How Google Moved Beyond Search to Reinvent Productivity with G Suite

The paradigm shift from desktop to the cloud is arguably the single most important transition we’ve seen in modern computing since we first went online in the ’80s. The past fifteen years in particular have seen an exodus of companies migrating their products from desktop clients to cloud-based services, and Google has been a pioneer of cloud-based freemium SaaS from the very beginning.

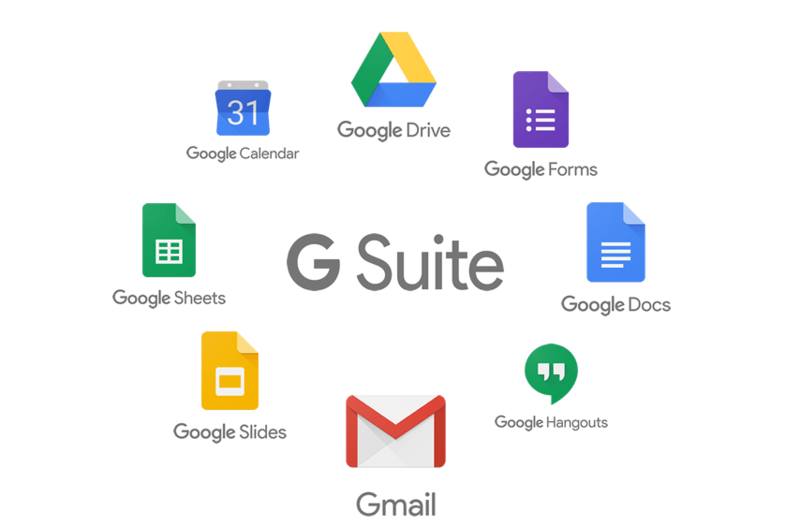

Google’s G Suite was many people’s first taste of cloud-based products. However, what became one of the world’s leading suites of productivity tools began almost accidentally with the launch of an internal product at Google. That product was Gmail, and it changed everything—not just email. It represented the company’s first tentative step beyond search. They followed up that success with Google Docs, Sheets, Slides, and more, a collection of tools that ultimately became G Suite.

Today, G Suite is used by millions of individuals and businesses all over the world. Despite the ubiquity of G Suite and the resources Google has at its disposal, Google’s primary competitor in this space—Microsoft—is a fearsome opponent. The battle between the two tech giants shows no signs of ending anytime soon.

Here are a few of the things I’ll be looking at in this article:

- How Google has applied consumer-focused design to a product suite aimed primarily at the enterprise.

- Why G Suite was so strategically important for a company that has historically relied on advertising revenue.

- How Google retains the culture of experimentation it pioneered in its early days, even as the company has grown massively—and how this culture drove the development of G Suite.

Gmail wasn’t designed to be a standalone product, but an internal tool. It quickly became apparent that Google’s latest project had vast potential—and Google wasted little time in exploring that potential.

2004-2010: Moving Beyond Search

In October 2018, Google announced that Gmail had surpassed more than 1.5B users making it the most popular email client in the world. What ultimately became one of Google’s most popular products was created by a single developer, Paul Buchheit, in just one day back in 2004.

Buchheit had been fascinated by the idea of a web-based email client since his days as a college student, when he had worked on a personal web-based email project—before even Hotmail became the first big web-based email service in the late ’90s. Previously, Buchheit had worked on Google Groups, and was tasked with creating “some type of email or personalization product” as a 20%-time project.

In just one day, Buchheit created the first version of Gmail using JavaScript—the first email client to do so—and repurposed code from Google Groups. It was the first Google product beyond its core search engine and it would change the entire trajectory of Google as a company.

Gmail was officially unveiled on April 1, 2004. In the press release accompanying the launch, Google announced that Gmail would offer users a massive 1GB of free storage—500 times more storage space than Hotmail, which Microsoft had acquired back in 1997 for a comparatively paltry $500 million. Between the timing of the press release and the stunning amount of storage space, many people thought the announcement was another characteristically clever Google April Fool’s Day hoax.

Initially, Gmail was invite-only. However, unlike Hotmail, Google didn’t have to rely on promoting the service at the bottom of each email to attract its initial users. Most email clients at that time offered between 2-4MB of storage. In comparison, Gmail’s 1GB of storage was almost quite literally unbelievable. Combined with the tool’s simple yet highly accurate keyword-based search functionality, Gmail was powerfully attractive.

