How Notion Is Going After Atlassian and Why It Just Might Win

Admitting a mistake can be incredibly difficult for some founders. They become so invested in proving the validity of their original idea that their businesses fail. Not every founder falls into this trap but many do.

Ivan Zhao, co-founder of Notion, found himself in this exact position in 2015. Having launched a no-code tool, Zhao was confident his vision of the future was the one that would come to pass. He had evaluated the landscape of collaborative productivity tools at that time, and made an educated guess about what the future had in store.

However, even educated guesses are just that, guesses.

Zhao’s instincts were wrong. The world didn’t want another no-code app-building tool, at least, not then. Rather than allow that to stop him, Zhao and his team relocated from San Francisco to Japan, went back to the drawing board, and reimagined what the world really needed: A collaborative workspace tool. A period of self-reflection not only saved Notion as a product, but actually put the company on an entirely different growth trajectory.

I sat down with Ivan at Notion’s offices to talk about his journey. Here are some of the things we talked about:

- Why design has been central to Notion’s philosophy from the outset

- How the product overcame its initial limitations and succeeded in a crowded market

- How Zhao’s relentless focus on Notion as a product helped the company achieve lean growth

When Notion first launched in 2015, the market for collaborative productivity tools was already intensely competitive. Zhao envisioned Notion as an all-in-one productivity tool that would replace everything besides email and Slack. However, as Zhao soon realized, he’d been betting on what he thought the world needed—not what it actually needed.

2015-2017: No Code, No Competitors… No Problem?

Notion didn’t begin life as an all-in-one productivity tool. In actual fact, it was much closer to Airtable and other tools in the “no code” movement.

Originally, Ivan Zhao wanted to create a way for anybody to create their own applications without writing a single line of code. Interest in programming bootcamps, building apps, and launching tech startups had reached fever pitch by 2015, and Zhao believed that his tool would empower an entire generation of entrepreneurs.

The only problem was nobody wanted that tool.

“We focused too much on what we wanted to bring to the world. We needed to pay attention to what the world wanted from us.” — Ivan Zhao, Co-founder of Notion

Prior to developing his first tool, Zhao had been designing and building websites for friends for years. During that time, one thing that consistently struck Zhao was that, despite the importance of technology to his friends’ day-to-day work and their lives in general, very few people had the skills necessary to build or modify their own tools.

Zhao’s first product was focused primarily on programming. He later realized that most people wanted to use tools that combined the features and functionality of tools they were already familiar with and using, rather than learning a brand-new tool from scratch.

However, the biggest issue with the original product wasn’t necessarily that there was no demand for another no-code product—though that was a factor. The biggest issue was that Zhao and his co-founder, Simon Last, had built the product using a tech stack that couldn’t possibly scale. Stability was a major problem and the product crashed frequently.

With little money and fewer prospects, Zhao and Last made an incredibly difficult choice: either dissolve their four-person company and start over, or limp along until they finally ran out of runway.

It was no choice at all.

Zhao and Last made the decision to sublet their office in San Francisco and make a fresh start in another city. Their destination? Kyoto, Japan’s former Imperial capital.

“If you look on Airbnb, the houses in Osaka and Tokyo are very different. Kyoto’s houses seemed to be larger. Tokyo was tiny little shoe boxes. Simon and I didn’t want to be crammed together while coding. Plus we could bike around everywhere. That was where we completely rebuilt Notion.” — Ivan Zhao, Co-founder of Notion

To Zhao, very little had changed since the days when IBM mainframes occupied entire rooms and filing cabinets were the preferred means of information storage. Rather than combining the tools we use every day, Zhao observed that software companies had merely created digital versions of legacy systems. This antiquated perception of work itself had created a fractured mess of apps, tools, workspaces, and file systems—none of which seemed to interact well with one another.

During development of their original product, Zhao and Last had collaborated extensively using Figma, a collaborative design and prototyping tool. Although Figma allowed Zhao and Last to design, code, and collaborate on their project, they still had to rely on a multitude of tools to get their work done. This gave Zhao an idea—what if there were a single tool that could do practically everything people needed to work together?

This is what Zhao and Last would offer the world.

