From Engineers to Everybody: How Atlassian’s Confluence Conquered the Enterprise

Developing not one but two software products simultaneously just two years after establishing your company would probably sound like madness to most founders. That’s exactly what the Atlassian team did when they launched their wiki tool called Confluence back in 2004.

Confluence not only beat virtually every other wiki tool to market but also adopted a highly strategic approach to growth: targeting engineers. Atlassian already had a deep understanding of the software development community as a core market because of Jira. Atlassian leveraged that understanding to build an urgently needed second product around a highly profitable vertical it could successfully monetize before expanding to other use cases.

Atlassian’s strategy worked – Confluence has been wildly successful since launch and very popular amongst enterprise companies. And yet in spite of its popularity, feedback from customers about the product is often negative.

- How Atlassian leveraged Jira to propel the growth of Confluence.

- Why developing a wiki tool for engineers was such a smart play.

- How Confluence was able to successfully shift from an on-premise product to a SaaS product.

When Confluence launched in 2004, there were virtually no competing products available on the market. Rather than developing a consumer-focused or generalized B2B product, Atlassian did what it does best––it built a narrow, highly specialized tool for software developers using what was learned while building and growing Jira.

2004-2010: Knowledge Management, but Smarter

Australian enterprise software company Atlassian’s first product was Jira, an issue-tracking management software tool that was released in 2002, the same year Atlassian was founded.

Jira was sorely needed at that time. Prior to the release of Jira––which took its name from the word Gojira, the Japanese word for “Godzilla”––there were several bug-tracking software tools available, including Mozilla’s Bugzilla and the Free Software Foundation’s GNATS.

However, many of these tools were open-source and designed for small independent teams. Very few of the existing tools on the market were designed for or could handle the security and regulatory compliance demands of the enterprise.

Atlassian learned a great deal about developing enterprise software from building Jira. When Atlassian launched the product, it was aimed squarely at software developers working in enterprise environments.

However, as valuable a learning experience as developing Jira was, the product itself left a lot to be desired. Jira’s interface was clunky and awkward and lacked many of the conventions that people would later come to expect, such as simple drop-down menus to drag-and-drop the movement of support tickets. It also lacked a way for users to document their work or share knowledge with colleagues on other teams.

In 2004, just two years after the release of Jira, Atlassian launched Confluence.

Confluence was launched primarily as a wiki tool. Like Jira before it, Confluence was designed to appeal to software developers. At that time, software developers were still largely the de facto gatekeepers of product documentation on most product teams. Documentation was not yet seen as an interdepartmental responsibility, which meant that software developers were still producing the majority of product documentation in many companies.

“Our aim was to build an application that was built to the requirements of an enterprise knowledge management system, without losing the essential, powerful simplicity of the wiki in the process.” — Mike Cannon-Brookes, co-founder and CEO of Atlassian

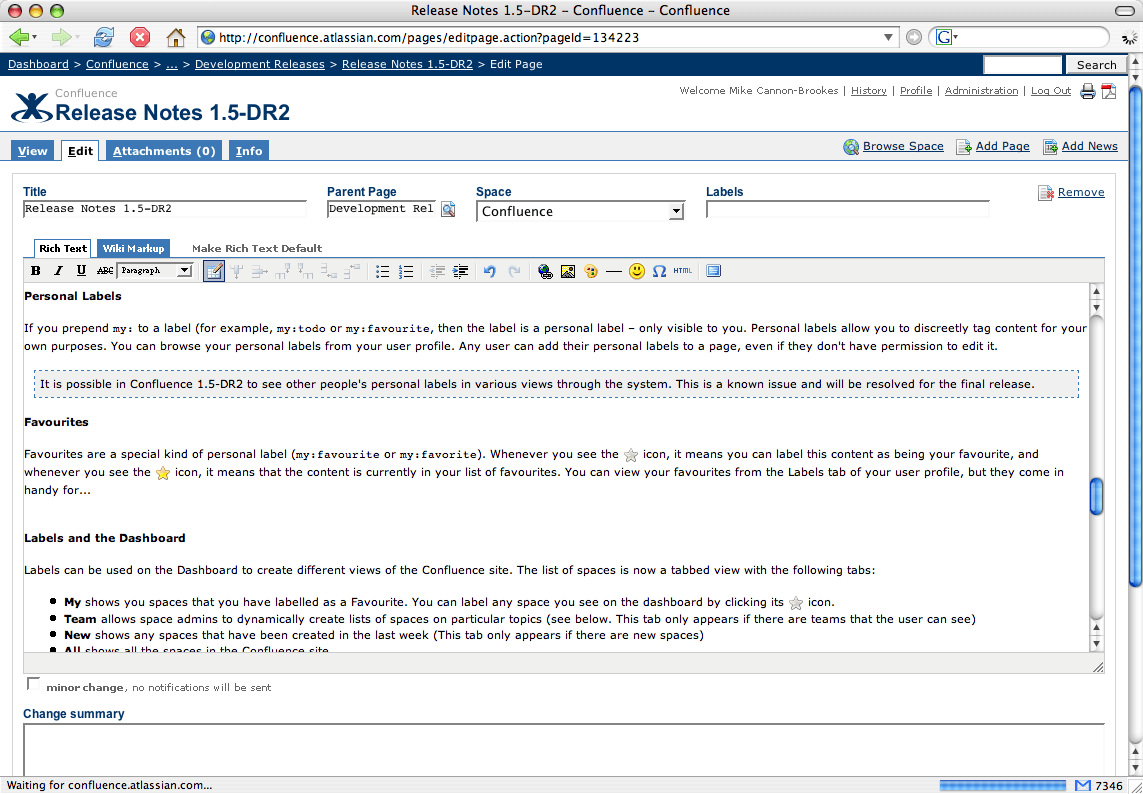

Like Jira, Confluence was powerful, if a little utilitarian in appearance. Initially, the product was web-based and was developed to support the J2EE development environment that Sun Microsystems developed for its Java programming language. This was still among the most popular and widely used development frameworks at that time, which made Confluence’s J2EE compliance predictable and necessary. When Confluence launched, it was also available as a self-hosted product. Users could evaluate the web-based product online, and download and install an on-premise version of Confluence locally. This was a very big deal. Many people did not yet trust the SaaS model, which was largely unproven in 2004, especially for a product designed for the enterprise.

Confluence itself was a wiki-editing and documentation management solution. Users could collaborate on shared documentation––though not in real time––as well as create and link internal resources. The earliest versions of Confluence relied on a WYSIWYG UI, which was popularized by WordPress in 2003.