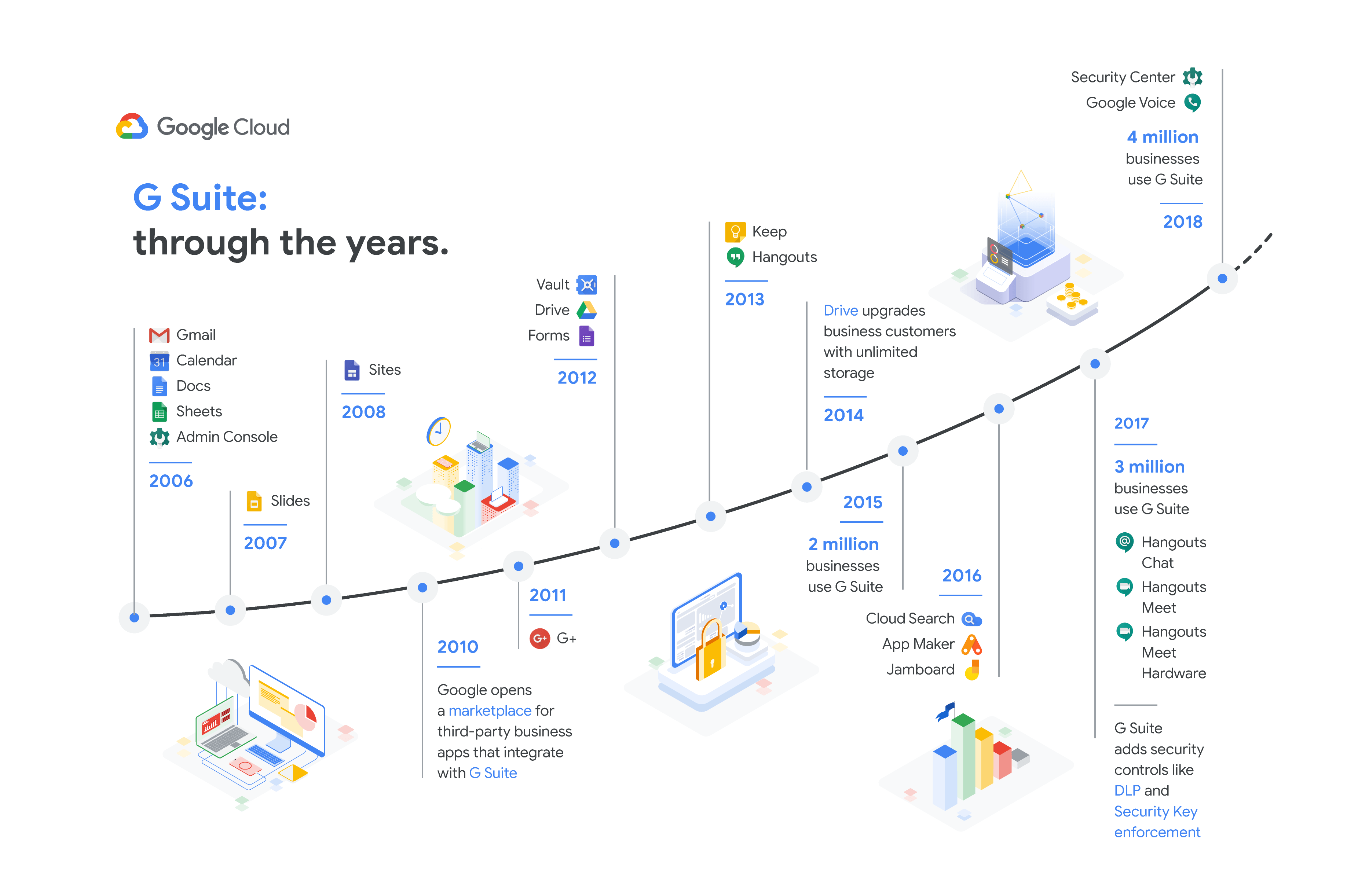

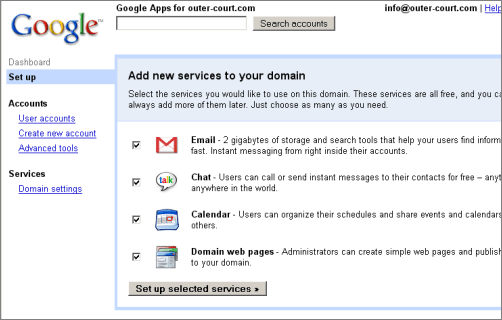

As word about Gmail spread, Google was already hard at work on the next set of tools that would fundamentally change online productivity. In February 2006, Google launched Gmail for Your Domain in a limited beta. Gmail for Your Domain allowed site administrators to customize Gmail for business use, giving them the power to use custom domains in Gmail accounts instead of the default @gmail.com domain. Just a few months later in August, the company launched Google Apps for Your Domain, an extension of Gmail for Your Domain that incorporated three brand-new tools: its Google Talk instant messaging client, its HTML editor Google Page Creator, and Google Calendar.

“Organizations of all sizes face a common challenge of helping their users communicate and share information more effectively. A hosted service like Google Apps for Your Domain eliminates many of the expenses and hassles of maintaining a communications infrastructure, which is welcome relief for many small business owners and IT staffers.” — Dave Girouard, former Vice President and General Manager of Enterprise, Google

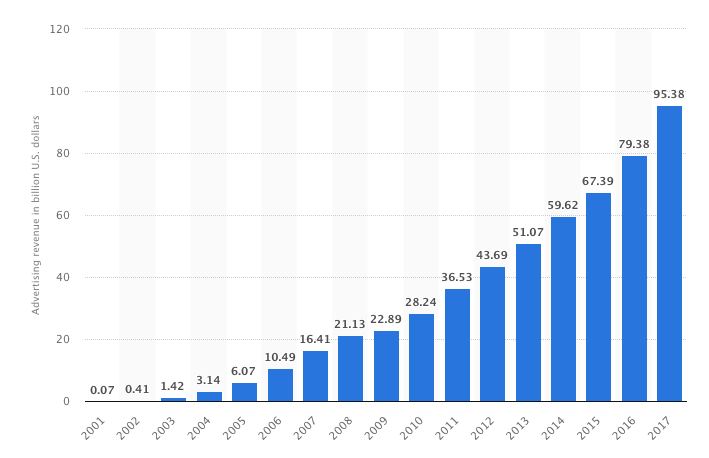

With the launch of Google Apps for Your Domain, Google had made its intentions clear. Yet, it wasn’t immediately apparent why a suite of cloud-based productivity apps was a logical move for Google, given the company’s strong focus on search and online advertising. However, in hindsight, it was beautifully simple.

AdWords wasn’t just Google’s primary revenue stream. It was a vast treasure trove of user data. Even in 2006, AdWords was generating more than $10B in annual revenue for Google. In addition to billions of dollars, AdWords offered Google incredible insights into the needs and challenges facing small-business owners. Challenges that Google Apps for Your Domain could help them overcome. The launch of Apps for Your Domain was the first step toward providing end-to-end productivity tools for small businesses. Users could access a range of tools to help them run their businesses, completely free of charge and with zero technical overhead, while Google gained even greater insight into what business owners needed. Google was positioning itself to become indispensable to small-business owners.

Google didn’t want to just help people promote their businesses. Google wanted to be the platform from which people ran their businesses from start to finish.

Google wasted little time leveraging its new tools to expand further into the productivity space. In October 2006, Google adapted Apps for Your Domain into a new product aimed at educational institutions, Google Apps for Education. Similar to Apps for Your Domain, Apps for Education allowed schools and universities to use Gmail, Calendar, and other tools with their own branding.

Unlike Apps for Your Domain, which had clear commercial potential from the outset, Apps for Education was among the first of several experiments that Google embarked upon to learn more about new potential markets for its products. Google was smart to target schools with its emerging suite of products. Not only was Apps for Education completely free of charge for qualifying academic institutions, it was specifically designed to be integrated with schools’ existing email and administrative systems. The free pricing and ease of installation were irresistible to overworked administrators who had been laboring with aging systems for years.

Later, when Google restructured its pricing, Apps for Education would be practically indispensable. And, most importantly, Google was priming its future user base—school children—to use G Suite apps by introducing them to its tools early. Google’s entrance into the education sector was also a valuable learning experience for the company. It provided Google with firsthand experience of catering to institutional organizations with legacy software systems and many thousands of users, a process it could later optimize and replicate when it began aggressively targeting the enterprise.

By 2006, Microsoft had been the top dog in the productivity space for more than a decade. However, despite the strength of its Office product, which had more than 400 million users as of 2006, Microsoft had grown complacent. Much of Office’s growth in the 2000s had been driven by the fact that it was bundled with many installations of Microsoft’s Windows OS rather than sales of individual licenses. Although Microsoft would unveil a raft of new features in its Office 2007 product, the company was vulnerable when Google debuted Apps for Your Domain and Apps for Education in 2006. It was a bold, confrontational move that left no doubt as to Google’s intentions to go after Microsoft’s uncontested dominance in the document and productivity space.

