a handful of preset templates as starting points. But the ability to turn any Paper document into a shareable template was what people really wanted. And Dropbox listened.

“Team meeting notes, creative briefs, project plans – you’re probably using the same types of docs over and over again. But pulling one together — tracking down the last doc, copying and pasting into a new one, stripping out the old project’s info – is an annoying, repetitive chore. So today, we’re making your work easier by introducing one of the most requested Dropbox Paper features: the ability to turn any doc into a shareable template.” — George Gerard, Dropbox

With its hugely successful IPO fading in the rearview, Dropbox resumed its formerly aggressive update cycle. Several improvements, bug fixes, and new features were added to Paper over the coming months. These included a feature that made it easier to highlight and share specific parts of PDFs, PowerPoint presentations, and Adobe Illustrator files without relying on screenshots. This might not sound particularly revelatory, but it’s exactly the kind of quality-of-life update that shows users that the little things matter and create more rewarding experiences, especially when it comes to UX.

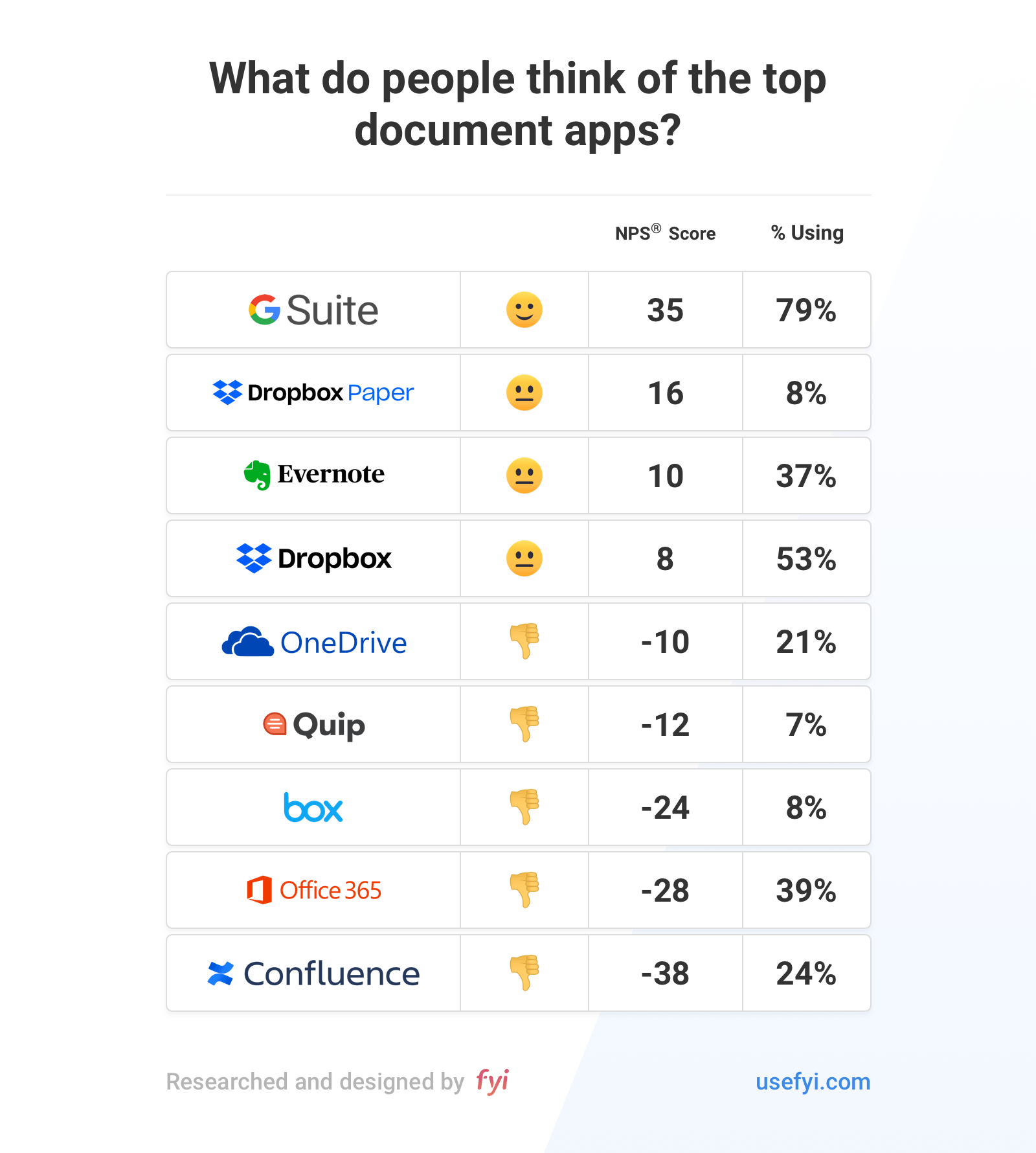

Based on surveys we conducted, these updates helped boost customer satisfaction amongst Dropbox Paper customers. Dropbox Paper’s Net Promoter Score as of July 2018 was a 16, up from -14 a year prior. This was a big, rapid improvement in a category where Net Promoter Scores are not very high to begin with. That means customers went from having bad experiences to being not very satisfied. That’s also higher than Dropbox’s NPS of an 8 and Evernote’s NPS of 10.

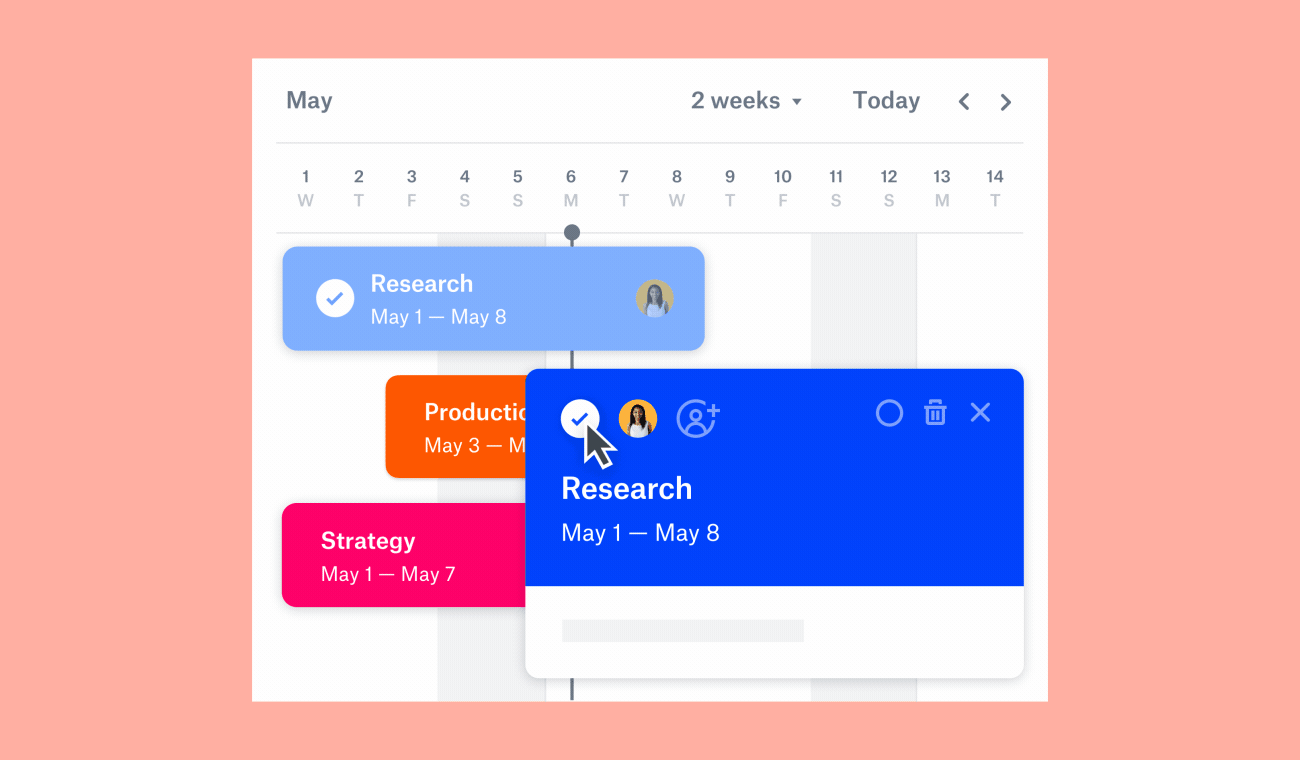

In October 2018, Dropbox took another giant step when it added several project management features to Paper. The biggest such addition was Timelines.

