Why Trello Failed to Build a $1 Billion+ Business

In 2011, Joel Spolsky launched his company Fog Creek’s new product at TechCrunch Disrupt called Trello. It looked a lot like a whiteboard with sticky notes translated into a web browser and an iPhone App. Instead of physically moving a sticky note on a whiteboard, you could drag and drop cards on a board from your web browser.

Within days, Trello succeeded in getting 131,000 eyeballs. 22% of them signed up. The vision for Trello was to create a wide product that was so simple and useful, just about anyone could use it. It caught on like wildfire.

It’s also why Trello ultimately had to sell to Atlassian for $425 million when it could have become the next $1 billion SaaS application.

In a blog post Spolsky wrote a couple months after launch, Joel presciently touched on the biggest challenge ahead:

“Making a major horizontal product that’s useful in any walk of life is almost impossible to pull off. You can’t charge very much, because you’re competing with other horizontal products that can amortize their development costs across a huge number of users. It’s high risk, high reward.”

Trello was successful building this horizontal product, achieving rapid growth to tens of millions of users and an acquisition of hundreds of millions of dollars. However, the one thing Trello didn’t do a good job of was keeping track of it’s paying customers.

Trello was so focused on building its free customer base first and monetizing later; by the time it looked to its paid subscribers, it was too late—they’d already moved on. While that makes Trello a perfect complement to Atlassian’s suite of enterprise productivity tools, it hampered the company from growing further on its own.

Let’s talk about the opportunity that Trello missed, and what it could have done instead.