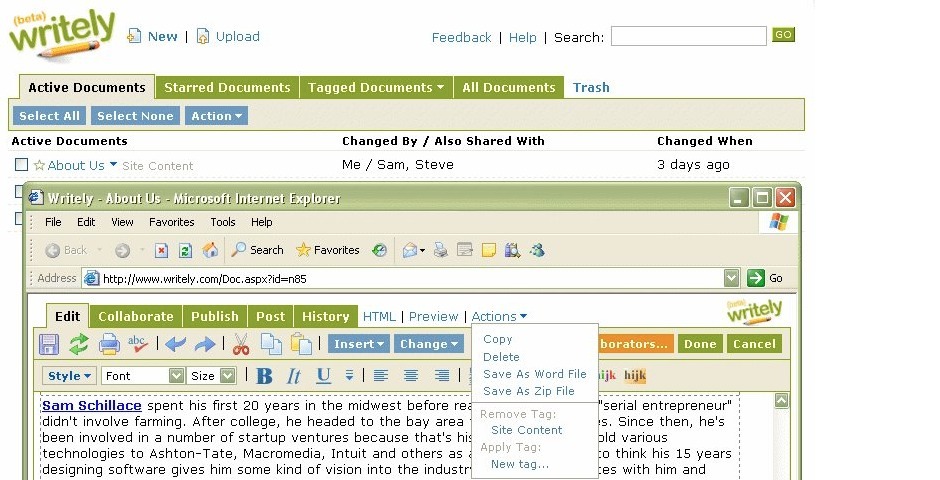

In October 2006, Google unveiled the latest additions to its Apps range of products: Docs and Spreadsheets, its word processing and spreadsheet tools. Docs was adapted from a web-based word processor known as Writely, which had been developed by the software development firm Upstartle that Google had acquired for an undisclosed sum in March 2006. This move was aimed squarely at Microsoft Word and Excel.

Writely was notable in that it was built using the then-new Ajax web development framework, which allowed for updating of web pages without the interruption of page reloads. However, the real technical challenge was adapting these tools for real-time, multi-user collaboration. Enabling multiple users to edit a single document simultaneously was a considerable technical challenge, which is one key area in which Google excelled compared to Microsoft.

Similarly, Spreadsheets was based on a tool Google had acquired in 2005, XL2Web, developed by 2Web Technologies. Shortly after acquiring XL2Web, Google launched Spreadsheets as a first-come, first-served limited-access test on Google Labs, which was later rolled out to all Google Accounts to coincide with the launch of Google Apps Premier Edition in February 2007.

Premier Edition was Google’s first step in monetizing its new productivity tools. Building on the integrations Google introduced with Apps for Education, Apps Premier Edition was initially priced at $50 per year per user. Upon the release of Premier Edition, Apps for Your Domain was rebranded as Google Apps Standard Edition, while Apps for Education was rebranded as Google Apps for Education. At that time, more than 100,000 businesses were using Apps Standard Edition. Now, Google was ready to move into the enterprise more aggressively. Household goods giant Procter & Gamble, CRM platform Salesforce, and corporate real estate network Prudential Preferred Properties were among Google’s first enterprise partners.

“Procter & Gamble Global Business Services has enrolled as a charter enterprise customer of Google Apps, a successful consumer product suite now available to enterprises. P&G will work closely with Google in shaping enterprise characteristics and requirements for these popular tools.” — Laurie Heltsley, former Director, Procter & Gamble Global Business Services

Google’s immense financial and technical resources provided the muscle it needed to compete against Microsoft. All Premier Edition users were given 10GB of individual storage, a previously unthinkable amount of space for such an inexpensive product. Premier Edition’s Service Level Agreement was similarly ambitious, guaranteeing enterprise users 99.9% uptime and 24/7 dedicated customer support.

Despite Google’s crystal-clear intentions about its desire to dominate productivity in the enterprise, the company didn’t neglect its Standard Edition suite of applications. Alongside the launch of Premier Edition, Google introduced two new products as part of Standard Edition: Google Docs and Google Spreadsheets. By this point, Google’s cloud-based tools couldn’t compete with the functionality of desktop clients such as Microsoft Office––but luckily, they didn’t need to. All Google needed was for its Apps to be faster, cheaper, and easier to use than Microsoft’s tools.

