The Most Important Turning Points in Microsoft’s History

With the possible exception of the earliest pioneers of Silicon Valley, such as IBM, Xerox, and Bell Labs, it’s hard to think of a company that has had a more profound, lasting impact on the world of technology than Microsoft.

However, despite its role in fundamentally shaping the landscape of modern computing, Microsoft has an undeserved reputation as a boring company that makes boring products. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Microsoft’s journey from a scrappy, opportunistic startup in New Mexico to a global corporate software giant is a fascinating story of ambition, power, and hubris.

Here are a few of the things we’ll be looking at in this article:

- Why Microsoft’s history of focusing on quantity, not quality, has worked incredibly well

- How Microsoft ruthlessly pursued market share at any and all costs

- How Microsoft’s relentless focus on “a PC in every home” almost destroyed the company

To understand Microsoft’s approach to product, we need to first understand the ideologies that shaped the company during its earliest days and how this drove Microsoft’s approach to growth. Like another Silicon Valley success story, that tale began in a Harvard dorm.

1980-1999: Building a Monopoly

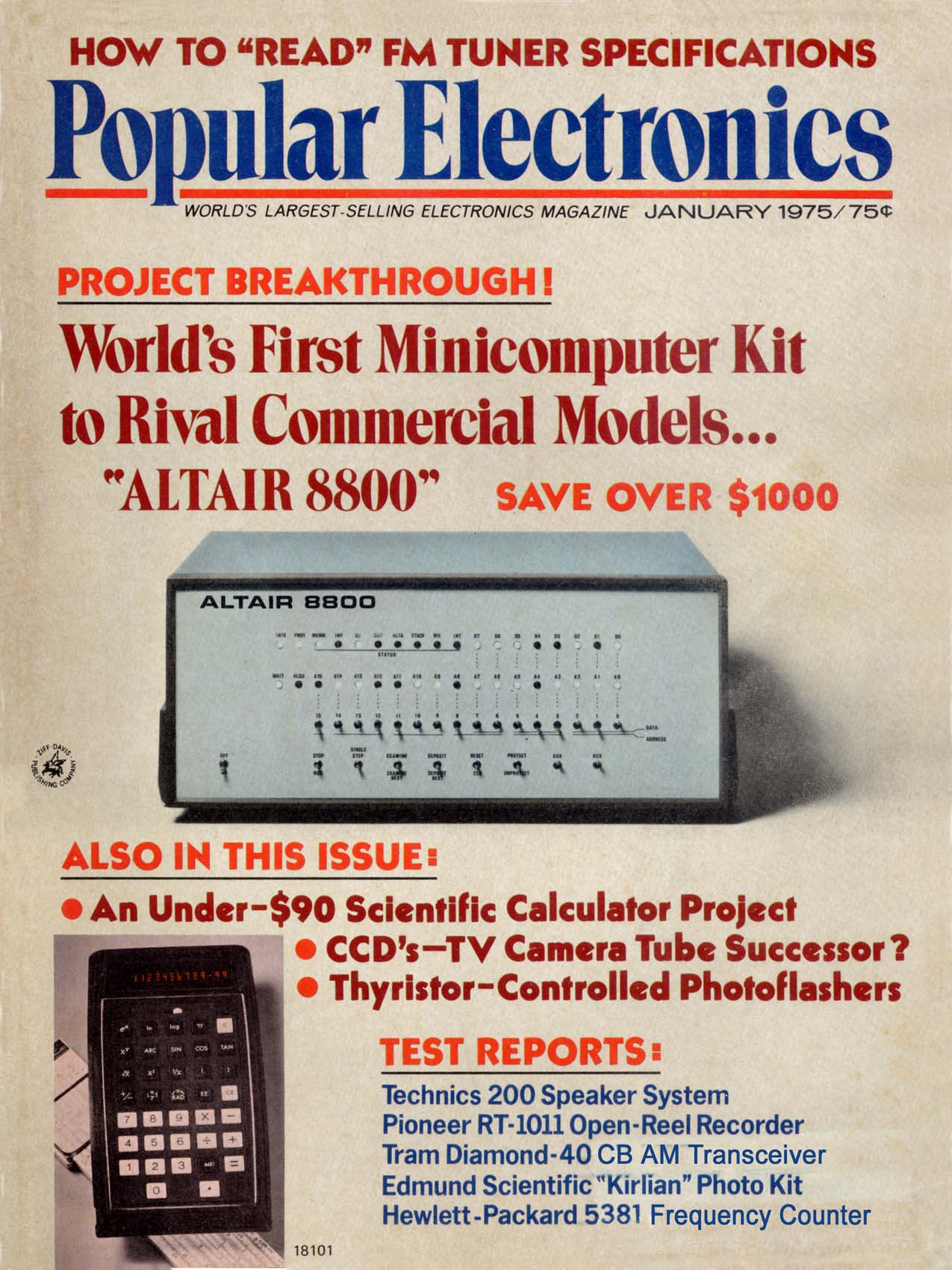

In 1975, 22-year-old computer programmer Paul Allen got his hands on the January issue of Popular Electronics magazine. The cover featured an image of the “World’s First Minicomputer Kit to Rival Commercial Models,” the Altair 8800 microcomputer.

The magazine’s cover feature had given Allen an idea. With his copy of Popular Electronics in hand, Allen visited his childhood friend and fellow programming enthusiast, Bill Gates, at nearby Harvard University in Cambridge. Allen and Gates had been friends since their days at Lakeside School, a private preparatory school in Seattle, Washington, where the two boys had spent hours learning the intricacies of the school’s Teletype Model 33 ASR terminal and a huge, bulky General Electric mainframe.

Gates had been fascinated with computers since before grade school. As he learned—then mastered—a number of languages including FORTRAN and LISP, Gates flexed his programming muscles by modifying the code of a class scheduling program at Lakeside that placed Gates in classes with “a disproportionate number of interesting girls.” Gates and Allen became such accomplished programmers, they were hired by Information Sciences, Inc., to write a payroll program for the company in COBOL in 1971 when Gates was just 16 years old.

Allen’s idea was to adapt the Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code—better known as BASIC—programming language for the Altair 8800. At the time, Allen was working at Honeywell, Inc., in Boston, while Gates was pre-law at Harvard after spending the previous summer alongside Allen at Honeywell. Allen successfully persuaded Gates to leave Harvard to pursue his business idea.

The Altair 8800 was a revolutionary machine. However, like many microcomputers of the age, the Altair 8800 lacked an interpreter, computer programs that executed the source code provided to them by the machine’s compiler. Allen’s idea to develop an interpreter built using BASIC was clever. A dedicated interpreter for the 8800 would make the microcomputer more appealing to hobbyist programmers like Allen and Gates. As Allen correctly predicted, it would also drive down the costs of microcomputers to the point at which developing commercial software for these machines would be a viable, profitable business. This was the real brilliance of Allen’s idea.