Confluence organized everything into distinct collections of related pages called Spaces. Each Space functioned as a separate portal into a project. Each team working on a project could have its own Space, and Spaces could cross-reference files and information in another Space. For example, a Finance team could have its own Space, in which everything from employee W-2s to contractor invoices could be found. The Customer Success team might have a Space where onboarding documentation, support tickets, and feature requests would be stored.

Put another way, a Space was simply a container for all the files, documents, and assets a team needed to get their work done.

Like Jira before it, Confluence launched without a marketing strategy or any dedicated outbound sales teams. Atlassian’s plan was to rely primarily on word-of-mouth to spread the word about Confluence. Although this might sound incredibly risky for an enterprise product, it made sense at that time. For one, there were no real competitors to Jira and, by extension, Confluence. The product’s co-founders knew from experience that software engineers craved specialized tools that would make their lives easier. All they had to do was get the products in front of them.

In terms of product development, the first couple years of Confluence’s life were relatively quiet. This was partly explained by the fact that Atlassian was essentially developing two individual products simultaneously with limited resources. However, Atlassian would later become renowned for failing to address critical bugs in its software––perceptions that would cause problems for Atlassian later on.

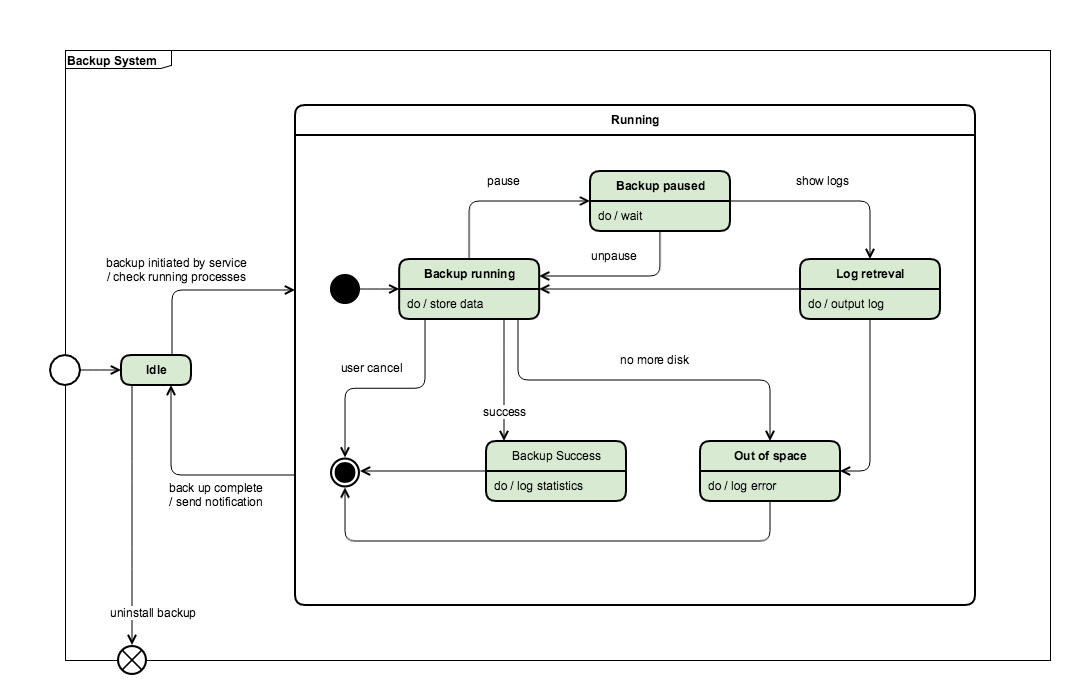

After the initial launch in 2004, the next major update to Confluence came in 2006 with the introduction of support for Gliffy Diagrams. The integration was a smart choice. Allowing people to quickly and collaboratively work on shared diagrams and flowcharts, Gliffy’s Confluence integration made it easy to create shared flowcharts, Venn diagrams, organizational charts, and other visualizations directly within Confluence.

Although the Gliffy integration did meet an existing need among customers, the integration was also Atlassian’s first real step in its growth strategy to expand beyond its core audience. Software developers were Atlassian’s bread and butter, and the company knew and understood this audience intimately. However, specifically targeting developers and engineers wouldn’t be enough to create the kind of traction in the enterprise that Atlassian wanted. The Gliffy integration was a small but vital step in making Confluence more appealing to non-technical people by offering third-party tools that developers and non-developers alike found useful.

Virtually all of Confluence’s growth during this period had been driven by word-of-mouth among the software development community. With no dedicated sales teams, Atlassian was relying solely on the reputation and potential value of the product as a sales tool. Fortunately for Atlassian, engineers loved it. This allowed Atlassian to grow Confluence’s userbase efficiently at a very low customer-acquisition cost. The company had gained a valuable head start over competing products such as Basecamp and would leverage that advantage to attract venture funding and develop new tools that would help the product reach new markets.

2010-2014: More Apps, More Collaboration, More Money

By 2010, Atlassian had built a loyal userbase of programmers and engineers with Jira and Confluence. More than 20,000 customers worldwide were documenting their projects using Confluence, including several major tech companies such as Adobe, Cisco, and Facebook.

Atlassian itself had grown to more than 220 employees in just a few short years. What Atlassian needed to do next was translate Confluence’s popularity among software engineers to a much broader cross-section of non-technical users. It would do so by developing new features with broader appeal and a greater range of use cases. Atlassian didn’t want Confluence to just be a wiki tool for engineering teams––Atlassian wanted Confluence to be the knowledge management tool for the entire enterprise.

In July 2010, Atlassian raised $60 million as part of its first funding round led by Accel Partners. The company would use the money to expand Atlassian’s product portfolio and offer a little more liquidity to Atlassian’s founders.

