How an Anti-Growth Mentality Helped Basecamp Grow to Over 2 Million Customers

“How much is Basecamp worth? I don’t know, and I don’t care.” – Basecamp Founder & CEO, Jason Fried

There’s a common roadmap for SaaS growth.

Build a product that solves a need for your core audience. Raise venture dollars to build new products and features. Land and expand upmarket to the enterprise.

Basecamp has built one of the oldest and longest-surviving businesses on the Internet by flipping this conventional wisdom on its head.

Basecamp, the web-design-turned-software company, has done this by sticking to a specific ethos: simplicity in software. They built and refined a single, simple project management tool to help people do their jobs better. Eighteen years later, that simple project management tool has helped them grow to $25 million in ARR. This is even more remarkable because their focus has never been on revenue or growth.

Basecamp was founded in 1999, the same year as Salesforce and Google (among many other tech companies). While companies like Salesforce and Google survived by building out a ton of tools to keep acquiring new types of customers, the Basecamp you see today hasn’t changed that much over 18 years. They threw all of their weight behind their original ideas—and that’s how they’ve sustained the company ever since.

Let’s take a closer look at how Basecamp has succeeded without focusing on growth for growth’s sake. Specifically, we’ll talk about:

- How and why Basecamp pivoted from a web design consultancy to a product company—but maintained a consultancy mentality

- How Basecamp built an experimental suite of software products, only to refocus back on one

- How Basecamp actively avoids pressure to complicate their product, accept VC money, or prioritize revenue over profit.

We’ll look at how Basecamp has shaped their product, company, and ethos around an anti-growth mentality.