In March 1975, Allen and Gates contacted Ed Roberts, founder of Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS), to offer him an in-person demonstration of their BASIC interpreter for the 8800. Roberts agreed, and Gates flew to MITS’ headquarters in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to present their interpreter. Roberts was impressed and agreed to distribute Altair BASIC.

On February 1, 1975, Allen and Gates sold their code to MITS for $3,000 (around $14,000 in 2018 dollars), plus a percentage of royalty payments up to $180,000 (roughly $843,000 in 2018 dollars). Allen and Gates formally registered their company name—then known as Micro-Soft, a hyphenated portmanteau of “microcomputer” and “software”—in 1976, and formally incorporated the company in New Mexico the following year.

Allen’s instincts had been right on the money. Micro-Soft’s 8800 interpreter was immensely popular with programming enthusiasts and computer hobbyists. By the end of 1976, Micro-Soft exceeded $16,000 in revenue, roughly $71k in 2018 currency. Just two years later in 1978, the newly rebranded Microsoft exceeded $1M in annual revenue thanks to the popularity of the 8800.

As the growing company’s need for skilled programmers increased, Allen and Gates made the decision to relocate from New Mexico to Washington State, having found it difficult to recruit skilled programmers in the Southwest. Microsoft officially opened its headquarters in Bellevue, Washington, on January 1, 1979. That same year, Gates negotiated an agreement with Kazuhiko Nishi and Keiichiro Tsukamoto to open Microsoft’s first international sales office in Japan, ASCII Microsoft.

Microsoft had leveraged an incredible business opportunity to essentially create an entirely new category within the nascent computing industry. However, the company’s big break wasn’t its initial agreement with MITS to develop its interpreter for the 8800, but rather, a similar agreement with IBM in 1980—a partnership that would propel Microsoft from a niche software development company to a household name.

Similar to the MITS deal, Microsoft was contracted to develop an operating system for the forthcoming IBM PC Model 5150 home computer. IBM had expressed interest in licensing a popular operating system known as CP/M (“Control Program for Microcomputers”), which was developed by Gary Kildall of the California software company Digital Research, Inc.

What happened next would cement Microsoft’s position as the world’s dominant software company for nearly two decades.

By the time Microsoft finalized the contract with IBM in November of 1980, the company’s BASIC language had many thousands of users. What Microsoft didn’t have was its own operating system product. Microsoft licensed an OS developed by Seattle Computer Products known as QDOS, which stood for “Quick and Dirty Operating System.” QDOS was similar in form and function to CP/M, making it an ideal candidate for modification—and that’s exactly what Gates did.

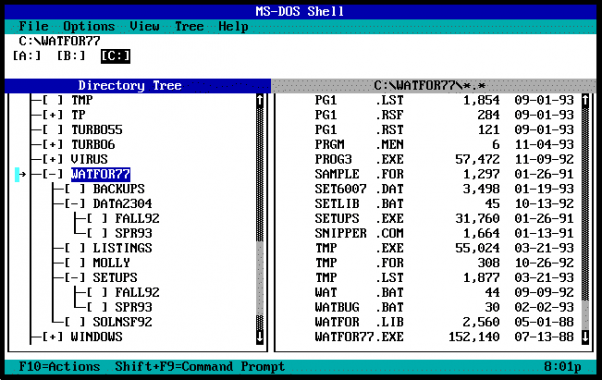

After licensing QDOS for just $10k, Gates set about rewriting core parts of QDOS’s code for Microsoft’s brand-new contract with IBM. In July of 1981, Microsoft purchased QDOS (which had been rebranded as 86-DOS) from Seattle Computer Products for $50,000. Microsoft then promptly repackaged 86-DOS for its deal with IBM, and the OS product became MS-DOS.

Microsoft’s purchase of 86-DOS is the first example of the kind of underhanded business practices Gates favored that came to plague the company in the 1990s. However, while Gates clearly had few issues with doing anything and everything possible to secure as much market share as he could—a position that largely defined Microsoft’s corporate culture in its early years—he was careful to avoid outright illegality.

When Microsoft purchased 86-DOS from SCP, the freedom for Microsoft to license the OS to other companies was a crucial condition of the sale. However, SCP later filed a lawsuit against Microsoft, claiming the company had intentionally omitted the fact that IBM was among the earliest licensees of 86-DOS. A court would later side with SCP, awarding the company $1M in damages.

“Ask Bill [Gates] why function code 6 [in QDOS and later in MS-DOS] ends in a dollar sign. No one in the world knows that but me.” — Gary Kildall, creator of QDOS

The propriety of Microsoft’s deal with IBM was far from an isolated incident of questionable corporate ethics. It actually characterized how Gates would run his company. Gates had always been competitive. Growing up, Gates and his siblings were frequently encouraged by their parents to compete with one another, which had instilled in Gates a strong desire to win—and this winner-take-all mentality would shape Microsoft’s growth trajectory.

In 1983, Microsoft’s revenues exceeded $55M. The IBM deal effectively launched the Microsoft we know today. The real genius of Microsoft’s contract with IBM, however, was that it gave Microsoft lasting control over MS-DOS, its QDOS clone. Practically overnight, Microsoft had essentially created and dominated the home computing software market. Before Microsoft, IBM dominated computer manufacturing because the large, bulky mainframes IBM specialized in were vertically integrated. IBM produced everything itself, from the chips and hardware to the operating systems and software. The arrival of Microsoft’s OS challenged this dominance by disaggregating this traditional model. This would later give rise to the company’s unofficial corporate philosophy of “a PC in every home.”

Microsoft’s early days also largely defined the company’s approach to sales. Allen had smartly anticipated the imminent explosion in the home computing market years before the PC began to make its way into homes across America. He had also predicted the rise of the consumer software market several years before it began to take shape. However, even then, Microsoft’s focus was on quantity, not quality. The software didn’t have to be good. There was virtually zero competition. More users meant more revenue. That was all that mattered.

“If you can’t make it good, at least make it look good.” — Bill Gates, former CEO, Microsoft

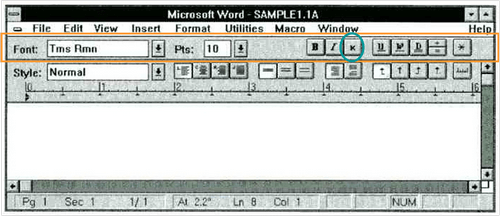

The early ’80s saw Microsoft launch several of its most popular and enduring software products. In the spring of 1983, Multi-Tool Word was released for MS-DOS and Microsoft’s Xenix operating system, a Unix clone that Microsoft licensed from AT&T in the late 1970s. Multi-Tool Word was among the very first software programs to rely primarily on mouse-based input to navigate the tool’s graphical user interface (GUI). Although the tool was aimed primarily at computing enthusiasts, many users were struck by the program’s visual interface and “what you see is what you get” interface, both of which later became design mainstays in software development.