“Neither of us spoke Japanese and nobody there spoke English, so all we did was code in our underwear all day.” — Ivan Zhao, Co-founder of Notion

It was during Zhao’s time in Kyoto that the product’s design became a singular driving force behind Notion’s development. From major UI configurations to the tiniest details, virtually every single aspect of Notion’s appearance and aesthetic went through an intense iterative design process.

Zhao, in particular, was practically obsessed with what he calls “permutations.” As Zhao and Last worked on Notion 1.0, the pair would create a single flow over and over again, making only slight alterations each time until they were satisfied they had found the optimal choice for each feature.

This exhaustive approach to design permutations didn’t just make Notion a significantly better product—it informs how Notion does just about everything. To this day, creating multiple permutations is a hallmark of Notion’s approach, with most employees creating multiple versions of everything they do to ensure every choice is sufficiently stress tested. Zhao’s iterative design philosophy has become a central part of Notion’s culture as a company.

Zhao and Last had worked almost nonstop on their original idea for almost a year. Zhao was still passionate about the spirit behind the original product—empowering people to create without coding—but the two had few concrete ideas on what to build. That changed when Zhao and Last examined how they’d been working together.

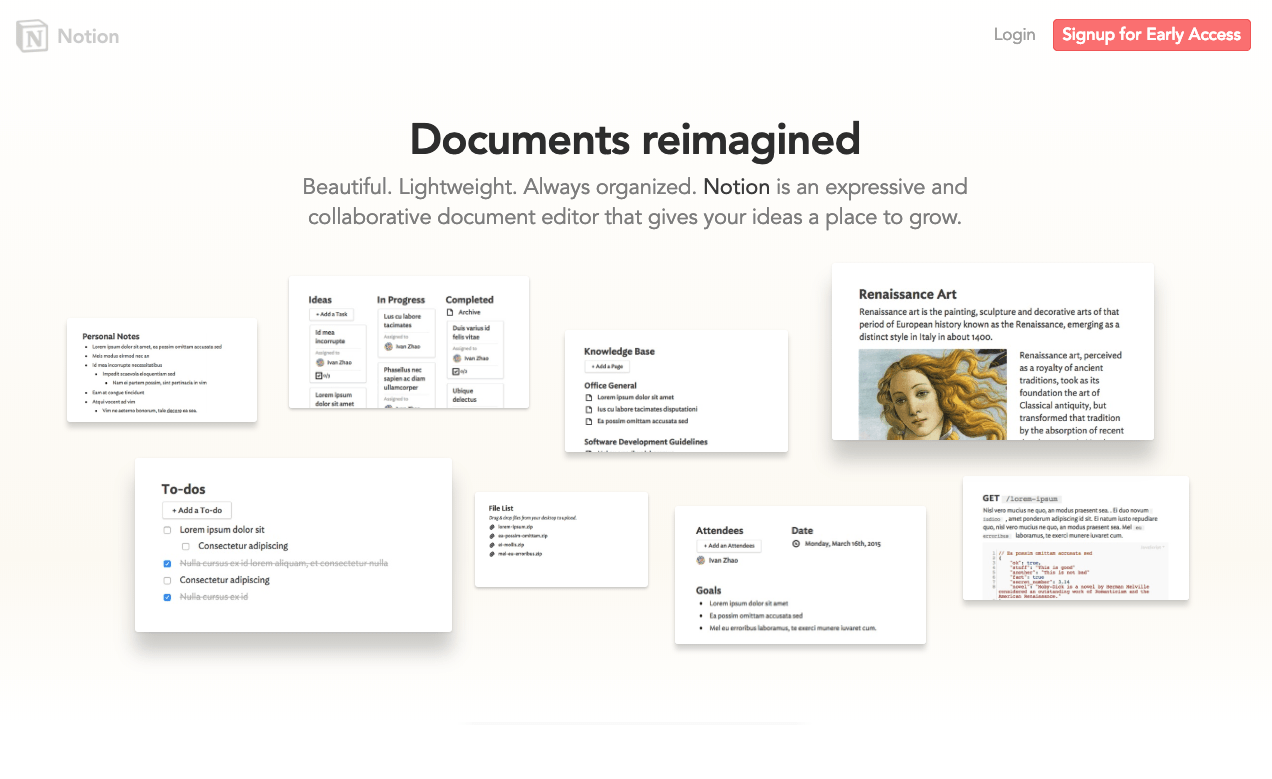

Their product would combine almost every workspace and productivity tool besides email and instant messaging into a sleek, elegant design—a tool for what Zhao described as a “post-file, post-MS Office world.”