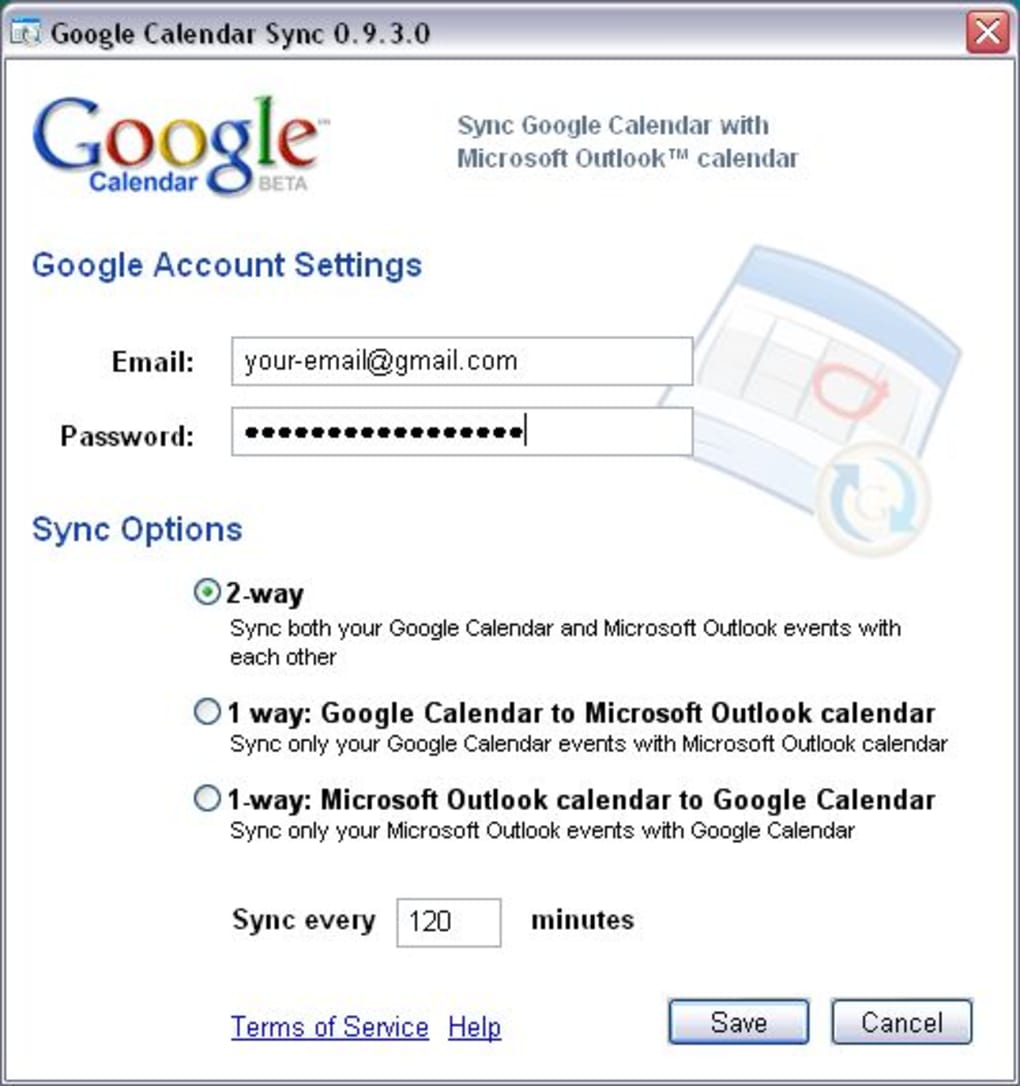

After Docs and Spreadsheets joined the rest of the Apps family, there were fewer major updates to Apps for the next year or so. Google Sites was launched in February 2008, but the next major release came over a year later when Google announced users could now sync their Premier and Education Edition applications with Microsoft Outlook. This was a huge win for Google. The company had made no secret of its desire to compete with Microsoft in its most valuable market, the enterprise. What Google had to do, however, was find a way to infiltrate companies that had been built on top of Microsoft’s products.

Integrating its Premier and Education Edition apps with Outlook was brilliant. Companies could continue to use their Outlook installations to handle corporate email without the misery of actually using the Outlook product, the UI of which had become bloated and confusing even in 2008. Without a doubt, Microsoft realized what Google was trying to do, but refusing to integrate Outlook with Google could have caused significant damage to Microsoft’s brand and perceptions of its products. With the Outlook integration, Google gained vital opportunities to insert itself into companies’ existing tech stack and prove how much easier and more productive it was to work with Google’s tools. All Microsoft got out of the deal was saving a little face and potentially losing enterprise customers.

In July 2009, Google Apps officially exited beta. By this time, Google Apps were being used by more than 1.75M businesses around the world. The primary motivation for the formal announcement was—again—Google’s desire to appeal to enterprise clients. Its tools were robust yet flexible enough to meet the needs of companies of all sizes, but Google realized that the “beta” label on many of its Apps was harming adoption at the enterprise level.

“We’ve come to appreciate that the beta tag just doesn’t fit for large enterprises that aren’t keen to run their business on software that sounds like it’s still in the trial phase. So we’ve focused our efforts on reaching our high bar for taking products out of beta, and all the applications in the Apps suite have now met that mark.” — Matthew Glotzbach, former Director, Product Management, Google Enterprise

Google had not only developed several free tools that were arguably as good as Microsoft’s paid products, but had done so very quickly. Critics and skeptics had expressed doubts about Google’s abrupt move away from desktop, but such criticisms were soon forgotten in light of Google Apps’ popularity. However, if Google really wanted to wrestle market share away from Microsoft, it had to achieve a delicate balance of developing consumer-friendly products that people wanted to use that also had the robust functionality that the enterprise clients Google wanted to attract expected.

2010-2014: More Experiments, More Products, More Infrastructure

In just a few short years, Google had radically diversified its business to move beyond search into the emerging cloud-based productivity space. It had secured several important deals with large enterprise companies such as Procter & Gamble, which had been valuable learning opportunities for a company still exploring the enterprise SaaS sector. Google would spend much of the next several years experimenting and refining its approach, including a lateral move into the hardware space, the rebranding of its ever-expanding range of tools, and the launch of several brand-new products.

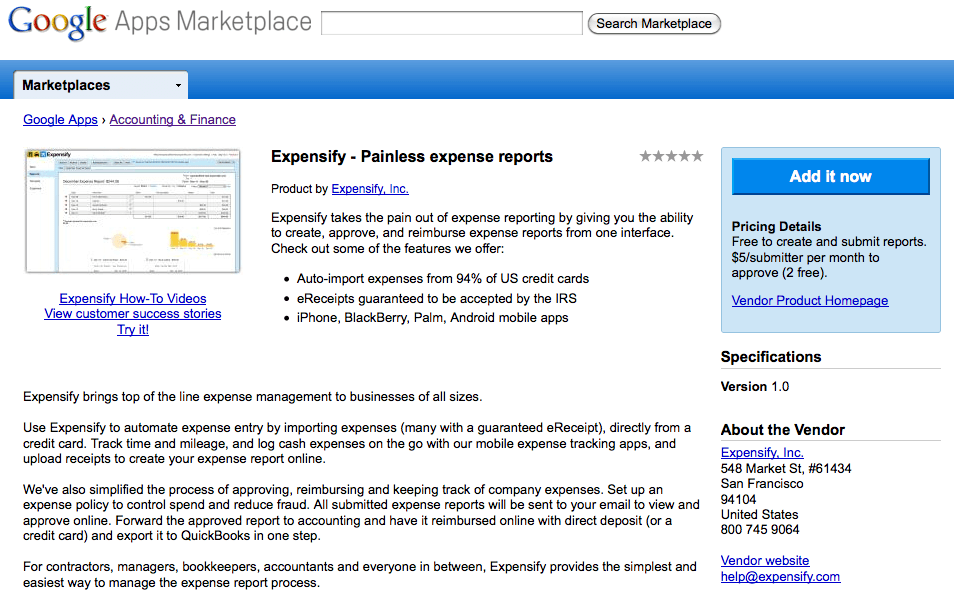

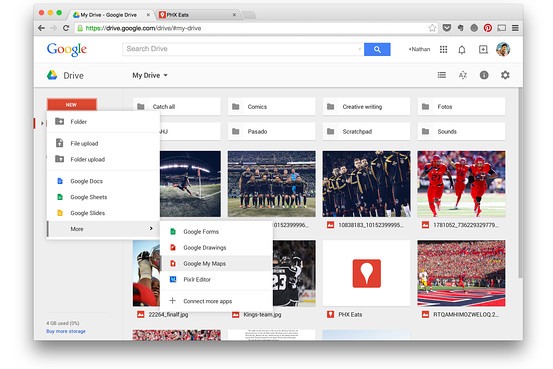

By the end of Q1 2010, more than 2 million companies around the world were relying on Google Apps to run their businesses. Google capitalized on this momentum by launching the Google Apps Marketplace in March of 2010. Similar in appearance to the Google Play Store for Android apps that launched in 2008, the Google Apps Marketplace offered businesses a range of cloud-based productivity tools created by third-party app developers. Apps from more than 50 developers were available at launch, many of which offered businesses even more utility, such as Intuit’s Online Payroll and a software development suite from Atlassian that allowed software engineers to move seamlessly between Google Apps and JIRA.