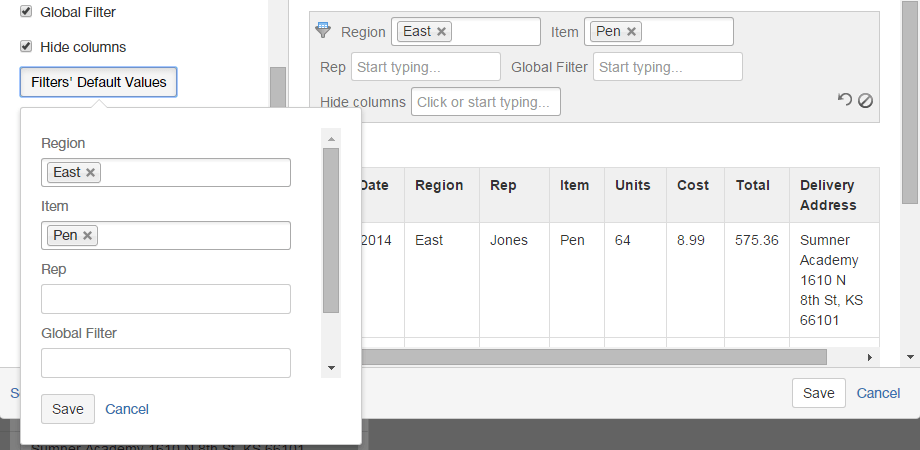

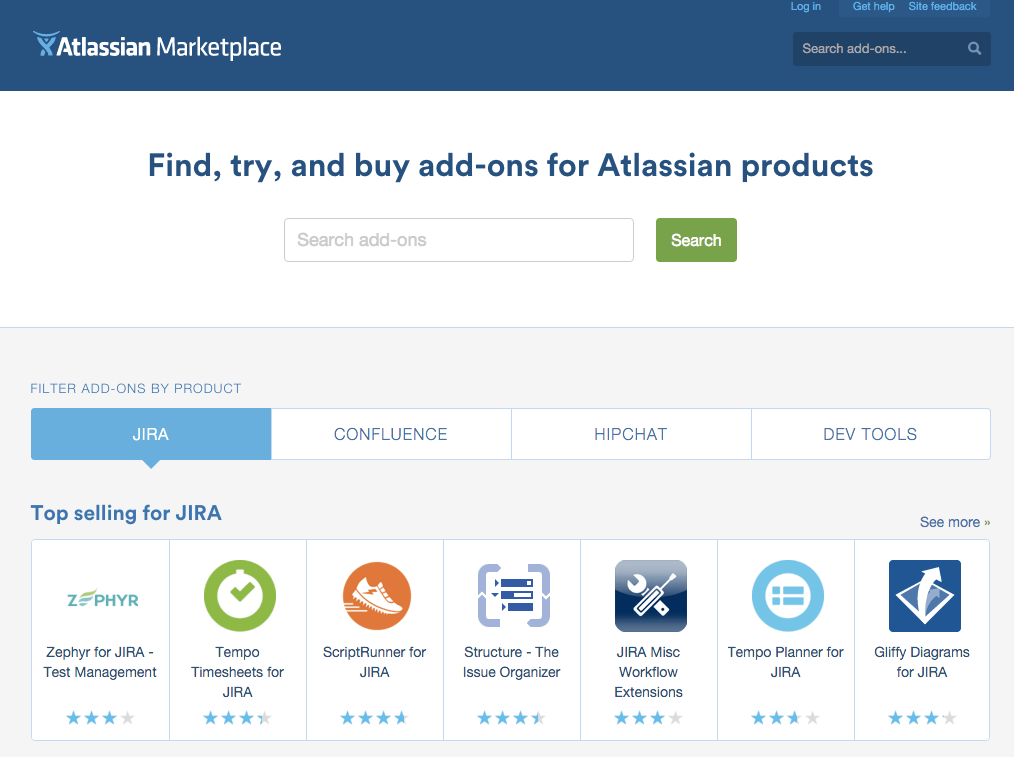

The first major update to Confluence as a product in 2010 came just a couple of months after the company’s initial funding round when Table Filters and Charts was released on the Atlassian Marketplace. Atlassian’s Marketplace is a platform similar to Google’s Chrome web store through which third-party developers can sell apps and add-ons designed to expand the functionality of various Atlassian products including Confluence.

Table Filters and Charts was one of the most significant updates to Confluence thus far. The tool allowed users to filter tabular data much more granularly than they could before. Users could filter data using drop-down and free-text filters, as well as by date and number range. The tool also supported regular expressions, which appealed to Confluence’s primarily technical userbase. Table Filters and Charts also allowed users to quickly create sparkline charts from visualizations of tabular data.

Table Filters and Charts didn’t just allow users to find and visualize data much more easily. Tables and charts created in Confluence were living documents. Changes made to the data in a source table cascaded to connected charts and visualizations throughout the product, which reduced virtually all of the friction when collaborating with teammates on shared documentation as users couldn’t accidentally delete or override one another’s changes.

For the most part, Atlassian left Confluence alone for almost a year. The company continued to support and update the product with patches and minor fixes, but the next major update wouldn’t come until March 2011 when both Confluence and Jira underwent a significant but inconspicuous overhaul.

The biggest addition was the Space Directory. Accessible from the sidebar in the main Confluence interface, this feature provided users with an overview of all the Spaces hosted in a Confluence installation. This might not have seemed like the most significant update, but it was an important step toward making Confluence friendlier to non-technical users. Atlassian made several other similar improvements to Confluence at that time, including drag-and-drop support for attaching files to project documents and improved notifications. These small quality-of-life updates all made Confluence that much easier to use and brought the feel of a consumer app to the product.

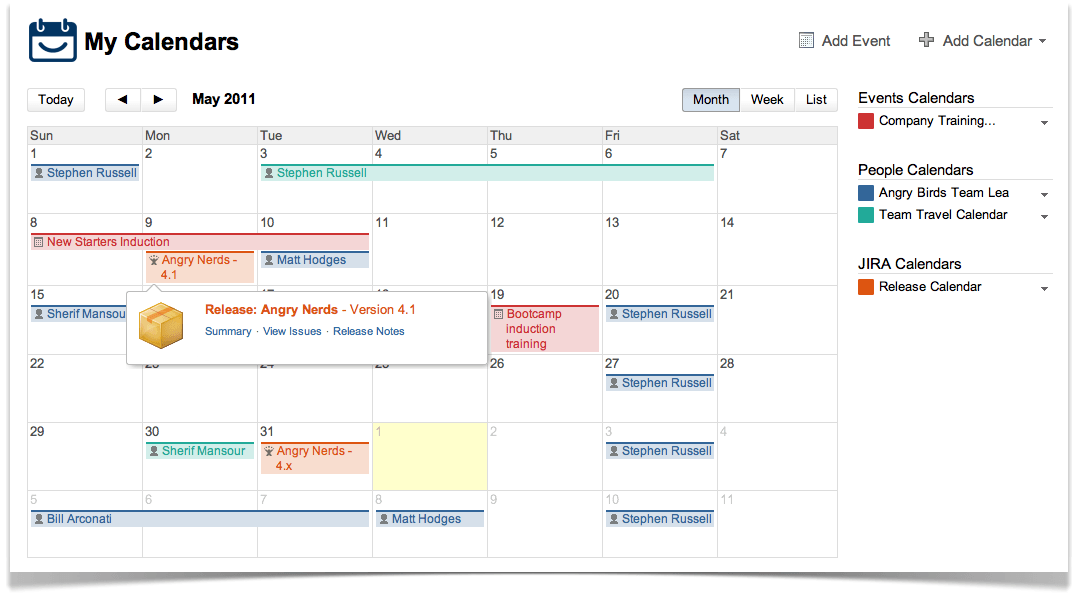

The next stage of Atlassian’s mission to make Confluence more appealing to non-technical users was the launch of Team Calendars in June 2011.

