How Zoom Became the Best Web-Conferencing Product in the World in Less Than 10 Years

In 2011, Cisco’s then-VP of engineering, Eric Yuan, tried to persuade his fellow executives that they urgently needed to improve WebEx, Cisco’s web-conferencing product.

At that time, Cisco’s strategy for web conferencing didn’t involve improving existing products. Despite the fact that WebEx had been a costly acquisition, and the product was an important part of Cisco’s business.

Cisco didn’t listen.

Undeterred, Yuan did what any confident entrepreneur would do, he promptly resigned to start his own company. That company was Zoom.

In just four years, Zoom’s video-conferencing product went from scrappy upstart to being used by tens of millions of people around the world. Not only that, but the company also achieved profitability very quickly, thanks to Yuan’s lean, focused approach to product development and his customer centricity.

Here are a few of the things we’ll be looking at in this article:

- How a long-distance relationship inspired Yuan to create a better web-conferencing product

- How Zoom was able to succeed despite its late entry into an already crowded market

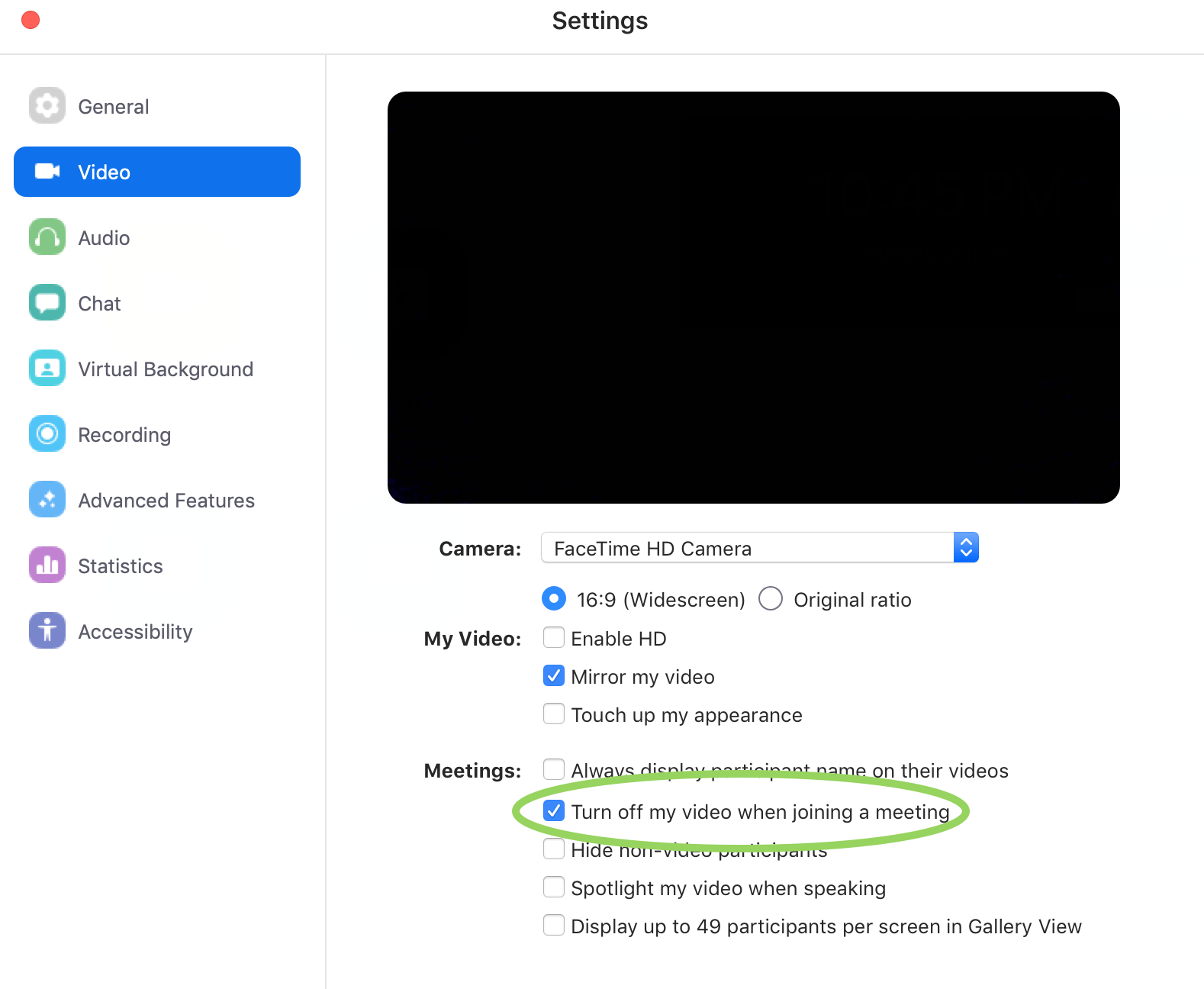

- How even well-intentioned design decisions can have unintended consequences

Yuan was convinced there had to be a better way for people to collaborate via online video. However, before Yuan could realize his vision, he needed funding––and he got it from a former colleague at Cisco, who believed in that vision.