1999-2004: From Web Design Company to Project Management Software

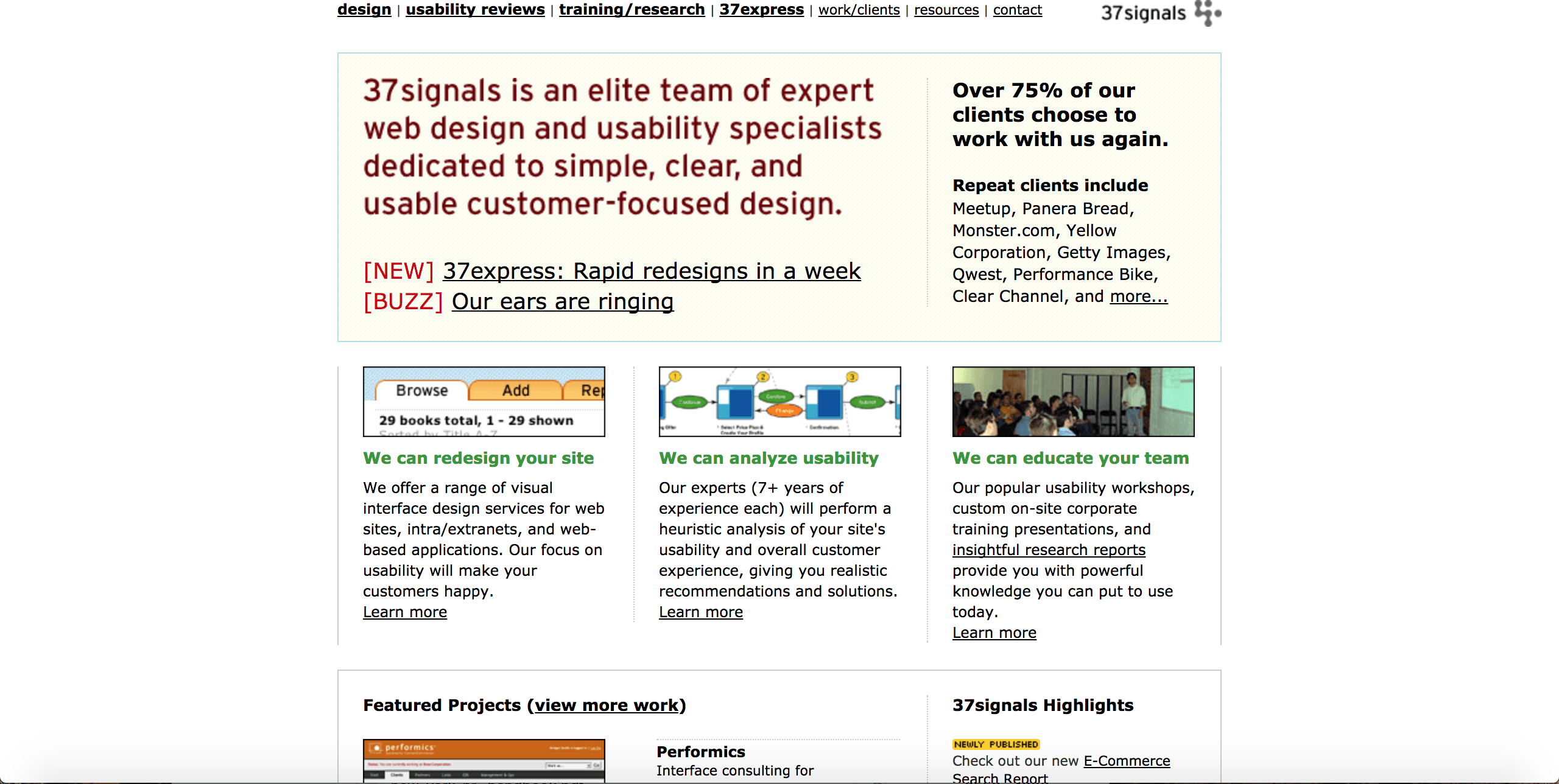

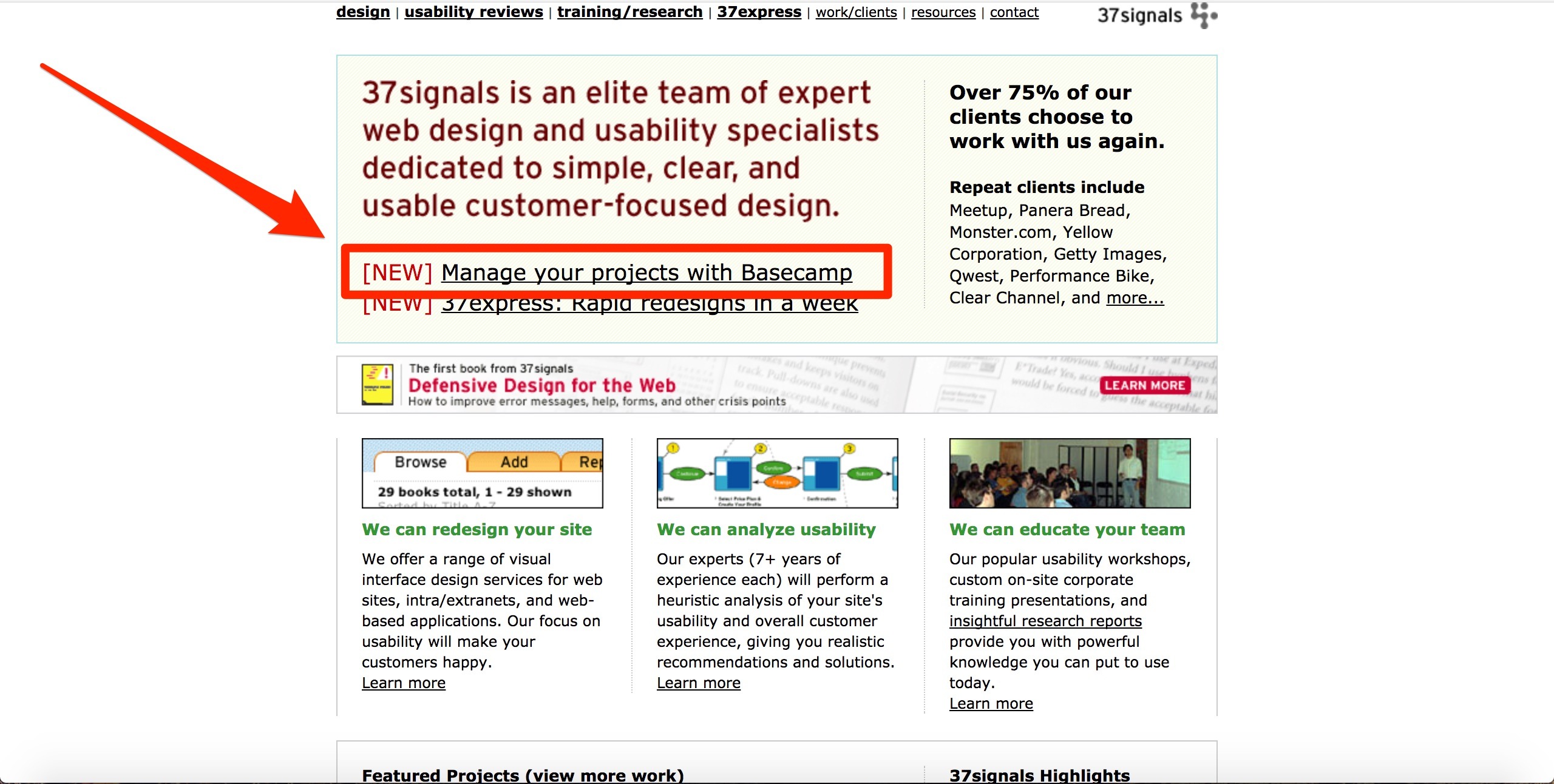

Basecamp started as a single project management tool for Jason Fried’s web design consultancy called 37signals. It wasn’t originally supposed to be a “product”—rather, it was an in-house tool that the team scrapped together because they needed a better way to handle their own work.

The tool was supposed to be simpler and easier to use than any other project management tool that Fried had tried. It needed to match his own philosophy on software development: “Keep it simple.” Truly sticking to this philosophy in their product and their company development cemented Basecamp’s early success.

Most startups aim for quick, early growth at any cost. Eventually, they can’t keep up this pace and their growth slows. Their trajectory ends up looking something like this:

From the very beginning, Basecamp railed against growth for growth’s sake. They focused on giving customers what would help them and making sure that the company was making money. Their growth looked more like this:

Out of the gate, they prioritized steady growth—not fast growth. The team made sure that they never grew faster than what they could reasonably accomplish and profit from. They believed throughout their entire trajectory that profit was one of the best indicators of a company’s success:

“If a restaurant served more food than everybody else but lost money on every diner, would it be successful? No. But on the Internet, for some reason, if you have more users than everyone else, you’re successful. No, you’re not.” – Jason Fried

Instead of trying to “sell more food than all of the other restaurants,” the team thought small and simple. And while other companies strive for simplicity and ease of use, no other company has executed on that mission the way Basecamp has. Here’s an early year-by-year look at how Basecamp was born:

1999: Jason Fried, a recent college grad, founded a web design consultancy that he called 37signals. He was first and foremost interested in UX design, and had built a few of his own streamlined software products before starting his consultancy. By the time he founded 37signals, Fried had published 37 tenets of “internet wisdom” about simplicity in software. Here are some of my favorites:

- “The web should empower, not frustrate.”

