Why Dropbox Wants to Be the Next Atlassian—and How It Could Do It

On Thursday, August 9th, 2007, the founders of 19 startups gathered at the now-defunct office of the Y Combinator (YC) accelerator in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They were there for Demo Day, Y Combinator’s highly-anticipated biannual startup showcase.

Only four of the 19 companies participating in Demo Day 2007 had working betas. Most companies that presented on that fateful Thursday didn’t make it, but some did. Online commenting platform Disqus was among the companies that showcased their products that day. Cloud-based distributed database company, Cloudant, was another.

One company in particular, however, would exceed the expectations of Y Combinator’s demanding panel of judges, later becoming one of Silicon Valley’s earliest “unicorn” companies and the first Y Combinator company to go public.

That company was Dropbox.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Dropbox almost single-handedly created the cloud-based storage market as we know it. Dropbox was the first truly cross-platform, cloud-based storage service. Dropbox promised to solve a deceptively complex problem––giving people a way to store any file, from any device, in a single online directory––in a simple, elegant way.

Dropbox didn’t just change how we store things in the cloud. It was one of the first consumer-focused, cloud-based services. It changed how we think about online storage. Not too shabby for a product that Steve Jobs famously dismissed as “a feature, not a product.”

However, after years of positioning itself as a near-invisible background process, Dropbox has evolved to become a more active, engaging application with a true UI––a change not everyone has embraced.

Here are some things we’ll learn as we explore Dropbox’s history:

- How Dropbox leveraged existing behaviors in a new way that solved a genuine problem

- How Dropbox’s double-referral program drove massive growth after other growth strategies failed

- Why Dropbox’s fixation with the “prosumer” market ultimately led the brand astray

- How Dropbox is reinventing itself to be like Atlassian to stay competitive

When Dropbox founder Drew Houston presented at Y Combinator’s Demo Day in 2007, he barely had a functional prototype. What he had was an incredible idea––and that idea was enough to make everyone in attendance sit up and take notice.

Dropbox 2007-2011: A Lean, Mean Referral Machine

In December 2006, Drew Houston was on a bus to New York City from his home in Boston, where he was studying at MIT. Houston had originally planned to get some coding done on his laptop during the four-hour drive.

Unfortunately for Houston, he forgot the USB thumb drive that stored all his work. With his files in Boston and no connectivity on the bus, Houston decided to use his time productively. He began hacking together a rudimentary file-sharing application that would allow him to synchronize his files via the web.

That application would become Dropbox.

“I worked on multiple desktops and a laptop, and could never remember to keep my USB drive with me… My home desktop’s power supply literally exploded one day, killing one of my hard drives, and I had no backups.

I tried everything… but each product inevitably suffered problems with Internet latency, large files, bugs, or just made me think too much.”

— Drew Houston, cofounder, Dropbox

Despite still being enrolled at MIT, Houston hoped to gain a place at the Y Combinator accelerator in San Francisco to develop his idea. The problem was that when Houston applied to YC, he didn’t have a Minimum Viable Product. He barely had a prototype. What he did have was a four-minute video showing how Dropbox worked. Houston uploaded the video to a Hacker News thread and submitted it as part of his application.

Just four months after hacking together his prototype on the bus from Boston to New York, Houston flew across the country to San Francisco. He wanted to personally show off his demo to YC cofounder Paul Graham in the hope of securing a place. However, Graham strongly advised Houston to find a cofounder before his admission interview.

With just two weeks until the deadline, Houston began frantically searching for a partner and collaborator. He would find it in Arash Ferdowsi, a computer science major at MIT. After a two-hour conversation about his plans, Houston knew Ferdowsi was the cofounder he’d been searching for. With just six months remaining until his graduation, Ferdowsi dropped out of MIT to work with Houston.

Cofounders Drew Houston (center left) and Arash Ferdowsi (center right).

Source: TechCrunch, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Houston and Ferdowsi presented the most rudimentary of prototypes at Demo Day 2007. The “product” worked, but it was really more of a concept than a functional product at that point.

During the presentation, Paul Graham suggested a novel idea to demonstrate how Dropbox worked––by asking Houston to delete his presentation from his laptop and restore it from a saved version in the cloud.

Graham’s suggestion was unorthodox. But Houston and Ferdowsi rose to the challenge––and so did their product.

Dropbox––which was still called Drop Box at that time––clearly had a lot of potential. It also had a lot of competition. The enterprise-focused Box had been in operation for almost two years. Online backup service Carbonite had already been on the market for 18 months. Recovery service CrashPlan had been around for a couple of months. Microsoft launched its OneDrive product on Aug. 1, 2007, just one week before Houston and Ferdowsi presented their demo in Cambridge. Then there was Mozy, Freepository, Strongspace, Xdrive, OmniDrive––there was certainly no shortage of companies and products trying to solve cross-platform virtual storage.

“Dropbox impressed investors in Boston. It just didn’t impress them enough to write a check…Boston investors had an entire week before any Silicon Valley investors saw Dropbox, and not one of them made a move. I think the party line was that ‘the space was too crowded.’”

— Jessica Livingston, cofounder, Y Combinator

Dropbox was available as both an OS X and Windows client. In terms of the product itself, the earliest version of Dropbox functioned similarly to the version-control software used by programmers.

Users first had to install Dropbox on their local machine. A directory was created on a user’s hard drive during installation. Files saved within that directory were then synced in the cloud and monitored for further changes. Every time those files were updated, Dropbox would sync. Users could also see a changelog in which every major revision of a file was visible and could revert to older versions if needed, just like in most version-control systems. Initially, users were restricted to a rather generous 2GB of storage space.

In September 2007, less than a month after presenting at Demo Day, Houston and Ferdowsi raised a $1.2 million seed round led by Sequoia Capital. Shortly afterward, Dropbox launched in private beta. Users had to be invited to try the service and invite codes quickly became highly sought-after.

Despite being flush with Sequoia cash, Dropbox faced two immediate challenges. The first was the necessity of installing Dropbox on a user’s local machine. Asking users to install a third-party tool and give it permission to manage private files in the cloud was a big ask. This was especially true of techies––Dropbox’s primary audience––many of whom were much more conscious of potential privacy concerns than the average user. Generally, though, the app received a warm reception as word of Dropbox spread online.

The second challenge was how to actually acquire the product’s initial users. Between the two of them, Houston and Ferdowsi had years of technical experience. What they didn’t have was any real marketing or business development expertise. To publicize the private beta of their app, Houston and Ferdowsi created a short video highlighting what Dropbox could do. The two founders posted this video to social bookmarking site Digg.

The video was wildly popular. In just over 24 hours, more than 75,000 people signed up for Dropbox. Houston and Ferdowsi had expected a waitlist of 15,000 users at most.

Initially, neither Houston nor Ferdowsi had planned a limited-access private beta. In fact, they’d assumed they would do what many young companies do. They thought they’d launch an AdWords campaign or hire someone to handle marketing. When they tried the DIY approach, the two founders realized just how little they knew about successfully marketing a software product. The two founders were spending roughly $300 to acquire a single lead via paid channels.

The problem wasn’t necessarily the product or the positioning around it. The problem was that most people simply didn’t realize they needed the product to begin with. Many people were frustrated by emailing files back and forth or relying on external flash drives. Despite this, most people weren’t actively looking for a cloud-based storage service even though there were practically dozens to choose from.

“That’s what you’re supposed to do: hire a marketing guy, buy Google AdWords. We sucked at it.” — Drew Houston, cofounder, Dropbox

Rather than admit defeat, Houston and Ferdowsi devised a brilliant strategy to leverage interest in Dropbox as a growth vector. Beyond the 2GB of core storage space given to each Dropbox account, new users would receive an additional 250MB of space for every person they referred. The more people a user referred to the service, the more space they received. To this day, around 25% of new Dropbox users are referrals.

However, while Houston and Ferdowsi were able to successfully devise a low-cost way to attract new users, they only did so because they had to. The two founders only resorted to more creative approaches out of necessity. If they couldn’t come up with an alternative to paid search, their business probably wouldn’t have survived.

In September 2008, almost exactly one year after its launch, Dropbox emerged from its private beta. One month later, Dropbox raised an additional $6 million as part of its Series A round, led by Sequoia Capital. This marked the beginning of a period of rapid, constant growth. This was also the point at which Dropbox introduced tiered pricing. Freemium users were still given 2GB of storage. Now, users could subscribe for 50GB of space for $9.99 per month or $99.99 per year.

Source: Dropbox

Over the coming months, Dropbox attracted new users at an amazing pace. The promise of additional storage space for referring friends had been an incredible growth engine for the product. By September 2009, Dropbox had more than two million users. The launch of Dropbox’s iPhone app that same month drove even further growth. Just two months later, Dropbox had more than three million users. A few months after Dropbox released its iOS app, it launched its Android counterpart in March 2010. Growth was strong, and people loved the service.