Google Apps Marketplace was a win-win for everybody. Google was able to offer companies an even greater range of tools and applications to help them run their businesses without having to develop these tools in-house. Companies could now handle even more routine tasks in the cloud for free or very inexpensively without being forced to pay thousands of dollars for custom application deployments across their organizations. Third-party developers got to market their apps and tools to a significantly bigger market and had the added benefit of being affiliated with Google.

“We’ve found that when businesses begin to experience the benefits of cloud computing, they want more. We’re often asked when we’ll offer a wider variety of business applications—from accounting and project management to travel planning and human resources management. Today, we’re making it easier for these users and software providers to do business in the cloud with a new online store for integrated business applications.”

By the summer of 2010, Google had been working with dozens of the world’s largest enterprise firms and had learned a great deal about the unique needs of these organizations. The company applied this newfound knowledge to its next experimental endeavor in July 2010 with the launch of Google Apps for Government.

What was particularly smart about Google Apps for Government wasn’t necessarily the considerable revenue potential of offering cloud-based IT services to state and federal government agencies—the immense volume of data that working with the federal government offered was what Google really wanted. Even in 2010, Google had more raw computing power than virtually every single corporate entity on the planet. By offering its services as the IT and cloud-computing provider of the U.S. government, Google would not only gain unprecedented access to a wealth of invaluable demographic, financial, and policy data, but also make itself fundamentally indispensable to one of the largest institutional organizations in the world.

However, as strategic as the launch of Google Apps for Government was, it did create some problems for Google. Not least of which was the increasingly confusing range of various collections of apps under the Google Apps umbrella. To streamline and simplify its expanding range of service tiers, Google Apps Premier Edition was rebranded as Google Apps for Business, and Google Apps Standard Edition was rebranded as Google Apps.

As necessary as the rebrand was, it actually served two purposes. First, it simplified the product tiers to make it more obvious as to who the target audience for each tier actually was. Second, it laid the foundation for the next phase of Google’s strategy to monetize its suite of tools, which would begin in April 2011 with restrictions to the maximum number of users at a company that could sign up for a free Google Apps account to just 10 (reduced from 50) and the introduction of monthly billing for its Business plans.

However, the rebranding of Google Apps in November 2010 was overshadowed by one of Google’s single biggest product announcements to date. Its Chrome operating system.

Chrome signaled a major shift in Google’s thinking as a company. By the end of 2010, AdWords had generated more than $28 billion in annual revenue for Google, a 180% increase from the $10 billion in revenue Google earned from AdWords when Apps first launched in 2006. However, despite the phenomenal revenues that Google’s advertising business was driving, some investors had expressed concern that Google was too heavily dependent on advertising as a revenue stream. The announcement of Chrome OS revealed Google’s intentions to align itself much more closely with its leading competitors, Microsoft and Apple, both of which had robust hardware businesses.

Unfortunately for Google, it had waited far too long to get into the hardware game.

By the time Chrome OS was announced in 2010, Google’s Chrome web browser had been available for two years and was installed on approximately 8% of PCs worldwide. Chrome OS was an extension of the Chrome browser. It looked the same, felt the same, and technically speaking, arguably was the same, with some minor differences in architecture. Chrome the web browser had laid the groundwork that Chrome the operating system would continue, namely making the notion of local hard-disk storage obsolete. Google had helped businesses migrate their productivity to the cloud—now it wanted to migrate the contents of everybody’s hard drives to the cloud, too.

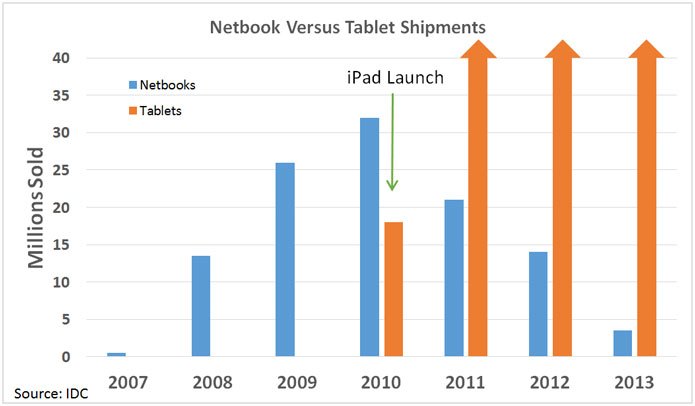

What Google had failed to account for, however, was the incredible pace with which the consumer IT hardware market would change in the interim. When Google first began developing its Chrome browser in 2008, the netbook market appeared to be the next major paradigm shift in home computing. They were lightweight enough to be practical and highly portable, and seemed ideal for working with cloud-based tools like Google Apps. However, as Google developed its Chrome OS between 2008 and 2010, Apple single-handedly altered the landscape of the hardware market with the release of the iPad. By the time Chrome OS was unveiled to the world, netbook sales had been devastated by the iPad’s runaway sales––a trend that would continue for the next several years. Correlation doesn’t always equal causation, of course, but the impact was significant.

In April 2012, the company announced the launch of Google Drive, its online storage service. The launch of Drive was critically important for Google. Not only was Drive integral to the future of its Apps products, it was an aggressive play by Google to branch out into a competitive space. By the time Google released Drive, Dropbox already had more than 50 million users, and both Apple and Microsoft were offering cloud-storage products.

Drive was a strong product right out of the gate and built on the successful strategy Google had used with Gmail. Drive was available on PC, Mac, Android, and iOS from launch, and Google Apps users were given 5GB of storage for free. This put Drive on equal footing with Apple’s iCloud, which also offered 5GB of free storage at that time, and offered more than twice the 2GB of storage offered by Dropbox. However, it fell short of the 7GB offered by Microsoft’s SkyDrive service (which was renamed to OneDrive in 2013 following a lawsuit filed by British broadcaster BSkyB). Power users could pay more for additional storage space, starting at $4 per month for an additional 20GB of space, and could purchase up to 16TB, an incredible amount of space at that time. Drive also boasted robust security features, with strong file encryption as standard and optional two-step verification.

Committed to fighting a losing battle, Google announced the release of the first Chromebook netbook computer in November 2012. The Chromebook was popular with die-hard Google loyalists and casual users, but would ultimately fail to become the hardware success story Google had hoped for. The experience of using the Chromebook was solid. The machines were fast, with a cold boot taking just 15 seconds or less. Chrome OS’s UI was sleek and elegant, and felt highly responsive to use. The first Google Chromebook, the Cr-48, also featured some interesting design choices, such as shortcut keys instead of traditional function keys and a dedicated search key that replaced the Caps Lock key.