- “One should not increase, beyond what is necessary, the number of entities required to explain anything. [Occam’s Razor]”

- “We think companies that claim they can do everything actually excel at nothing. That’s why we choose to do one thing and do it right.”

- “The truth is corporations don’t use websites, people do. B2whatever, we’ll design a site that works for the person on the other end.”

2002: These ideas formed Fried’s ethos for building software—and they were very sticky. By writing on his blog, Signal vs. Noise, Fried attracted a community of people who liked his ideas about simple software design. One of these was a Danish student at Copenhagen Business School named David Heinemeier Hansson. The two started talking regularly about their ideas regarding programming and web design, and realized their outlook was exactly the same: “Keep it simple.”

2003: 37signals was getting a lot of clients. Fried needed some sort of software tool to manage these different projects, but he wanted a bare-bones tool that matched his website’s interface. To build the tool he wanted, he turned to the programmer whose ideas completely matched his—Hansson. In four months, Hansson scrapped together a bare-bones project management tool.

2004: Clients started asking about Fried’s project management tool. That’s when Hansson and Fried realized that the tool had commercial potential and would bring simple software to other small teams in their day-to-day work. They released Basecamp as a simple collaboration tool for small teams. People could sign up for a subscription plan right on the 37signals website.

At this point, 37signals was making money both from Basecamp subscriptions and from web design products. They were still a consultancy, and this mentality showed in Basecamp—it was a simple point solution for a problem that Fried himself was trying to solve.

The first set of subscription plans for Basecamp ranged between $12-$149. These prices were perfect for small teams that would find the basic interface useful.

At the same time, one of the most interesting aspects of their pricing plan was that they decided from Day 1 to charge flat rates rather than to charge by seat. As Fried said, this allowed them to focus on delivering the best product possible to all of their customers, instead of focusing on chasing large contracts. The company put the emphasis on the “Fortune 5,000,000,” not the Fortune 500.

The easy-to-use product and easy-to-stomach pricing made Basecamp spread like wildfire. In just six weeks after release, they hit their 1-year goal of $5k MRR.

In a way, releasing Basecamp as a commercial product was the start of Fried and Hansson’s rage against everything that other tech startups held dear. But at the same time, it was just a continuation of the ideas that both Fried and Hansson already had brewing for many years. In an interview, Fried said that his philosophy was: Build what we like, and other people will like it, too.

It was never about selling the product. It was about helping people in the style that the co-founders thought was best. And after the success of Basecamp, Fried and Hansson began to try to find other ways to help people with simple software.

2005-2013: Building—and pruning—a suite of apps

Fried and Hansson started exploring how simple software could help small businesses by creating new, highly specific products for different tasks. A lot of users loved these new simple tools just as much as they loved Basecamp. That made it all the more unusual when 37signals cut all of these new, money-making products and returned to being a one-product company a decade in.

In the early days, Basecamp experimented by building a bunch of smaller projects and apps outside of the core project management product. There weren’t many other SaaS tools out there, so they could test out new ideas and actually see how helpful these simple software tools were for people.

As other companies started building their own SaaS tools, there was pressure to maintain and add to all of their tools to out-do competitors. Other companies in similar positions try to own all of these different verticals by creating a lot of different tools that are all the best at everything they do.

Basecamp took the complete opposite approach and cut out everything they didn’t want to focus on. They doubled down on their original project management tool, and focused all of their attention on improving the basics. Then they were able to take all of the things they’d learned from their other products and apply the best ideas back to their original product, Basecamp.