In just a few short years, Dropbox had gone from a barely functional prototype to one of the most popular software utilities on the market. Dropbox would soon begin raising funds as quickly as it was onboarding new users, attracting hundreds of millions of dollars in venture funding. The company would put its newfound riches to use by acquiring a number of startups––an acquisition spree that called the founders’ vision for their company into question.

Dropbox 2011-2015: Money, Money, Money

By 2011, Dropbox had more than 50 million users. In August, the company raised $250 million as part of its Series B round led by Index Ventures, giving Dropbox a valuation of $4 billion. More than 45 million people relied on Dropbox to access their files in the cloud. The company would soon embark upon a series of acquisitions that appeared to reveal Dropbox’s intentions to become a platform around consumer-focused internet services. These acquisitions included iOS email service Mailbox and photo-sharing service Carousel. However, unlike Google, Dropbox lacked a native platform upon which to build this ecosystem. Given the difficulty of monetizing typically free services such as email and photo-sharing, Dropbox would soon pivot away from the consumer to focus on attracting business users and teams.

Until 2012, Dropbox’s journey had been relatively smooth. User growth was strong, and the app was incredibly popular. Dropbox seemed unstoppable––until a security vulnerability revealed that any Dropbox account could be accessed by anybody, without a password, for around four hours in August 2012. A flaw in the code of an update to Dropbox’s authentication servers was determined to be the cause. Security breaches like this have become commonplace today. But to Houston, it was a major wake-up call. Houston wrote an apology to affected users. He even included his personal cell number.

Dropbox began 2013 by giving both its Android and iOS apps an overhaul. Little was added in terms of functionality, but the apps received a fresh new look and a range of smaller improvements.

Source: Dropbox

The company’s biggest moment of 2013 came in March when it acquired iOS email service Mailbox for $100 million. At first, Dropbox’s intentions for Mailbox were unclear. As part of the announcement about the acquisition, Dropbox confirmed that Mailbox would be preserved as a standalone product separate from Dropbox. The company also confirmed it was interested in applying Mailbox’s technology to improve how Dropbox handled the storage and updating of email attachments.

What was really remarkable about the Mailbox acquisition is that it gave Dropbox a product that was designed to be used via an actual interface. Aside from being Dropbox’s single largest acquisition to date, the Mailbox deal was arguably one of the most important turning points for the entire product. It was the first time Dropbox had entertained the idea of deviating from its original core value proposition of sharing and syncing files across computers.

For a company with a valuation of $4 billion, a handful of acquisitions may not arouse much interest, let alone skepticism. However, Mailbox was just the latest in a series of acquisitions that raised more than a few eyebrows across the Valley. Dropbox acquired personal music streaming service Audiogalaxy for an undisclosed sum in 2012. Less than a week later, Dropbox bought aggregate photo-sharing service Snapjoy in another undisclosed deal.

Some of these deals, such as the Mailbox acquisition, made sense. But some, like Audiogalaxy, seemed more like impulse purchases than strategic acquisitions. Carousel, for example, was a cool product––but it wasn’t a business product. Carousel is arguably the best example of how Dropbox’s obsession with the “prosumer” market led the brand off-course. Dropbox was hooked on appealing to that prosumer market during this period. Although the motivation for this obsession was understandable––converting individual users into paying customers––the execution had been handled poorly.

After acquiring Mailbox, Dropbox went relatively quiet for the next few months. The company’s next major move was the release of its Datastore and Drop-Ins APIs in July 2013. By making it easier for developers to access and work with user data, Dropbox hoped to encourage the development of third-party apps and plugins that would expand the product’s core functionality. The Datastore API, in particular, was significant in that it allowed developers to store users’ contacts, to-do lists, and other data across multiple devices and platforms without relying on multiple APIs.

Dropbox’s next big change of 2013 came in November when the company unveiled Dropbox for Business. The company had made no secret of its plans to appeal to enterprise clients in the past. Dropbox for Business was the clearest indication of those intentions to date. It didn’t add a great deal in terms of functionality. However, it did allow users to keep their personal files and professional work separate, thanks to a tabbed interface.

Source: Dropbox

In the coming months, Dropbox just kept getting bigger. In January 2014, the company raised $350 million as part of its Series C round led by BlackRock Capital. This latest round gave the company an eye-watering valuation of $10 billion. Shortly after raising its Series C, Dropbox finally hired its first COO, Dennis Woodside, who had served as Motorola Mobility’s CEO until its acquisition by Google.

In April 2014, Dropbox relaunched photo-sharing service Carousel. The app was supposed to be a combination of Dropbox’s core cloud-storage service and a social photo-sharing app. Users could upload images or videos to their Dropbox, which could then be accessed via Carousel. Users had the option to view galleries of uploaded images by day, week, month, year, or even on a per-event basis.

Carousel was certainly fun, but it didn’t add much to Dropbox as a product. Put another way, it was a cool feature––but not a $100 million feature. Some people thought that Carousel was a hint at what we could expect from Dropbox in the future. Others, however, saw Carousel for what it was––a confusing addition to a strong product that made little sense. Would some users enjoy using Carousel? Absolutely. Did the inclusion of Carousel make Dropbox significantly more useful to personal or business users? Not at all.

Having gone on something of an acquisition spree during this period, Dropbox kept a relatively lower profile for the next year or so. After securing an additional $500 million in debt financing in April 2014, the company laid low until it announced the appointment of Vanessa Wittman as Dropbox’s CFO in February 2015.