Similar to the chronological planning features of Asana, Paper’s timelines gave users the ability to assign tasks to themselves or colleagues and plan their work visually. Timelines could span periods as short as a week or as long as a year. Users could also add project milestones to timelines, which played nicely with Paper’s existing integrations with Google Calendar and Outlook.

Like its support for embedded design elements before it, the addition of Timelines was a major step forward for Paper as a product. First, Paper had targeted general use-cases such as note-taking, document creation, and collaborative editing. Then it went after designers, an often-neglected audience in the productivity space. Now, Paper was aiming squarely at project management tools like Asana.

This was a risky play. Paper had successfully held its own against Google Docs, Coda, Notion, and many other document tools. It had surprised many users by integrating support for visual design in a smart, useful way that users liked.

Project management, however, was a different animal altogether. This was a brave new world for Dropbox. The company was well-positioned to make the leap into project management tools, but had little experience catering to such a potentially large, albeit niche, market. It also put Paper in the position of competing with even more well-funded, deeply entrenched incumbents such as Asana, which was worth more than $1.5 billion by December 2018.

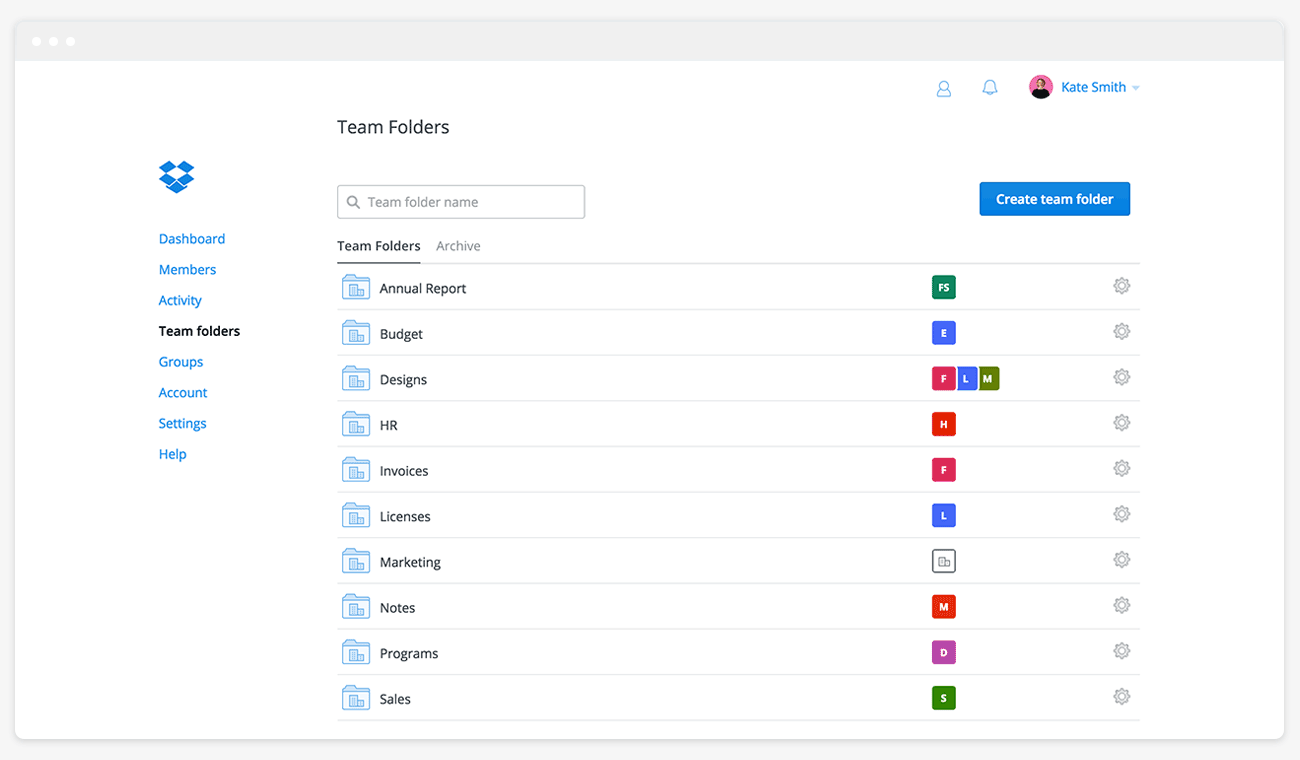

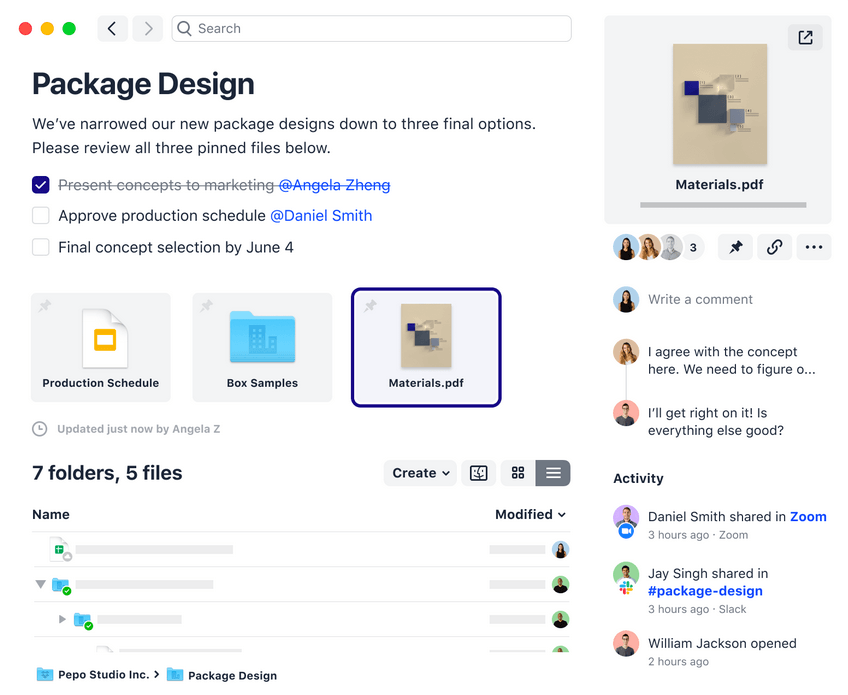

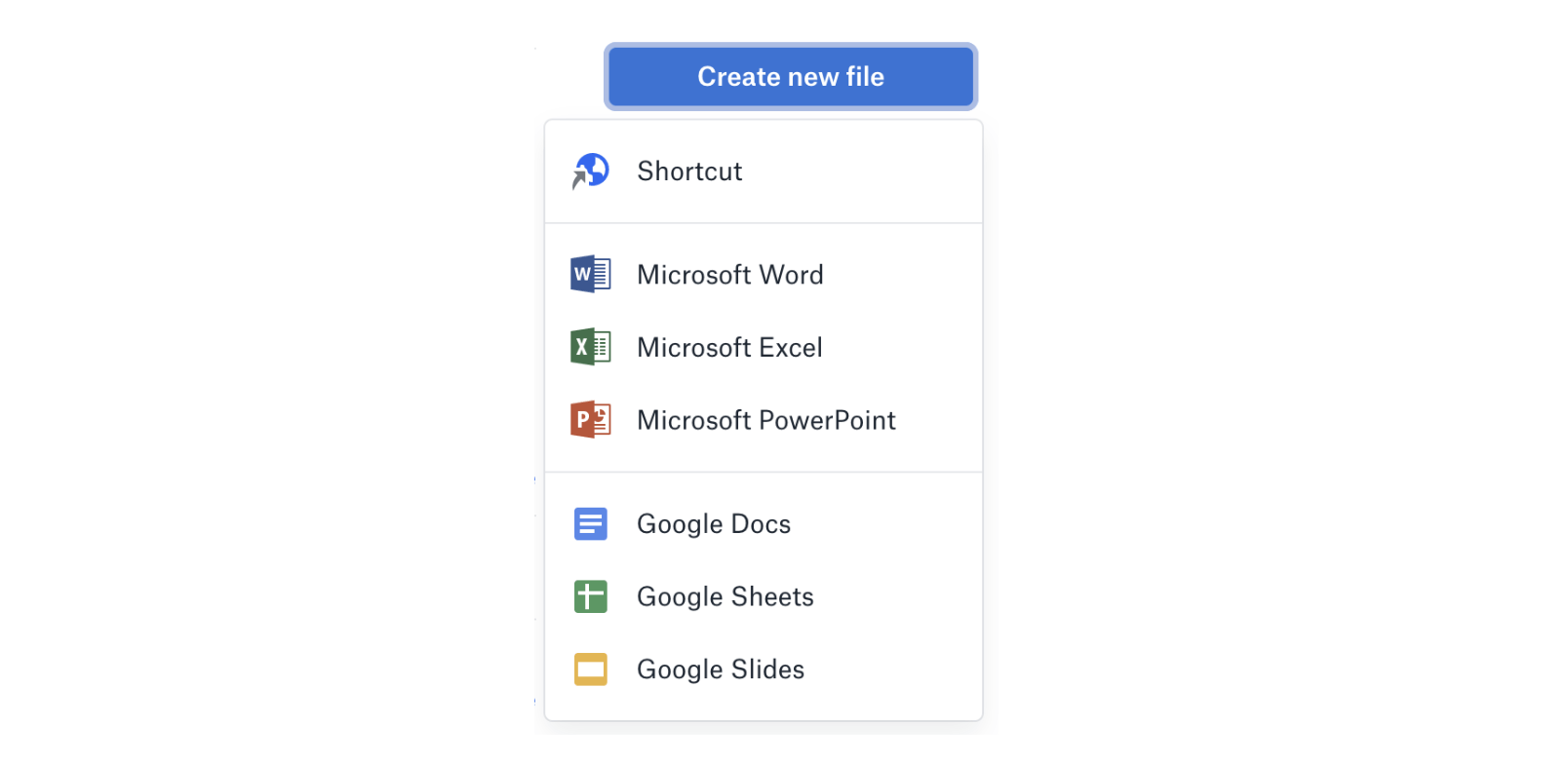

Dropbox’s next major update came in June 2019 when the product underwent a significant overhaul. This was arguably Dropbox’s biggest update ever. Virtually every aspect of the product got a tune-up, redesign, or update. The one exception was Paper. Which was nowhere to be see, at least on desktop.