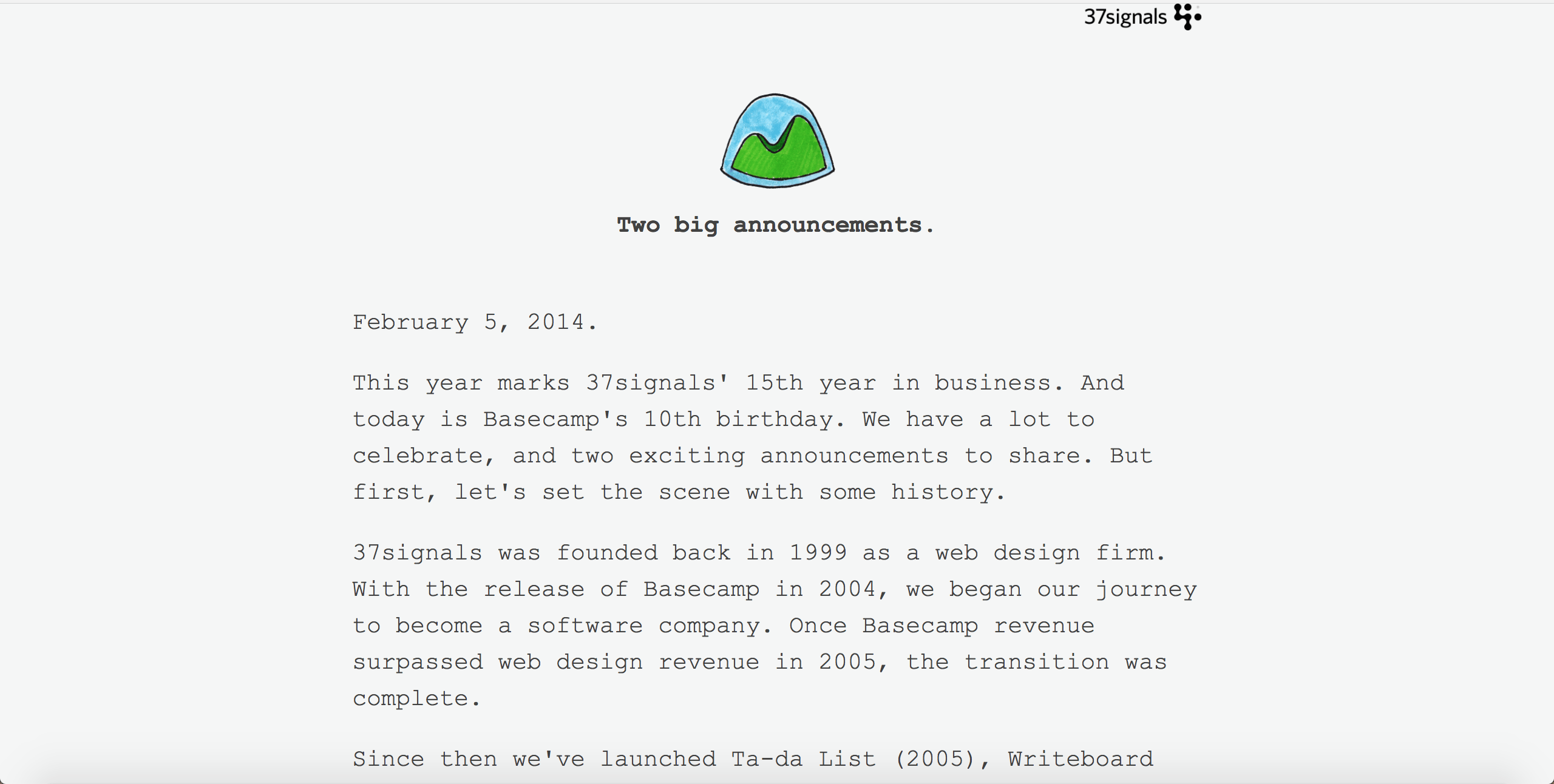

2005: Basecamp officially transitioned from a web consulting firm to a web applications company. They released a statement in 2014 reflecting that in 2005, the company was getting more revenue from Basecamp than from their design services. More importantly, the team (then four people) just “didn’t like” doing client work anymore. They took on their last project for a client in mid-2005 and haven’t done another one since.