Developing an all-in-one tool might have seemed risky, particularly in light of the first iteration of Notion’s failure, but it’s actually a very common strategy in crowded markets. HubSpot, Hotjar, and Intercom are all great examples of companies that built solid all-in-one products to gain entry into their respective markets. What made Notion so interesting was that, although it wasn’t the first all-in-one productivity product, it was the first that wasn’t focused exclusively on documents. You could collaborate and work on documents, sure, but they weren’t the sole focus of the product. This gave Notion significantly more utility than any other tool on the market at that time and appealed to a much broader range of use-cases.

“The market is huge—everyone with a computer.” — Ivan Zhao, Co-founder of Notion

After almost a year of hard work in Japan, Zhao and Last were finally ready to unveil their product to the world. And, in March 2016, Notion 1.0 launched.

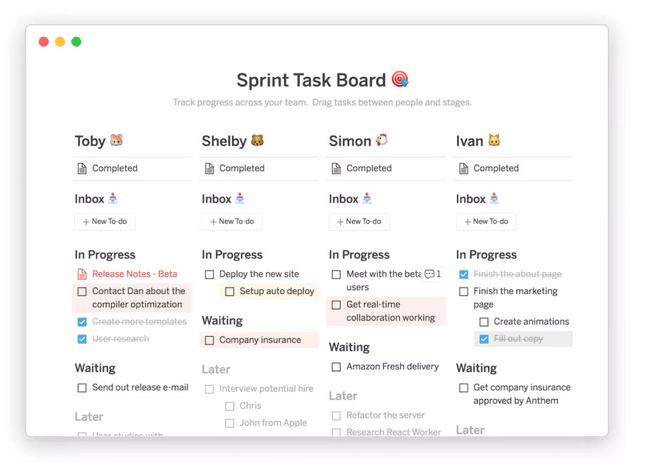

Initially, Notion was available as a web application and for OS X. Even initial versions of Notion were remarkably fully featured. At launch, Notion supported:

- Drag-and-drop, Kanban-style to-do lists

- Wikis and internal documentation

- Product roadmaps

- More than 30 document templates

Early adopters were impressed. Notion could handle a robust array of tasks, and looked and felt great to use. The product’s drag-and-drop functionality made editing and organization a breeze, and Notion’s impressive range of document templates covered a range of use-cases, from internal documentation and design specifications to project lists and image repositories.

Many users were particularly impressed by Notion’s wiki tools. When Notion launched in 2016, the only real competitor it had to contend with was Atlassian’s Confluence. Although Confluence had a much more robust set of features than Notion, Confluence’s learning curve and its target audience of software engineers made it intimidating to newcomers, and impractical for casual users. Notion’s wiki tools were arguably as strong as those of Confluence, but the app could do a whole lot more besides—not to mention the fact that it was significantly cheaper and much more user-friendly.

Of course, Notion 1.0 wasn’t perfect. A common thread among initial user feedback was that, while Notion did a lot of things quite well, it didn’t excel at any one particular task. This is very common among all-in-one products. They ship with plenty of features, but don’t do any one thing incredibly well yet. This is why users who are looking for a generalist, all-in-one tool rather than the “best” tool for a specific task are ideal early adopters for products like Notion.

“You work on something long enough, you realize it’s not about you, it’s about people loving what you are building. If you keep doing that, the market will drag you where you should be.” — Ivan Zhao, Co-founder of Notion

Shortly after launch, Notion got its first real update—the ability for users to comment on Blocks. Almost everything in Notion is a Block. Images, text, spreadsheets, and to-do lists are all created using Blocks. All users had to do to comment on a Block was simply right-click on it and add their feedback.