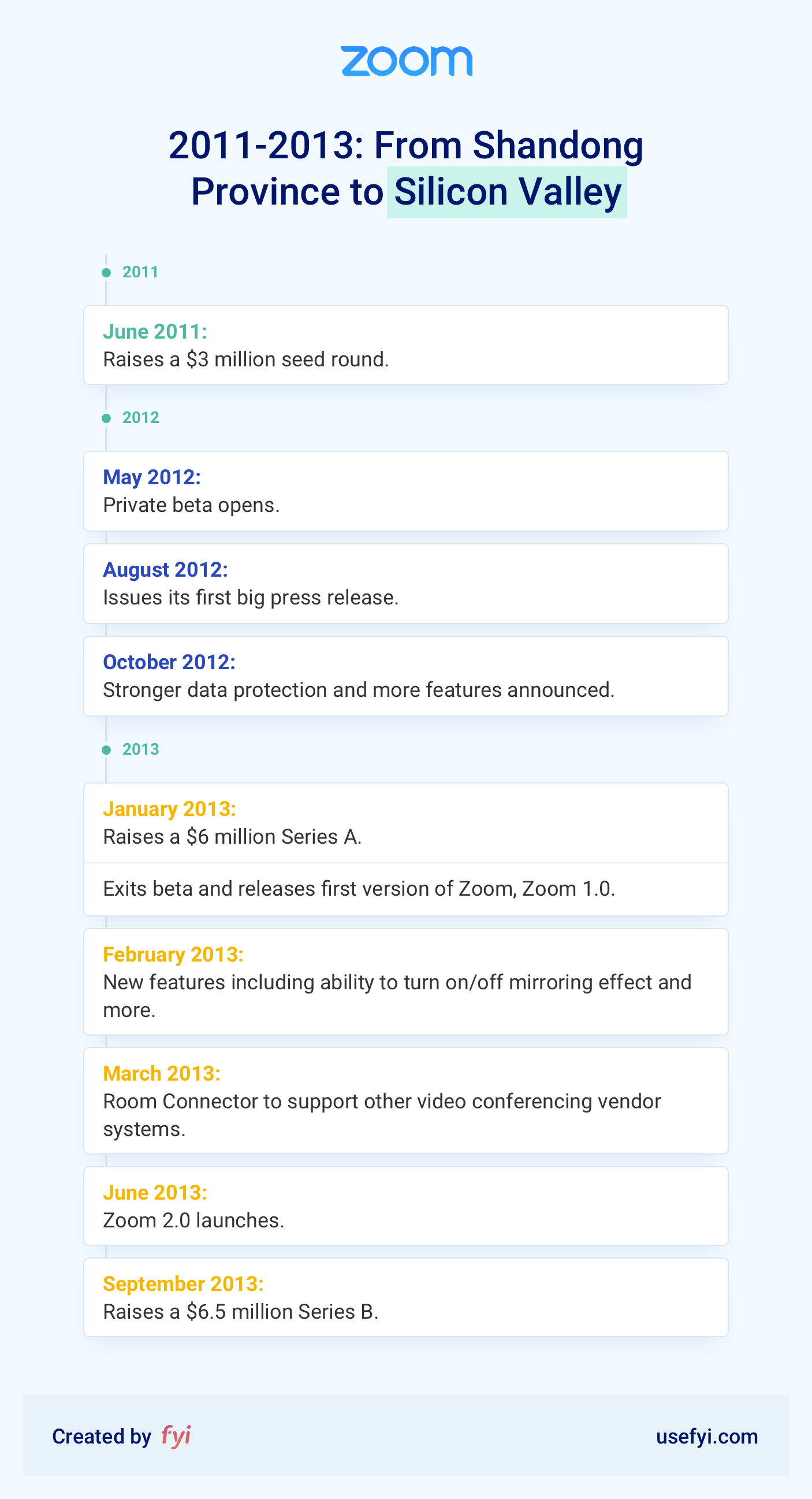

2011-2013: From Shandong Province to Silicon Valley

Eric Yuan had been thinking about video-conferencing technology for more than 20 years before he quit his job at Cisco to start his own company.

In the late ’80s, Yuan was a freshman studying applied mathematics and computer science at the Shandong University of Science and Technology, in China’s Shandong Province. Yuan’s girlfriend at that time was also studying in China, but at a college several hours and multiple train rides away.

Yuan and his girlfriend attempted to navigate the pitfalls of long-distance dating. All the while, Yuan dreamed of a handheld device that would enable two people to see and speak with each other from anywhere in the world.

“And quite often, I was thinking, in the future, if you can have something like a small device where you can the press one button, you can see someone, you can talk with someone. I think that’d be great. It’s more like a daydream, right? So I never thought about video conferencing, but later on when I saw the FaceTime when I built Zoom I feel like, ‘Wow. That’s just great.’ If we have this, many years ago, that’d be awesome.” — Eric Yuan Founder of Zoom

Fast-forward 10 years or so to 1997. From China, Yuan had seen the rise of American Internet companies, such as Netscape and Yahoo. Believing that China was still at least a decade away from fostering a tech ecosystem like that in the United States, Yuan sought a visa to travel to the United States and pursue a career in technology.

Consulate officials denied Yuan’s application for a visa eight times.

Yuan’s luck would change on his ninth and final visit to the U.S. consulate, when he was granted a visa to travel to the United States. Shortly after landing in America, Yuan moved to Silicon Valley. He was in awe of the number of companies working on exciting new technologies compared with his native China. Soon after, Yuan accepted an engineering role at WebEx Communications in Milpitas California, in Silicon Valley’s South Bay.

Yuan was one of a team of engineers responsible for building the initial version of WebEx’s web-conferencing product.

WebEx was built using a proprietary technology stack that the company called MediaTone. The product was available for a wide variety of platforms, including Windows 95/98/ME, Mac OS 9 and OS X, Linux, and Palm OS, among others. Yuan himself had been responsible for many of WebEx’s innovations. Yuan was named as the inventor of more than 30 issued or pending patents during his time at WebEx.

Cisco acquired WebEx Communications for $3.2 billion in 2007, almost $4 billion in 2019 dollars. At the time of WebEx’s acquisition, the product had around 2 million customers. Alongside WebEx’s proprietary technologies, Cisco inherited many members of the WebEx team upon acquiring the company––including Eric Yuan.

WebEx grew rapidly under the Cisco umbrella. Yuan’s hard work earned him numerous promotions before landing him the role of Corporate Vice President of Engineering.

During this period, Yuan oversaw immense growth of the WebEx product. He grew the product’s engineering team from a handful of developers to a team of more than 800 engineers. Annual revenue expanded to upwards of $800 million.

WebEx may have been innovative in its early days. But after a decade, the product felt stagnant, and customers were frustrated. The product’s multistep installation process was cumbersome. Connections were often unstable. Audio and video quality were inconsistent. WebEx made it relatively easy for meeting attendees to share files with one another. But scheduling calls and conducting virtual meetings were frustrating.

As Yuan neared the end of his tenure at Cisco, he met with many WebEx customers to discuss the product.

The only constant from one customer to another was disappointment.

“Before I left Cisco, I spent a lot of time talking with WebEx customers. And every time, when I talked with a WebEx customer, after the meeting was over, I felt very, very embarrassed because I did not see a single happy customer. And I tried to understand, why is that? And I summarized all the problems all those WebEx customers they shared with me. You know, finally, I realized all those problems are brand new problems.” — Eric Yuan Founder of Zoom

People weren’t using WebEx because they wanted to; they were using WebEx because they had to. WebEx had been developed to solve problems that were not as urgent as they once were.

WebEx had initially aimed to make sharing files with conference-call attendees easier. The bigger problem was that WebEx hadn’t kept pace with broader changes in how people worked. Much of WebEx’s codebase hadn’t been updated in years. Due to limitations in WebEx’s functionality, many WebEx users also had to rely on multiple conferencing tools to get their work done.

To Yuan, the choice was clear: Cisco could either commit to updating WebEx, or it could build an entirely new product from scratch.

The problem was that Cisco didn’t want to invest in modernizing WebEx or building a new conferencing product. Yuan tried repeatedly to convince his colleagues that investing in WebEx wasn’t just important—it was critical to the product’s continued success and the success of Cisco’s broader web-conferencing business.

Yet Yuan’s pleas fell on deaf ears.

Despite Cisco’s reluctance to listen, Yuan’s confidence in his idea was unshakable. That confidence helped Yuan convince about 40 engineers on his former team to quit Cisco and join him in building a new web-conferencing product. Yuan said later it was much harder to convince his wife that his instincts were right.

Yuan wasn’t the only senior exec at Cisco to leave the company in April 2011. Dan Scheinman, Cisco’s head of corporate development, also left that month. Yuan reached out to Scheinman to ask if he could show Dan what he’d been working on. However, while Scheinman believed in Yuan’s abilities as an engineer, he was much less certain about the prospects of Yuan’s fledgling business.

Despite Scheinman’s reservations about Yuan’s likelihood of success, he wrote Yuan a check for $250,000 in April 2011. He did so largely on the strength of his convictions about Yuan himself. At that point, Yuan’s startup was called Saasbee. With Scheinman’s input, Yuan narrowed his company’s potential name down to four contenders: Hangtime, Poppy, Zippo, and Zoom. Around that time, WebEx’s CEO, Subrah Iyar, invested $250,000 of seed funding into Yuan’s company, mostly due to Iyar’s belief in Yuan’s vision and talent.

Yuan used the majority of the initial investment funding to hire engineering talent in his native China. This was largely a cost-saving measure; Chinese engineers were cheaper than their American counterparts. More engineers meant a tighter product.

For the next year, Yuan’s team worked hard on the first iteration of what would become Zoom. Yuan himself worked out of the company’s tiny office in Santa Clara. The very first version of Zoom was released on August 22, 2012.

“Today, group video meetings are the realm of businesses, but they can be hard to facilitate. Users have separate accounts for each video-calling application, which requires them to remember different usernames and passwords, and the video quality is often poor. Zoom.us takes the complexity out of connecting to friends and colleagues by offering a single-click solution that works whether you are on an iPad using WiFi, an iPhone using Edge, or a PC connected to Ethernet and lets everyone participate in the conversation seamlessly.” — Eric Yuan Founder of Zoom

The early Zoom product was impressive. Initially available as a web app and for iOS, Zoom allowed up to 15 concurrent meeting attendees. It was optimized to run well even on weak or unstable wireless connections. Zoom’s audio and video quality were both very high. The app worked seamlessly on mobile. It automatically detected users’ operating systems and screen resolutions. Attendees didn’t have to download anything or even log in; only meeting hosts had to have a Zoom account.