Microsoft followed the launch of Word in 1983 with the debut of the first retail version of Windows in 1985. Unlike later versions of Windows, the first iteration of Microsoft’s flagship OS was actually a GUI for MS-DOS. Microsoft’s OS was popular by virtue of its ubiquity thanks to the IBM deal, but Windows 1.0 was a major step forward in home computing, as many computing enthusiasts were interested in moving away from command-line interfaces in favor of GUIs. However, even this launch was not without controversy. Shortly after the launch of Windows 1.0, Apple complained that Microsoft had unfairly infringed upon its own GUIs. In an ironic twist, Apple lost its suit against Microsoft before fighting its own court battle against Silicon Valley pioneer Xerox, which alleged that Apple had infringed on its GUI copyrights by developing the Lisa and Macintosh operating systems.

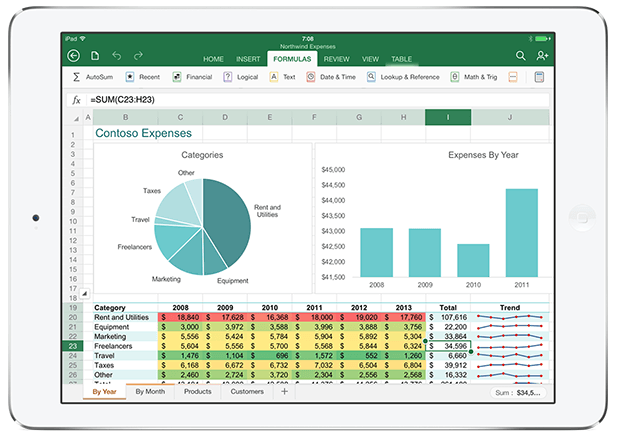

Following the launch of Windows 1.0, Microsoft released the first iteration of Excel in 1985. Ironically, the first true version of Excel Microsoft released was the Macintosh version. A Windows version of Excel wouldn’t actually be released until 1987. Excel had already been around for a few years prior to its Windows release, having been released as Multiplan for the CP/M operating system in 1982. Multiplan had been popular, but the product lost ground to Lotus 1-2-3 for MS-DOS. The launch of Excel was significant, as it would be another step toward Microsoft’s bundled Office package that would ultimately help Microsoft secure even greater market share in the rapidly growing productivity software market of the late ’80s and early ’90s.

“To catch up to Lotus, or even merely to continue to grow, Microsoft must continue to expand beyond systems software, which governs the basic functions of the computer, to the far larger market of applications programs, such as word processors and spreadsheets, which guide the computer in particular tasks.”

1985 wasn’t just an important year for product launches. It was also the year that Microsoft entered into another pivotal partnership with IBM to include MS-DOS as the default operating system of IBM’s new line of home PCs. This deal was arguably even smarter than Microsoft’s original partnership with IBM. Not only would Microsoft continue to dominate the home computing market with MS-DOS, it could also sell and license its OS to other companies. The deal was also a win for IBM, which hoped the deal would ease fears that IBM was in the process of developing and migrating to its own closed-source proprietary operating system, which would have locked out other third-party software developers and made it impossible for some existing software to run on future IBM machines.

Microsoft continued to grow throughout the late 1980s. In 1989, Microsoft released the first iteration of Office. This further cemented Microsoft’s position as the dominant business software company in North America. However, while Office was a crucial product release for Microsoft, the company had overlooked a critical aspect of the home computing market it would struggle to conquer for the next decade—the internet.

By the early ’90s, internet adoption was beginning to become more mainstream. Many consumers were going online for the first time. The price of modems, routers, and other internet hardware was falling, and the comparatively small but die-hard community of shareware developers was growing. Despite the emergence of the internet, Microsoft continued to prioritize the development of boxed software—a misstep that would almost doom the entire company.

Growth was steady throughout the early ’90s. Microsoft continued to develop its flagship Windows product, launching version 3.0 in 1990. In 1993, Microsoft released Windows NT, a version of Windows that was optimized for networked environments. Sales of NT were lackluster to begin with but picked up when it became clear that Novell’s competing NetWare operating system—sometimes nicknamed “the LAN king”—couldn’t compete with Microsoft’s dominance of the networking software market.

The next major iteration of Windows came in 1995 with the release of Windows 95. This was Microsoft’s most important product launch to date, as it was the first time that MS-DOS and Windows environments could be run on the same machine using the same GUI. Bridging DOS and Windows was a logical move given many users’ preference for GUI-based operating systems, but it was also designed to preempt Apple’s growing market share. Apple’s “Think Different” advertising campaign had emphasized the ease-of-use of Mac computers, and Windows 95 was a direct response to Apple’s growing market share. Apple posed no real threat to Microsoft’s dominance. Apple was primarily a consumer-focused company, whereas Microsoft was primarily targeting business environments. However, Microsoft couldn’t allow Apple to make any further gains into the growing consumer market.

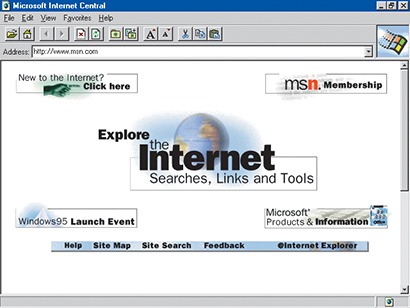

1995 was also the year that Microsoft finally began taking the internet seriously. In response to the launch of the Netscape Navigator internet browser, Microsoft unveiled its own browser, Internet Explorer. However, Microsoft wasn’t content to let the market decide who would emerge victorious in the browser wars. Upon the release of Internet Explorer 3.0 in 1996, Microsoft mimicked its earlier strategy by bundling Internet Explorer with Windows, strengthening the company’s stranglehold on the emerging browser market.

In response, Netscape accused Microsoft of engaging in monopolistic behavior—an accusation that prompted the Department of Justice to reopen an investigation into Microsoft’s business practices. In another ironic twist, one of Netscape’s founders was Marc Andreessen, who would later go on to establish venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, which would later fund GitHub—whose acquisition by Microsoft would arguably save Microsoft as a company.