Why Trello Had to Sell

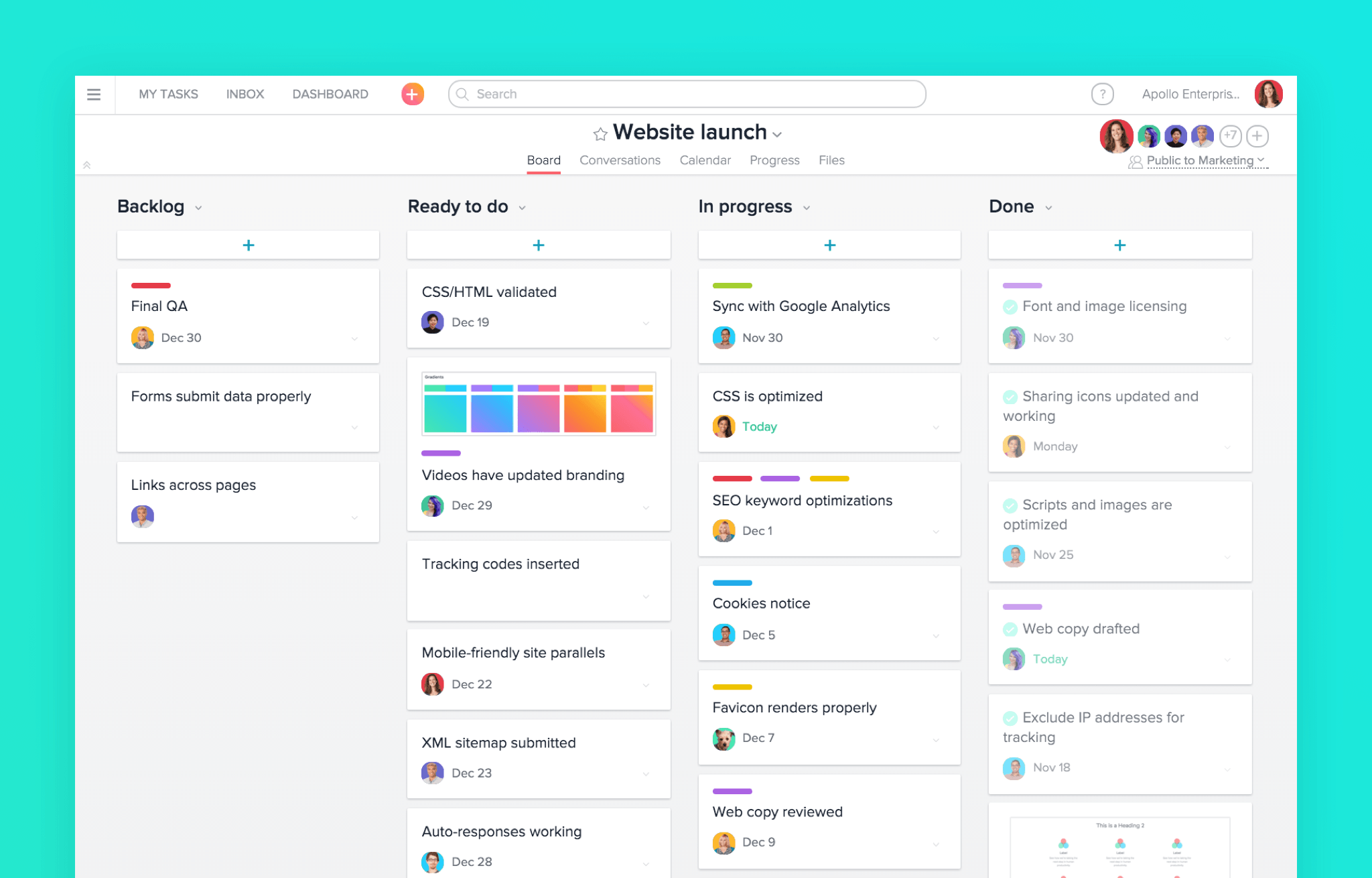

Trello is organized around a “kanban board” concept. Kanban was a system for lean manufacturing that Toyota popularized in the 1940s. The basic idea was that each “card” represented a product, part, or inventory. When a card moved around a board, it meant that something had been physically moved from a supplier to a factory.

In practice, it looks like this:

When Trello first started out, it was really technically challenging to create a board in a web browser where you could collaboratively drag and drop cards into lists. A lot of other SaaS tools at the time were big databases with a visual interface built on top (think: Salesforce). This basically created an architecture where you structured data in terms of leads, customers, or tasks.

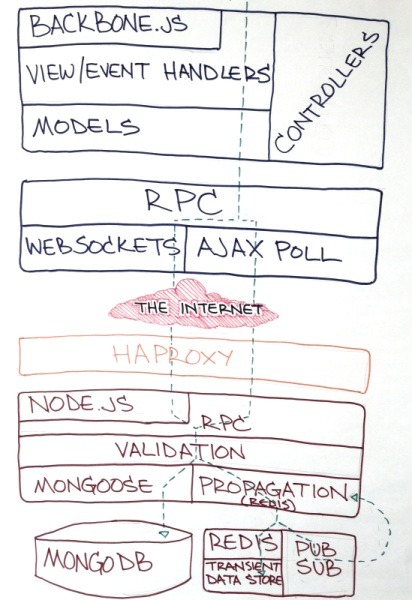

Trello came at this from the opposite direction. The product vision was to strip everything down and build around the visual idea of cards on boards. To get this to work, Trello implemented a bleeding-edge stack. The single page web app basically worked as a shell that pulled all of the data from the servers in less than half a second, at under 250 kilobytes. After a user visited for the first time, they then cached the page so Trello would load even faster.

They built their servers on top of Node and used MongoDB to store data so that the web app would load really fast. Everytime a user dragged a card to a new list, or changed the entry on a board, Trello pushed this data to every other browser with the board open almost instantly.

The result was breathtakingly simple. You made a change to a board by dragging and dropping a card, and that change was reflected everywhere else in the world.

All of this stuff was new at the time, and gave Trello a lot of runway. But by 2016, it wasn’t as hard to a build beautiful and responsive web app like Trello, and you started seeing Kanban boards everywhere:

- GitHub builds Kanban boards in September 2016:

- Asana announces Kanban Boards in November 2016:

- Airtable Launches Kanban Boards in November 2016:

Justin Rosenstein, co-founder of Asana—one of Trello’s biggest competitors—said, “We definitely give Trello full credit. That is clearly the product that has done a good job pioneering this view.” But Justin was equally unapologetic about copy-catting Trello’s board feature: “We see Trello as a feature, not a product.”

Trello might have become a $1 billion+ business if it looked like a “system of record” application—the single-source of truth for a company. Imagine if you could use Trello not just to track your marketing funnel, but to move information from your marketing board to your sales pipeline and product roadmap. Instead of having a separate Trello board for each team, you’d have a big board for the entire company.

Trello never became this “system of record.” It was a strong visual metaphor that the competition ultimately copied. The Kanban board turned out to be a really cool UX feature, but not a difficult one to replicate.

In SaaS, you don’t win by getting there first or having the best idea. You win by continually solving the problem better. When you build a feature that’s extremely popular or successful, the competition will steal it.

Trello could have doubled down on upselling individual consumers to paid plans. They could have focused on building features for SMB customers. Or they could have expanded into the enterprise faster. Any one of these things would have led to a $1B+ valuation. Let’s talk about what Trello could have done with each path, starting with its consumer plan.

#1) Trello Didn’t Monetize Free Fast Enough

It’s possible to build a $1B+ company with a freemium business model targeted toward consumers. In 2013, Dropbox was valued at $8B on $200M in revenue with 200M users six years after launch. This was before Dropbox had even launched a business plan—the company’s revenue primarily came from upselling free users to a $10/month plan.