Team Calendars was a major step toward Atlassian’s goal of not only broadening Confluence’s appeal but also making the product more collaborative. Team Calendars allowed users to create and share calendars with their team or an entire company. They also supported file attachments at launch, which allowed users to connect events to internal documentation such as travel itineraries or contingency plans for team vacation coverage. Calendars could also be connected to Jira, which made it practically effortless for product and marketing personnel to see key events such as product release timelines created by engineering teams, or coordinate customer support responses based on employee availability.

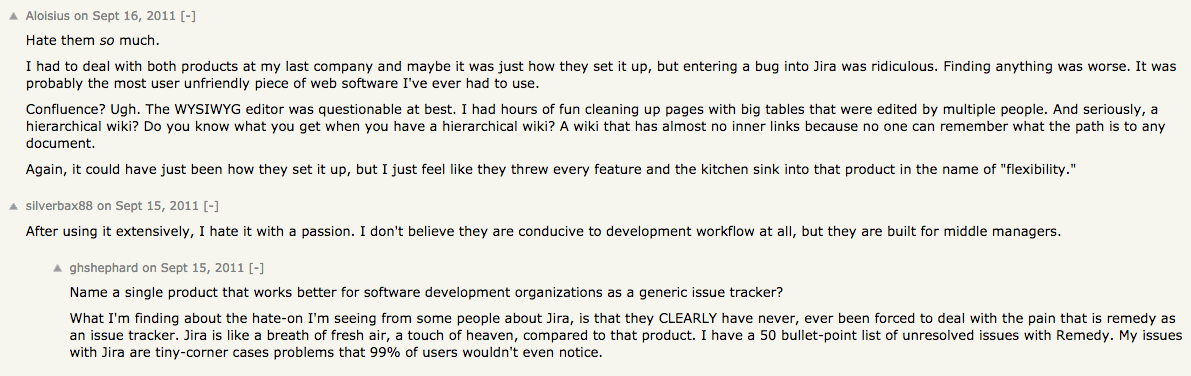

By 2011, both Jira and Confluence were commonplace across the enterprise and at more than a few startups. Depending on who you asked, Atlassian’s tools were either elegant, sophisticated solutions to difficult legacy problems or unwieldy, bug-ridden messes that looked bad and felt worse. Ironically, Jira and Confluence’s most vocal detractors were often the very same engineers Atlassian had built its tools for in the first place.

Atlassian had been intently focused on broadening Jira and Confluence’s appeal beyond programmers––but had done very little to ensure that its core technical audience continued to enjoy using the product.

The launch of Team Calendars made Confluence significantly more useful to a much broader audience. However, as it had in 2010 prior to the launch of Table Filters and Charts, Atlassian took its foot off the gas for more than a year after the release of Team Calendars. The next major update to the product came 13 months later in July 2012 with the release of Draw.io for Confluence.

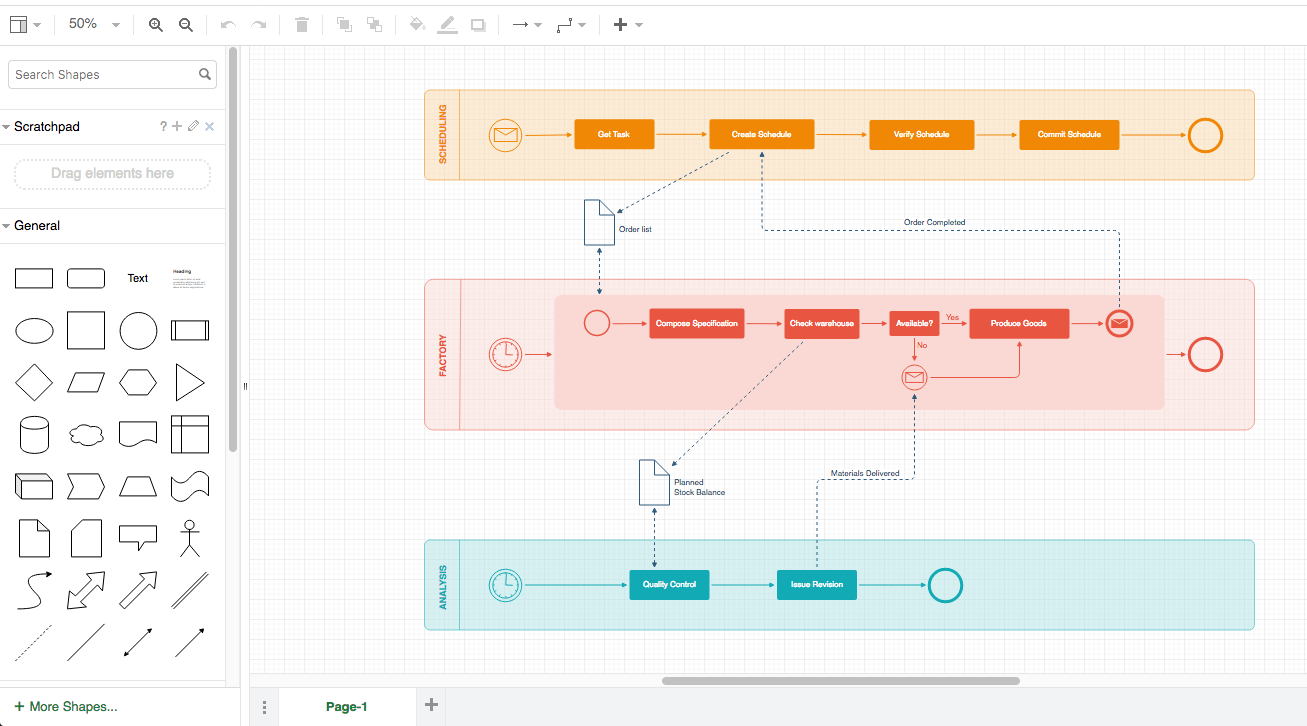

Confluence users had been able to create diagrams and flowcharts for some time thanks to Confluence’s Gliffy integration. Draw.io took that functionality to a whole new level.