By 1997, Microsoft was flying high. Revenues exceeded $11B, and return on revenue was more than 30%. Apple, on the other hand, was ailing badly. Sales were stagnant and the company stood on the brink of bankruptcy. Much of the company’s troubles stemmed from the disastrous launch of the Apple PowerBook 5300. The unit was popular with consumers, but thousands of the laptop’s lithium-ion batteries, which were manufactured by Sony, were found to be faulty and at risk of bursting into flames. To compound Apple’s woes, the PowerBook 5300 lacked a Level 2 cache, which negatively impacted system performance. Apple’s share value tanked, and on July 9, 1997, Gil Amelio was ousted as CEO by the company’s board, a shake-up that heralded the return of prodigal son Steve Jobs as chief executive.

“Apple was in very serious trouble. And what was really clear was that if the game was a zero-sum game where for Apple to win, Microsoft had to lose, then Apple was going to lose.” — Steve Jobs, founder and former CEO, Apple

In a move that shocked the tech world, Jobs announced that Microsoft had committed to making an investment of $150M in Apple at the Macworld Expo Boston in 1997. Speaking over the boos of the packed crowd, Jobs told the audience that Microsoft would be developing a series of applications for the Mac OS, including a native version of Office.

According to Silicon Valley legend, Microsoft “saved” Apple with its investment during Apple’s darkest hour. The truth, however, is far more mundane. Microsoft didn’t care about developing apps for the Mac—at least, not then. Microsoft needed to score some good PR and bailing out its most bitter enemy was an excellent way to accomplish that. Gates’ respect for Jobs was genuine, but Gates recognized Jobs for what he was—a competitor who needed to be controlled, then crushed.

What many people either forget or don’t know is that Microsoft’s investment in Apple was a direct result of Microsoft’s legal troubles over Apple’s QuickTime video codec. Apple had sued software developer San Francisco Canyon Company in 1992 for allegedly using portions of Apple’s proprietary QuickTime code for its QuickTime for Windows application. Microsoft’s $150M investment in Apple wasn’t a gesture of goodwill among former enemies or an olive branch for an innovative yet struggling company—it was part of a settlement package Microsoft had been ordered by a court to make. Gates didn’t care about saving Apple. He just needed to make an inconvenient lawsuit disappear and figured he could earn Microsoft some much-needed positive PR into the bargain. As cynical as this may have been, it was an undeniably brilliant move by Gates and one whose truth has been largely consumed by Silicon Valley folklore.

Gates’ relentless ambition to secure market share for his growing company at any cost had made Gates and Allen multimillionaires in just six years. It also made the company vulnerable. As Microsoft’s frequent courtroom battles had revealed, the company was ready to do whatever it took to dominate the growing personal computing market—and that readiness to crush any and all competitors would very nearly doom the entire company.

2000-2010: Rebuilding Trust and the Ballmer Era

By the early 2000s, Microsoft had been severely bruised by its numerous legal battles. Despite this, annual revenues exceeded $22B. Microsoft would spend the next several years attempting to restore its public image. However, this period would be far from easy for the beleaguered company. Gates’ departure as CEO, and the appointment of Steve Ballmer as his replacement, marked the beginning of a baptism of fire for Microsoft that saw the once-mighty company struggle with botched product launches and a fundamental shift in its identity and direction. Microsoft had been extraordinarily successful at building a platform. Unfortunately for Microsoft, its confidence in the security of that platform blinded the company to the fact that its hubris would jeopardize everything Microsoft had built thus far.

When Gates transitioned from CEO to Chief Software Architect—a position Gates created for himself—in 2000, it marked the beginning of a whole new era of problems for Microsoft. Gates’ replacement, his long-time friend and Harvard classmate Steve Ballmer, had been with Microsoft in one capacity or another since 1980 and had been President of Microsoft since 1998.

When Ballmer took the reins, Microsoft’s valuation was a stunning $558B. The company had finally embraced the potential promised by the internet, and sales of Windows remained comparatively strong. However, the company could no longer rely solely on its formerly successful boxed software approach. The internet was becoming an increasingly popular means of distributing software, and despite Microsoft’s uncontested dominance of the consumer software market, the company needed to explore new potential revenue streams.

In 2001, Microsoft got into the video games business with the release of the first-generation Xbox gaming console. The following year, the company launched its online gaming network, Xbox Live. Microsoft’s first foray into the gaming vertical was hardly surprising. Even in 2000, the video game market was worth more than $8B.

What was remarkable about the Xbox was that it was a surprisingly successful hardware product launch for a company that was much more comfortable selling boxed software at volume than trying new things. Even more remarkable was the fact that Microsoft was able to enter a crowded, savagely competitive retail market with a brand-new product. For once, Microsoft’s timing was spot-on. More importantly, Microsoft had successfully leveraged a high-profile hardware product launch to break into a brand-new vertical for the company.

Some companies live and die by the success or failure of a single product. For companies like Microsoft, not every product can be a runaway success. The utility and ubiquity of Microsoft’s productivity tools, particularly in the workplace, is indisputable. However, Microsoft has never been particularly good at developing consumer products that people actually want. This didn’t harm the company in its early days, as most early PC adopters were locked into using Microsoft’s software by design. It didn’t hurt Microsoft’s business software divisions either, because most companies had built their workflows around Microsoft’s business productivity tools. The company’s inability to truly understand the consumer market became a huge liability for Microsoft as competitors began to emerge that offered products that were fundamentally better than Microsoft’s products. Microsoft simply didn’t know how to compete when it came to raw product.

From 2006, Microsoft was beset by a series of high-profile product failures that did enormous damage to Microsoft’s already bruised reputation. The first such launch was Microsoft’s immensely unpopular Zune MP3 player. This was followed by the release of Windows Vista, which boasted a rich, sophisticated GUI but was deeply unpopular with even the most die-hard Microsoft loyalists.

In many ways, Microsoft’s most interesting products have been the company’s most abject failures. The Zune was largely seen as a cash grab and an attempt to once again co-opt the genuine innovation of Apple’s immensely popular iPod. This is also another example of how Microsoft’s “quantity versus quality” approach to product ultimately harmed Microsoft as a brand. Microsoft didn’t care whether the Zune was the better MP3 player, only that it could sell more than Apple.

This demonstrates how Microsoft’s early culture of dominating by sheer force of numbers, as opposed to creating genuinely superior products, continued to shape the company’s approach to product development even as Microsoft attempted to break into new, highly competitive verticals. For one, Microsoft’s timing was once again absolutely terrible. By the time the Zune was released, Apple had a five-year head start with its iPod. Apple effectively owned the nascent MP3 market before Microsoft even got out of the gate. The second major flaw with the Zune was that it just wasn’t necessary. There was nothing “wrong” with the Zune per se. It just couldn’t offer users anything that Apple’s iPod didn’t already offer. There was literally no reason for a consumer to choose a Zune over an iPod other than blind brand loyalty. Microsoft didn’t even try to go after Apple on pricing, opting to introduce the Zune at an SRP of $249.99, compared to the $229 Apple was charging for its fourth-generation iPod.