What set Zoom apart from the competition wasn’t just the clarity of the video—it was how well Zoom worked on mobile.

At that time, many web-conferencing companies, such as Vidyo, were focused on hardware solutions for desktop conferencing. Better hardware meant better image and audio clarity. This was seen as especially important for dedicated, specialized applications of video conferencing, such as telemedicine. The telemedicine market in the United States alone grew by 60% between 2012 and 2013. The education sector was also driving demand for high-quality video-conferencing solutions as synchronous learning models became increasingly popular. But mobile remained a critical vulnerability for many web-conferencing companies––a weakness Zoom quickly capitalized upon.

In January 2013, Zoom 1.0 was released to the world. The company timed the announcement to coincide with its $6M Series A round, which was led by Qualcomm Ventures. Zoom supported up to 40 concurrent attendees from launch––more than any other web-conferencing product at that time. Zoom ran seamlessly on all platforms, including iOS and Android devices. The product’s screen-sharing functionality was smooth, and the image quality was superb. The only restriction on the freemium product was that calls were capped at 20 minutes for meetings with more than two attendees.

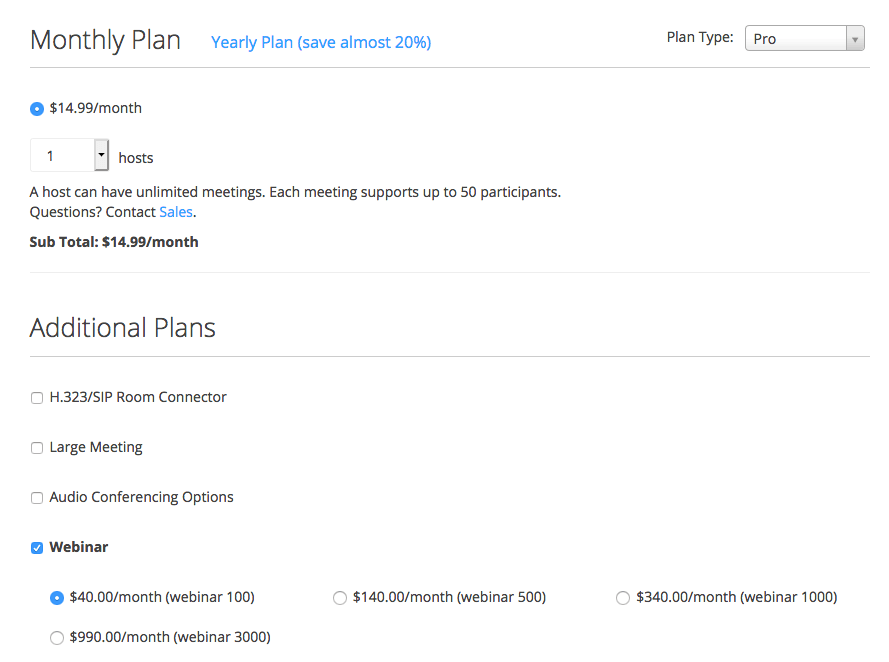

The product was initially available in three tiers: Freemium, Business, and Enterprise. The Business and Enterprise tiers were priced at $9.99 per host per month and had no restrictions on meeting durations.

In addition to the SMB market, Zoom smartly recognized the education sector as the significant opportunity it was. Zoom changed its pricing tiers shortly before launch to offer educational licenses of the product for just $0.99 per month. This gave Zoom a crucial opportunity to prove itself in a large potential market and establish a strong early-growth vector. Yuan confirmed later that Zoom planned to use much of its Series B round to expand overseas and strengthen its presence in the growing education and health care sectors.

Given Zoom’s strong initial growth, it’s easy to forget that the company did not yet have a dedicated marketing team. Initially, the product’s growth was almost entirely organic, driven mostly by word of mouth. This is another great example of how Yuan grew his company economically. Keeping customer acquisition costs as low as possible put Zoom on the path to profitability early on.

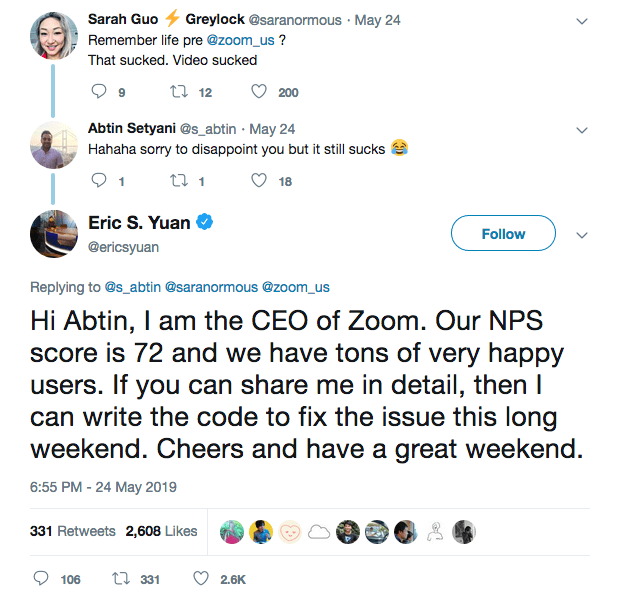

Even as his company grew, Yuan didn’t shy away from rolling up his sleeves and helping customers. Yuan often emailed customers who were considering leaving the product to learn why. Some of those customers became Zoom’s most loyal evangelists.

More importantly, this hands-on approach to customer support taught Yuan a lot about the problems customers were experiencing on a day-to-day basis. Even now, Yuan still takes the time to personally respond to user feedback because he genuinely cares about his users.

Zoom experienced strong growth throughout 2013. By June, more than 1.2 million participants had joined over 400,000 meetings in 2,500 cities across the globe. The company had entered into agreements with a range of higher-education institutions, including Kansas State University, the University of Northern Iowa, and Ottawa University.

By August 2013, Zoom was hosting more than 5,500 meetings every day.

In September 2013, Zoom raised $6.5 million as part of its Series B round led by Horizons Ventures. By this point, more than 4,500 companies and 3 million participants were using Zoom. An increase of 650% in individual users and a 350% increase in business users in less than 12 months.

Yuan and his company had seemingly accomplished the impossible. Zoom had fundamentally improved the web-conferencing experience in a crowded market with supposedly little room for newcomers.

Not only that, but Zoom had also managed to upstage several of the industry’s largest incumbents, including WebEx. Zoom was an incredibly strong product that was well positioned to continue its upward trajectory into upstream markets and the Enterprise. To do so, Zoom needed capital… and lots of it.