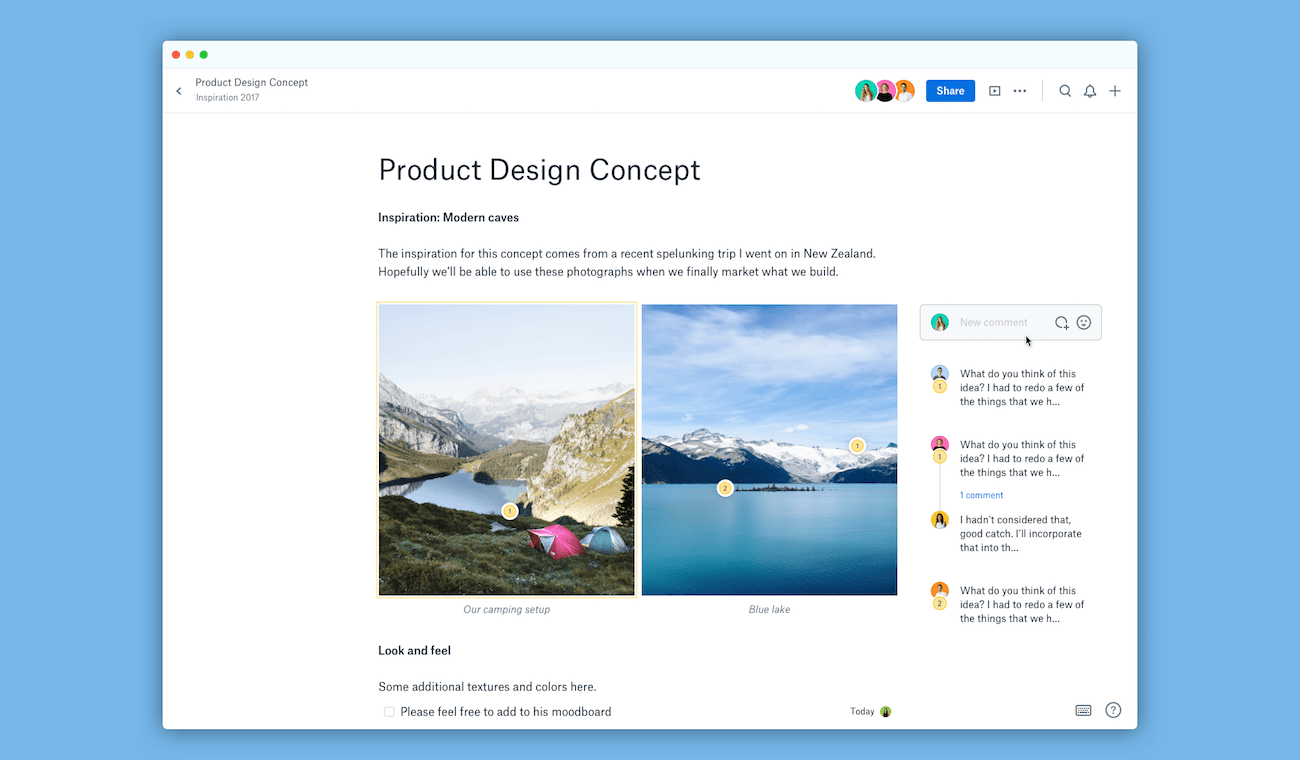

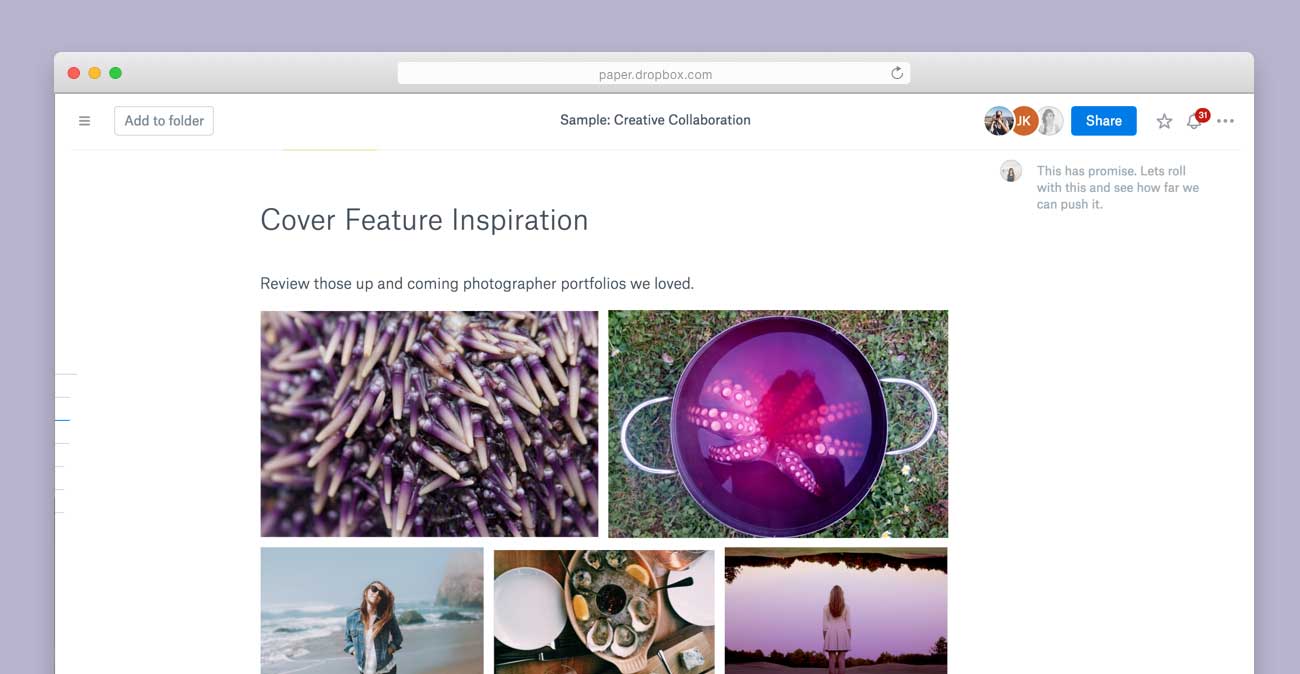

The company’s next strategic move was the release of Dropbox Paper in October 2015. Unlike Mailbox and Carousel, which Dropbox wholly acquired, Paper was the result of the internal development of Hackpad, a collaborative document-editing tool that Dropbox acquired in 2014.

Source: Dropbox

By this point, Dropbox was certainly no stranger to acquiring other software products. But Paper was different. First, it was the only acquisition Dropbox had really bothered to develop internally. Second, it was another vital step away from Dropbox’s commoditized cloud-storage business and a step toward a broader suite of productivity tools the company could use as leverage to make the product more appealing to teams in business environments. Of course, it helped that Paper was a genuinely strong product with solid collaboration features that could realistically compete against Google Docs and Microsoft Office.

Image gallery in Dropbox Paper. Source: Dropbox

Dropbox’s preoccupation with acquiring companies during this period had done little to dampen growth. Dropbox was becoming more ubiquitous with each passing day. The product had eclipsed 200 million users and had seen strong growth in its paid subscribers. Dropbox for Business had been a small but necessary step toward pursuing the enterprise more aggressively––an idea Dropbox was about to double down on.

Dropbox 2015-2019: From Identity Crises to the Biggest IPO Since Snapchat

Dropbox ended 2015 in an incredibly strong position. The product had more than 400 million users and almost 150,000 paid subscribers. The company itself was valued at $4 billion and had a war chest of tens of millions. Growth was strong. However, despite being in an enviable state of financial health, Dropbox would soon cast doubt on the founders’ vision for the future of the company. Dropbox would soon shutter two of its acquired products, Mailbox and Carousel, prompting some to question what Dropbox wanted to be and where the company was headed.

In November 2015, Dropbox unveiled its Enterprise product. In terms of the product itself, Dropbox Enterprise wasn’t particularly interesting. It offered everything you’d expect from an enterprise-focused software utility: scalable deployment tools and permissions controls for administrators, domain analytics, unlimited API access, and advanced security options, among other features.

What was interesting about Dropbox Enterprise is that it put Dropbox––a product with a traditionally strong focus on the consumer––into direct competition with the older and more established Box, which had long been an enterprise-focused product. Dropbox may have had the higher valuation, but Box had a 10-year head start.

Dropbox’s perceived competition with Box has been a source of confusion for many years. The two products shared obvious similarities. However, such comparisons have never made much sense. Dropbox wants to be the next Atlassian, not the next Box. For starters, the multiples on Atlassian as a business are much higher; Atlassian was worth more than $26 billion in 2019. More importantly, Atlassian is a company that caters almost exclusively to enterprise clients and has a diverse range of products.

Dropbox’s abrupt shift toward the enterprise felt like less of a strategic lateral move into an adjacent market and more of a knee-jerk response to investor pressure. To some extent, this may have been true. The consumer market could only sustain so much growth before additional revenue streams became necessary. But expanding into the already well-served enterprise space was still a bold move, even for a company with Dropbox’s resources.

The launch of its enterprise product should have been the start of a bright and prosperous year for Dropbox. However, shortly after Dropbox Enterprise was unveiled, the company began to run into serious problems.

In February 2016, Dropbox announced it would be permanently shutting down both Mailbox and Carousel.

“Building new products is about learning as much as it’s about making. It’s also about tough choices. Over the past few months, we’ve increased our team’s focus on collaboration and simplifying the way people work together. In light of that, we’ve made the difficult decision to shut down Carousel and Mailbox.” — Dropbox

In some ways, the closure of Mailbox and Carousel wasn’t at all surprising. Many companies acquire other products only to shutter them shortly afterward. But Dropbox’s acquisition of Mailbox and Carousel never felt like particularly good fits for Dropbox as a product or a brand. Successfully implementing functionality from both products into Dropbox may have made the core Dropbox product more useful. But this functionality certainly wasn’t necessary nor something most users particularly wanted.

Dropbox claimed the closure of Mailbox and Carousel would help the company “create even better experiences.” However, the rationale for the two products’ termination was called into question in March 2016 when the company began cutting back on employee perks to save money.

In a company-wide email sent that month, Dropbox’s executive team informed employees that a number of benefits had been or would soon be eliminated. These cuts included suspension of the company’s free shuttle service in San Francisco, the cancellation of its laundry service for gym members, and restrictions to the company’s dining policies. Dropbox estimated it was spending up to $38 million per year on employee perks.

Source: TechCrunch, CC by 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

To some, Dropbox was merely exercising a little frugality after many years of lavish spending. To others, the cuts in perks was a sign of a company in trouble. Despite the apparent strength of its financials, Dropbox was far from alone in its mission to cut costs. Many new and established startups alike were looking for ways to increase profitability. Some had begun to argue that the culture surrounding venture capital in the Valley had overvalued too many companies for too long, making a sudden contraction inevitable.

Perhaps sensing the need to get in front of rumors about the company’s financial health, Dropbox went on the offensive in June 2016. Speaking at the Bloomberg Technology Conference in San Francisco, Houston said his company was focused on “building and recruiting” and was in no hurry to go public. He also claimed Dropbox had no need to raise additional funding at that time and said that the tech sector was entering a “post-unicorn era,” echoing broader sentiments about the venture capital landscape.

“In these boom times, you get really disconnected from the fundamentals. Then the market corrects, you have a shift, where you go from a focus on growth at all costs. You have to keep an eye on your costs. Expenses that start small become big.” — Drew Houston, cofounder

For the next six months or so, Dropbox went quiet. When it emerged, it was to boast about its run rate, which Houston claimed was $1 billion. By this point, Dropbox had more than 500 million users and 200,000 paid subscribers. For all the talk of how the company was in no hurry to IPO, it certainly appeared as though Houston was laying the groundwork to do just that.