“I think our marketing message was very confused. I don’t think people walked away saying, this is what Zune is and this is why it’s different. This is why I have to have it. We did some really artsy ads that appealed to a very small segment of the music space, and we didn’t captivate the broad segment of music listeners.” — Robbie Bach, former President, Entertainment & Devices Division, Microsoft

This principle also applied to Windows Vista. Many people appreciated Vista’s “glass” GUI but found the OS itself to be severely lacking. However, Microsoft’s real failure with Vista wasn’t necessarily a problem with Vista itself, but that it failed to improve on Windows XP. Simply put, Windows XP had been such an improvement over Windows 2000, Microsoft had inadvertently set itself up to fail by regressing on everything that users loved about XP. The only tangible improvement Vista had over XP was its security functions, which were seen as a major improvement.

For the first time ever, Microsoft had built such a good product, it actually hurt itself trying—and failing—to improve upon it.

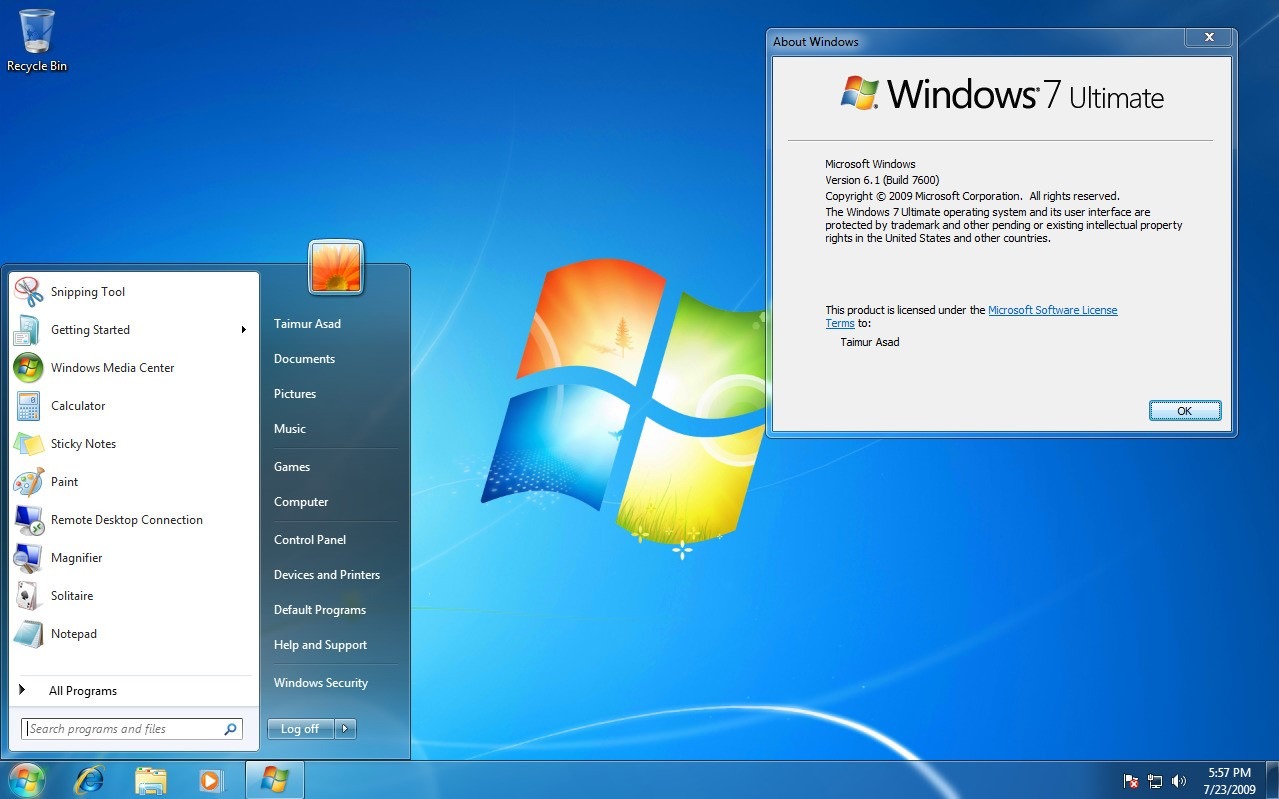

Hot on the heels of the disaster that was Vista, Microsoft doubled down on Windows with the release of Windows 7. Seen as a huge improvement, Windows 7 should have been a step in the right direction for Microsoft after the catastrophe that was Windows Vista. Windows 7 directly addressed many of the most-hated features of Windows Vista, such as streamlining how user account controls were handled by system administrators and the hardware compatibility issues that plagued lower-end machines that struggled to run Windows Vista smoothly.

However, even the launch of Windows 7 wasn’t without issues. Rather than releasing its new OS as a single version, Microsoft released no fewer than six different versions of Windows 7: Starter, Home Basic, Home Premium, Professional, Enterprise, and Ultimate. Not only did this confuse consumers, who were given little guidance on what features came with each version or which version was right for them, but also demonstrated how Microsoft struggled to understand the fundamentals of the consumer market. Microsoft had always known its buyer intimately. The problem was that Microsoft’s ideal buyer has always been the manager, not the user. With Windows 7, Microsoft had effectively packaged a consumer product for the business market in the way it always had.

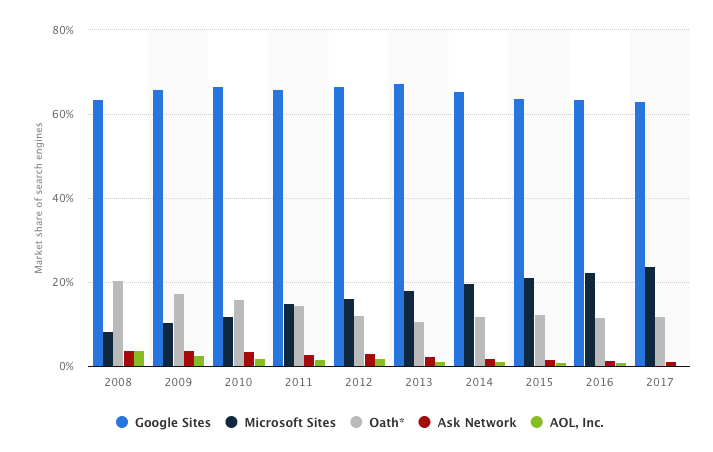

In 2009, Microsoft once again demonstrated its unique talent for being late to the party when it launched its Bing search engine. Bing itself wasn’t terribly effective, particularly compared to Google’s growing omniscience, but the launch itself wasn’t much better. Once again, Microsoft was five years behind the market-leading competitor. However, by Microsoft’s own admission, Bing wasn’t supposed to be a “Google killer” as many in the tech press mistakenly believed. Microsoft knew there was no way Bing could compete with Google, particularly with more than five years of R&D between the two products. Microsoft could, however, start chipping away at Google’s market share—and the enormous advertising revenues that came with it. When Bing launched in 2009, Google controlled more than 64% of the U.S. search market and earned approximately $22B in ad revenues from Google AdWords. If Microsoft could attract even 5% of Google’s users, that could translate to more than $1.1B in potential ad revenue—not bad for an objectively inferior product.