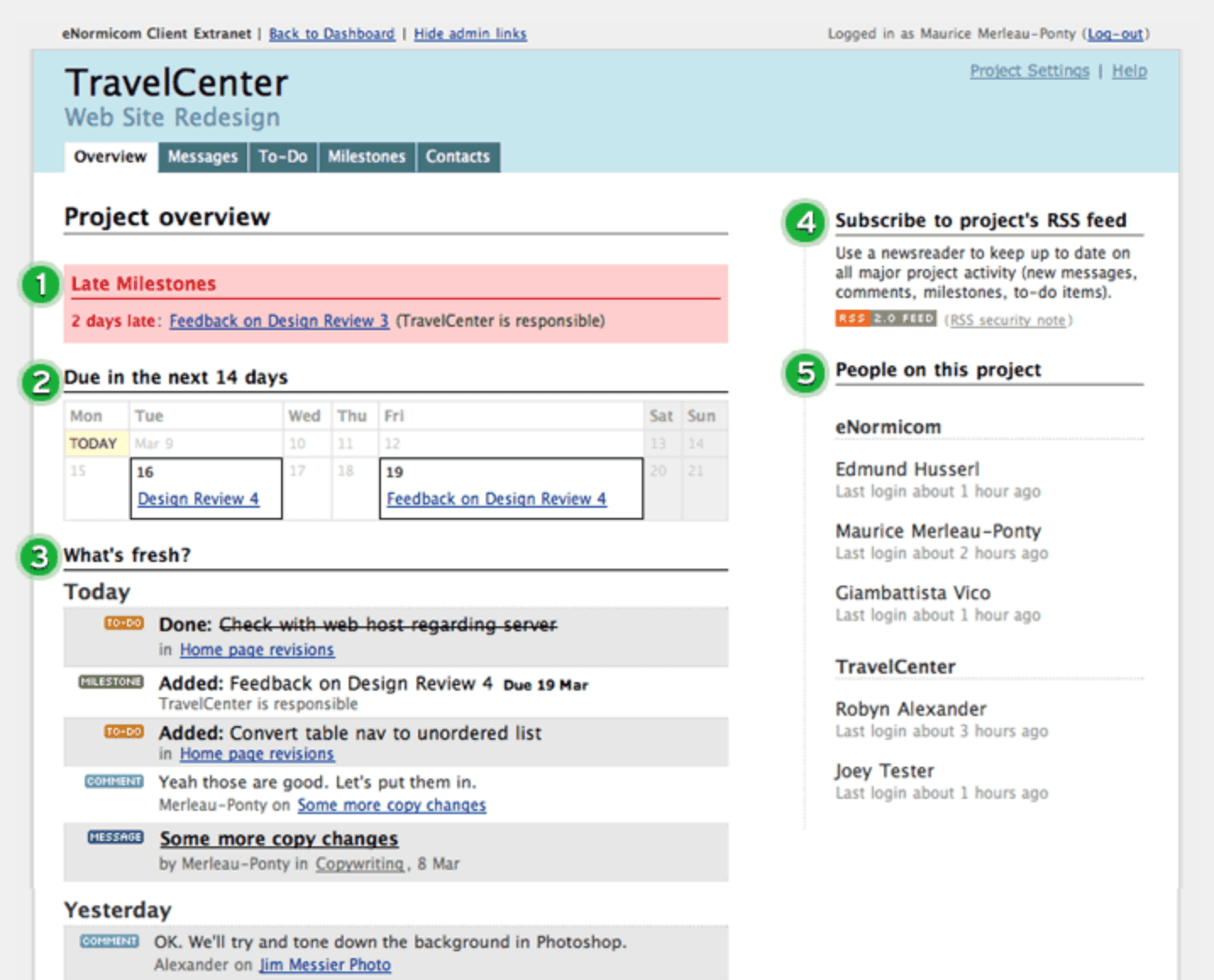

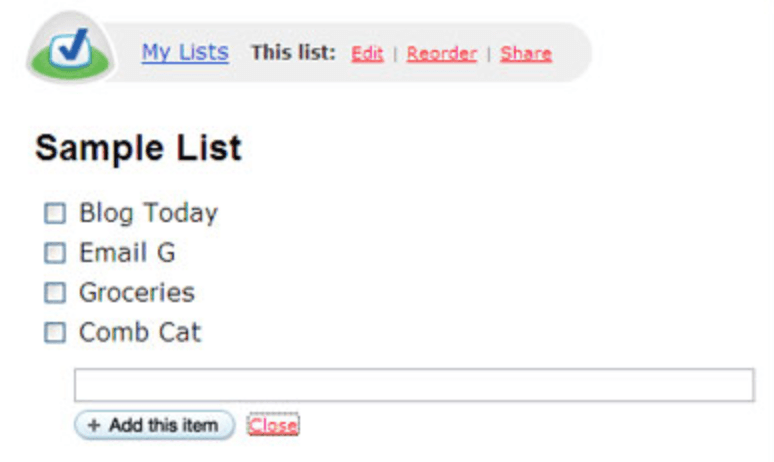

With all of their focus now on product, the team released their next web application. They built a fast and free to-do list app that could live in someone’s web browser and called it Ta-Da List. At the time, this was one of the only simple and free tools for to-do lists.

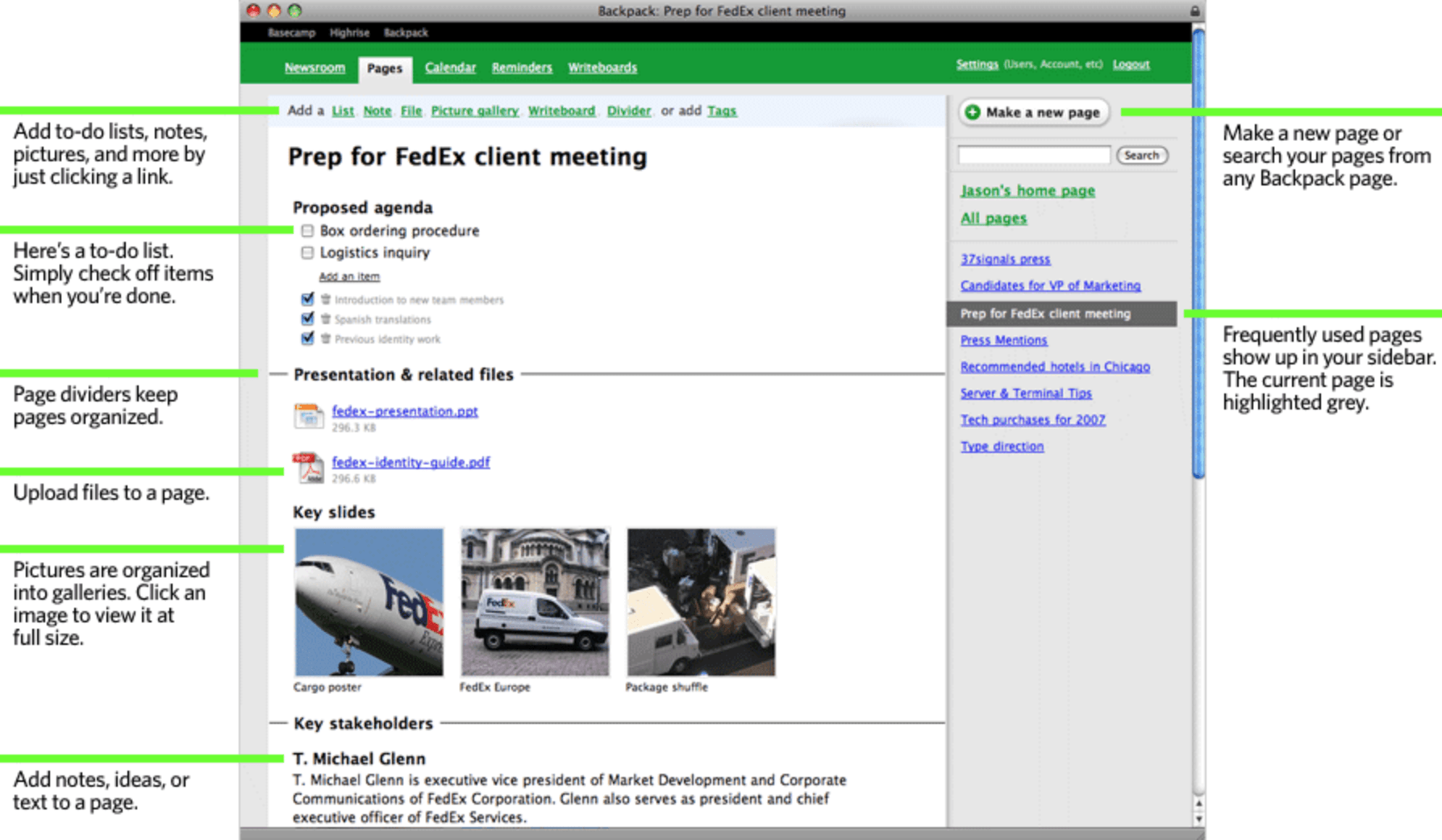

Next, they released a tool called Backpack, which was a way to manage different documents, files, and schedules.