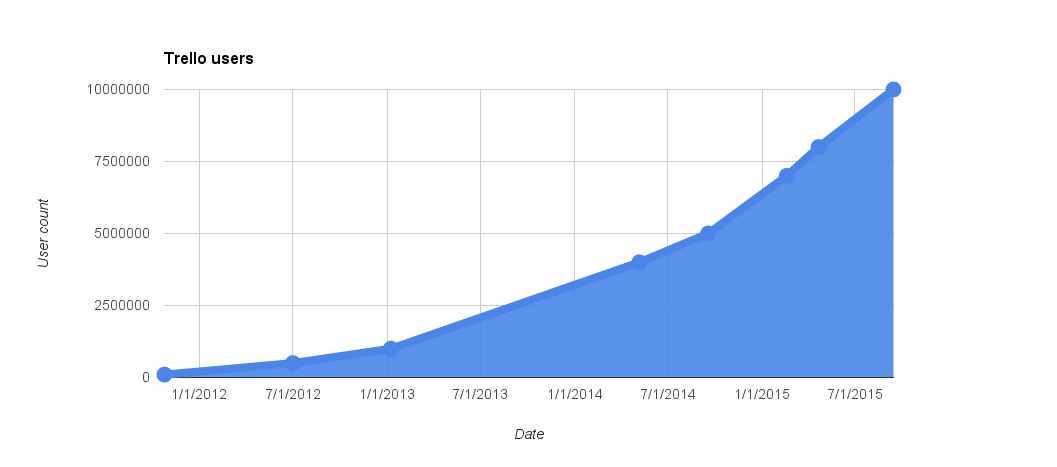

Three years after launch, Trello’s growth in users looked on track to explode past Dropbox’s levels, at 10 million in 2015 (Dropbox had four million three years after launch). But Trello had a much harder time upselling free customers to its paid “Trello Gold” plan.

The 2013 blog post that announced the launch of Trello Gold highlighted three main reasons users should pay $5/month for Trello:

- Customizable board backgrounds

- 250-megabyte attachments for each card in Trello (vs. 10 megabytes on the free plan)

- Stickers and custom emoji

While everyone likes emojis, it’s not a good enough reason to spend money on software. Dropbox’s free plan gives away 2 GB of space. Its paid plan delivers 1TB of space—50x what users get for free.

Trello’s value proposition is harder to locate than Dropbox, which is exactly why Trello should have figured out early what features individual consumers were willing to pay for.

Solution: Dig Into the Freemium Use-Cases

Instead, Trello focused on building a freemium, horizontal product that everyone could use, and chose to figure out monetization later.

Instead of focusing on building a wide product for everyone, Trello should have dug deeper into its use cases in the beginning to figure out why people were signing up, what they were using the product for, and what people found so valuable that they’d be willing to pay to use Trello.

If you have a broad product with a lot of applications, dive into all of the different use cases first:

- Is there a competitor that’s able to do this—or is already doing it today?

- What’s the revenue potential for people using this use case?

By doing research around your customer base and your competitor’s customers, you can segment out the use cases with the highest lifetime value.

Let’s say Trello found out that of its freemium user base, lawyers, real estate agents, and designers had the highest revenue potential. They might have learned that while designers want access to a calendar in their Trello boards, lawyers want read-only boards that they can share with clients.

These were features that Trello already included in its business plan, but didn’t emphasize in its marketing because they wanted to keep a wide focus. Instead, Trello could have created a separate landing page to re-target free customers and upsell them to a paid plan according to their specific use cases.

When you have a wide product, it’s especially important to dig into the individual use cases for your product, because it allows you to build specialized features according to those verticals. If you don’t want to build your business off of a freemium consumer product, you have options—you can move up the ladder and build around SMBs.

#2) Trello’s Product Wasn’t Sticky Enough for SMBs

Even without a really valuable consumer business, Trello still could have become the default workflow tool in SaaS by doubling-down on the SMB market. The problem was that Trello didn’t always make itself central enough to a company’s workflow to justify paying for it by the seat.

The first paid plan that Trello launched was its Business Class for small-to-medium sized businesses in 2013. They charged a flat rate price of $200/year per organization before moving to a more traditional per-seat SaaS pricing model.

Trello Business Class costs $10 per user/month (billed annually) and you get:

- Unlimited integrations across boards

- Additional collaboration features

- Read-only views and privacy settings

When David Cancel, co-founder of Drift, put the company’s annual Trello bill on a slide—$1,700—the entire team at Drift was shocked. As David says, “There are only a couple of people using [Trello] day-in, day-out. Meanwhile, however, we were being charged based on the number of people that we had in the paid plan. So clearly there was a disconnect between the price we were paying and the value we were getting.”