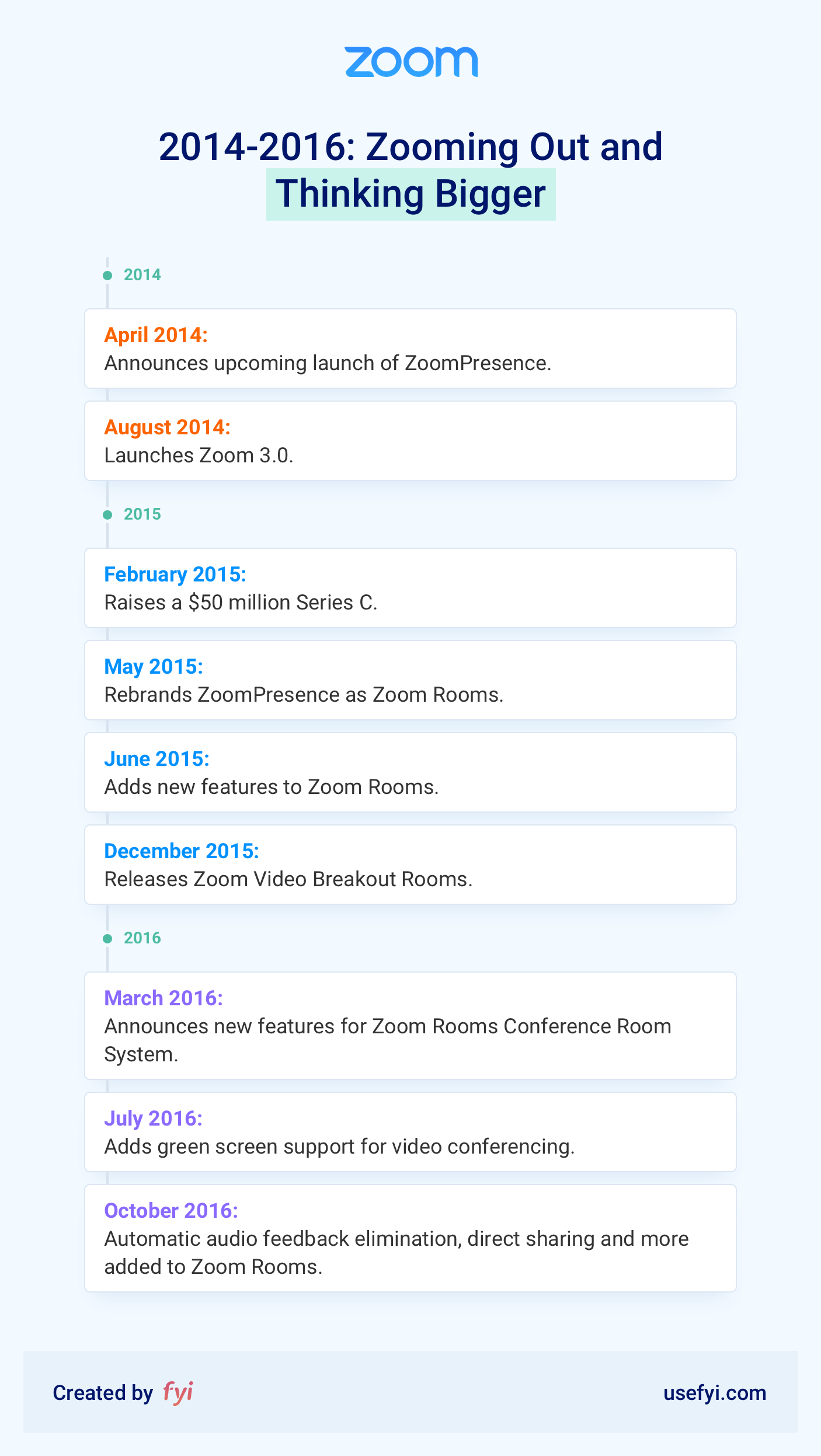

2014-2016: Zooming Out and Thinking Bigger

For the next two years, Zoom applied the lessons it learned during the product’s launch to scaling and expanding the business aggressively. Zoom might have lacked the resources of Cisco or Microsoft, but Zoom had one key advantage over legacy incumbents: agility.

Throughout 2014, many of the industry’s most powerful incumbents soon found themselves on the defensive. With video-conferencing hardware sales on the decline and few original ideas of their own, companies like Cisco had little choice but to imitate Zoom’s features in their own products. But as time would soon tell, it was too little, too late.

Surprisingly, for a company growing as quickly as Zoom was, the company made very few major updates to the product in 2014. One of the few significant updates to the product that year came in August, with the release of Zoom Presence.

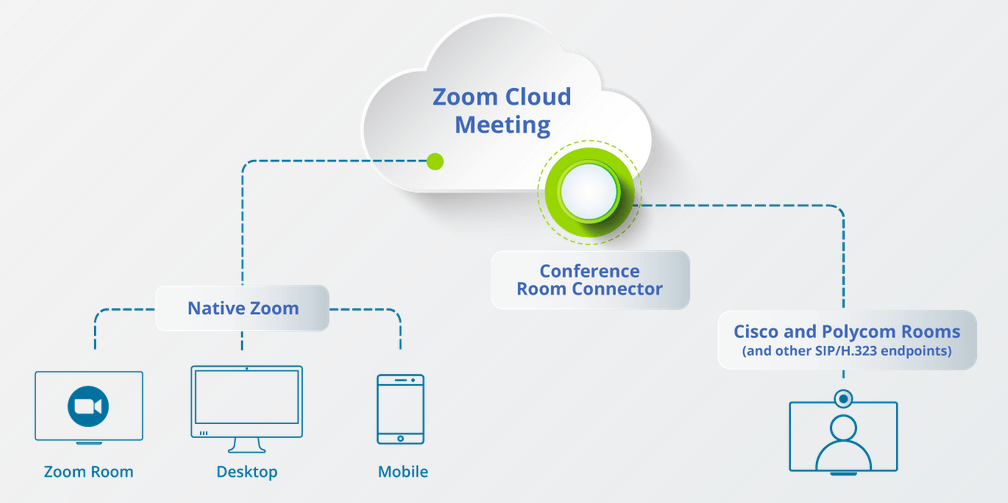

Presence was Zoom’s room-based video-conferencing product. Although room-based systems were falling out of fashion by 2014, they had not yet been replaced entirely. Room-based teleconferencing systems routinely cost tens of thousands of dollars. This meant that larger companies––the same companies Zoom was hoping to attract––were still likely to be looking for ways to derive value from these expensive investments.

However, backward compatibility and interoperability were significant issues. Many proprietary room-based conferencing systems didn’t play nicely with newer video technologies. This put many companies in a difficult position. They had little choice but to upgrade their systems if they didn’t want to be left behind. Simultaneously, they didn’t want to write off tens of thousands of dollars by abandoning their room-based systems entirely. Presence was an attempt to solve both sides of the problem.

Zoom Presence relied on the product’s Conference Room Connector. This system allows users to seamlessly combine Zoom meetings with meeting rooms from other conferencing products. Presence gave users the ability to schedule, launch, or join meetings directly from any device. Presence supported up to three individual displays per meeting and allowed hosts to control meetings via a remote-control interface in the app.

Presence might not seem that exciting as far as updates go. But the real brilliance of Presence wasn’t the product itself; it was the timing.

By 2014, administrators and IT professionals had been wrestling with the implications of BYOD or bring your own device policies for several years. Tensions between the desire for flexible BYOD policies and the comparatively weak security features of many mobile devices had been particularly problematic for enterprise companies. But Presence was a plug-and-play system.

Individual departments or entire organizations could create custom room-based conferencing systems using Zoom as a platform. This meant companies could continue to use their expensive proprietary video hardware and attendees could use their own devices.