Amazingly, Paper was hardly featured in Dropbox’s June update at all. For starters, the option to create a Paper document was absent entirely from the Create menu on desktop. It was there on mobile, but missing altogether from Dropbox’s brand-new, shiny desktop app. Even stranger was the fact that Paper documents showed up in both Search and Notifications, but not in the primary Create window.

Paper wasn’t even mentioned in the blog post accompanying the update.

This wasn’t just a missed opportunity. It was actively confusing to Dropbox’s users, particularly Paper evangelists.

After spending so much time, effort, and money on developing Paper, omitting it from the biggest update to Dropbox in years didn’t quite seem to make sense.

Worse, it cast doubt on Dropbox’s plans for Paper and the company’s vision for the future of the product. Was Dropbox planning to shutter Paper as it did Mailbox and Carousel after all? Was the company planning to spin Paper off as an entirely separate product? And most worrying of all would companies that had built their collaborative workflows around Paper have to migrate to another product?

The fact that Paper is not yet fully integrated with the new Dropbox isn’t the problem. It’s that Dropbox didn’t communicate their plans for Paper when it overhauled the main Dropbox product. Even a single sentence acknowledging Paper’s absence in the blog post announcing the update could have gone a long way toward putting Paper users’ minds at ease. If you’re going to ask teams (or entire companies) to build their collaborative workflows around your product, they need to know you’ve got their back and won’t pull the rug out from under them after eighteen months. Failing to even mention Paper in the June 2019 update seemed like a serious error of judgment.