The following month, Notion announced its first integration, which allowed users to connect Notion to Slack. Notion wanted to replace dozens of tools with a single, elegant workspace. The only elements Notion never really wanted to go after were email and instant messaging. Building an email client into Notion wouldn’t have made much sense, nor would a native IM client. There were already dozens of email tools available, and convincing people to switch email clients would have likely deterred many prospective users. Similarly, developing its own IM client for Notion didn’t make sense, either. By 2016, Slack had raised more than $540 million and had more than 3 million users worldwide. Going after Slack would have been suicide—but integrating with Slack was brilliant.

The product’s next major update didn’t come until almost a year later when Notion debuted its app for Windows in May 2017. The following month, Notion released its iOS app, which was a major turning point for the product. Users had been clamoring for an iOS version of Notion since launch. Releasing its iOS app dramatically increased Notion’s potential userbase. However, having been burned by an unstable tech stack in the past, Notion smartly opted for an invite-only release to ensure the product remained stable as the number of users increased.

June 2017 also saw major improvements made to Notion’s search functionality. The most notable change was the inclusion of keyboard shortcuts that allow users to find what they’re looking for much faster. The search function works similarly to Slack’s ⌘ Shift-K command, and was implemented to make Notion’s formerly clunky search function easier and more intuitive to use. At that time, Notion’s search function still lacked some more advanced features such as boolean operators, but it was a necessary step in the right direction.

“There was a lot more diverging in the early days. We were studying the history and all the dead products on the path. But it’s fundamentally about solving people’s problems. Do we make them more productive at work? Do we solve their daily needs?” — Ivan Zhao, Co-founder of Notion

Having realized that his vision for Notion conflicted with the needs of the market at that time, Zhao correctly took Notion back to the drawing board to see where the company and product had gone wrong. After successfully course-correcting and relaunching a revitalized product, Notion began 2018 in a very strong position—momentum the company leveraged to great effect in the coming years.

2018-Present: Building a Better Way to Work

Although Notion 1.0 was released in March 2016, neither the company’s founders nor the company itself considers the first version of Notion as Notion 1.0. To Zhao, Notion 2.0, which was released in March 2018, was much closer to his original vision for what Notion should be. Zhao’s company had built a sleek, elegant, fully featured all-in-one workspace tool that was lightweight enough to appeal to casual users but robust enough to handle more demanding tasks. What Notion had to do next was build out more powerful functionality to appeal to more use-cases.

“In all honesty, Notion 2.0 is really the 1.0 for us. It finally delivers on our promise—a singular tool that handles all your work outside email and Slack. With the addition of tables, Kanban boards, and calendars, along with the existing notes and wiki features, we think we have done it with this release—Notion is now truly the ‘all-in-one workspace.'” — Ivan Zhao, Co-founder of Notion

When Notion 2.0 launched in March 2018, two things happened that drove immense growth and put the company on an entirely new growth trajectory.

First, Notion 2.0 shot to the top of Product Hunt, later becoming the #1 Product of the Month for March 2018. Second, Notion was featured in a glowing write-up by David Pierce published in The Wall Street Journal. The article precipitated a dramatic spike in users, most of whom continued using the product long after the initial hype died down. At this point, Notion had a grand total of less than 10 employees.