The ideas for these apps came from expanding niche features in Basecamp. They were directly born from what the 37signals team thought would be useful for themselves, and therefore useful to other people. And in the relatively new SaaS environment, these simple tools were extremely helpful for users who could easily complete these basic tasks with simple tools that had never been available to them before.

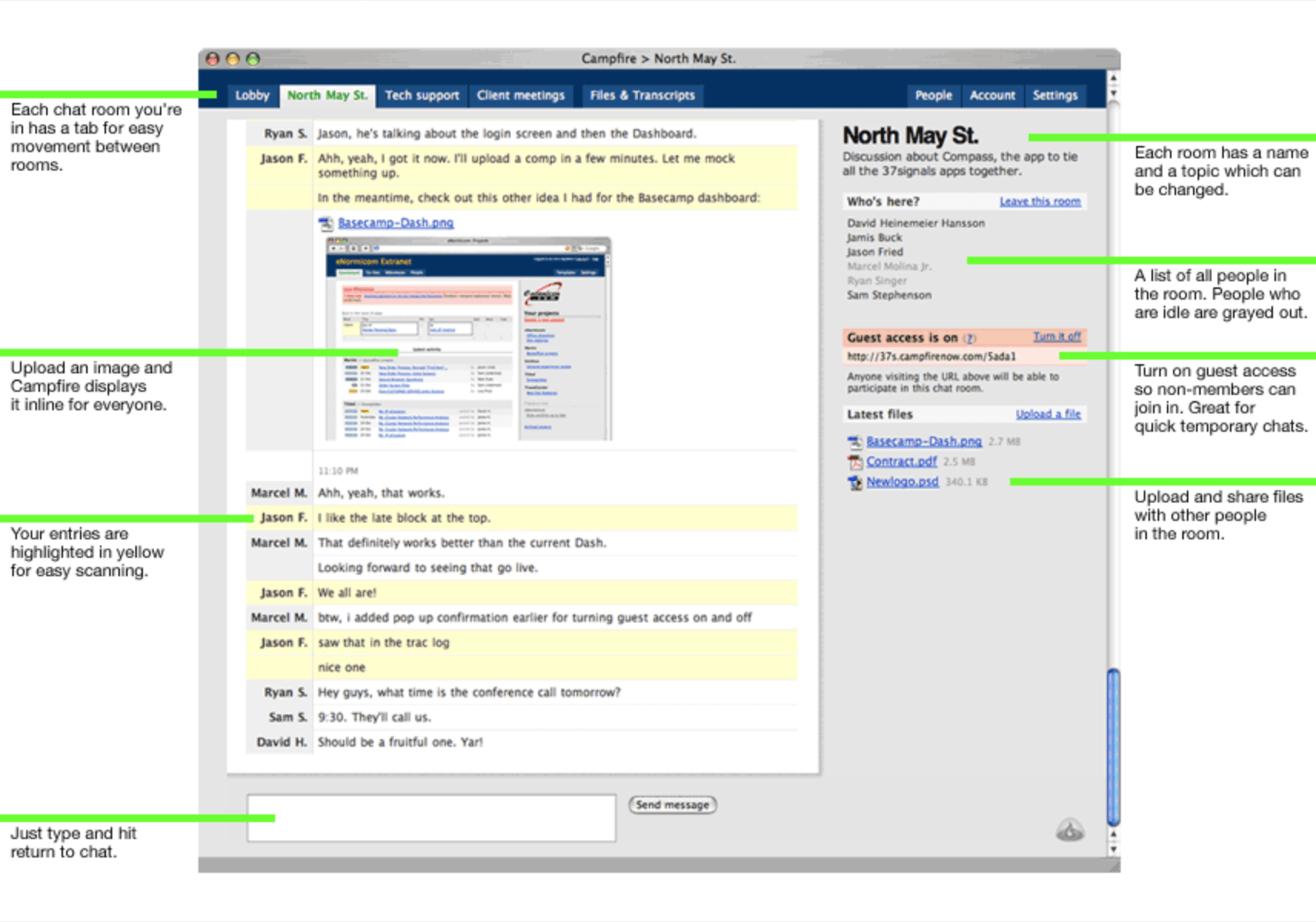

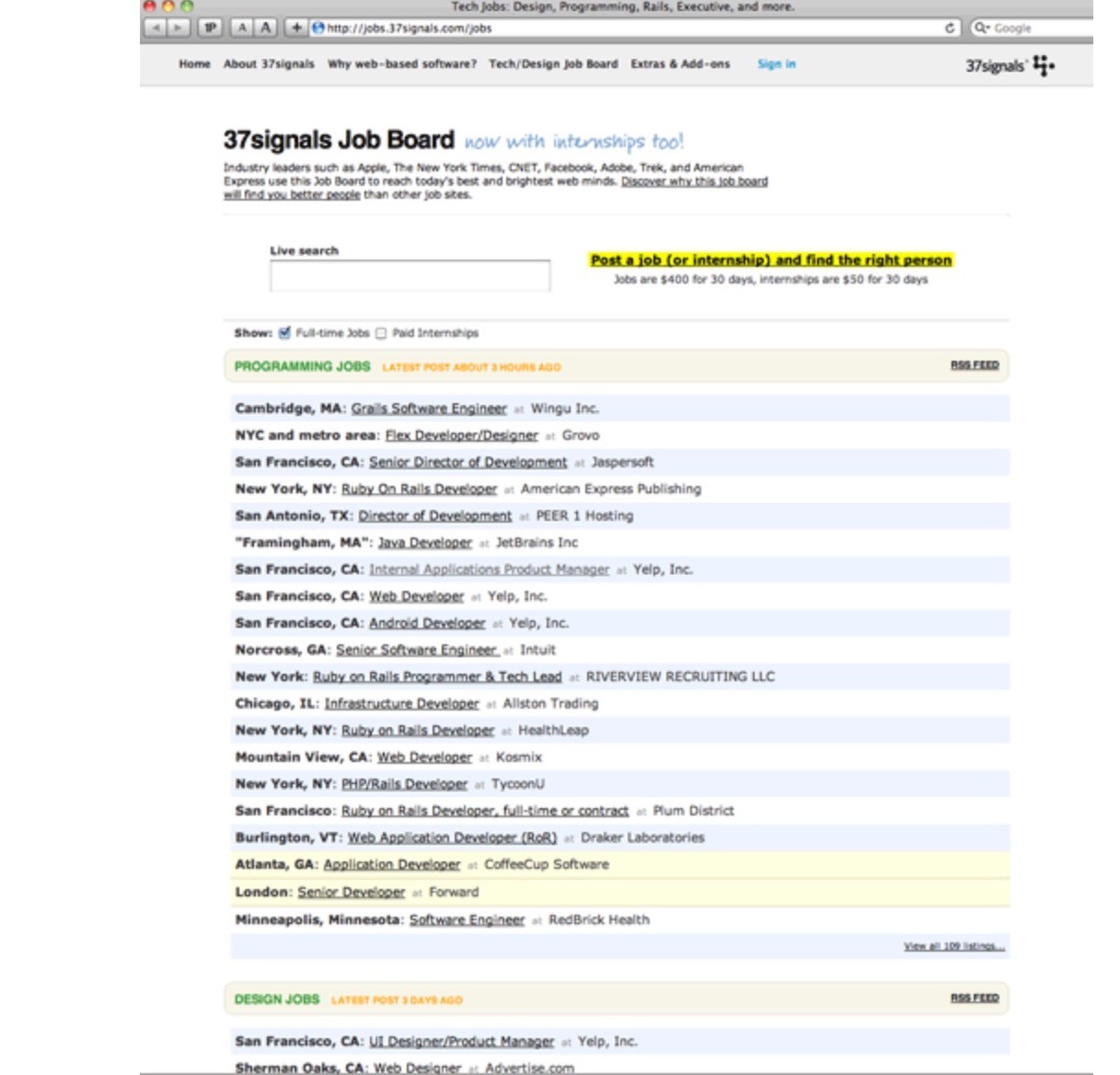

2006: The team at 37signals needed a real-time chat feature, so they built one. After using it internally for 45 days and deciding that they loved it, they released it as a product they called Campfire.That same year, they released Job Board and Gig Board, classified job and gig listing services for people who build websites. Since 37signals was growing as a team, this was also something that was immediately useful and relevant to them—so they knew other people would like it, too.