However, it wasn’t enough. It looked and felt too much like a conventional laptop, and the machine’s dependency on the cloud meant that Chromebooks had limited offline utility. However, Google’s biggest mistake wasn’t designing the wrong kind of hardware—it was betting big on browsers. Google was ultimately proven right about its instincts on cloud computing and the future of SaaS products. It was dead wrong about the future of cloud computing being centered around a web browser. Despite moderately strong initial sales of the Chromebook, sales of Apple’s iPad soon outpaced Google’s netbook. While a largely failed hardware launch might have doomed other companies, Google wasn’t deterred. On the contrary, the development and launch of the Chromebook was another valuable lesson learned.

Google continued to refine its monetization strategy around Apps. In December 2012, Google announced that all businesses, regardless of size, would now have to use Google Apps for Business if they wanted to access Google’s cloud-based tools. Until that point, companies had the option of using Google Apps Standard Edition.

“When we launched the premium business version we kept our free, basic version as well. Both businesses and individuals signed up for this version, but time has shown that in practice, the experience isn’t quite right for either group.” — Clay Bavor, former Director of Product Management, Google Apps

Connecting its many different tools and services to a single Google account was brilliant. Google knew it would face steep competition with its cloud-based storage product. However, Gmail was by far the best free web-based email client available. By June 2012, Gmail had more than 425 million monthly active users—all of which also had a Google Account. By connecting Gmail—and, by extension, users’ Google Accounts—to all its other cloud-based services, Google’s competitive differentiator became the ease with which Google users could move between various products. This frictionless, seamless connectivity was Google’s ace in the hole.

Even if Apple, Dropbox, and Microsoft upped their free storage limits, users still had to manually move between Google and third-party services, which was relatively easy—just not as easy as moving from one Google product to another. The connectivity of Google’s search functionality within Drive, Apps, and even Gmail was another compelling reason for Google users to use Google’s products over competing offerings.

To further streamline its increasing range of cloud-based services, Google applied a global storage limit for paid Google Accounts in May 2013. Until that point, Drive storage was limited to 5GB, whereas Gmail was limited to 25GB. After the change, premium subscribers could spread out their 30GB total storage limit across Gmail and Google Drive however they saw fit. Similar storage limit restructuring was also applied to Google’s basic accounts, giving free users more control over how their 15GB of storage was allocated. It was a comparatively small change, but the elimination of the arbitrary separation of storage limits was another positive step for free and premium users alike.

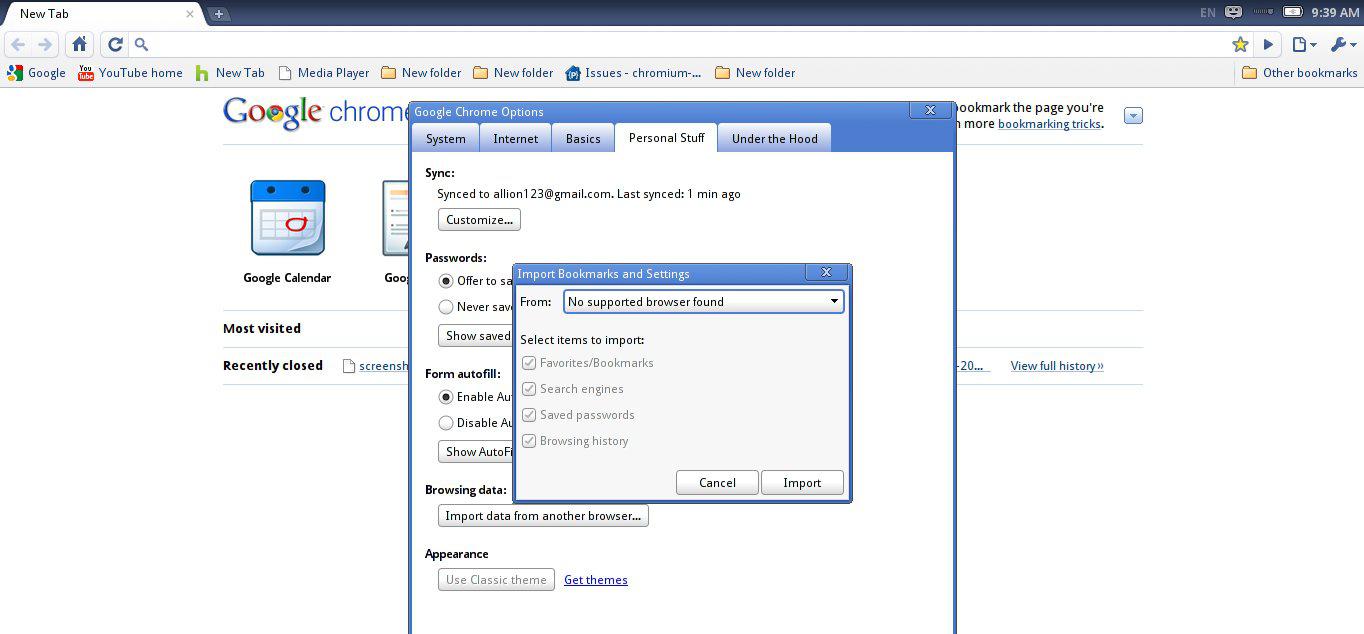

A few months later in September 2013, Google finally released desktop versions of its Apps. This announcement coincided with the fifth anniversary of its Chrome browser, and were made available for both Windows and Mac OS users, provided users of those platforms also used Google’s Chrome browser.

The decision to support desktop versions of its Apps served several purposes for Google:

- It made Apps a much more attractive proposition for business users who were looking for an alternative to Microsoft Office but did not yet completely trust cloud-based productivity tools

- It encouraged adoption of both Apps and Chrome on PC and Mac platforms, while also driving adoption of Google’s Chrome browser on those operating systems

- It broadened the potential reach of Google Apps significantly

- It appealed to third-party software developers who could write software for the web as opposed to developing multiple versions of the same tools for different computing environments

For all the advantages that the desktop release of Apps offered, it was also a tacit admission that Google’s vision of an online-only future was a little optimistic—at least in terms of how soon we’d be reminiscing about the bygone age of physical hard drives.

In June 2014, Google Apps underwent the second of its three major rebrands with the launch of Google Apps Unlimited. Essentially the same product as Google Apps for Business, Google Apps Unlimited came with all the features of Apps for Business, with the exception that users would now receive unlimited storage space for just $10 per user, per month. The only real restriction was that companies with just four users or fewer were capped at 1TB of storage per user. Companies couldn’t selectively choose which users were upgraded to Unlimited, however; either every user upgraded, or nobody did.