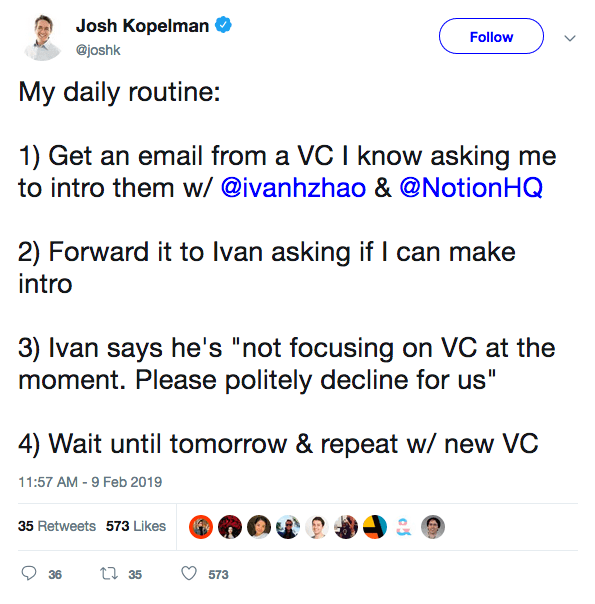

The exposure from Product Hunt and The Wall Street Journal drove amazing growth. This, in turn, led to a feeding frenzy of venture capitalists hungry to invest in Notion. Before long, VCs were literally knocking on Notion’s door in the hopes of securing a meeting. That was in addition to the multiple calls Zhao received every single day. Notion was being courted so aggressively that the company decided not to update the office address in its Google listing to try and stem the tide of cold-call in-person drop-ins. Zhao soon became notorious for declining to even speak with interested VCs himself.

It’s important to note that Zhao wasn’t—and isn’t—against venture investment on principle. Notion accepted an undisclosed sum as part of a seed round in 2017, and Zhao often acknowledges the crucial role this seed funding played in Notion’s early development.

“At this moment, how does extra capital help us grow? Right now, it’s about the quality of the team, it’s our distribution model and pipeline. More capital isn’t necessarily going to make those things better, faster. Again, we’re not anti-VC. It’s more about helping us focus on product and less on meetings.” — Ivan Zhao, Co-founder of Notion

That said, Zhao and Last have always been strongly product-focused founders. They had to be. They wanted to build an all-in-one product that would eliminate the need for dozens of individual tools and essentially redefine how people worked—the “post-file, post-MS Office world” Zhao envisioned years before. This demanded not only a lot of faith in the product itself, but the courage to wait things out and see whether the world was ready for—and needed—what they were building.

It also demanded a keen sense of self-awareness about Notion as a business and how Zhao and Last wanted to run their company. They wanted to focus solely on the product and how to get it right before worrying about seeking capital investment to scale. “Our seed round has given us a good opportunity to be more thoughtful to play for the long game rather than optimize for the next round,” Ivan explained.

Zhao’s attitude to venture capital isn’t a mere reluctance to accept external investment and the inevitable loss of control that typically follows. It aligns strongly with Zhao’s philosophy for Notion itself. Zhao understood that more money and more people wouldn’t necessarily mean a better product or faster development. He was already trying to find the right problems to solve—problems with solutions that didn’t require millions in venture capital or vast engineering teams.

“Hire as few people as possible. If you hire, it almost means that your current team hasn’t done a good enough job to pull it off.” — Ivan Zhao, Co-founder of Notion

In June 2018, almost exactly a year after the beta of Notion’s iOS app went live, Notion unveiled its long-awaited Android app. It also introduced a new price-point of $4 per month aimed at personal users. This made Notion significantly more affordable than Evernote, which at that time cost $70 per year. However, while the price was definitely right, the product itself still had some issues.

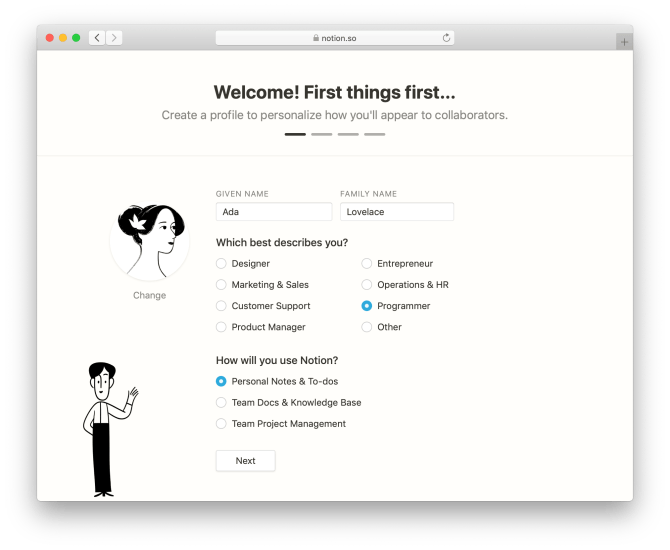

Notion had carefully optimized its onboarding flow throughout the product’s development. Users were guided through setting up an account based on the use-cases that best described the user’s job role and which tasks were most important to them. Each feature was explained clearly, as was how users could navigate between Notion’s various templates.