Draw.io had significantly more features and functionality than Gliffy, including the ability to export diagrams as .vsdx files, support for touch-based devices, and a customizable interface. The tool quickly became one of the most popular apps in the Atlassian Marketplace, and Draw.io has since become the highest-rated Confluence app, a distinction that Draw.io has held for the past six years.

Confluence had become easier and easier to use as well as significantly more useful to a variety of roles across the enterprise. However, it wasn’t truly indispensable yet. Atlassian wanted to make Confluence central to productivity, not just a subset of specific tasks. To remedy this, Atlassian unveiled its latest major update in September 2012––the WorkBox.

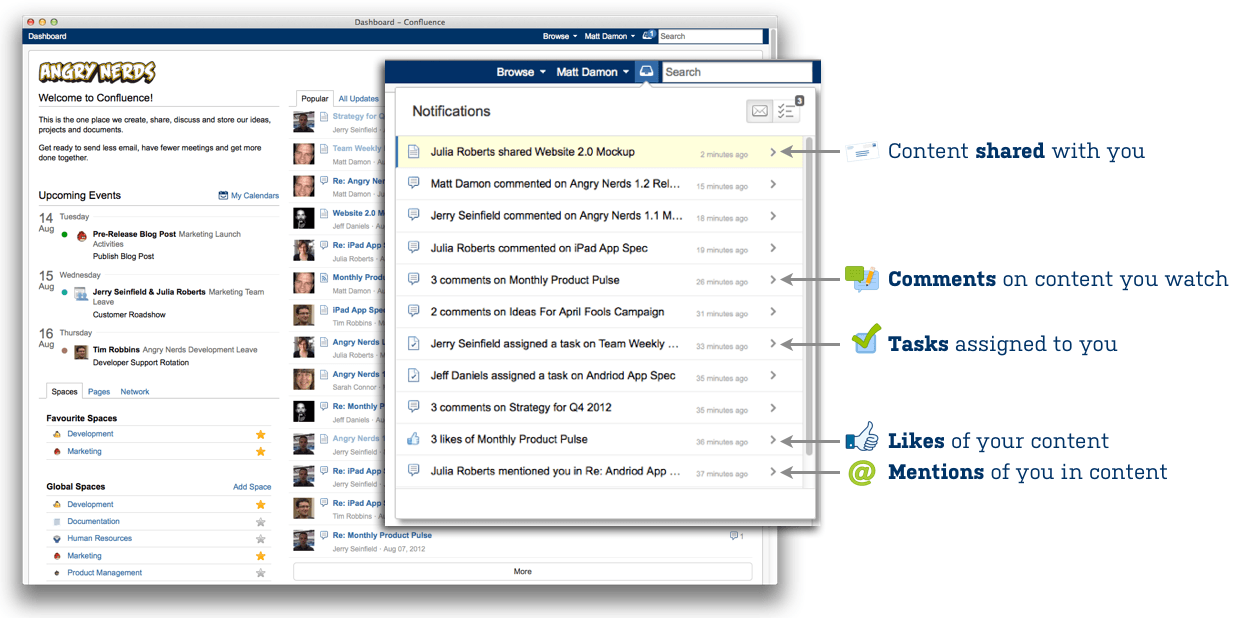

WorkBox was Confluence’s task management system. Essentially an activity stream embedded within Confluence, WorkBox allowed users to get more done without leaving the application. Users could track to-do items assigned to them by others, assign tasks to colleagues using @mentions, and add action-item checklists to project pages.

WorkBox wasn’t particularly revolutionary in and of itself. Dozens of companies were building similar activity stream alternatives to email. The one drawback of WorkBox was that it added very little in terms of either new functionality or improved workflow. By 2012, even Microsoft Outlook had become significantly more robust and offered much of the same functionality as WorkBox.

After the launch of WorkBox, Atlassian went dark for another six months until it released Confluence Blueprints in March 2013.

Blueprints were an extension of the Atlassian Marketplace. Prior to the launch of Blueprints, Confluence users had to configure their own add-ons and extensions manually. Now, users could choose from a selection of pre-built templates designed to help non-technical users get up to speed with Confluence faster.

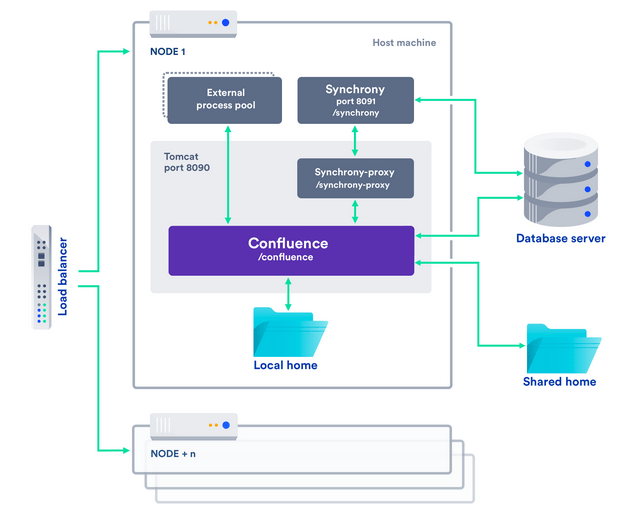

By early 2014, more than 8.5 million employees at 25,000 companies were using Jira and Confluence. The products’ growth had been steady, and Atlassian’s attempts to make Confluence more accessible and useful to non-technical personnel were paying off. In July 2014, Atlassian took another step toward its mission to dominate the enterprise when the company unveiled Jira Data Center.

Data Center was a product tier designed specifically to meet the needs of enterprise companies. Subscribers to Data Center received high-level customer support and technical account management services. The service also allowed companies to run Jira installations across multiple nodes. Although Data Center was primarily focused on Jira, Confluence was added to the Data Center product offerings later that summer. Data Center was initially priced at $24,000 annually, which covered a license for a single software product and support for up to 1,000 users. Atlassian also offered Data Center as a premium service for $35,000 annually, with the company’s technical account management service priced at $60,000 per year.

Confluence had grown quickly thanks to its popularity among engineers. As smart as Atlassian’s launch strategy had been, the company’s plans for Confluence were much more ambitious. Atlassian wanted to conquer the enterprise as a whole, not just wikis for engineers. However, while Confluence had taken several important steps toward becoming a more collaborative product and amassed a growing userbase of enterprise clients, it still had a long way to go before realizing its ambitions.