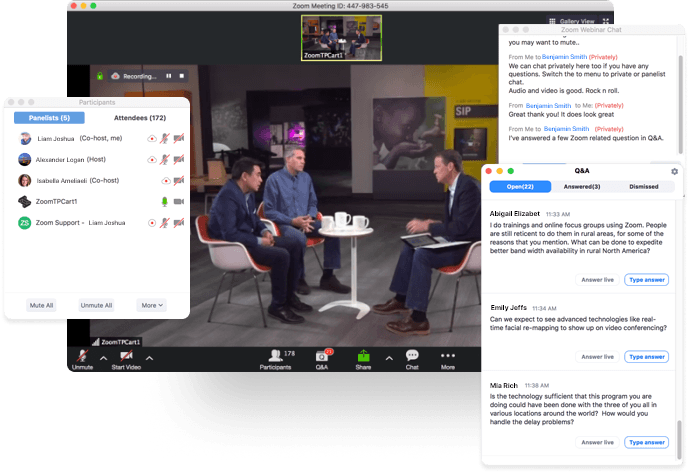

In August 2014, Zoom unveiled its Video Webinar platform. The service was initially positioned as an add-on to the core Zoom product and was structured into one of four tiers. Zoom’s platform supported up to 25 participants per webinar. Hosts could then choose to pay for between 100 and 3,000 attendees. This made Video Webinars highly scalable and allowed hosts to pay only for the audience size they required.

Zoom’s Video Webinars aimed to improve webinars in much the same way as the core Zoom product improved web conferencing. Despite the potential value of webinars, the actual webinar experience was poor across most products available at that time. Video and audio quality were poor. Hosts often experienced input delay when sharing their screens with attendees, particularly on high-latency connections. The maximum number of attendees was often quite low.

Zoom had already shown that there was ample room in the video-communications space to support another web-conferencing product. If Zoom could improve virtual meetings, why couldn’t it improve webinars, too?

Similar to the launch of the core Zoom product, the timing of the launch of Zoom Video Webinars was perfect. It was around 2014 when marketers––and content marketers in particular––began to figure out that webinars could be a powerfully effective lead-generation strategy. Alongside in-person events, case studies, and video content, webinars were seen as one of the most reliably effective channels for B2B marketers.

After the release of its Video Webinar platform, Zoom went dark for over a year. When it resurfaced in February 2015, it was to announce that the company had raised $30 million as part of its Series C round led by Emergence Capital. (Yuan reportedly insisted that every investor present at the pitch meeting at Emergence download the Zoom app so they could join a live video conference of his presentation.)

Zoom’s Series C round was a major step up in the company’s fundraising. The round gave Zoom more than double the entire funding the company had raised to date. Investors weren’t just impressed by Zoom’s technology. They were also impressed by how tightly Yuan ran a ship.

“Zoom is a perfect fit with Emergence Capital’s mission of investing in the cloud visionaries who are building the most important business applications. The company’s explosive growth over the past year shows that they are primed to emerge as the industry’s market leader, and Eric’s key role at WebEx makes him the ideal entrepreneur for this opportunity. Zoom truly is one of the most capital efficient and fastest growing SaaS companies.” — Santi Subotovsky Partner at Emergence Capital

One of the most significant updates to the core product to date came in December 2015, with the introduction of Breakout Rooms. This feature allowed hosts to create smaller groups within a larger meeting. Zoom meetings could already accommodate up to 200 individual participants. With Breakout Rooms, hosts could create up to 50 breakout groups within a single meeting.

Breakout Rooms had major potential in the education market. Zoom had already made significant inroads into academia and was being used by some of the largest universities in the country. The ability for lecturers to break large groups into smaller individual groups lent itself very well to synchronous coursework. But it also had considerable potential for companies working on large projects involving multiple teams. This is a great example of how designing and solving for one audience can create opportunities for other use cases.

In July 2016, Zoom introduced virtual backgrounds to the core product. Now, Zoom meeting hosts could present in front of a green screen using a video-production technique known as chroma key to create the illusion of hosting a meeting from another location. Virtual backgrounds were far from an urgently needed feature. But it did show that Zoom wasn’t averse to developing and introducing fun new features that weren’t essential.

Throughout 2016, Zoom continued to gain ground. Many of the largest and fastest-growing companies in Silicon Valley were already relying on Zoom for everyday meetings and webinars. The company was reluctant to disclose specific figures but reported revenue growth of 300% in 2016.

However, while the tech sector had been a valuable growth vector for Zoom early on, the company couldn’t afford to neglect other markets and verticals. The company needed to get the product in front of entirely new audiences.

That’s when Yuan had an idea.

It’s hardly a secret that Yuan is one of the biggest NBA fans in Silicon Valley. Yuan’s love of professional basketball began shortly after he arrived in the United States, back in 1997, when he first started following California’s Golden State Warriors.

In 2016, Zoom entered into a three-year partnership with the Warriors. Zoom gave the Warriors software to communicate with fans. In exchange, Zoom’s logo would feature prominently during Warriors games at Oakland’s Oracle Arena.

The partnership with the Warriors was one of the first major marketing campaigns the company had ever launched. Sporting-event sponsorships tend to be more effective for branding awareness, but Yuan later claimed this exclusive branding exposure actually helps accelerate sales cycles for the company.

Thanks to strong customer and revenue growth, Zoom ended 2016 in a very enviable position. The company had achieved profitability in Q3 2016. Overall revenue was up 300%, the fourth consecutive year of triple-digit growth for the company. More than 6 billion annualized meeting minutes had been hosted using Zoom. The company was flush with investor cash.

In the coming years, Zoom would prepare for an aggressive push into the enterprise––and one of the biggest IPOs in Silicon Valley history.

2017-Present: Becoming “The Office of the Future

In just six years, Zoom had grown from a scrappy upstart to one of the most widely used web-conferencing products in the world. More than 65,000 companies worldwide were relying on Zoom for meetings, telepresence, and webinars. Over 40 million people had used Zoom to attend or host a meeting. The company had gained more than 2,500 academic customers since 2015, including 90% of the top universities in the United States.

Most importantly, Zoom had achieved all of this by defying conventional wisdom and making a product people genuinely loved, something Yuan had been repeatedly told simply wasn’t possible in the web-conferencing space.

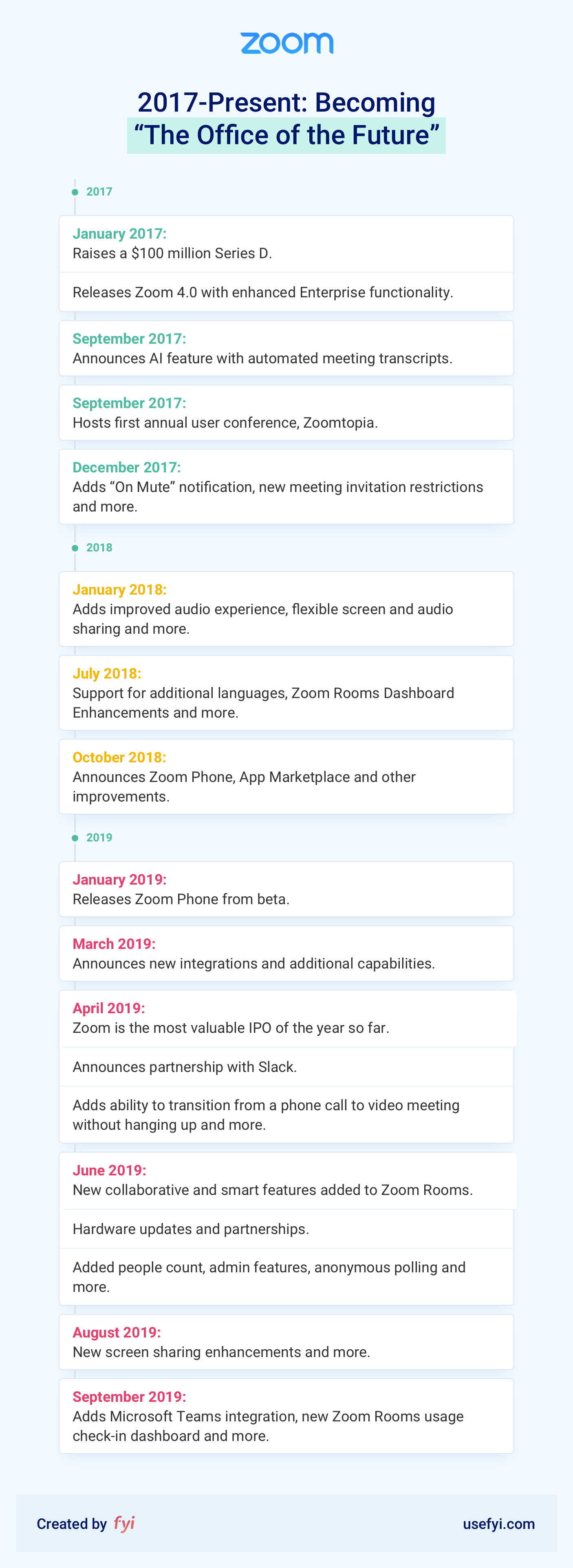

Zoom kicked off 2017 by raising its single largest funding round to date. On January 17, the company confirmed it had raised $100M as part of its Series D round led by Sequoia Capital.