However, despite Notion’s thoughtful onboarding, the product itself wasn’t as accessible as it could have been. Notion’s minimal design aesthetic belied the power of the product underneath. Creating even a simple note presented the user with multiple templates and options, which made simple tasks such as jotting down a quick note much more intimidating.

“When it comes to taking notes, speed is paramount, and the feature set is secondary. Testing Notion over the past couple months, it could feel like I was using a Lamborghini to do a task better suited for an electric scooter.” — Casey Newton of The Verge

Notion’s power wasn’t the fact that it literally did away with the need for dozens of individual tools. It was the product’s underlying relational databases. From the beginning, Zhao had wanted to empower people to create applications without using code. On the surface, Notion looked and felt a lot like a document-editing and collaboration tool. Under the hood, however, was where the real muscle was.

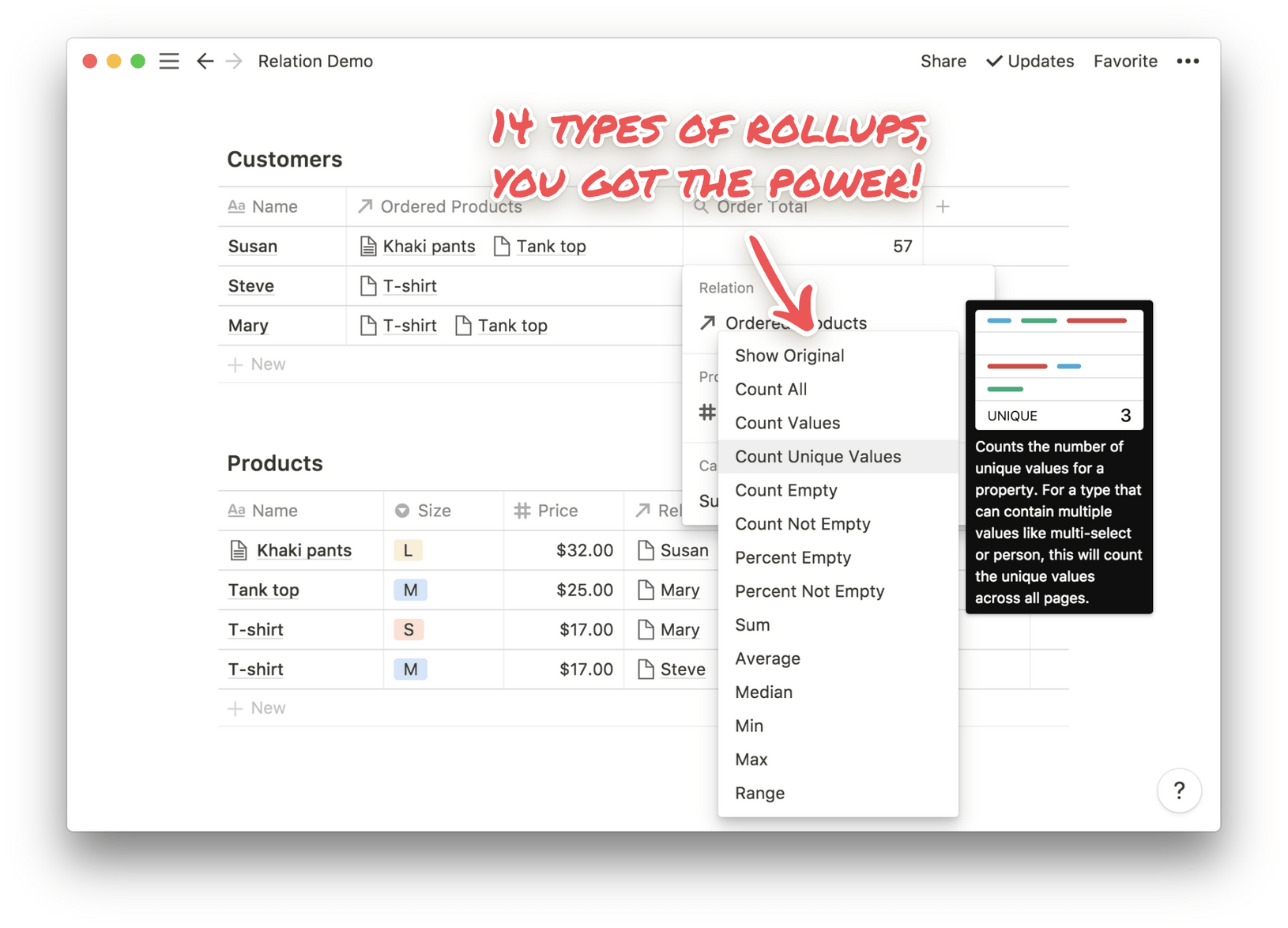

The company doubled down on Notion’s database functionality in September 2018 when it introduced Rollups. This feature allowed users to connect and create rollups of relevant data gathered from multiple relational databases to create custom views of tabular data.

Rollups launched with fourteen different types of rollup, including Sum, Median, and Range. The learning curve of Rollups may have been a little steep for new users, but it’s an amazingly powerful feature that empowers users to create relational databases in a way that only programmers could do previously, such as building a lightweight CRM.

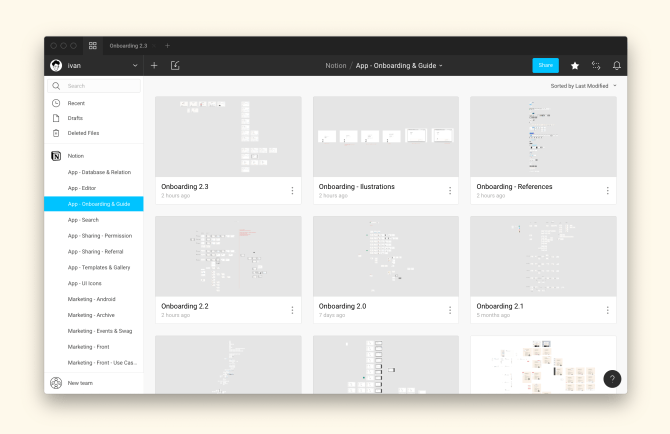

October 2018 was a big month for Notion. The company moved into new digs in San Francisco’s Mission district. Shortly afterward, Notion introduced Gallery View, which gave users a handy visual overview of their data. Next, Notion added Pages, which offered users even more document templates for a broader range of use-cases.

In March 2019, Notion introduced its one-click Evernote importer.