Paper’s conspicuous absence from the June update wasn’t Dropbox’s only problem. The June 2019 update may have been its most ambitious yet. But not everyone was convinced about Dropbox’s new vision of its role in our working lives. On the contrary, many people were confused and disappointed by Dropbox’s radical change in direction.

A common theme among the complaints about the new Dropbox was the fact that Dropbox had seemingly all but abandoned its original mission. It had added lots of stuff, sure, but it no longer did what many users originally signed up for.

“I don’t want any of this. All I want from Dropbox is a folder that syncs perfectly across my devices and allows sharing with friends and colleagues. That’s it: a folder that syncs with sharing. And that’s what Dropbox was. Now it’s a monstrosity that embeds its own incredibly resource-heavy web browser engine.” — John Gruber

Dropbox’s biggest problem isn’t that people don’t like, want, or need its new product. It’s that people associate the Dropbox brand with a passive background process, not a software product that requires active engagement. Dropbox is arguably much more useful than it was in the past. But as John Gruber noted in his withering take-down of the new Dropbox, that doesn’t necessarily mean people want it.

Dropbox’s transition from a synced smart-folder product to an all-in-one collaborative workspace with features aimed at designers and project/product managers is a fascinating case study in how products can and should evolve over time. Despite not integrating Paper with the new Dropbox, the company is in a strong position to leverage its considerable reach to extend further into the enterprise and appeal to new audiences.