“Zoom has cracked the code for delivering effortless collaboration by providing the first product built from scratch with video in mind. They’re the only enterprise startup that combines Apple-level NPS with Slack-like usage and Facebook-caliber monetization. No other company nails all three. It’s not hard to believe that in 10 years every conference room will be connected by Zoom.” — Carl Eschenbach Partner at Sequoia Capital

Later that month, Zoom launched the fourth major release of the product. Zoom 4.0 featured a range of improvements aimed squarely at the enterprise.

The first was Zoom’s Developer Portal and MobileRTC Platform. Developers could now embed Zoom video into proprietary mobile and web apps. Enhanced meeting controls were added to the Zoom Rooms controller app, which was also made available for Android devices. Voice commands were added to Zoom’s iOS app and the Zoom Rooms controller. Multiple users could now share their screens simultaneously. Meetings now featured “waiting rooms” to give hosts and attendees greater privacy while waiting for meetings to start. Zoom webinars could be broadcast to Facebook Live or directly to YouTube.

In September 2017, Zoom hosted its first ever conference, Zoomtopia, in the Bay Area. The event featured a range of sessions and panel discussions on a broad range of topics, such as how companies could build a video-first culture and what the offices and classrooms of the future might look like. The inaugural Zoomtopia conference was also where the company decided to unveil several exciting features that offered attendees a glimpse of Zoom’s future.

The first was Zoom’s nascent augmented reality (AR) features. Speaking about the technology, Yuan said that Zoom’s new AR technologies would soon make interactive learning even more immersive. Another significant update announced at Zoomtopia was the product’s new automated transcription feature. Using machine-learning, Zoom’s automated transcription feature analyzed audio recordings of meetings, identifying each individual speaker, before transcribing them automatically.

Zoom not only wanted to be the best video-conferencing tool in the enterprise; it also wanted to be at the very heart of the office of the future. Zoom wasn’t just building a better way to communicate. It was eliminating much of the day-to-day friction millions of workers experienced every day. Thanks to Zoom’s tight integrations with Slack and Outlook, meetings could be scheduled and held from virtually anywhere on any device. The product’s new AR and machine-learning features had vast potential in the education and health care sectors. The product’s modular approach to feature add-ons and affordable pricing meant even small companies could benefit from Zoom without being forced to pay extra for features they didn’t need.

Zoom kept the feature updates coming in late 2017, when the company announced several new features in December. The first was an on-mute notification that let meeting attendees know if they began speaking while still muted. Zoom improved its virtual backgrounds feature to look more convincing in low-light conditions. Users could now choose whether to include thumbnail videos during screen-share portions of recordings. Time stamps could now be added to recordings. Finally, hosts could restrict invitations to specific domains when scheduling a Zoom meeting, something that could formerly be done only via Zoom’s admin portal.

Even though Zoom had begun to scale, the company remained tightly focused on improving the product. A valuable lesson Yuan had learned during his time at WebEx.

After an update following Zoomtopia in late 2017, Zoom went quiet until the summer of 2018. In June, Zoom improved on several aspects of the core product. Users could now join audio meetings much more quickly, and the audio quality itself was improved significantly. The product’s sharing options were tweaked to give users more control over how much of their screen was shared. Side-by-side recording playback was added. Archiving, screenshot annotation, and a new “Away” status indicator were added to Zoom Chat. Zoom’s iOS and Android apps were integrated more tightly with users’ calendars. A public Q&A feature was added to Zoom Video Webinars.

Zoom kept its foot on the gas in the summer of 2018 with even more updates to Zoom Rooms in July. A check-in reservation system was added to Zoom Rooms to give users greater control over meeting scheduling. Zoom Rooms could now be branded with customized backgrounds. Support for French, German, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish was added to Rooms. The Zoom Rooms controller was updated to support new presets for two Logitech pan-tilt-zoom (PTZ) cameras. Zoom Rooms now natively supported calls made via Polycom’s Trio conferencing phones. Finally, the Rooms dashboard was improved to display the “Health Status” of meeting rooms, such as the strength of wireless connections and the status of networked devices.

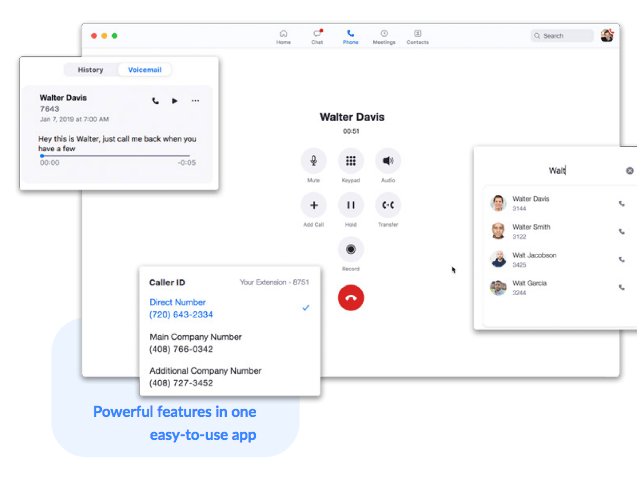

Most of Zoom’s updates in 2018 focused on improving existing products. That changed in October, when Zoom unveiled Zoom Phone.

Zoom Phone, which was initially called Zoom Voice, is a cloud-based phone system that complements the Zoom platform designed to replace private branch exchange (PBX) phone systems. Zoom Phone allows large companies to import their existing public switched telephone network (PSTN) system configurations without porting numbers or canceling existing service contracts.