2015-Present: Knowledge Sharing > Knowledge Management

Atlassian was in a very strong position going into 2015. Both Jira and Confluence continued to grow, and Confluence in particular had experienced strong growth thanks to Atlassian’s focused push into the enterprise. Atlassian’s revenue had increased from $67.9 million in Q3 2014 to almost $102 million in Q3 of 2015. The company was already profitable––albeit modestly, with net profits of just over $5 million in Q3 2015––and had taken comparatively little venture funding in order to become so. Investor expectations were high––and Atlassian wasted little time exceeding them.

Atlassian filed for its IPO in December 2015. The company priced its IPO at $21 per share and ended its first day of trading up 32%, giving Atlassian a valuation of almost $6 billion.

Later that month, the Atlassian Marketplace achieved a milestone of $120 million in direct sales revenue. Marketplace had been incredibly popular with engineers and non-technical users alike.

By the end of 2015, there were more than 2,000 applications available through the Marketplace. The popularity of apps such as Draw.io had generated significant income for several developers, and more than 15 developers had earned over $1 million in direct sales by the end of 2015. Marketplace was a solid revenue stream for Atlassian, too, as the company took a 25% cut of all sales made through the platform.

Atlassian kicked off 2016 by hiring Sri Viswanath as the company’s CTO in January. Prior to joining Atlassian, Viswanath spent almost a decade in the engineering trenches at Sun Microsystems before becoming CTO at Groupon.

By the time Atlassian hired Viswanath, the company was in urgent need of a technical overhaul. The company had amassed a considerable amount of technical debt over the course of 15 years, and both Jira and Confluence’s codebases badly needed updating. Companies with more than 2,000 employees often experienced great difficulty using Atlassian’s products, as their architecture simply wasn’t built to handle so many concurrent users. That’s when Viswanath decided that Atlassian would refactor almost all of its code and migrate from its own proprietary data centers to Amazon Web Services.

This was no small undertaking. By the time the decision to migrate to AWS was made, Atlassian had tens of thousands of enterprise clients, some of whom had many thousands of users.

“We spent a lot of time figuring out how to automate everything we did, including figuring out which customers should be migrated every night, the process of migration itself. Post-migration, all the tests we needed to run––not just immediately after, but how do you make sure that beyond that… customer satisfaction is at the same level before and after.” — Sri Viswanath, CTO of Atlassian

Codenamed Vertigo, the migration project took almost two full years to complete. Fortunately, the company was already using AWS for select microservices prior to the migration, such as a media service that allowed users to preview file attachments. Viswanath and his team automated as much of the process as they could. Incredibly, Atlassian was able to successfully migrate all its customers from its own data centers to AWS with virtually no major disruptions in service.

The move to AWS wasn’t just necessary because Atlassian’s codebase was outdated. It allowed the company to iterate much more quickly than it ever had in the past. Product development cycles in the enterprise are typically longer than others, but Atlassian had developed a reputation for being relatively sluggish when it came to responding to customer requests or bug fixes. Migrating to AWS allowed Atlassian to be much more agile in terms of product development.

Having migrated thousands of enterprise customers to the cloud over a two-year period, Atlassian was in no hurry to ramp up product development cycles or start working on new products.

Aside from Jira and Confluence, Atlassian’s bread and butter, the company had a diverse portfolio of products that had grown steadily over the years to include Bamboo, Bitbucket, Crucible, HipChat, and FishEye. These products didn’t generate nearly as much revenue as Jira and Confluence, but they did represent an opportunity to capitalize on a largely neglected revenue stream that the company hadn’t prioritized. To remedy this, Atlassian announced its Stack subscription product in June 2017.

Atlassian Stack was priced at $186,875 per year, which included almost every Atlassian product and licenses for up to 1,000 individual users. Although this might have seemed steep even for an enterprise product bundle, it actually represented great value for subscribers.

The Atlassian Stack included:

- Data Center versions of Bitbucket, Confluence, Jira, and Jira Service Desk

- Server versions of Bamboo, Crowd, Crucible, FishEye, HipChat, and Jira Core

- The Portfolio and Capture add-ons for Jira, and the Questions and Team Calendar add-ons for Confluence

Alongside the Atlassian Stack, the company also introduced its DevOps Marketplace in June 2017, which featured more than 200 specialized add-ons and integrations at launch.