That same month, Dropbox Paper officially exited beta. Dropbox also announced Smart Sync, which made synchronization of users’ files and directories faster. However, Smart Sync did more than just speed up how quickly Dropbox files synced.

For corporate users, Smart Sync essentially transformed a company’s Dropbox account into a navigable file system, much like it were a networked drive. This made navigating between Dropbox directories and the rest of a user’s file system seamless.

Smart Sync also virtualized users’ files themselves by eliminating the need for physical space on a user’s hard drive. With Smart Sync, users could now access all files––those stored locally and those saved to the cloud––as if they were physically located on a user’s hard drive. Users could also specify which files and directories should be saved locally and which should be synced in the cloud.

Despite the lengths to which Houston had gone to assure investors of his company’s financial independence, Dropbox took out a $600 million debt financing round led by JP Morgan in March 2017. This brought the total sum Dropbox owed the banks to $1.1 billion. Even as the company shouldered more debt, it denied it was doing so in preparation to go public.

In October 2017, Dropbox unveiled its new redesign, the most significant in the company’s ten-year history. Virtually every aspect of the product and wider Dropbox brand was tweaked. For starters, the product’s logo and typeface got a fresh coat of paint. The old box icon was replaced by “a collection of surfaces to show that Dropbox is an open platform, and a place for creation.” The company also introduced Dropbox Design as part of the rebrand, where the company publishes articles on its design philosophy and approach to product development.

Dropbox finished 2017 by hiring Donald Blair, former CFO of Nike, as the company’s CFO. Blair’s credentials were bulletproof. During his sixteen-year tenure with the global footwear brand, Nike’s revenues had more than tripled and the company’s market cap had increased eightfold. Investors welcomed the move and were happy that such a seasoned veteran was watching over Dropbox’s finances. Blair’s appointment also telegraphed Dropbox’s intentions to go public––which it finally did on March 23, 2018.

Shares in Dropbox had been expected to reach between $18-20 per share. When the NASDAQ’s opening bell rang that morning, Dropbox’s stock opened at $29 per share, rising 50% to a high of more than $31. By the close of trading that day, Dropbox’s stock closed at $28.42, an increase of more than 35%.

Dropbox’s strong IPO wasn’t just a relief for the company’s investors. It was a relief for the entire venture capital industry. After years of dire warnings of inflated valuations, Dropbox had pulled off the single biggest tech IPO since Snapchat went public in March 2017.

Maybe unicorns really did exist after all.

“The strong performance of the Dropbox IPO may open the door for more technology unicorns to IPO throughout the rest of 2018. If investors had bought Dropbox stock within the last six months, they’d be up over 75%.” — Sohail Prasad, cofounder, Equidate

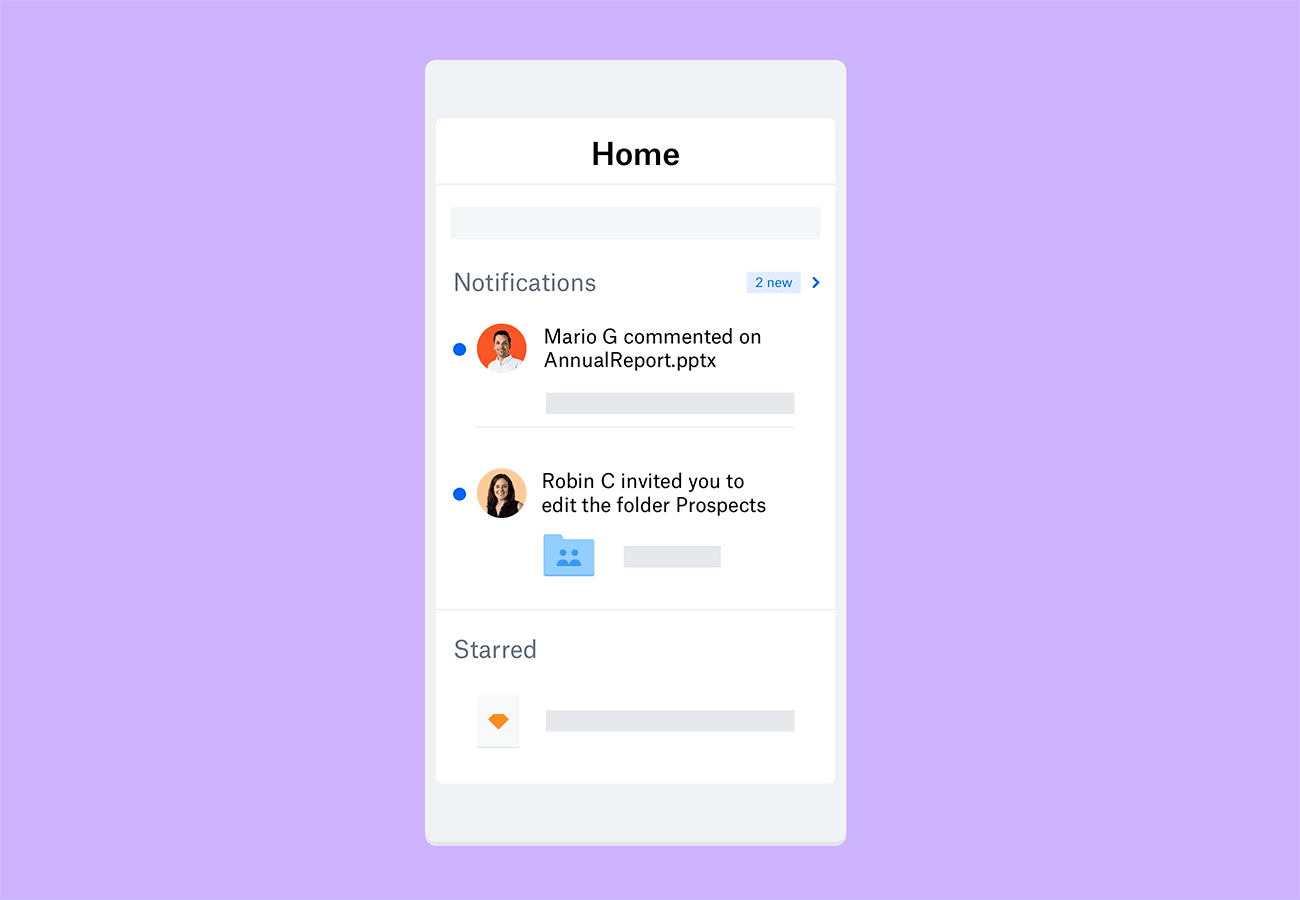

Dropbox’s next step was to make its mobile app more useful. It did so in May 2018 with the release of a series of new mobile features for Dropbox’s iOS app.

First, Dropbox introduced an Activity feed for Dropbox files on mobile. At a glance, mobile users could now see a document’s edit history, including specific line edits and shares. Dropbox Professional and Business Advanced users could also see a history of users who had viewed a particular document.

Dropbox also added a new preview design that made it easier to share documents with other users and view other users’ feedback. The Dropbox mobile app got a new Home screen that surfaced important updates for easier retrieval such as edits made to shared documents and starred items. Finally, Dropbox added drag-and-drop support, a nice quality-of-life feature that brought the mobile experience in-line with its desktop counterpart.

Source: Dropbox

The idea behind Dropbox’s improvements to its iOS app wasn’t solely to make the app itself easier to use. It was to make Dropbox as a cloud-based service more useful and seamless across multiple devices. Dropbox wanted to make work itself easier, not just make using Dropbox easier. Everything Dropbox did during this period was designed to streamline users’ overall productivity.