The final catastrophic product launch of the 2000s was arguably one of the company’s biggest failures to date, the Windows Phone. The devices that ran Microsoft’s mobile OS weren’t the problem. Perhaps surprisingly, many Windows Phone devices ran and felt a lot smoother than Android devices. Several prominent Windows Phone devices were lauded for their innovative design features, such as the Samsung Omnia 7, which boasted a revolutionary 4-inch OLED display, and the immensely popular Nokia N9. Windows Phone’s biggest obstacle was Google, whose Android platform had risen to dominate the mobile device market around the world.

Microsoft’s Windows Phone was beset by a range of predictable yet serious setbacks, not least of which was Google’s refusal to develop apps for the device. Google’s effective stranglehold on its immensely valuable third-party app developer marketplace was just too strong. Availability of popular apps such as Instagram and Snapchat was hit or miss, but Google’s refusal to develop a native YouTube app for Windows Phones in 2013 would ultimately spell doom for Microsoft’s mobile OS.

“We’ve got a big challenge in front of us. We’re a very small player, but we have a different point of view in terms of user experience. We’ve got great cloud integration with the rest of the Microsoft world, which a lot of people participate in. So I think our point of view on user interface, the great work that our hardware vendors are doing and the integration with Windows should help ratchet us up.” — Steve Ballmer, former CEO, Microsoft

Despite its efforts to regain the trust of consumers worldwide, Microsoft struggled to move beyond the reputation it gained during the antitrust lawsuit that cast such a vast shadow over the company in the ’90s. Microsoft had faltered badly during the 2000s, and its difficulties were compounded by a series of high-profile product failures. However, for all its troubles during the 2000s, Microsoft ended the decade on a high note, having secured between 86-92% of the world’s operating system market. What the company needed now were fresh eyes and a new start—but the company would have to endure several more high-profile missteps before Microsoft was finally forced to acknowledge the repeated failures of its leadership.

2011-Present: From Walled Gardens to Open Source

By 2011, Microsoft had well and truly lost its way. After struggling to realign its business with changing shifts in software distribution, Microsoft had failed to regain much of the momentum it had established during its heyday more than 20 years previously. The company’s numerous product missteps in the 2000s had done little besides confuse consumers and cast doubt on Steve Ballmer’s leadership. To complicate matters, the company was facing bitter competition from not one but several of Silicon Valley’s largest and wealthiest tech companies. Microsoft needed to strongly reassert its position at the top of the food chain.

After enduring several failed product launches, Microsoft realized that Google had made tremendous gains in the productivity software market. To add insult to injury, it had done so by making its suite of tools available to users completely free—a slap in the face for a company that had made its vast wealth by selling boxed software. To invigorate its ailing productivity division and attempt to halt Google’s seemingly unstoppable rise, Microsoft debuted Office 365 in 2011.

Although Office 365 would ultimately prove to be one of the most popular Microsoft products in recent memory, it was also a predictable move. Microsoft had made little secret of its intentions to move more services to the cloud, and its corporate workhorse was an obvious candidate. However, it was also seen as yet another reflexive, defensive play by a company that had been backed into a corner by the aggressive plays of Google and emerging productivity startups across Silicon Valley.

Shortly after the launch of Office 365, Microsoft announced it was acquiring VoIP telecom service Skype for $8.5B—Microsoft’s largest acquisition to date. At the time, Microsoft’s acquisition of Skype raised more than a few eyebrows. For one, Microsoft’s existing VoIP and messaging platforms, Live Messenger and the corporate-focused Lync 2010, had roughly three times as many users as Skype’s comparatively meager 124M users worldwide.

Another element of the sale that had analysts scratching their heads was Skype’s own struggles to reach profitability. At the time, Skype had achieved a relatively sluggish $840M in profit. Given the terms of the deal, Microsoft was effectively paying more than $1,000 to acquire each of Skype’s paying subscribers, vastly more than each individual customer represented in terms of profit. Skype certainly aligned closely with Microsoft’s existing product portfolio, but Microsoft arguably could have built its own VoIP infrastructure from scratch for less than it paid for Skype.

The real reason Microsoft bought a struggling VoIP platform for more than $8B was simply so Google and Facebook couldn’t. At the time, there was much speculation about a potential deal between Google, Facebook, and Skype. Nobody was willing to talk on the record about what such a partnership might entail, but heading off already intense competition by buying out Skype before anyone else is almost certainly why Microsoft paid considerably more for Skype than the company was worth.

Microsoft may have shifted its focus to cloud-based services and online software, but the company hadn’t given up its ambitions of securing another major win for a hardware product. In 2012, Steve Ballmer unveiled the first of its Surface range of devices at an event at Los Angeles’ Milk Studios. The Surface range was unique in that, in a radical departure from Microsoft’s historical modus operandi, the company had designed the Surface in-house. It would be the first range of devices designed by Microsoft specifically for Windows software.

The Surface was immediately and wildly popular.

The initial Surface line came in just two versions: a thinner, lighter, consumer-focused model optimized for Windows RT, and a thicker, heavier model aimed at business users. For all its innovation, the Surface was a quintessentially Microsoft product. Despite observing seismic shifts in hardware specifications and software distribution firsthand, Microsoft under Ballmer’s leadership was still slavishly devoted to the relationship between hardware and software. Twenty years previously, Microsoft had sought to dominate the consumer PC market by entering into exclusive distribution partnerships with key manufacturers like IBM. Now, Microsoft was trying to do exactly the same thing all over again. The only difference was that Microsoft was now designing its own hardware.

Riding high on the success of the Surface launch, Microsoft could have leveraged the resurgence in its popularity to reinvent itself and finally shake its reputation as an out-of-touch company with few ideas.

Unfortunately for Microsoft, it released Windows 8 instead.