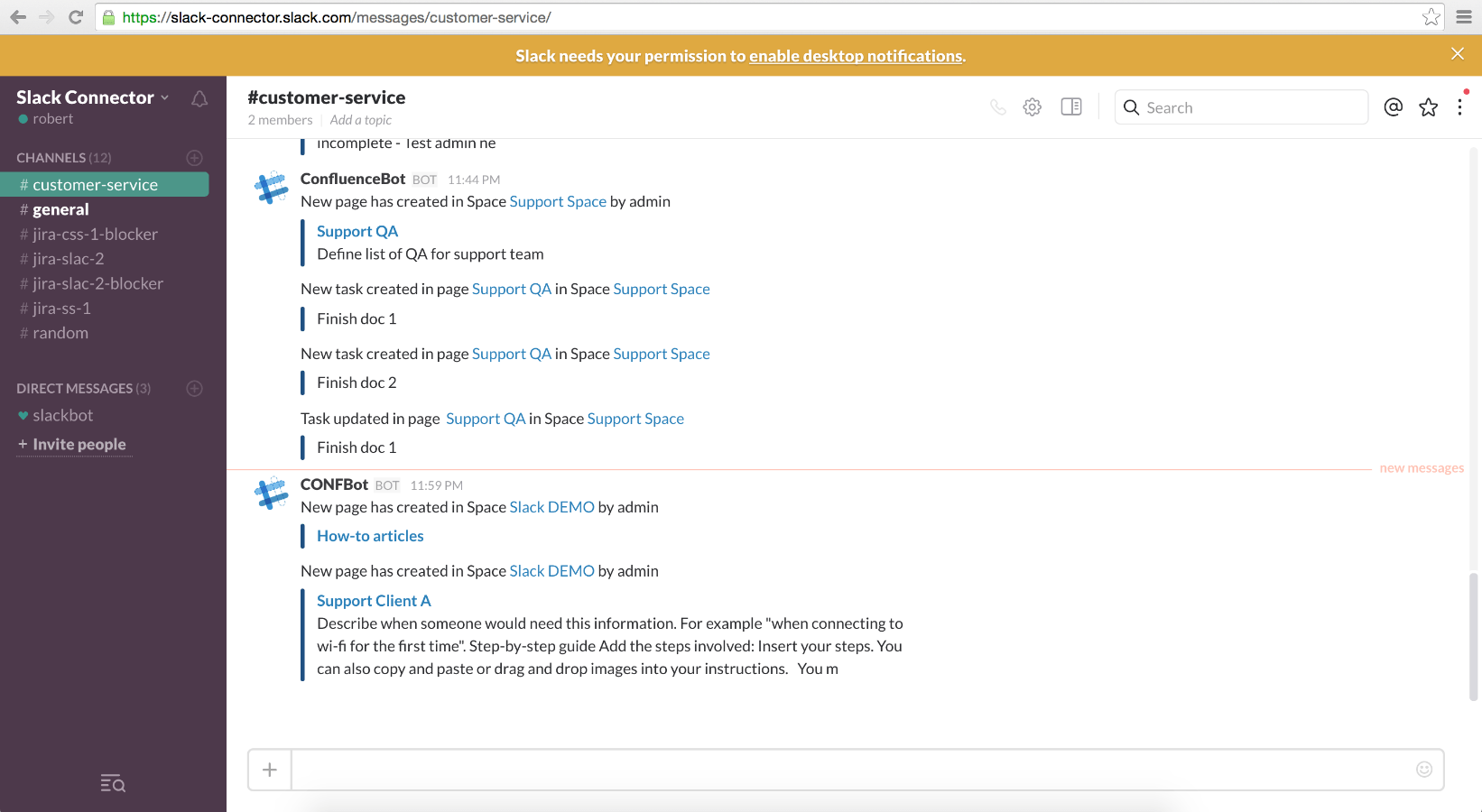

After the launch of Atlassian Stack and the DevOps Marketplace, Atlassian went dark for another 14 months. During this time, neither Jira nor Confluence underwent any significant updates. Aside from the appointment of Pratima Arora as the company’s new Head of Confluence in September 2017, there was very little public activity at Atlassian during this time. The next significant update to Confluence wouldn’t come until one year later in September 2018 when Atlassian unveiled its Slack cloud app for Confluence.

Confluence for Slack was both predictable and necessary. Atlassian had offered Slack integrations with Bitbucket, Jira, and Trello for some time, and it was inevitable that Confluence would receive the same treatment. The integration allowed users to respond to Confluence messages directly within Slack, preview Confluence documents inline, and customize Slack notifications to alert users to changes made to content in Confluence.

The following month in October 2018, Atlassian overhauled both Jira and Confluence and updated their pricing to match. Atlassian increased the price of many of its cloud products, including Confluence. As is typical with many enterprise products, the price increase was dependent on which products a company was using and how many users that company was licensed to support.

However, while the new pricing was unlikely to deter many potential customers, Atlassian sweetened the deal by announcing a sweeping overhaul of its two core products. One of the biggest additions to Jira was Roadmaps, a visualization tool that allowed users to create pitch decks from project timelines. Thanks to Confluence’s new home on AWS, Atlassian also increased the maximum number of users within a single organization to 5,000.

“When I think about workplace trends, I think about how you can make employees and teams do their best work by making information readily accessible and break those walls. We need to make information flatter and let everybody work together to come up with the best outcomes. Work is becoming more about learning, which is fascinating.” — Pratima Arora, Head of Confluence of Atlassian

Atlassian has built a truly formidable product with Confluence. But as competition intensifies from new products like Notion and Coda, it’s becoming more and more important for Confluence to focus on the customer to make sure that it doesn’t lose any market share.