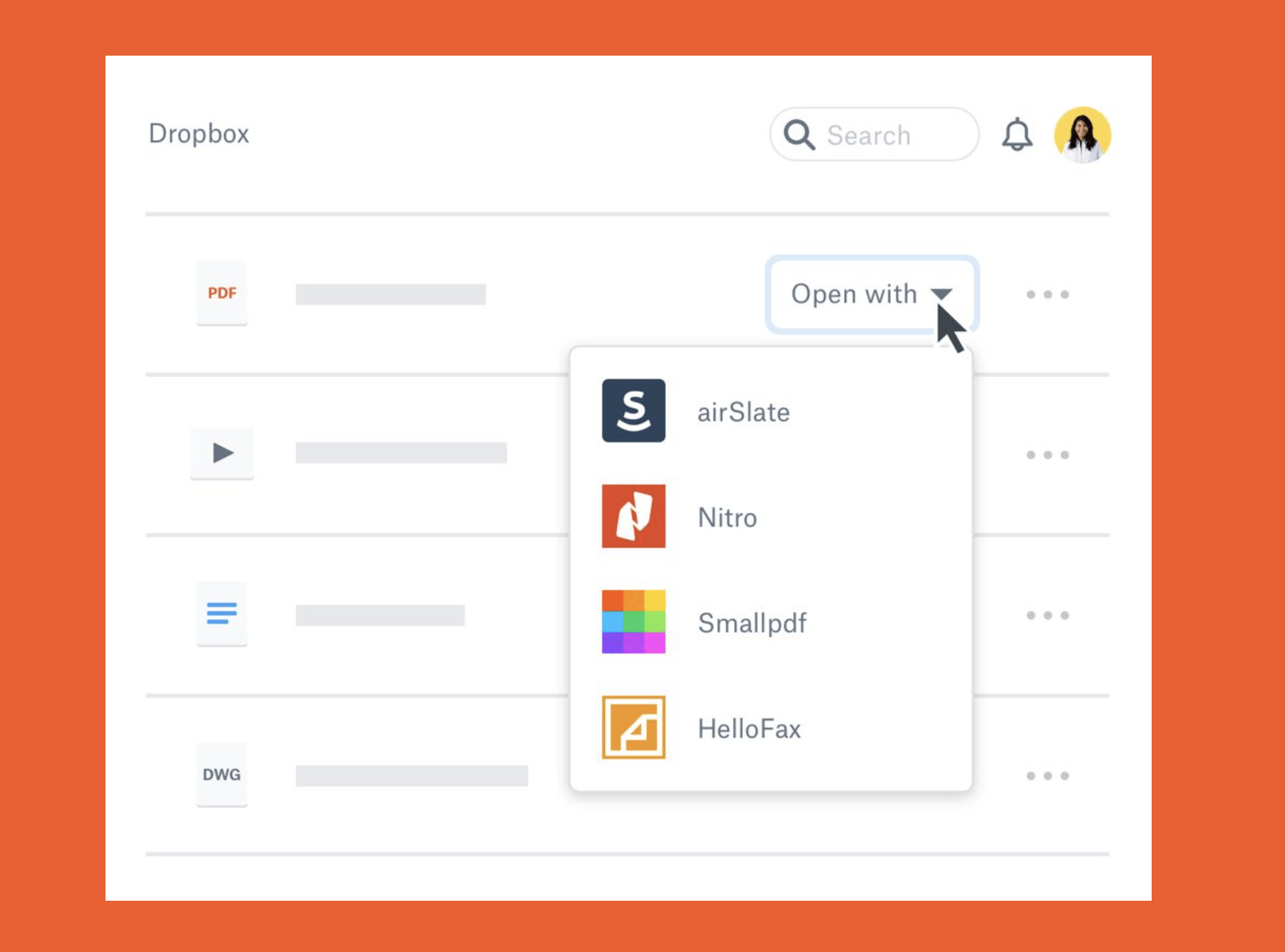

Dropbox doubled down on this commitment in November 2018 with the launch of Extensions. These third-party plugins functioned similarly to integrations and allowed users to do much more directly inside Dropbox. Accessible via a contextual menu, Dropbox Extensions allow users to open connected apps and perform certain tasks, all within Dropbox.

Initially, Extensions were available from Adobe, DocuSign, and Vimeo. For example, a Dropbox user could share a PDF of an invoice or purchase order with another Dropbox user, who could then sign the document digitally using the DocuSign extension, all without ever leaving the Dropbox app. This made Dropbox much stickier as a product. It was also another step away from the idea of Dropbox as an invisible background process and another step toward Dropbox as an active application.

Source: Dropbox

After the release of Extensions, Dropbox continued making smaller quality-of-life updates to the product. It brought automatic image uploads to Dropbox Business accounts. In January 2019, Dropbox introduced time-based commenting. This handy feature allows users to insert comments on audio and video files at specific points in media playback. This eliminated the need for users to specify times when discussing audio tracks or videos. This might not have been the biggest update, but it did show that Dropbox was just as focused on smaller incremental improvements as it was on major design overhauls and brand-new features.

2019 also brought the first of several vital purchases as Dropbox bought HelloSign for $230 million, its largest acquisition up until that point. This would set up Dropbox for a major shift as the company evolved from its original cloud-based storage product to focus even more on the enterprise. Houston welcomed the change in a statement claiming that “together, we can deliver an even better experience to Dropbox users, simplify their workflows, and expand the market we serve.”

In February 2019, Dropbox hinted at what users could expect from the company in the near future. In an optimistic, speculative blog post, the company explored the nature of work and the “state of shallow busyness” in which many workers find themselves. The post raised some valid and important points. Burnout was becoming a real problem around the world. Many workers felt trapped in unrewarding work. The proliferation of apps and cloud services––and their constant demand for our attention––was becoming a burden, not a benefit.

“Many of these specialized tools offer attractive advantages. But toggling back and forth between them all creates friction. The constant context-switching adds to the state of busyness that keeps us from focusing on our most meaningful work.

The tools are great—but juggling them all brings an opportunity cost. Which is why we’re building Dropbox as an open ecosystem that integrates deeply with popular workplace apps.” — Dropbox

The post hit all the right notes. It used lots of connective language like “we” and “our” to great effect and raised some important questions about how we work. But behind the aspirational language, Dropbox had revealed its true intentions––to become an all-in-one workspace environment similar to tools like Coda and Notion.

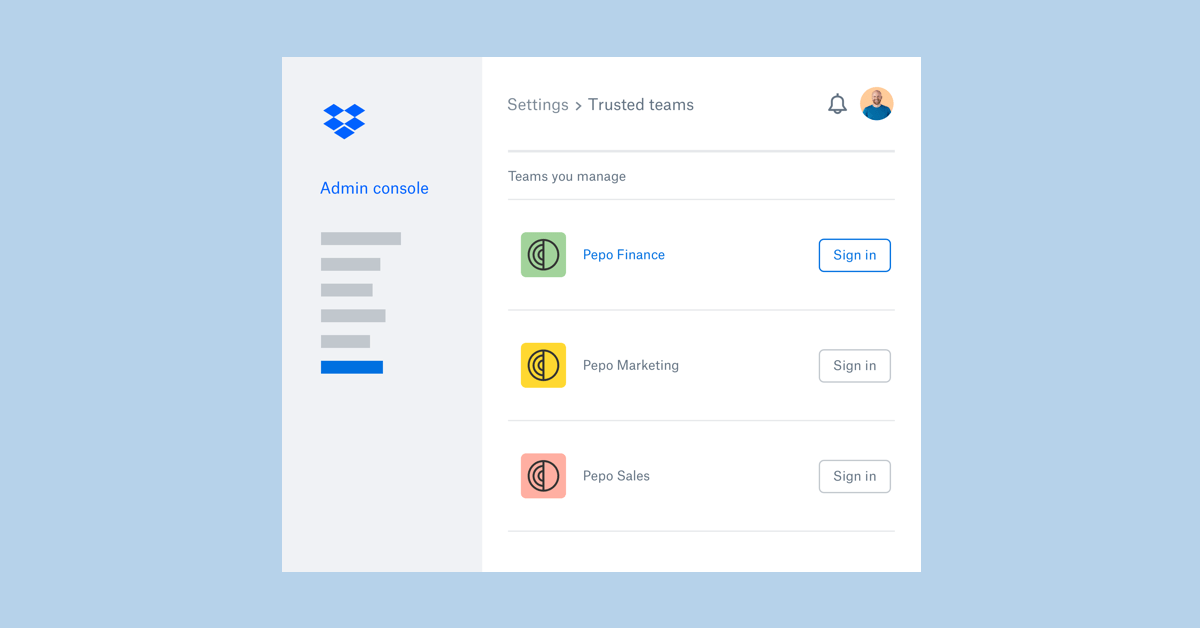

February 2019 also saw the rollout of new administration tools aimed squarely at the enterprise. The first update gave Dropbox Business team administrators the ability to manage multiple teams within the same organization. The multi-team admin features also offered much greater control over access permissions through the use of “trusted teams.”

This feature gave administrators the power to grant third parties, such as contractors, access to shared Dropbox folders and workspaces. For large corporations working with dozens of external vendors, these controls were long overdue. Dropbox’s new access management controls also made Dropbox a much more appealing proposition to enterprise clients, many of which often require complex permissions controls.

Source: Dropbox

Over the next several months, Dropbox made dozens of improvements, big and small, to the product. In March, Dropbox unveiled its newly overhauled search function. Now, desktop users could search their files and folders by clicking on the Dropbox icon in their system tray. In addition to files and folders being synchronized with a user’s computer, Dropbox’s new search function would surface everything associated with a user’s Dropbox account.

Pro and Business users got even more features, such as the ability to search for text strings within presentations and documents. The new search function also improved how results were displayed. Users could now restrict search results to specific file types, such as image files or PDFs. Best of all, Dropbox had optimized its search technologies to return results up to 65% faster than the old Dropbox.