David downgraded his team from the paid plan to the free plan.

In a Forbes article Trello CEO Michael Pryor said: “I don’t want people to spend 10 hours in Trello every day, we don’t sell ads so we don’t do better engaging more of your time like a social media platform.”

That’s okay. When you’re charging SMBs by the seat, you don’t have to optimize your product around getting users to log in more. But you have to find some other way to demonstrate the value of paying for your product across the company.

So, what should Trello have done instead?

Solution: Build Out Better Integrations for SMBs

Trello could have created a stickier business product by making sure that it was so deeply integrated with other tools, teams couldn’t rip it out.

Imagine the ability to open and close GitHub issues inside of Trello. Imagine if all of your Salesforce leads automatically opened and closed on a Trello board based on what you did inside of Salesforce. Trello would have become the dashboard for all of the other tools a company used—something that would have been insanely valuable.

Instead, Trello’s main features were copy-catted. When asked about building out boards for visually managing issues, GitHub’s VP of Product Engineering explained that: “Everyone was expecting it to be there and asking questions about why we didn’t have it.” So GitHub built boards.

If you’re building a horizontal SaaS app like Trello, segment your users by integration:

- What API integrations are people using?

- How much data is coming into the product and how much is going out?

That gives a valuable lens into another type of use case for your product. If a lot of data is pouring from your product to a different one, it’s a sign that the competition is heating up. By building out better integrations and new product features, you can pre-empt the competition from stepping on your turf.

The SaaS SMB market is hyper-competitive, and it’s easier than ever before for businesses to switch from one solution to another. You either have to outmaneuver the competition, or build staying power by moving upmarket to the enterprise.