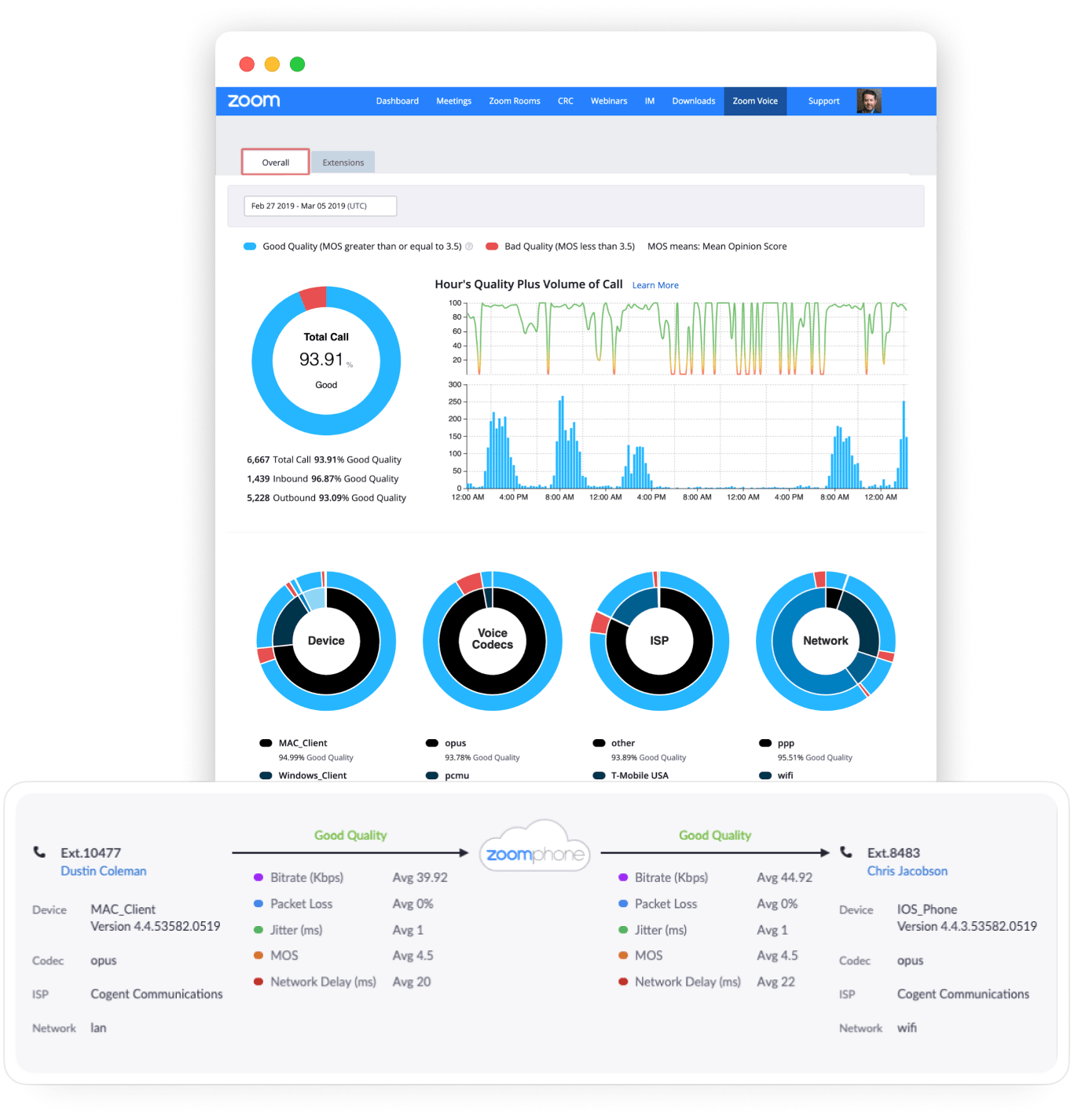

The ability to seamlessly upgrade to a cloud-based phone system optimized for enterprise clients was a smart, bold play. Now, Zoom could offer Enterprise firms end-to-end telephony services without the need for new hardware, disruption in phone service, or migration of existing phone numbers. In addition, Zoom Phone’s detailed analytics dashboard gave administrators unprecedented insight into the status and performance of their communications.

Zoom Phone wasn’t the only major update the company shipped in October 2018. Zoom also launched its App Marketplace that month. Zoom had offered an API and several SDKs since 2016. But the App Marketplace took integrations with Zoom to a whole new level. Apps and add-ons were categorized by type, such as Assistants, Scheduling, and Security & Compliance. Zoom partnered with several major tech companies to provide apps and bots from HubSpot, Microsoft Teams, and Slack, among many others.

By 2019, Zoom was dominating the B2B video communications space.

Not so long ago, Zoom was the underdog. Now, major hardware manufacturers such as Dell, Logitech, and Polycom were making devices that were optimized for Zoom Rooms. The core product had received dozens of updates, each of which made Zoom increasingly valuable to enterprise clients.

Zoom’s initial focus had been reliability. Now, Zoom was focused on interoperability.

Despite his company’s amazing growth over the past several years, Yuan wasn’t content to take his foot off the gas. Throughout 2019, Zoom has made even more updates to the product. January saw the Zoom Phone system formally exit beta and several new apps were added to the App Marketplace. In March, the Zoom Phone was updated to allow users to seamlessly transition from a Zoom Phone call to a Zoom Meeting without dropping the call.

March also saw the introduction of several exciting new machine-learning features to the core product. Real-time transcription support was added to Meetings. Zoom announced that, as of Q3 2019, simultaneous real-time translation services would be supported. Zoom now captured recorded meeting minutes as an automated summary, complete with action items. The company announced an even tighter integration with Microsoft Teams, which was scheduled for release in Q2. Users could even schedule meetings via Apple’s Siri.

It’s hard to understate how potentially disruptive Zoom’s machine-learning features could be in the near future. The product’s real-time transcription function is impressive. But accurate real-time translation between multiple meeting participants reveals just how sophisticated Zoom’s underlying technologies really are.

Zoom is no longer just a web-conferencing product. It’s a video-enabled workspace platform.

By the spring of 2019, speculation about Zoom’s inevitable IPO had reached a fever pitch. And, on April 18, the company finally went public.

At the conclusion of Zoom’s first day of trading on the Nasdaq, Zoom’s stock was trading at $62 per share which was up 72% on analysts’ projections. This gave Yuan’s company an initial valuation of almost $16 billion.

Many analysts were understandably preoccupied with Zoom’s profitability. Given how few companies achieve profitability before going public, this was a predictable reaction to Zoom’s stellar first day of trading. But the focus on Zoom’s profitability misses the point about Zoom as a company entirely.

Yuan never set out to build the world’s most profitable web-conferencing company. Yuan wanted to build the world’s best web-conferencing product. He did so by applying an engineering mindset to how he built his company. Yuan ran a tight ship and focused entirely on the product because he cared deeply about the experience of using the product. Ever since his days at WebEx, Yuan had felt a deep, personal responsibility to provide the best possible experience for his customers. It’s what prompted him to quit a corporate VP position managing 800 people to launch his own company out of a tiny office in Santa Clara. To Yuan, his product was his company.

Everything else was secondary, including profitability. Although the tech press was technically right that Zoom’s IPO was “the most valuable” of the year, much of the coverage focused on Zoom’s financial value rather than the immense potential value of the product itself.

Unlike Google, Microsoft, and seemingly every other major tech company, Zoom wasn’t competing directly with Slack. Zoom’s Slack integration had been in place since 2015, and the two companies have worked closely with one another ever since. Shortly after the company’s IPO, Zoom announced even deeper integration between Zoom and Slack.

Now, users could see more information about Zoom meetings scheduled via Slack, including confirmed attendees. Zoom Phone calls could be now be made directly within Slack. Users could receive notifications from both Outlook and Google Calendar as Slack notifications. These weren’t the biggest updates, but they were solid quality-of-life improvements that made working with Zoom even more seamless.

Between April and September 2019, Zoom made dozens more improvements to the product. In April, users gained the ability to block specific contacts and disable Zoom’s chat feature. Meeting participants could be renamed. The UI layout could be customized. April also saw the introduction of a consent feature that allowed users to agree or decline for their meetings to be recorded by hosts.

June saw a number of improvements made to Zoom Rooms as well as to the core product. Thanks to Zoom’s machine-learning technologies, Rooms now counted the number of meeting attendees automatically and updated its new in-room person counter accordingly. Chat panes were now visible from Rooms. Zoom Rooms for Touch received a number of improvements, including automatic shape-detection and pressure sensitivity.

Although many of the updates made in 2019 focused on the company’s software products, Zoom wasn’t ignoring its emerging hardware business. In late June 2019, Logitech released its Room Solutions for Zoom Rooms hardware line. These devices come in preassembled kits that can be set up in a conference room right out of the box. Hardware manufacturer Crestron also released kits for Zoom Rooms. PC manufacturer Lenovo also debuted its ThinkSmart Hub 500, an integrated mic/speaker/controller for Zoom Rooms that summer.