The following month, in April 2019, Dropbox added the ability to create, save, and share Google Workspace documents directly within Dropbox. With just a couple of clicks, users could create Docs, Sheets, and Slides, all without leaving Dropbox.

This was a great example of how a product can solve problems for users and add greater value. Dropbox could have tried to force users to rely on Dropbox Paper, the workspace tool Dropbox launched in 2017. But doing so would have been a mistake. Google Workspace wasn’t going anywhere.

By early 2019, Google’s productivity suite had more than 5 million paying subscribers. Dropbox Paper had amassed a loyal and growing following in two years. But forcing users to use Paper wouldn’t have moved the needle in a meaningful way for Dropbox––nor would it have slowed G Suite’s relentless advance into the enterprise. Integrating Google Workspace with Dropbox was a much smarter play that actually benefited users and aligned with how people worked.

In May 2019, Dropbox unveiled its new content recommendation system. Powered by Dropbox’s machine-learning technologies, Dropbox’s recommendation engine helped users find the documents and files they needed quickly by analyzing users’ account activity. The more frequently a user accessed a particular file or folder, the more likely those files and folders would be surfaced by Dropbox’s recommendation system.

Dropbox’s content recommendations are another example of a small feature with a significant potential impact. Alongside content recommendations, Dropbox made a series of other updates in May that made the product much more useful to enterprise clients.

The company introduced a number of new integrations, including several automation tools such as Tray.io, Workato, and Zapier. An automated space-saving feature was added to Smart Sync. Dropbox Pro users could now add custom watermarks to images and PDFs. The available storage space for Dropbox Plus subscribers was doubled to an impressive 2 TB, and Dropbox Pro accounts were upgraded to 3 TB of storage––all for just $11.99 per user, per month.

Dropbox’s frantic pace of product development over the previous months reached its peak in June 2019 when the company unveiled an entirely new Dropbox experience.

“Today, we’re unveiling the new Dropbox. It’s the Dropbox you know and love, but better. It’s a single workspace to organize your content, connect your tools, and bring everyone together, wherever you are.” — Dropbox

The June 2019 update was the most ambitious overhaul of the product to date. Dropbox still offered cloud-based storage, but that was pretty much all the new Dropbox shared with its predecessor. Dropbox was no longer merely a cloud storage provider or a background process. It was a cross-platform all-in-one workspace, communications tool, and productivity suite with a unified UI aimed squarely at the enterprise.

What was really remarkable about the new Dropbox wasn’t that the product was taking on some of the most powerful incumbents in the cloud-based productivity space. It was how well it brought everything together. Dropbox’s integrations with Google Workspace and other industry-standard tools made the experience of working in Dropbox seamless. Moving from Dropbox to Slack to Microsoft Office was effortless and felt strongly intuitive.

The product’s machine-learning features helped users find exactly what they needed, exactly when they needed it. Dropbox’s search functionality was significantly faster and much more accurate. Everything just worked.

Unfortunately, not everybody was as excited about the new Dropbox as Dropbox was.

Among its detractors, there were two main problems with the new Dropbox:

- The roughly 20% increase in cost

- The fact that the new Dropbox wasn’t the old Dropbox

These two issues might seem like separate problems. But to many unhappy Dropbox users, they were two sides of the same coin. For years, Dropbox had positioned itself as a near-invisible background process. Now, not only had Dropbox seemingly transformed itself into an entirely different product overnight, it now cost 20% more than it used to.

Many of the most common criticisms of the new product were simple––nobody had asked for or wanted many of the new features Dropbox was so excited about. Although there was undoubtedly a subsection of users who were delighted by Dropbox’s new features, most users probably had little use for shared workspaces or third-party integrations. If they did, they were probably already using a tool like Coda or Notion.

This was always going to be the real test for Dropbox. The problem wasn’t that Dropbox’s new tools weren’t as good as competing tools or whether those tools made sense for enterprise clients. It was the simple fact that, for years, Dropbox had been a cloud-based storage service. Now, it was something else entirely that bore little resemblance to the tool people had relied on for years.

In addition to the price hike, many users weren’t swayed by Dropbox’s promises of additional storage space. One common criticism was that for casual Dropbox users, additional storage space wasn’t even necessary, never mind worth paying extra for. Many users claimed they hadn’t come close to even approaching the 1 TB storage limit. What would they do with another terabyte of storage? Another issue was that Dropbox’s brand-new features required significantly more system memory.

However, the biggest concern for some users was that Dropbox apparently installed a completely different file management application on users’ systems without their permission. Dropbox later claimed that due to “an error, some users were accidentally exposed to the new app for a short period of time. The issue has been resolved, though there might be a short lag for some users to see resolution.” Fortunately for Dropbox, the shift in the product itself largely overshadowed the legitimate privacy and security issues that accompanied the launch.

An almost overnight 180 in product focus and a micro-scandal about unauthorized installation permissions might have given some companies pause. But Dropbox wasn’t as concerned about individual users. The company had grander ambitions in the enterprise. Apparently undeterred by negative reactions on social media and determined to leverage the momentum it had established, Dropbox continued its advance on corporate America by launching its Dropbox for Salesforce Marketing Cloud app.

The Dropbox for Salesforce Marketing Cloud app allowed users to create Salesforce marketing campaigns seamlessly within Salesforce by using assets saved in Dropbox. Branding assets, contact lists, and other campaign elements could be imported and saved within Salesforce in moments. Marketers could collaborate on shared assets with external team members and contractors, even if those individuals didn’t have Salesforce access.

Until this point, Dropbox had focused primarily on broad use cases with general applications for several distinct audiences. One universal problem Dropbox hadn’t yet solved, however, was how to transfer large files. For most companies, standard FTP was the default solution. But FTP had its limitations, especially given the often stringent security and compliance requirements of enterprise clients. Email had long been another quick fix, but even Gmail could only send attachments of up to 25 MB.

Dropbox Transfer would change all that.

Transfer was Dropbox’s answer to the limitations of FTP. The tool allowed users to transfer up to 100 GB of files in just a few clicks. Like sharing items and folders in Dropbox, users could create links to bundles of files and folders. Users could then send those links to anybody, even individuals without their own Dropbox accounts, for quick and easy data transfer. Users could even control access permissions for shared items, add password protection to sensitive data, and create branded download pages.