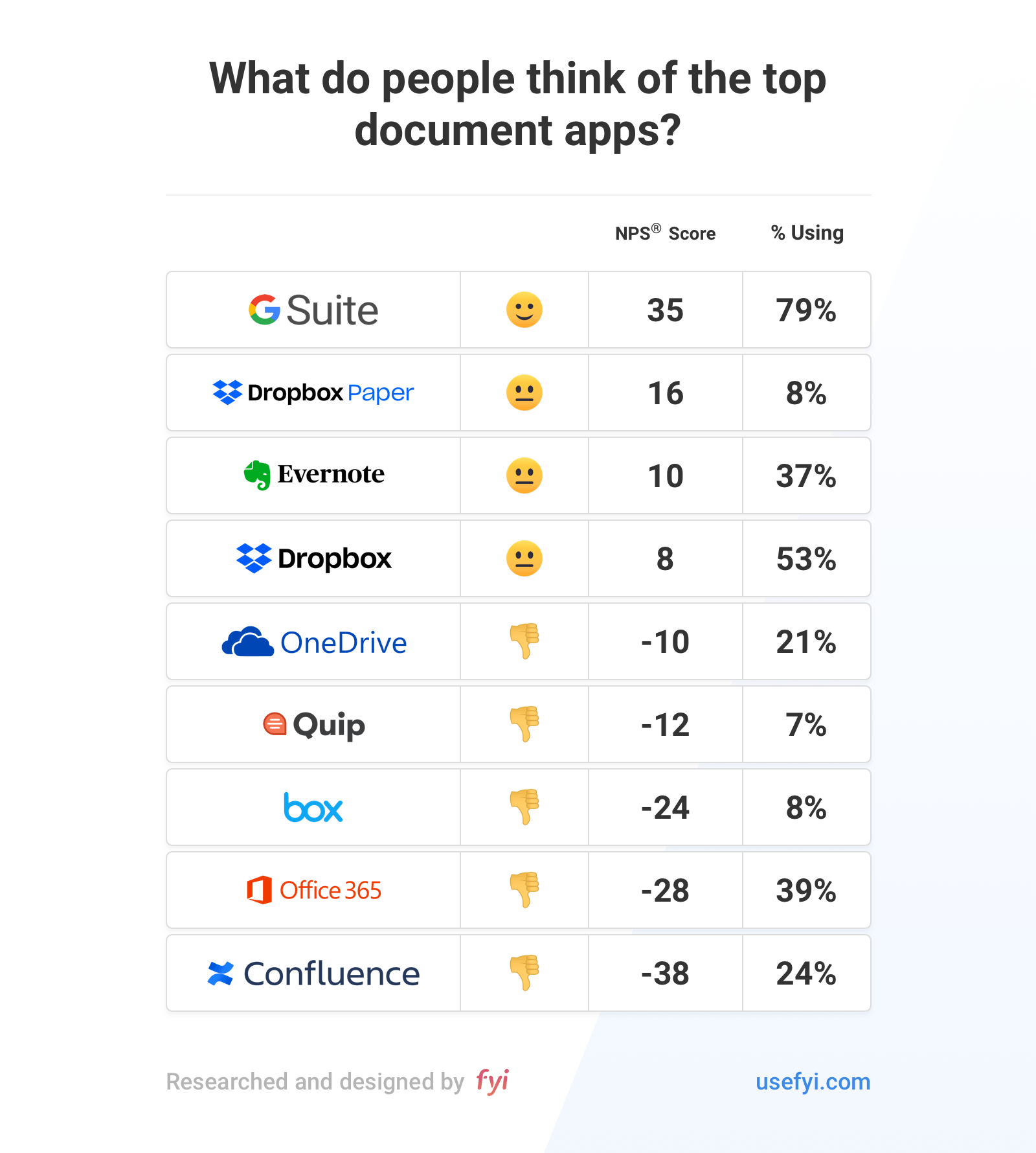

Based on our research, customers aren’t very satisfied with Confluence. We’ve conducted two surveys to find out Confluence’s Net Promoter Score (NPS). In 2017, we surveyed 650 people about popular document apps. Confluence’s NPS at the time of that survey was -25. Ouch. We did another survey in 2018 of 249 people. In that survey, Confluence received an even lower score of -38.

A Net Promoter Score between 0 and -100 indicates that customers are having bad experiences with the product. People are having such negative experiences, that they are likely actively telling other people to avoid the product.

We’ve also compared Confluence to other document apps on review site G2. Confluence has the lowest score on G2 when compared to Google Docs, Dropbox Paper, Microsoft Word, Coda, and Notion.

Confluence’s customer satisfaction scores are consistent with the general tenor about Confluence and Jira. People’s feelings about Confluence and Jira have even evolved into a bit of a joke in the tech community.

Things I hate the most:

1. Milk

2. Broccoli

3. Jira

4. Confluence— George Bougakov Ⓖ (@gbougakov) June 13, 2019

Marie Kondo: What is this?

Me: Its called Jira

Marie: Does it Spark Joy

Me: Absolutely not

Marie: Thank it, and then discard it— I Am Devloper (@iamdevloper) January 30, 2019

And even those who love Confluence are aware of the overall negative sentiment.

I actually like @Confluence I've never understood why there's so much hate

— Sara Jacobson (@sarajacobson495) May 8, 2019

In spite of this sentiment, Confluence has been and continues to be massively successful. The product has changed dramatically since it was launched 15 years ago. Confluence has evolved from a simple wiki tool built for engineers to a comprehensive knowledge management system aimed at both technical and non-technical personnel.

With Confluence, Atlassian has demonstrated that it is more than capable of developing popular products that can handle the demands of the enterprise. The only question now is how far Atlassian can go.

Where Could Confluence Go from Here?

Over the years, Confluence has gradually evolved from a wiki tool aimed solely at software developers to a diverse knowledge management tool with an array of applications. Where could Confluence go from here?

- Addressing legacy issues with the product. Despite Confluence’s popularity and ubiquity in the enterprise, Atlassian has a reputation for failing to respond to customer feedback. With an NPS score of -38, Confluence is among the lowest-scored software products on the market, in any category. If Atlassian hopes to maintain Confluence’s momentum and growth trajectory, it must address the legacy issues that have irritated long-time users for years.

- Improving collaboration within Confluence. Atlassian has dragged its heels in making Confluence a truly collaborative product. Confluence still lacks a real-time chat function, for example. As the workplace becomes increasingly collaborative, Atlassian will likely have to address this shortcoming if it wants to head off potential competitors seeking to encroach on Atlassian’s market share.

- Faster iteration and greater focus on the customer. The company hasn’t been as focused on the customer. As competition in the collaboration and productivity market intensifies, Atlassian may be forced to spend more time focusing on the customer. This may also include faster iteration of the product itself, instead of buying growth through acquisitions like they have done in the past.

What Lessons Can We Learn from Confluence?

Atlassian took a novel approach to the development of Confluence by leveraging the success of a complementary product to launch a second, and by targeting a highly specific type of user before expanding to other use cases. What can we learn from Confluence?

1. Give customers what they want. Jira is far from perfect, but it’s arguably one of the best issue-tracking systems out there. Atlassian almost had to develop Confluence to complement its flagship product, Jira.

As the de facto documentation personnel on most product teams, software developers urgently needed a documentation tool that could help them do their jobs more efficiently. Although this put Atlassian under a considerable amount of pressure, building a second product on top of the success of the first was also a huge advantage for the company.

Take a look at your ideal customer or buyer persona:

- Could you feasibly do what Atlassian did and target a highly specific demographic or user persona, then expand to a broader market down the road? How might you go about this?

- Are there any opportunities to leverage your current or existing product to solve a related problem experienced by your users?

- Talk to your customer success reps or take a look at your customer feedback. What’s the one thing your users are always asking for that you haven’t given them––and why haven’t you given it to them yet?

2. Really know your customer. One of the smartest things Atlassian ever did was to target a specific type of user that the company knew intimately. This knowledge allowed Atlassian to not only give that initial userbase exactly what they wanted and needed but also made it significantly easier for Atlassian to rely on word-of-mouth to raise awareness of the product rather than costly advertising campaigns.

Think about your product and your current customers:

- Did you decide to solve a specific problem or appeal to a specific type of user? What was the reason behind that decision?

- How are you leveraging your institutional knowledge about your users to improve your product?

- How would you go about translating the popularity of your product among a specific type of user into a broader upmarket appeal? To take this idea one step further, could you do so with a minimal (or nonexistent) advertising or marketing budget?

3. Be ready to make difficult decisions. Atlassian accrued a great deal of technical debt over the years. When the company finally acknowledged the need to migrate from proprietary data centers to AWS, this was no idle decision. Although the migration went off without a hitch, it could have been disastrous if it had been handled incorrectly.

Think about a time when you were faced with a difficult decision:

- If you had made the wrong call, could your company or product have realistically recovered?

- How much of that predicament was on you and how much could be blamed on external factors beyond your control?

- What was the single biggest takeaway from that experience, and how could you avoid similar difficulties in the future?

Land and Expand

Atlassian has never been a “typical” enterprise company. Despite its reputation for slow development cycles and legacy product issues, Atlassian successfully grew Confluence from a highly specific tool designed for engineers to a robust documentation tool with broad appeal across entire organizations––and created a profitable, growing company in the process.

However, if Atlassian wants to maintain the momentum it has built during the past 17 years, it must respond to wider changes in how and where people work by becoming a genuinely collaborative product. If Atlassian can pull that off, there’s no telling where the company could go in the future.