Between 2010 and 2014, Google managed to make a dent in Microsoft’s market share of the productivity vertical. Just not as big a dent as Google would have liked. To succeed in its ambitions to compete with Microsoft, Google had to think bigger than just browser-based apps. To do so, Google would do what it does best which is to optimize its products constantly and methodically. In the coming years, such improvements would come in the form of smarter apps built upon Google’s vast reams of user data and its cutting-edge machine learning technology.

2015-Present: Smart Apps, Smarter Tech

By 2015, G Suite was being used by millions of individuals and companies around the world. Although its Premium plans were a valuable revenue stream, Google realized that further product development would be key to winning its war against Microsoft. That’s why, from 2015 onward, Google doubled down on improving G Suite’s apps to be smarter, more efficient, and more helpful to individual users and enterprise clients alike. It began by going back to its roots by improving Gmail.

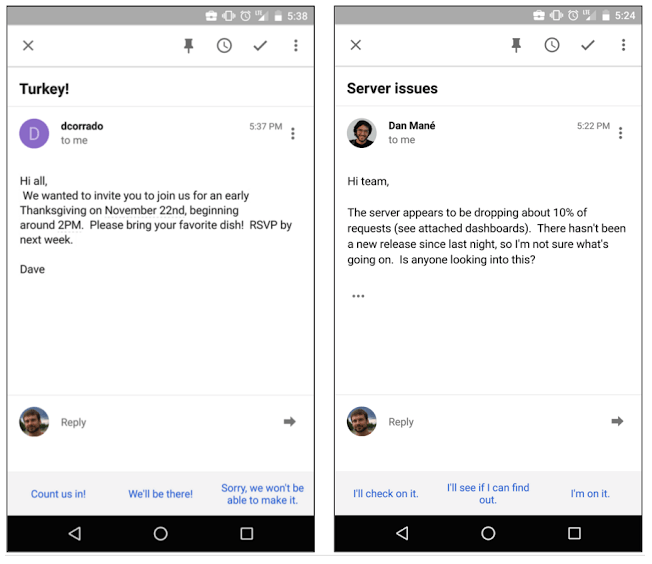

In March 2015, Google unveiled Smart Reply, one of the biggest updates to Gmail in years. Smart Reply was essentially an extension of Google Suggest, the URL completion tool that junior software engineer Kevin Gibbs had built singlehandedly on a bus way back in 2004. Smart Reply scanned users’ emails for contextual keyword clues, then offered up to three suggested responses based on the content of the email.

Smart Reply is one of those product features you’ve really got to experience firsthand. For desktop Gmail users, Smart Reply might not feel particularly revolutionary. If you’ve used Gmail on mobile, however, you’re probably already an enthusiastic Smart Replier, or have at least tried it once or twice. What’s most exciting about Smart Reply isn’t necessarily the time savings offered––though the most hardcore productivity evangelists will no doubt treasure those precious few seconds that Smart Reply saves them––but rather what Smart Reply tells us about Google’s plans.

If Google can save us minutes now, it will save us hours in the future.

Google’s productivity team kept a relatively low profile after the introduction of Smart Reply. That changed in September 2016 when Google formally announced the third and final rebrand of Apps to G Suite, a decade after the launch of Google Apps for Your Domain.

This rebrand wasn’t just necessary to minimize confusion about its various product offerings—it was the strongest indication yet of Google’s intention to aggressively pursue the enterprise cloud-based productivity market. Until that point, Google had primarily served educational institutions and startups (and, to a lesser extent, government agencies) with its business tools. This had been an invaluable learning experience for Google, particularly during its first tentative steps into the productivity market. However, colleges and startups weren’t going to cut it in terms of long term revenue or market share. As of 2015, Google held just 3% of the enterprise productivity market and had earned just shy of $400 million in annual revenue. Microsoft, on the other hand, controlled approximately 95% of the enterprise productivity space and had earnings of almost $12.7 billion.

“There’s a lot to like about Google G Suite, especially if you’re either using the free version or taking advantage of the paid version’s professional email and conferencing. But comparing it to the omnipotent Office 365 is like, to steal a simile from Stephen King, comparing a flashlight to a lighthouse.” — Eric Grevstad, PCMag columnist

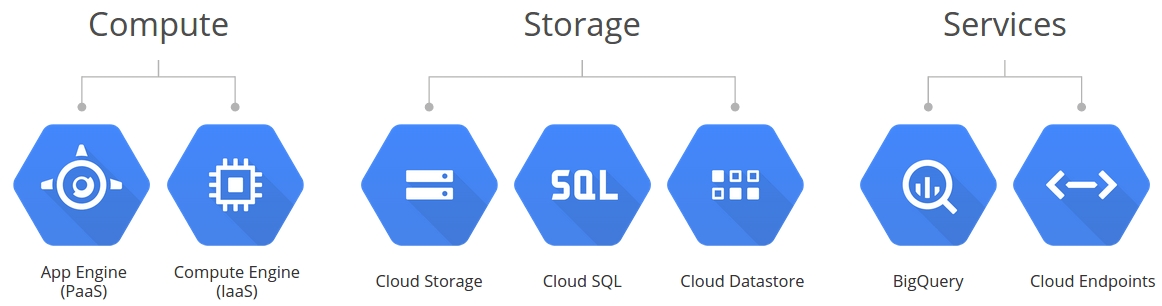

The next phase of Google’s enterprise charm offensive came a few months after the G Suite rebrand, when Google rebranded its enterprise business as Google Cloud in September 2016. As before, this rebrand was necessary to distinguish Google’s ever-increasing range of platforms and products, particularly as the company geared up to go after the world’s biggest tech companies. However, the rebrand itself wasn’t the exciting part––it was the machine learning tools that the enterprise clients Google was going after would soon be able to take advantage of.

Microsoft Office may have had a significantly larger enterprise user base and higher revenues, but Google had more raw computing power. Google’s Cloud Machine Learning product, which was made available to all businesses with the Google Cloud rebrand, allowed companies to train their own neural networks using their own data, but with Google’s computational muscle. This was Google’s competitive differentiator. It could offer productivity tools to rival Microsoft Office and the technical horsepower that could compete with Amazon Web Services and similar platforms. Combined with its cutting-edge machine learning technology, Google was poised to become a serious threat in the enterprise space.

Google’s aggressive stance soon paid off. Following the rebrand to G Suite and the introduction of new enterprise-focused tools and services, Google slowly but surely gained ground in the enterprise productivity space. By January 2017, Google had more than 3 million paying G Suite customers worldwide. Just over a year later, in February 2018, that figure had grown to more than 4 million.