As its name implies, this feature allows users to import all their Evernote notes and notebooks directly into Notion with a single click. Although this feature had been on many users’ wish-lists for some time, the launch of the Evernote importer was a bold move that helped Notion attract Evernote users who had grown weary of Evernote as a product. It was among Notion’s most aggressive moves to date.

Notion wasn’t coy about going after disaffected Evernote users. The company didn’t mince words or rely on vague generic implications—it went after Evernote by name. When Notion launched its Evernote importer, the product’s homepage featured a dedicated “Switch to Evernote” page featuring an illustration of a user dismounting an elephant—known affectionately to Evernote loyalists as “Mads” the elephant—to symbolize leaving Evernote for Notion. The calls-to-action beneath the illustration made it practically effortless for Evernote users to import their notes and data into Notion.

Alongside its Evernote importer, Notion also debuted its Web Clipper extension for Google’s Chrome browser in March 2019. This tool functions similarly to Evernote’s own Web Clipper. Once the extension is installed in Chrome, all users have to do is click it to clip a page to Notion, where it can be saved to a specific location, annotated with comments, shared with colleagues, or converted to a task.

“Collaborating with a team is easier when you structure the data. No one will ever read your Bear notes or Evernote notes, so it doesn’t have to be structured. But for team-based work, you need a super-powered structure to make things collaborative, and less ambiguous.” — Ivan Zhao, Co-founder of Notion

One thing that Notion and Evernote share, however, is their focus on lightweight use-cases—the casual, individual users who fall in love with an app, then bring it with them to work. Slack utilized this strategy to great effect during its earlier growth stages. Evernote attempted to do so, but missed the mark. Zhao, on the other hand, remained focused on these lightweight use-cases, as he understood the value in maintaining the product’s appeal for individual users as a growth vector.