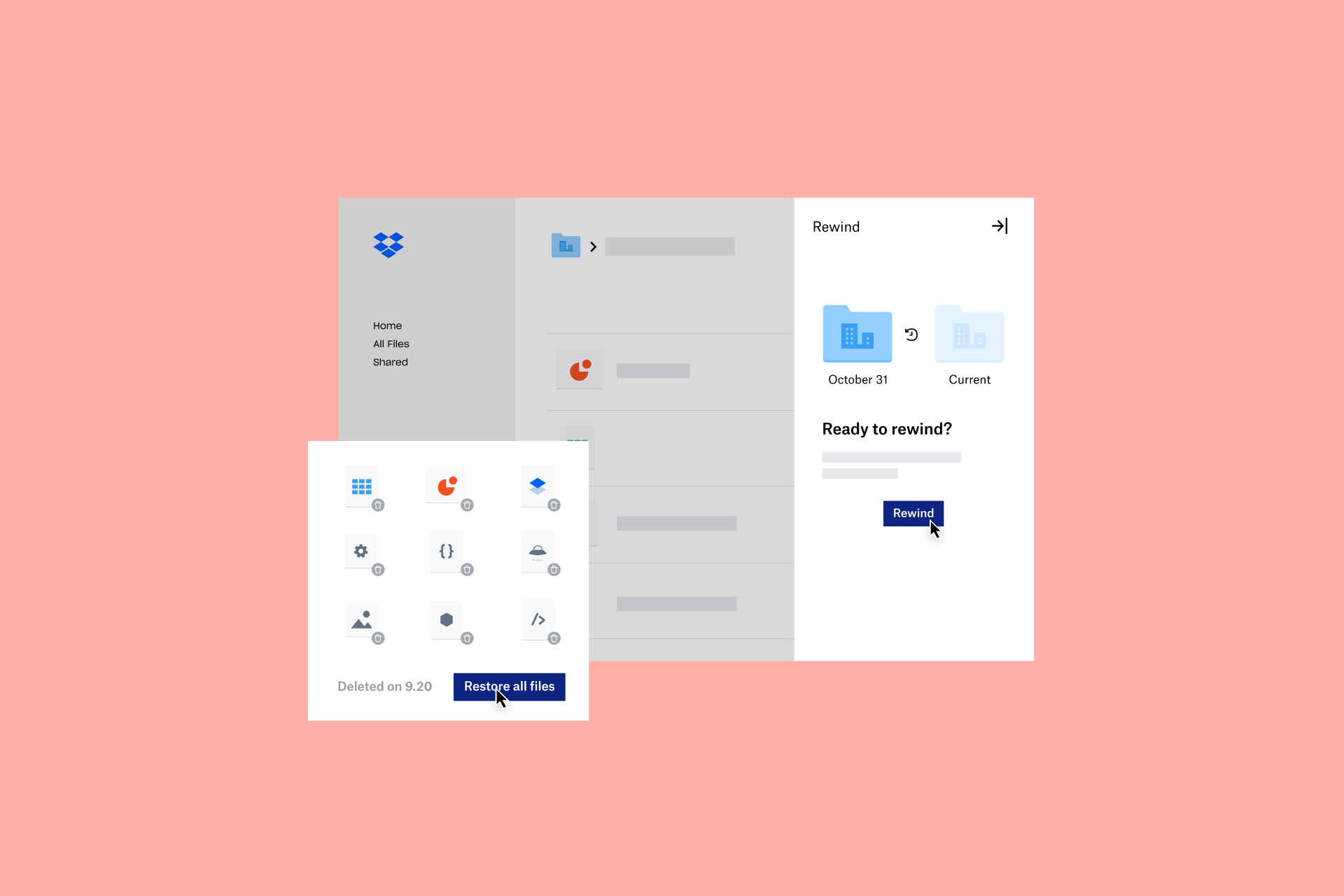

In addition to transferring large files, another stubbornly persistent problem Dropbox had yet to tackle was that of file recovery. Although there’s certainly no shortage of file-recovery tools available today, many of them are open-source or freeware. This might be fine for individuals or even small companies hoping to recover accidentally deleted files. For enterprise firms, relying on freeware data-recovery tools isn’t just impractical––it’s a considerable legal liability that’s quite literally unthinkable. That’s what made Dropbox Rewind such a smart play.

Rewind was Dropbox’s proprietary in-app file recovery system. Although Rewind could be fairly described as a file recovery system, it’s actually much closer to the full-system restore points offered by Windows’ Disk Utility and OS X’s Time Machine.

Rather than simply scanning users’ hard drives for deleted files, Rewind created dedicated backups of a user’s entire Dropbox account at periodic intervals. When discrepancies are detected, Rewind automatically restored missing files and syncs them across that user’s devices. Dropbox Plus users were limited to restoring files from the past 30 days. Dropbox Pro users could restore files from any time during the previous six months.

Source: Dropbox

Every single step Dropbox took in 2019 advanced Dropbox’s bigger mission: to help larger companies increase productivity––and profitability––without disrupting existing workflows. Many of the product’s updates didn’t just make it easier to get more done at work. They solved difficult, persistent problems that had plagued companies of all sizes for years. The fact that enterprise clients were particularly likely to benefit from Dropbox’s new features was anything but a coincidence.

Features such as Smart Sync made it much easier to integrate Dropbox into existing workflows, particularly in the workplace. However, Dropbox stumbled in how it perceived itself and what it wanted to be.

The company’s single biggest problem in 2019 was how to reconcile the product’s new direction with how it historically positioned itself. From the beginning, Dropbox set out to be a near-invisible background process.

Now, Dropbox was moving toward a product with a true UI that demanded active engagement. The irony was that neither of these two approaches was the “right” one. Both had value, and both had their advantages and disadvantages.

What Dropbox had to figure out next was how to transition from one to the other without alienating long-time users or dissuading prospective new users––all the while somehow competing with Box, Google, Microsoft, and every other tech company in the cloud-based productivity space.

Dropbox 2020-Present: Moving To a ‘Virtual-First Company’ and Reinvention

The start of 2020 was fairly quiet as Dropbox didn’t highlight any updates for January and February. Then March 2020 hit, and a global pandemic changed the world of work forever.

As offices around the world shut down and employees worried about the future, Dropbox released 11 new features and product updates in March alone, including Zoom integrations, shared file locking, and a data governance add-on. It continued its remote workforce trajectory, offering WFH virtual training courses in May 2020, and made an announcement in October that it would become a ‘Virtual First Company,’ extending its mandatory work from home policy until June 2021. It recently updated that policy to give employees even more flexibility.

“People will leave companies where they don’t have flexibility for companies that do. A company that doesn’t offer that flexibility will quickly look as archaic as a company that doesn’t have a website. —Drew Houston, cofounder

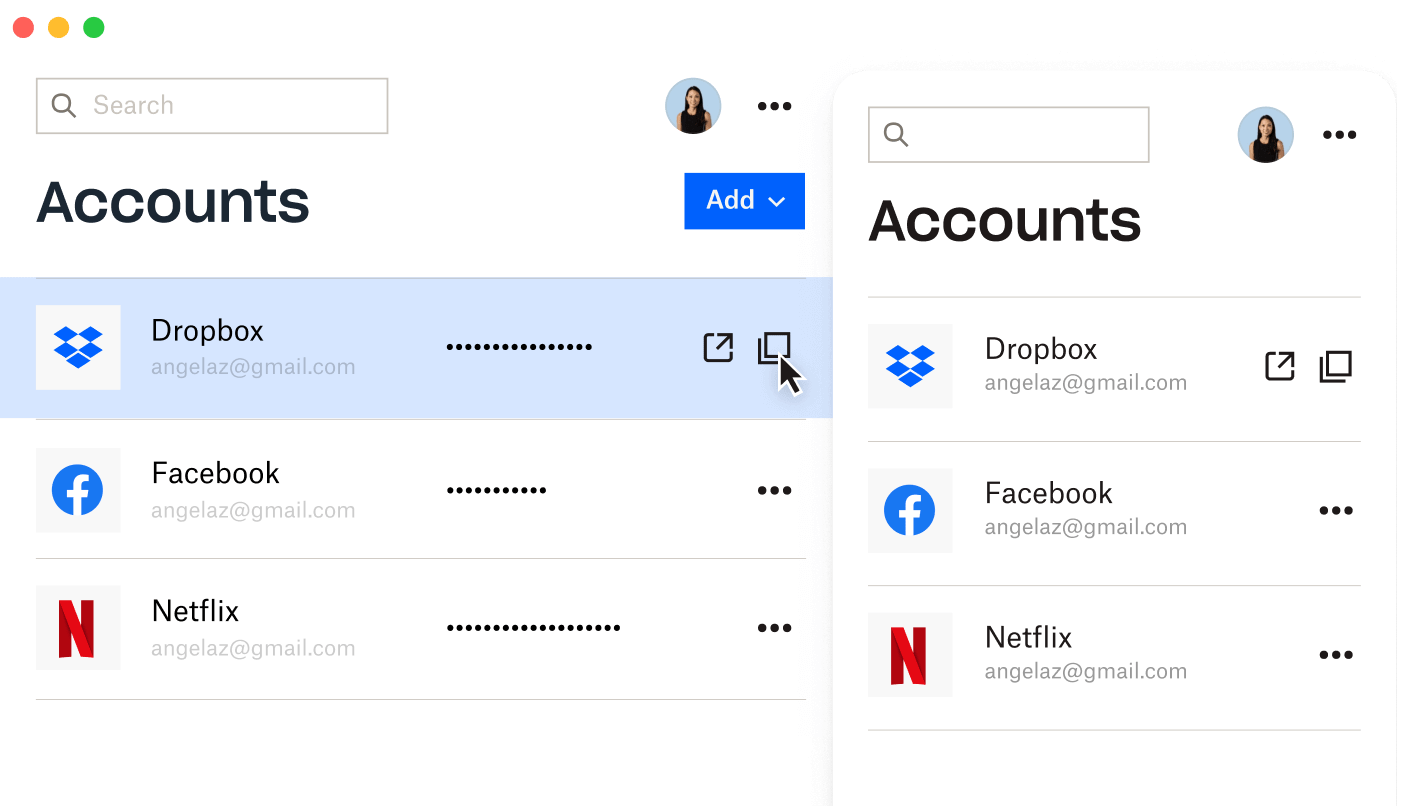

The summer of 2020 saw Dropbox releasing even more updates and features. In May, it added a host of media integration updates as well as two new features for its Trello integration. June updates included allowing users to access Dropbox files in Jira and introducing an insights dashboard called “Numbers to watch.” In July, the company highlighted newer mobile apps and features including Dropbox Scan, Dropbox Passwords, and Dropbox Vault, as its valuation went to $8.82 billion.

By August, Dropbox users received the ability to sign documents right from Dropbox, search by person, and gain support for multiple Slack workspaces, and the Dropbox Extension Platform became open to all developers.

The company continued full steam ahead in fall 2020, announcing nine new updates in September, including large file transfer of up to 250 GB, large file previews, and more control and security for file sharing. They also introduced a new integration with learning management system Canvas, allowing students and teachers to upload coursework and lectures straight from Dropbox. In October, the new Dropbox Family plan became available and Dropbox Vault was made accessible on Dropbox Professional.