Most of these users were the smaller companies and startups that had long made up the majority of G Suite’s user base. Google had, however, managed to attract a steady stream of larger corporations, including Colgate-Palmolive, Nielsen Holdings, and Verizon who were high-profile clients that contributed to the $1.3B in revenue Google earned from sales of G Suite. Every enterprise client that signed up for G Suite gave Google’s tools more credibility as a serious Office contender. Soon, companies that would have never considered relying on Google’s tools were examining G Suite’s potential with renewed curiosity.

“I have been talking to traditionally conservative companies in government, aerospace, financial services. That would not have happened two years ago.” — Jeffrey Mann, analyst, Gartner

Microsoft may have the bigger market share, but Google has one crucial advantage over its Goliath-sized competitor—mobile. Microsoft never really “got” mobile, especially with regards to Office. This was always an Achilles heel for Microsoft. Office boasted a wealth of sophisticated features that G Suite users may never get, but this doesn’t necessarily translate to how people work today. People didn’t love G Suite because of its advanced functionality. They loved it because it was simple, easy, fast, and everywhere. According to Google, almost 75% of time spent in Docs, Sheets, and Slides is collaborative. This percentage is so high because, unlike Office, G Suite is wherever people need it to be—on the mobile device in their pocket, on the tablet in their bag, or on the desktop in their office. Microsoft has invested a great deal of time, money, and effort trying to mimic this seamless, cross-platform experience. Unfortunately for Microsoft, the company still hasn’t solve this problem and caught up.

In January 2019, Google announced the launch of a new API for Docs that allows users to automate a range of routine tasks within its word-processing tool. The API was in development from April 2018, during which time several companies adapted the API for internal use-cases. Automation tool developer Zapier, for example, used the Docs API to help users create offer letters based on a range of preset templates. Netflix used it to streamline and automate its internal documentation process.

What’s really exciting about the Docs API isn’t the range of tasks users can now automate––it’s what Google will do with this technology moving forward. The Docs API is one of the clearest signals yet that Google fully intends to transform how we work by eliminating many of the burdensome, time-consuming tasks that take up so much of our time. This has the potential to be an even more profound shift in productivity compared to the initial move from desktop clients to the cloud.

If any company could come close to jeopardizing Microsoft’s dominance of the productivity space (especially in the enterprise), it is Google. Despite several missteps, Google learned a great deal about how to combine the functionality of enterprise products with the accessibility and aesthetic of consumer-focused apps. What will really set Google apart from Microsoft in the coming years will be how well it can incorporate machine learning technology to G Suite, and how it can further leverage its unrivaled computing power to help the next generation of entrepreneurs start smarter companies.

Where Could G Suite Go From Here?

Trying to predict Google’s next moves is always an exercise in creativity. That said, when it comes to G Suite, there are several likely moves Google could make. Where could G Suite go from here?

- More machine learning tech/automation. The sophistication of its machine learning tech is one of the few areas in which Google genuinely has the upper-hand over Microsoft. As such, we’re likely to see more focus on the kind of efficiencies we’ve seen with recent updates to Gmail such as Smart Reply. If Google can save us minutes per week now, they’re likely aiming to save us hours in the near future.

- More features/higher pricing for enterprise clients, more free stuff for individuals. Google cannot rest on its laurels if it hopes to continue gaining market share in either the consumer or enterprise market. It seems likely that Google will continue to develop additional features and functionality for its large enterprise clients and the pricing increases that are likely to accompany such a move. As well as offering even more free perks to individual users, such as more Drive storage space to keep pace with competitors in the consumer space such as Apple and Dropbox.

- A major acquisition to halt/preempt potential competition. Google lost out big to Microsoft by failing to acquire GitHub. Google is also at risk of further competition from its lack of a direct Slack competitor. It’s possible that Google may acquire a significant competitor like Slack (or Atlassian, for a more enterprise-friendly acquisition) rather than risk investing the time necessary to develop a competing product internally.

What Can We Learn From G Suite?

1. Never stop experimenting. Google’s internal culture of constant experimentation and risk-taking has proven to be an important driver of growth at Google as well as a constant learning process for the company. Though most startup founders can’t launch a netbook “to see what happens,” there are many small experiments that startups can run.

Take a look at your product and answer the following:

- What experiments can we run now? What do we hope to learn from those experiments? How quickly can we set them up? How will we measure them?

- Google’s ambitions for its hardware projects and Chrome OS were crushed by the surprise launch and popularity of Apple’s iPad. Regardless of whether yours is a physical product or a digital service, how are you identifying potential vulnerabilities that could emerge in a rapidly changing market? What kind of risks do those threats pose to your your product?

- Google saw opportunity in Microsoft’s complacency, and capitalized upon it by making a free product that was faster and easier to use. A move that was a radical departure from its core search business back in 2004. Can you identify similar opportunities in your own industry? What might they look like?

2. Don’t be afraid to kill projects that aren’t working out. Just as Google has never been shy about trying new things and betting on projects that never took off (Google Glass, anyone?), entrepreneurs shouldn’t be afraid to “kill their darlings” and pull the plug on products and even experiments that aren’t delivering.

Think back over your product’s history so far:

- Be honest—have you ever fallen prey to the sunk-cost fallacy? If so, what would you have done differently?

- Conversely, think about a time when you canceled a project or stopped development of a new feature. What would have happened if you had allowed the experiment to proceed?

- Google has never been shy about trying new things. However, even the company’s failures have been valuable learning opportunities that the company has used to inform its future plans. When was the last time you learned something valuable from a failed initiative, and how did you apply what you learned to your future initiatives?

3. Going after larger clients is a great way to learn. In G Suite’s earliest days, the company intentionally targeted massive companies like Salesforce and Procter & Gamble, even though its enterprise offerings at that time were a little lacking. This was an immensely valuable learning experience for the G Suite team, and offered unprecedented insight into what enterprise clients need and how they work.

Think about your product, the industry you’re in, and how you’re marketing and positioning your product:

- If you could magically land your dream client or customer overnight, who would it be and what might you learn from securing their business?

- How could you prove the value of your product to a client or company? What would you have to do to make this happen?

- Let’s say you’re developing a SaaS product with a primarily B2B target market. A large, household-name brand approaches you with a wish list of three features they’d like to see in your product that would make this brand consider using your product—but you can only build one. How would you prioritize which feature to build, and what impact would this have on your growth strategy?

Heads in the Cloud

It’s been fascinating to watch Google gradually iterate on G Suite over such a lengthy period—not to mention how shrewdly it has seized precious market share from Microsoft.

G Suite might never be the Office killer-app that many believed it would be, but Google doesn’t need to beat Microsoft in order to succeed. For millions of users, G Suite overtook Office years ago. What remains to be seen is what Google will do with its increasingly popular productivity suite in the coming years and how Microsoft and hungry newcomers alike will respond.

Do you use G Suite? You can find your G Suite documents, alongside documents from other apps, in 3 clicks or less by using FYI.