The launch of Windows 8 served as a painful reminder that Microsoft really hadn’t learned anything from Windows’ previous troubled iterations. That’s not to say that Windows 8 wasn’t a major step forward for Microsoft’s flagship OS. Its tiled interface optimized for Microsoft’s Surface range of devices blended the core functionality of a desktop operating system with the native touch-screen optimization of a tablet, making it one of the first truly blended OS environments ever released. Windows 8 also brought with it several urgently needed overhauls to long-time Windows features, including a reworked Task Manager, updated file history functionality, and improvements to Windows’ storage management capabilities.

However, for every step forward, Windows 8 took two steps back. The OS itself was highly customizable, but Windows 8 offered very little in the way of guided flows or even basic tutorials on how users could get the most out of their new operating system. Many users were put off by how Windows 8 looked and felt different across multiple devices or even when switching from tablet to desktop mode on certain Surface devices. In one particularly biting review, one tech journalist described Windows 8 as “a Frankenstein’s monster of cobbled together parts that are clumsy and impractical.”

“Windows 8 wasn’t born out of a need or demand; it was born out of a desire on Microsoft’s part to exert its will on the PC industry and decide to shape it in a direction—touch and tablets—that allows it to compete against, and remain relevant in the face of Apple’s iPad.” — Adrian Kingsley-Hughes, ZDNet

Microsoft dropped the ball again in 2012 when it acquired Slack clone Yammer for $1.2B. At face value, the Yammer deal made sense. Microsoft had long been an enterprise heavyweight, and Yammer’s goal of socializing the world of work certainly aligned with Microsoft’s apparent desire to somehow monetize workplace chat. However, the Yammer acquisition was a very risky play for Microsoft. When Microsoft acquired Yammer, the fledgling social enterprise company had roughly 4M users, but only 20% of those users were paid subscribers. This meant Yammer wasn’t an immediately viable revenue stream for Microsoft without further significant development.

Ballmer’s vision for Yammer was conflicted at best. He wanted to apply the freemium model to drive user adoption of Yammer. However, Ballmer also wanted to drive conversions across two dimensions. Not only did he want to bridge the gap between free users and paid subscribers, he wanted to entice consumers to try Yammer for free before pushing for paid subscriptions to Yammer in the workplace. As the growth of Slack would prove, converting users from free to paid was hard enough. Attempting to drive conversions from personal free accounts to paid workplace subscriptions was suicide.

“As long as we continue to drive hard with Yammer as a consumer offering, and then we ramp up the Microsoft sales force to help rapidly accelerate the degree to which we get corporate conversions, I think we’ll see a very, very nice revenue ramp fairly quickly.” — Steve Ballmer, former CEO, Microsoft

Later that year, the company unveiled a new logo. It was the first major rebrand Microsoft had undergone in 25 years. The company’s fresh, minimal branding was a badly needed breath of fresh air at the company, but the bigger shakeup would come two years later in 2014, when Microsoft appointed Satya Nadella as the company’s new CEO.

Nadella’s appointment as CEO arguably saved Microsoft as a company. Microsoft had somehow survived Ballmer’s catastrophic tenure and badly needed a new leader who could help the company find its new identity. Microsoft wasn’t just struggling as a company by the time Ballmer eventually departed—many of the company’s employees were, too. Morale had hit rock bottom across many of the company’s most important divisions. Long-time employees and new hires alike were burned out by seeing their hard work flame out in poorly planned product launches. Even key senior personnel, including former Chief Software Architect, Ray Ozzie, had left the company disillusioned.

“The company was sick. Employees were tired. They were frustrated. They were fed up with losing and falling behind despite their grand plans and great ideas. They came to Microsoft with big dreams, but it felt like all they really did was deal with upper management, execute taxing processes, and bicker in meetings.” — Satya Nadella, CEO, Microsoft

Nadella, who had worked in various roles across Microsoft since 1992, had two primary challenges. First, he had to turn around the company’s troubled financial prospects and show investors that Microsoft was still the world’s preeminent technology company. Secondly, he had to transform Microsoft’s stuffy, corporate culture to attract new technical talent and boost morale.

In early media appearances as the company’s newly minted chief executive, Nadella reiterated what everybody already knew—that Microsoft’s future was mobile-first, cloud-first. However, very few observers predicted what came next. In a fundamental shift in Microsoft’s entire ethos as an organization, Nadella announced in 2013 that Microsoft was developing an iOS-native version of Office for Apple’s iPad. Compared to Microsoft’s bitterly resistant, walled-garden approach to software development, this announcement was unprecedented.

The first major product launch under Nadella’s leadership was Windows 10, which was released on July 29, 2015. In true Microsoft fashion, the launch was a disaster. Windows 10 looked great and featured Microsoft’s Cortana virtual assistant as well as the company’s Edge browser. However, under Windows 10’s sleek exterior lay the same problems Microsoft had failed to learn from in earlier iterations of its flagship OS.

The launch itself was heavily criticized. Microsoft’s forced upgrade to Windows 10 from earlier versions meant many users felt they had little choice but to upgrade to Windows 10, even if they were happy with their existing version. Many users were particularly unhappy with Windows 10’s built-in advertising, claiming that Microsoft was forcing ads on users by recommending “suggested” apps from Windows 10’s home screen and Start Menu. Windows 10 also frequently prompted users to upgrade to paid subscriptions of Office and other software tools.

Put another way, Windows 10 was an advertising platform that worked like an operating system.

Between the launch of Windows 10 in 2015 and 2018, Microsoft largely flew under the tech industry’s collective radar. There were no major product launches during this period, and although the company continued to invest in artificial intelligence and machine-learning technologies, there were few major product developments. However, Nadella’s influence on Microsoft’s culture could be seen—and felt—across the entire company.

Similarly to Microsoft’s newfound friendship with Apple in 2013, Microsoft began cultivating relationships with several of the company’s former competitors. This included a pivotal collaboration between Microsoft Azure and IBM in 2014, a landmark integration with Salesforce in 2015, and a very smart, strategic integration between Office 365 and Dropbox in 2016. Nadella wasn’t just transforming Microsoft’s culture from within. He was also challenging perceptions of Microsoft as a company and building vital bridges between his company and many of its former enemies. Microsoft even became a Platinum member of the Linux Foundation in 2016, a highly symbolic gesture that served as a reminder of just how profound Nadella’s influence as CEO had been in just a few short years.

In June 2018, Microsoft announced it was purchasing code-sharing service GitHub for $7.5B in stock.

The deal sent the tech press into a frenzy. What would Microsoft do with the largest code repository in the world? How would it leverage GitHub’s immense community of programmers? Why now? The answer to all these questions was that, to Microsoft, buying GitHub made perfect sense. GitHub had built an incredibly successful business by tackling a huge problem universal to software developers—how to effectively collaborate on code. GitHub was the largest open-source code repository in the world, but it wasn’t the amount of code stored on GitHub that Microsoft found attractive. It was the vast, ready-made community of loyal GitHub users that Microsoft really wanted.