Dropbox Family Plan. Source: Dropbox

Dropbox Family Plan. Source: Dropbox

November brought 11 new updates, most notable of which were better security features that included alerts and notifications, external sharing reports, and data classification. Dropbox also released its Passwords Beta for work teams, adding more color to its password management feature available to paying customers.

At the end of a tumultuous, albeit productive, year for the company, Michael Seibel, a Group Partner at Y Combinator, joined the Dropbox Board of Directors. Dropbox seemed poised to move upward. It had successfully pivoted to a ‘Virtual First Company’ and released tons of key updates and features as well as new integrations. Despite the uncertainty of the past year, things seemed to be looking up.

Then, in January 2021, Dropbox made the critical announcement that it would cut 11% of its global workforce and that Chief Operating Officer Olivia Nottebohm would leave in early February. The move affected 315 people, as CEO Drew Houston said the cuts were “painful, but necessary” in a memo sent to employees. Houston went on to iterate that the company must make hard choices to maintain its long-term health.

According to Houston, the new ‘Virtual First Policy’ meant that fewer resources were needed to support an in-office environment, so the company would scale back and redeploy those resources to “drive an ambitious product roadmap.”

Dropbox was quickly cutting costs and pursuing its 2021 goals which included “evolving the core Dropbox experience, investing in new products built for distributed work, and driving operational excellence.”

In March 2021, Dropbox made another critical acquisition when it purchased DocSend for $165 million. According to Houston, the document sharing and analytics company would help Dropbox deliver an even wider set of tools for remote work. It was a pivotal move that showed the company wanted to “strengthen its market position when it comes to online documents.”

“We’re announcing that we’re acquiring DocSend to help us deliver an even broader set of tools for remote work, and DocSend helps customers securely manage and share their business-critical documents, backed by powerful engagement analytics.” — Drew Houston, cofounder

Spring 2021 updates included enhancements to alerts and notifications, new admin roles, and external sharing reports as well as more admin controls for Dropbox-connected apps. In May, the company announced it would optimize payments with machine learning. That summer, product updates included password enhancements and file conversion, and the company rounded out August with a back-up for external drives and adding searchable tags to files and folders.

Fall 2021 brought two new remote work offerings: a visual communication tool called Capture, which was designed for teams to asynchronously share their work using screen recordings, video messages, screenshots, and gifs, and video collaboration tool Dropbox Replay.

And in October, Dropbox made another crucial acquisition when it bought Command E, an enterprise search company.

Dropbox’s commitment to its aggressive roadmap seemed to pay off financially for some stakeholders, as the company’s stock rose 10% in 2021. By February 2022, the company had joined AWS marketplace, supposedly cementing its status as an emerging leader in remote work tools and collaboration.

“Dropbox and AWS are on the leading edge of catering to the remote work experience. We support asynchronous collaboration also by connecting everybody with what they need.” —Deb McClure, Dropbox VP of sales for the Americas

Within the last few years, Dropbox has been trying to reinvent itself, both internally and with its product. It released a slew of new features in an extremely short period of time, and as a result, it can compete with a wider range of businesses. As it creates remote work tools that service both prosumers and businesses, it’s positioning itself to be a ‘Smart Workspace’ that helps organize digital content through features like automated dashboards and document conversion.

Since 2020, the company has steadily gone after feature after feature and added product offering after product offering to its platform. Dropbox doesn’t seem to be slowing down as it adds capabilities for team collaboration, content management, and secure sharing and analytics, just to name a few.

The widespread claim of 2018 that Dropbox wanted to be the next Atlassian is finally being realized. The company is taking more of a “family of brands” approach, starting with its acquisition of HelloSign in 2019, and then DocSend and Command E in 2021. These acquisitions solidified its trajectory toward becoming more enterprise-focused, while its previous acquisitions like Mailbox were more concentrated on consumers.

“While this is a broad set of features, it’s designed to expand the utility of the Dropbox family of products, and provide greater separation between the free and paid tiers, while helping Dropbox users balance work and family life from one product.” — TechCrunch

Dropbox isn’t the only company thinking this way. We talked about Notion in 2018, and it seems like more companies will take this approach in an effort to not be stagnant. Dropbox and Notion want to be used by entire organizations, rather than specific departments, as they branch out from their particular bubbles and become an integral part of companies’ workspaces.

Ultimately, it’s not where Dropbox came from but where it goes next that will really determine if it can “reinvent the software platform” as it boldly claims to investors and become a true modern workspace.

Where Could Dropbox Go From Here?

Fifteen years ago, it would have been practically unthinkable to imagine Dropbox as more than just a cloud-storage service. Now, the company’s future is as exciting as it is unpredictable. Where might Dropbox go from here?

- An even greater focus on a suite of tools for the enterprise. Having thrown its lot in with enterprise-focused productivity tools, Dropbox has to figure out its place in the broader enterprise ecosystem. However, unlike Box––which focused almost exclusively on the enterprise from the beginning––Dropbox has historically lacked the kind of institutional knowledge necessary to pitch and sell to the enterprise. If it hopes to successfully compete in the enterprise, Dropbox has to figure out exactly what the enterprise wants from it and deliver just that. Its next big step is to get usage for its updated suite of products and solidify its enterprise sales motion.

- Addressing––and solving––Dropbox’s identity crisis with Paper. Dropbox Paper is a strong product that successfully diversified Dropbox’s business beyond cloud storage. It also put Dropbox into even more direct competition with dozens of companies, including titans like Google and Microsoft. Dropbox has to decide what to do with its bet on Paper. It must figure out how to connect Paper to the core Dropbox product or leave it as a nice-to-have feature within the Dropbox suite.

- Leveraging integrations to convince people to actively use Dropbox. As a company, Dropbox bet big on its desktop app. The company also revealed some of its ambitions by the updates it made to the app, such as its integration with Google Workspace and Microsoft Office and its calendar functionality. If Dropbox wants users to actively engage with its new app, it will have to take more steps to increase the value of the product and encourage people to come back to Dropbox from other apps. And Dropbox has got the additional requirement of getting adoption across the various in-house built tools that are part of Dropbox’s suite now.

What Can We Learn from Dropbox?

Dropbox is learning how to grow beyond its core mission to provide more value to more users. What can we learn from its journey so far?

- Ship early, ship often. It’s one of the most well-worn cliches in Silicon Valley. Regardless, Dropbox exemplifies this principle better than most. Especially in the early days, Houston and Ferdowsi did whatever it took to make Dropbox the best possible product by constantly iterating on their idea.

Take a look at your product and roadmap:- Would iterating on your product faster allow you to experiment with new features or take greater risks? How could you go about accelerating your development cycles?

- Conversely, would your product benefit from slower development cycles? What might this look like?

- Think about the biggest mistake you’ve made with your product so far. Would a more iterative approach to development have avoided that mistake? If so, how––and if not, why not?

- Think carefully about distribution. How are people going to find your product? For Dropbox, traditional channels such as paid search didn’t work. This forced Houston and Ferdowsi to get creative, which in turn led to Dropbox’s wildly successful double-referral program.

Consider your product’s distribution strategy:- What’s the biggest upfront cost of finding new users for your product?

- What steps could you take over the next six months to reduce those costs?

- Even if your current distribution strategy is working well, what else could you do to raise awareness of your product and attract new users?

- Focus on real-world problems. Houston’s initial idea was so compelling because it solved a real-world problem experienced by millions of people. Even though most people didn’t realize they needed Dropbox at first, they did recognize the problem it solved.

Think about Houston’s story about his fateful bus ride from Boston to New York:- If you had to summarize what your product does by posing a hypothetical scenario to a prospective user, how would you do so? For Dropbox, this might be a question like “Ever found yourself stuck on a bus with no Wi-Fi with a deadline looming?” What would your scenario be?

- Would prospective users of your product recognize the problem your product solves, even if they didn’t realize they could benefit from your product initially? If not, how could you drive home the benefit of your product more effectively?

- How are you appealing to your prospective users where they are? Put another way, how are you connecting the benefits of your product with your distribution strategy?

From Cloud Storage to ‘Smart Workspace’

Dropbox is a great example of solving real-world problems in new ways using existing behaviors. It’s also a great case study in brand identity. Dropbox has been on a journey to figure out exactly what it wants to be. Despite the uncertainty, the product has achieved strong growth in a crowded, intensely competitive market.

The real question facing Dropbox now is how it will successfully complete its transition from what was essentially a background process to an actively engaging software product.

Tools such as Coda and Notion may be truer “workspaces” than Dropbox will ever be––but that won’t stop Dropbox from exploring its new identity and pursuing an even bigger slice of the workplace productivity pie.