Late June 2019 also saw the rollout of several improvements to Zoom’s dashboard reporting. The number of active participants in a Zoom Room could now be seen in the Zoom dashboard and exported as a CSV file. International time zones and anonymous polls were added to the core product. Most significantly, administrators now had access to 12 months of analytics data instead of just one month. This gave admins greater insight into how their teams were using Zoom over a statistically meaningful period of time.

The summer of 2019 was one of the busiest in the product’s history in terms of updates. However, Zoom’s frantic pace of feature development took a backseat in July 2019, when the company was rocked by news of a zero-day security exploit in Zoom’s OS X code.

The exploit relied on how Zoom works at the local level on Macs. To make Zoom calls feel as seamless as possible, Zoom creates a local web server on every Zoom user’s Mac. Zoom originally claimed this architectural design choice was necessary due to changes Apple made to Safari 12. The change would have forced users to manually approve Zoom every time they clicked on a call link. But Zoom’s decision to install a local web server on every user’s machine also created a significant security vulnerability. Users could be tricked into joining a Zoom meeting by a malicious actor, at which point the user’s video feed would be openly visible to the attacker.

In a statement issued shortly after the vulnerability was publicized, Zoom defended its decision. But the researcher who discovered the exploit, Jonathan Leitschuh, was skeptical. Leitschuh later declined a financial reward offered by Zoom due to the nondisclosure agreement attached to the bug bounty. He also advised other researchers to report similar vulnerabilities via the Zero Day Initiative rather than reporting exploits to Zoom directly in light of how the company responded.

“Let me start off by saying having an installed app that is running a web server on my local machine with a totally undocumented API feels incredibly sketchy to me. Secondly, the fact that any website that I visit can interact with this web server running on my machine is a huge red flag for me as a Security Researcher.” — Jonathan Leitschuh

In the grand scheme of things, Zoom’s security vulnerability wasn’t as catastrophic as it could have been. Zoom genuinely had its customers’ interests in mind when it made the decision to install local web servers on customers’ Macs. But even well-intentioned decisions can have unintended consequences, especially if you’re moving as fast as Zoom was.

After releasing some minor updates to screen-sharing and Breakout Rooms in August, Zoom updated the core product again in September 2019. More than 20 updates were made to the Zoom Phone system alone. These included improved analytics, automatic call recording, support for multiple lines, shared voicemail, and a dedicated Linux app, among others.

The September 2019 update also saw a number of improvements aimed at enterprise clients. Administrators could now enable password protection to all meetings. Zoom’s integration with Microsoft Teams was updated to allow users to start or join Zoom meetings with just one click. Finally, Zoom made an additional 30 specialized APIs available to developers.

Zoom is, at its core, an engineering-focused company. At every stage of the company’s growth, product has been the central focus. Eric Yuan didn’t just want to build the best web-conferencing product in the world. He wanted to build a web-conferencing product that people genuinely loved to use and he did it by focusing relentlessly on product.

Zoom’s biggest challenge moving forward will be how to maintain the pace of rapid growth Zoom has experienced thus far. As Zoom proved, a superior product can make a big impact in a crowded market but it’s much harder to maintain strong growth once you’ve dominated that market.

Where Could Zoom Go from Here?

Zoom has quickly become the de facto gold standard for video conferencing and real-time collaborative communication. Where could Zoom go from here?

- Much greater emphasis on augmented and virtual reality. Both AR and VR have been popular in the consumer space. Zoom’s nascent AR and VR functionality are both likely to feature in the product more significantly in the near future. Zoom’s roots as an engineering-driven company could be a considerable asset as technologies in this space advance. As AR and VR technologies mature and become commonplace, Zoom is likely to be at the forefront of these advancements in the B2B communications vertical.

- A considerable overhaul of Zoom’s UI/UX. Despite being a much more technically sophisticated product at launch, Zoom’s UX is relatively utilitarian. Both the actual design of Zoom as a product and the experience of using it draw heavily on products that Zoom improved upon. In the future, we’re likely to see Zoom make significant improvements to the product’s interface and UX to differentiate itself from competing products and provide an even better experience for users.

- More investment in hardware products. The web-conferencing vertical has moved away from hardware- and room-based solutions. But these products still offer potential value to certain markets, particularly in the enterprise. Now that Zoom has become the go-to software standard in web conferencing, it stands to reason that Zoom could feasibly diversify into additional hardware products. This seems particularly likely in the context of Zoom’s emerging AR and VR technologies, both of which currently rely primarily on consumer-focused devices.

What Can We Learn from Zoom?

The origin story of Eric Yuan’s journey from Shandong Province to Silicon Valley is as inspiring as it was improbable. What can other founders learn from Yuan’s experiences?

1. Understand your market intimately. Eric Yuan was the man for the job of reimagining web conferencing. He’d been envisioning the future of video communication for more than 20 years before starting his company. He understood that the key to winning in the web-conferencing space wasn’t extra features––it was reliability. Make sure you really “get” the market you’re targeting. Understand what customers really want and the problems they face.

Think about your industry and your product’s place within it:

- What made you choose the target market you chose? Did you choose this market due to your familiarity with it, or because you identified an urgent problem in need of a solution?

- What aspects of your core market(s) could you understand better? How might you go about deepening your understanding of the problems prospective customers in this market experience?

- What steps are you taking right now to mitigate potential threats to your position in your core market? How are your competitors preparing for these potential threats?

2. Identify a core market and target that market tightly. Early on, Zoom recognized education and health care as two primary markets in which Zoom could have an immediate, significant impact. The company could have feasibly branched out into tangential markets much earlier. But doing so could have jeopardized the company’s favorable position in the education and health care verticals by spreading the company’s limited resources too widely. Before launching your product, identify one or two core markets, and focus your initial efforts on dominating those markets before expanding.

Consider your company’s growth goals for the next year or so:

- What’s the single greatest risk factor or challenge you’re likely to face in your existing market over the next year? How are you planning to overcome that challenge?

- How easily could you branch out into a tangential market from your current position? What steps would you need to take over the next 12 months to do so?

- If you did expand into a tangential market, how would you maintain your current standard of customer support while expanding into a new vertical?

3. Innovate by aligning your product with what customers really want. Zoom has been able to aggressively expand its feature set by relentlessly focusing on the needs of its customers. The company has then been able to improve on those features incrementally to consistently provide greater value. Don’t just settle for solving a problem, solve the problem, then innovate by iterating and improving upon on that solution.

Take a look at your product roadmap:

- How many of the feature releases or updates you have planned for the next 12 months will genuinely help your customers solve their problems more effectively? How many are smaller quality-of-life improvements?

- If you had unlimited resources, what’s the biggest step you could take to fundamentally improve the experience of using your product or its core functionality? How could you begin implementing this feature with the resources you have?

- How are you listening to your customers? Are you conducting regular customer interviews and surveys? What commonalities have you identified in this feedback, and how do you plan to act upon it?

Bringing People Together

It’s tempting to say that Zoom almost single-handedly reshaped the web-conferencing vertical in just eight years. But, in reality, Eric Yuan has been obsessed with video conferencing for more than 30 years. Zoom succeeded in a crowded, competitive space because it was a superior product. But it also succeeded because nobody cared about improving web conferencing more than Yuan did.

Zoom is a great example of a bold company led by a true visionary. It’s also a great example of what happens when you identify an urgent problem in need of a solution and focus on that solution to the exclusion of everything else. Zoom has accomplished in eight years what rival companies failed to do in twice that time. The real questions now are what Zoom will do next and what those once-seemingly unbeatable rivals will do to keep up.