Microsoft may have felt pretty good about its shiny new toy. GitHub users, on the other hand, weren’t so thrilled. As news of the acquisition spread online, many GitHub users vowed to migrate their codebases to other services such as Bitbucket and GitLab. However, what many of these users failed to realize was that Microsoft’s acquisition of GitHub would have virtually no meaningful impact on GitHub as a product or service. GitHub has dominated the collaborative coding space for more than a decade. It’s hard to imagine—but not impossible, of course—to imagine what Microsoft could do to jeopardize GitHub’s uniquely enviable position in the wider software development ecosystem.

June 2018 was a busy month for Microsoft beyond its surprise acquisition of GitHub. In addition to making its largest acquisition to date, Microsoft spent that June launching a brand-new, redesigned version of Office, announcing its forthcoming “cashier-less” retail technology, and rounded out the month by acquiring artificial intelligence startup Bonsai for an undisclosed sum.

All three of these moves were highly strategic and revealed a glimpse of Nadella’s longer-term growth strategies. The update and refresh of Office had been long overdue and ensured Microsoft’s productivity suite matched competing tools in both appearance and functionality. Microsoft’s cashierless technology isn’t just an example of Microsoft’s hardware division meeting changing needs in consumer shopping preferences—it also puts pressure on Amazon, which has its own plans to expand its autonomous cashier systems. The acquisition of Bonsai was the most transparent of Microsoft’s moves. Microsoft may have taken far too long to get into the AI R&D game, but purchasing Bonsai was a smart step forward for a company that now apparently recognizes the speed and urgency with which AI and machine-learning technologies are transforming computing.

Very few companies can afford to make as many missteps as Microsoft has. Despite this, for all its faults, it’s impossible to imagine modern computing without the company that Gates and Allen founded in 1975. Under new management, Microsoft’s future is perhaps brighter now than it has ever been—but the company must tread carefully if it hopes to remain not just competitive, but relevant, in today’s rapidly changing technological landscape.

Where Could Microsoft Go from Here?

Microsoft’s reputation for its reluctance to embrace change is well-deserved, but the company appears to be moving forward with a renewed sense of purpose under Nadella’s watchful eye. Where could Microsoft go from here?

1. Greater integration between GitHub and Azure

Microsoft has finally realized that the cloud is where the battle for dominance will be fought. As such, it’s inevitable that Microsoft will leverage its acquisition of GitHub to attack Amazon Web Services and Google Cloud services aggressively.

2. Renewed emphasis on voice search

Microsoft has never had much luck with its search business, but the company is playing the long game with emerging technologies such as voice search. We’re likely to see continued investment in voice from Microsoft from a technical perspective (i.e., further improvement/development of Cortana) as well as further potential acquisitions of emerging companies in the voice space.

3. Vigorous defense of its enterprise business

Microsoft’s software might be unpopular with most consumers, but the company maintains an iron grip on the enterprise thanks to the dominance of Office. Although Microsoft is likely to broaden its horizons in the coming years, it will have to work hard to maintain its stranglehold on the enterprise particularly in light of aggressive competition from startups like Box.

3 Lessons We Can Learn from Microsoft

The world is a very different place than it was when Gates and Allen founded Microsoft in 1975, but there are still plenty of valuable lessons to be learned from Microsoft’s journey.

1. Market share equals longevity

Microsoft never wanted to be the best software company—only the biggest. The company’s relentless pursuit of market share gave the company the clout and resources it needed to weather the various storms of the ’90s and 2000s. Without that early market dominance, the company may not have survived so many mistakes.

Think about your product and its place in your industry, then answer the following questions:

- How are you building—and protecting—your market share? Are you the only real player in your space? If not, how are you differentiating your product?

- Microsoft cleverly leveraged its early partnerships with IBM to not only create a strong foothold in an emerging market, but to allow it to license its software to other companies. This move was pivotal to the company’s early growth. How can you forge similar relationships with other companies in your space?

- Is your product development strategy focused on long-term growth or short-term gains? Put another way, are you missing out on bigger growth opportunities in favor of securing smaller wins?

2. Know your buyer

Despite their broad adoption and impressive market penetration, Microsoft’s products have never been particularly popular with consumers. The company has, however, always known its ideal buyer intimately—managers, not end users. This knowledge is essential, especially for companies operating in highly competitive markets.

Look over your user data and growth projections, then think about the following:

- If you’re primarily a B2B company, are you marketing your product to individual end users, or are you targeting buyers? What’s the rationale behind how you’re targeting prospective users and could it be improved?

- Be honest—would you increase adoption if your product were better? If so, why haven’t you invested in these improvements? What’s the single biggest step you could take toward improving your product and adoption?

- Do your users genuinely love your product, or do they just need it? Put another way, are you relying on the exclusivity of your product or service to grow, or are you cultivating loyal brand ambassadors by focusing on your product’s potential?

3. Adapting to fundamental shifts in a market is very difficult

It can be very hard for even young companies to change and adapt to fundamental shifts in a market. Microsoft’s slavish devotion to the boxed-software model almost killed the company. Successfully shifting focus in a changing market requires a keen understanding of not only your core strengths but your most vulnerable weaknesses.

Microsoft effectively created—then dominated—a brand-new market by cleverly anticipating bigger shifts in the nascent home computing market. What Microsoft failed to do, however, was respond in a timely way to clearly evident changes in how people bought and used software and adapt accordingly.

Consider where your product “lives” in your industry, then answer the following questions:

- What’s the single greatest threat to the stability and future growth of your product and/or company, and how are you preparing to mitigate this threat?

- Think about your company, your product, and your business model. If you had to pivot or adjust your growth strategy to compensate for emerging threats to your current model, what would this look like? Would it be a relatively easy transition, or—like Microsoft—would you have to fundamentally reshape your company and its culture to survive this transition?

- Microsoft’s size, revenue, and market penetration were all seen as positives—until the company had to rethink its entire philosophy and mission to respond to a rapidly changing market. What “strengths” does your company possess that could actually be liabilities if you had to change direction?

Windows to the World

Microsoft may not have the kind of reputation that newer companies like Google and Facebook enjoy. It does, however, occupy a truly unique place in the history of computing technology. Without Microsoft, the world would look, feel, and work a lot differently than it does today—and Bill Gates’ relentless drive to succeed was a driving force behind his company’s incredible growth and longevity.

Under Satya Nadella’s watchful leadership, Microsoft emerged from one of its most challenging periods to finally become the 21st-century technology company it has always promised to be. The company’s future is far from guaranteed, however, and Nadella will have to continue challenging his company to do better and be better if his company is to succeed.

At Satya Nadella’s Microsoft, it seems that quality may finally be more important than quantity.