#3) Trello Didn’t Build for the Enterprise

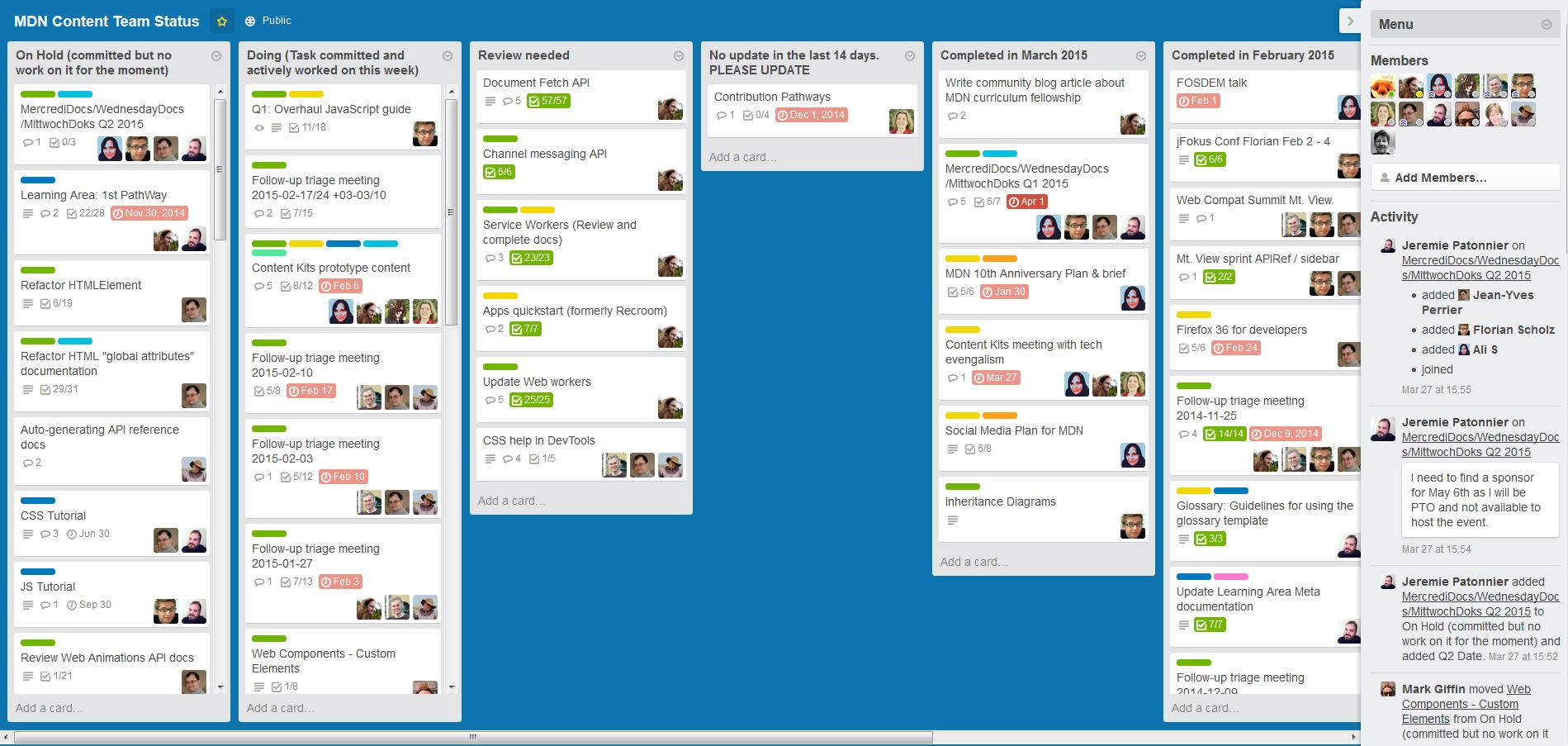

Moving upstream and targeting the enterprise market is a proven model for SaaS. Slack is doing it with the launch of its Enterprise Grid. Trello could have built a $1B+ business by doing the same: moving into the enterprise market faster.

Less than a year after Trello launched its enterprise sales strategy in 2015, the company hit a milestone of $10 million in ARR. In an interview, Trello’s VP of Sales, Kristen Habacht writes that Trello follows a pretty basic land-and-expand enterprise sales strategy:

“For our enterprise team we’ll look at [customers] who have really high Trello user counts. A lot of our outbound sales strategy is just reaching out to those accounts and saying, “Hey you have 2,000+ people on Trello, who can we talk to about that?”

$10 million in ARR isn’t anything to sneeze at. The problem with Trello’s enterprise sales strategy is that it was only built on top of the reality that people in a company were already using Trello. A company’s sales, marketing, and product teams might each use a bunch of different Trello boards. But what’s harder is organizing the entire company around Trello.

Solution: Become the System of Record for the Enterprise

The question that Trello should have been asking itself is, “How do we integrate with higher-end systems that larger companies are using and make ourselves indispensable to companies by becoming a core part of their workflow?”

One way to do it is to take the Slack strategy. As Slack grew, the company was razor-focused on how it spread from individuals, to teams, to entire companies—catching like wildfire.

The big challenge that Slack found is that unlike a sales CRM or a marketing analytics tool, almost everyone on a small team has veto power over a productivity tool. So, Slack spent six months in private beta observing their customer base and educating them around the need for an internal communication tool in the first place. They optimized their onboarding flow around a north star metric of 2,000 messages sent within an organization. Today, 93% of those companies are still using Slack.

The vision behind Slack’s enterprise product is that it allows organizations to “create more or less any kind of structure” with Slack. Functionally, Slack is a different product for the Enterprise. Teams within a company can organize themselves into “workspaces” and form divisions according to their organizational structure. Because Slack was so focused on figuring out how and why its product spread from small teams, to departments, to larger organizations, it was able to pinpoint key problems for the enterprise and solve them with the Enterprise Grid.

Large enterprise companies love flexibility and configurability. Like Slack, Trello could have carved out a seat at the enterprise table by allowing large companies to configure Trello to their organizational charts. Trello’s advantage is that it’s already an extremely versatile and easy-to-use product. By providing companies structure between departments, Trello might have worked as the connective tissue holding a company together.

Congratulations, Trello

Hindsight, of course, is 20/20. While I’ve spent most of this post talking about Trello’s missed opportunity, we shouldn’t forget that building a SaaS business that’s worth over $10 million, let alone one that’s worth $425M, is a huge accomplishment.

Trello and the team at Fog Creek paid for Trello out of pocket. Trello has been a huge success since the moment Joel launched it at TechCrunch Disrupt. The team grew it to 500,000 users within two years, and 4.75M users within four years—before raising any money. They built an amazing product that was way ahead of its time. It was simple, elegant, and easy-to-use.

A couple months ago, I tweeted:

That’s the impact that Trello has had on SaaS, and you see it everywhere, from GitHub to Jira.

But if you want to build the next $1 billion+ SaaS app, you have to remember to constantly evolve on top of your product. Don’t build around any one single feature that the competition can rip out. Alternatively, make that one single feature so deeply integrated into everyone else’s product that it’s pointless for anyone else to copycat it.

Above all, you need to go deep into understanding who your customers are early on, because that’s how you’ll know what to implement into your product and where to take it next. Doing the research and the hard work is the only way to keep your product relevant in the market.