Where Could Dropbox Paper Go From Here?

Dropbox Paper’s absence from Dropbox’s most recent major update certainly got people talking about the future of the product. Where could Dropbox Paper go from here?

- Dropbox Paper becomes a full-fledged project management tool. Dropbox has managed to broaden its appeal to both designers and project/product managers in recent years by building out tools and supporting specialized use-cases aimed at these audiences. It’s possible that Dropbox might double-down on its project management tools in the near future by continuing to develop Paper to position it as a potential competitor to existing products such as Asana.

- Dropbox adds more native integrations to Paper. Both Notion and Coda are excellent examples of collaborative workspace products that handle native integrations well. It’s likely that Dropbox will continue to expand the range of native integrations offered by Paper, particularly those aimed at specialized use-cases to attract new audiences to the product.

- Dropbox expands Paper’s functionality to include a greater range of productivity tools. Just as Quip introduced spreadsheets to offer an alternative to Google Sheets, Dropbox Paper may introduce spreadsheets and other functionality to support its growing range of use-cases. We saw this with the introduction of Presentation Mode in 2017.

What Can We Learn From Dropbox Paper?

Dropbox Paper is a great case-study in how companies can diversify their product offerings to serve entirely new audiences and expand into tangential markets. What else can we learn from Dropbox Paper?

1. Over time, figure out what more your product can do. Dropbox wanted to increase engagement with an actual interface. As a document tool, Dropbox Paper was an ideal opportunity to do so. Despite the oversight of not integrating Dropbox Paper into the latest release, Dropbox has generally handled the transition from being a synced backup folder tool to an active organizational productivity tool quite well, a transition other products and companies could emulate.

Think about the original mission for your product and the problem you aimed to solve:

- Could you help your users solve problems that are tangentially relevant to their primary pain points? What are these other problems and how can your product be positioned to help?

- Take a look at your product roadmap, paying particular attention to the list of “nice-to-haves” that haven’t yet made it into your product. How could you quickly build and iterate on rough prototypes of these features?

- How are you identifying and anticipating problems your current users may experience in the future? How could you use this information to add more value to your product?

2. Focus on the problems of the past with historical context. Knowing and understanding the history of why previous products were created helps you align with the needs of today’s customers. It’s not just about solving your customers’ problems, it’s about solving your customers’ problems better than any other product out there.

Consider your product’s place in your vertical or industry, as well as the products that came before yours:

- Be honest. Are you focused on solving your customers’ problems, solving them more effectively than competing products in your space, or both? If you answered “both,” how are you doing so?

- Is it immediately obvious to your prospective customers why or how your product solves their problems more effectively than competing products? If not, how could you communicate this benefit more clearly?

- Think about your most loyal, engaged users. What challenges or pain points are they likely to experience in the future? How can your product adapt to these emerging challenges?

3. Pick a use-case and build around it first. Even when dealing with “outlier” use-cases, building features for the unique needs of specific audiences can be a highly effective growth strategy. For Dropbox Paper, adding support and functionality aimed primarily at designers – a highly specialized audience with unique use-cases – was a huge growth boost for Paper and took the product in an entirely different direction.

Think about your product’s core audience and the problems they face:

- What’s the most marginal use-case of your product you can think of? What steps could you take over the next three months to test whether you could realistically target audiences that need this functionality?

- How could you apply what you’ve learned by developing your product for your primary audience to other potential audiences?

- If you were to mimic Dropbox Paper’s strategy of incorporating support for additional use-cases (such as project management, for example), how would you go about effectively competing with entrenched incumbents as a new player in the space?

Paper Tiger, or King of the Jungle?

Dropbox Paper has grown from a simple productivity tool to a central part of Dropbox’s plans to expand beyond its role as a commoditized storage provider. Despite operating in an increasingly crowded space, Paper has managed to distinguish itself by appealing to specialized use-cases and focusing tightly on the experience of using Paper in concert with other tools.

However, for all of Paper’s popularity, Dropbox’s competitors are unlikely to allow the company much breathing room as the sector’s biggest players continue to vie for dominance. How Dropbox handles its next moves will play a huge role in the likelihood of Paper’s ongoing success.

Will Dropbox Paper end up as a Paper Tiger or King of the Jungle? Only time will tell.

Do you use Dropbox Paper? You can find your Dropbox Paper documents, alongside documents from other apps, in 3 clicks or less by using FYI.