As of last month, Notion had more than 1M users—a feat made all the more impressive by the fact that Notion has just eighteen full-time employees. The release of Coda earlier this year was seen as a potential threat to Notion, but Coda’s lack of a structured, connected workspace means that, for now, Confluence remains Notion’s only real competition. The company will have to tread carefully if it hopes to maintain its momentum, but Zhao’s relentless focus on the product and his keen sense of awareness will likely serve him and Notion well in the coming years. I can’t wait to see what they do next.

Where Could Notion Go From Here?

Notion has grown incredibly quickly in a short time, and seems poised for even greater growth in the future. Where could Notion go from here?

- More importers. The addition of the Evernote importer was a predictable but logical move for Notion. One of the company’s most obvious next moves is the inclusion of additional importers for other tools. It’s feasible that Notion may introduce an importer for Confluence user data as competition between the two companies intensifies.

- More integrations. Notion has always been part of the no-code movement, which makes additional integrations with other products practically an inevitability. Integrating with Slack was a brilliant strategic move that effectively allowed Notion to shore up one of its few weaknesses as a product. A similar strategy with other products and tools—such as email—seems highly probable.

- Fixing Notion’s rough edges. As impressive and robust as Notion is as a product, it’s not without its flaws. As Notion grows and expands further into the collaborative workplace, the company will have to address some of the legacy issues that have marred Notion for some time. Notion’s engineering and product teams have been working hard to solve stubborn problems such as the product’s speed, and additional fixes and tweaks are in the works.

What Can We Learn from Notion?

Having come perilously close to disaster, Notion rebounded and pivoted to become a beloved product with a strongly loyal userbase. What can we learn from Notion’s journey thus far?

1. Self-awareness is critical. Notion 1.0 was a valuable learning experience for Zhao and Last. Although packing up and moving to Japan might have seemed extreme, it was a great example of founders doing whatever it took to move beyond a discouraging experience, refocusing on their core mission, and building a product that people really wanted.

Think back to a time when you experienced doubt about the future of your company or product:

- Were there any steps you considered taking that felt too risky? How might taking these steps have impacted the development or growth of your product?

- How did you arrive at your original idea, and what happened to make you question whether you were on the right track?

- Before settling on the idea for your product, did you attempt to solve an existing problem without a solution, or did you go in search of a problem?

2. Predicting future trends is as much an art as a science. Prior to developing Notion 1.0, Zhao and Last evaluated the landscape of productivity tools and made an educated guess about where the world of work was heading. Their initial instincts may have been a little off, but they managed to refocus and create a product that solved a real problem in an elegant way.

Take a look at your product, its place in your industry, and where that industry is headed:

- Why do you think your industry will go where you think it will go?

- What will your company do if you’re wrong?

- How easily could you pivot if you overestimated the demand for your product?

3. Adding more people can actually slow you down. At almost any point after Notion’s launch, the company could have easily accepted millions in venture capital to expand the team and grow faster. However, as Zhao is fond of saying, three Herman Melvilles probably wouldn’t have written Moby Dick much faster than one. In some cases, more people can be more of a hindrance than a help.

Think about your company’s current headcount and your projected growth:

- Ignoring practical costs such as salary and benefits etc., if you could somehow hire an additional 20 engineers, how would this impact development of your product?

- How do your hiring plans align with your product development roadmap? Put another way, would hiring more employees actually align with where your product or company is headed?

- Every company wants every single hire to be the best possible hire for that role. Thinking about your hiring process thus far, have you prioritized finding the best people, or enough good people?

An Altogether Different Notion

Notion’s journey as a product has been fascinating and instructive to entrepreneurs and founders of all types. However, the most fascinating aspect of Notion as both a product and a company has been how relentless Zhao and Last’s focus on their product has been, and the outsized impact this has had on perceptions of the product among the community.

Although I’m intrigued to see what Notion will come up with in the future, how the company will fend off—and perhaps ultimately defeat—Atlassian’s Confluence will be arguably even more interesting.