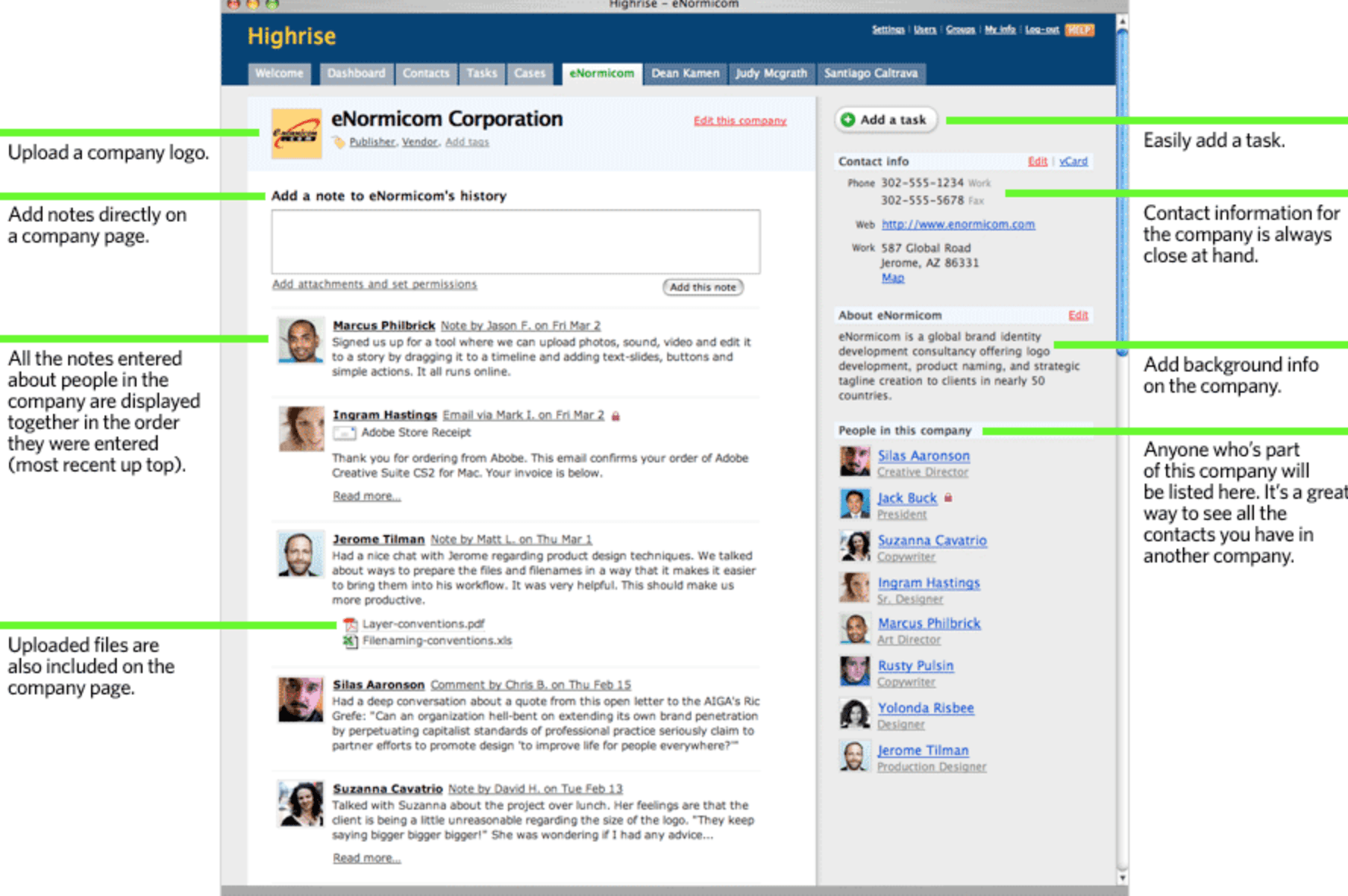

2007: The team launched Highrise, a bare-bones CRM. The CRM space was already getting crowded with bigger solutions like Salesforce and NetSuite. Highrise kept it really simple by focusing only on managing online contacts and integrating with ESPs like Outlook.

With their four main products—Basecamp, Campfire, Backpack, and Highrise—37signals was now serving over 1 million users.

2008: The company was growing financially and in team size. Fried wrote in a blog post that 37signals’ revenue was “doubling every year since the beginning,” but that this was not the goal and he didn’t expect it to last. The company had grown to 10 people, and they’d started experimenting with company policies that were pretty unheard of at the time for SaaS companies: four-day workweeks, company credit cards for everyone, and paying for flying lessons.

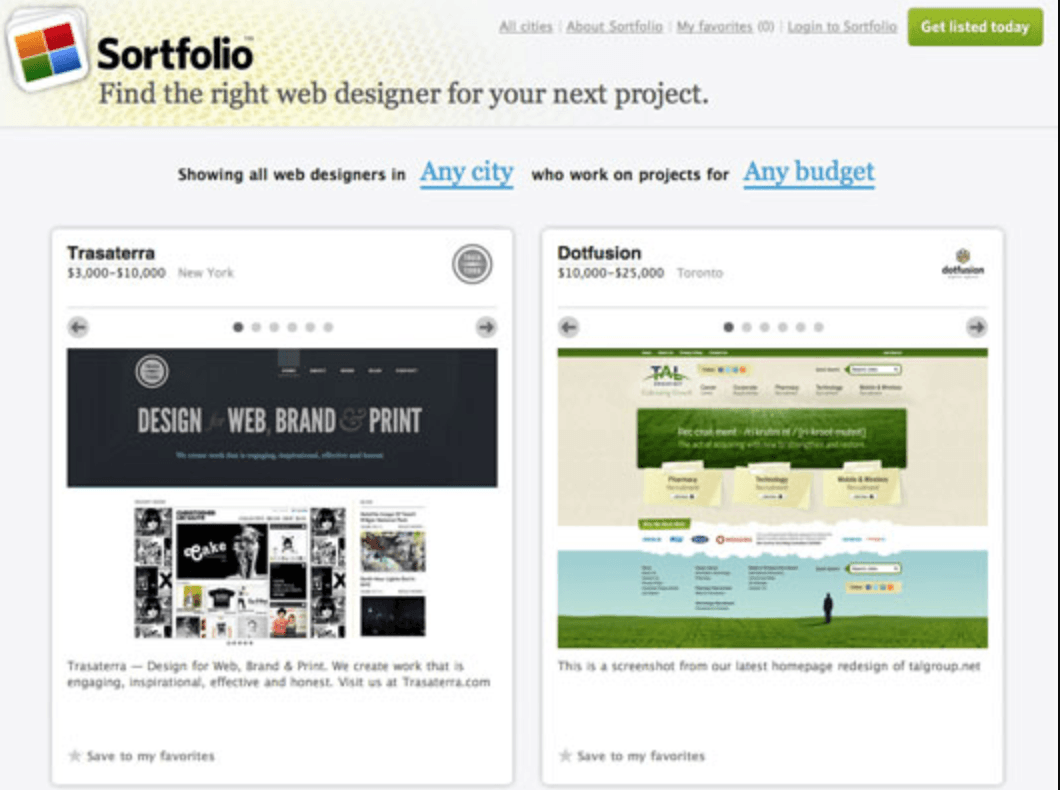

2009: The team created and released a web designer directory called Sortfolio. This idea came directly from the web design work that 37signals used to do. The goal was to help small businesses find designers—something that they knew from their old clients could be difficult.

Between all of their apps, 37signals now had 3 million users. The company continued to be cash flow positive.

Fried later called 2009 “one of their best years” in spite of the “nuclear winters of funding”—because 37signals never sought funding and always prioritized profit.

2011-2012: Sortfolio generated over $200,000 in profits in about a year for 37signals. Still, in 2012 they decided to sell it. The team didn’t feel like they had enough time to work on the product. It was profitable, but it wasn’t as profitable as the other products. So instead of half-assing their work on it, they sold it. Fried said:

“The bottom line: Profits aren’t everything. Sometimes you have to prune your winners. That way, you can focus your attention on your bigger winners.”

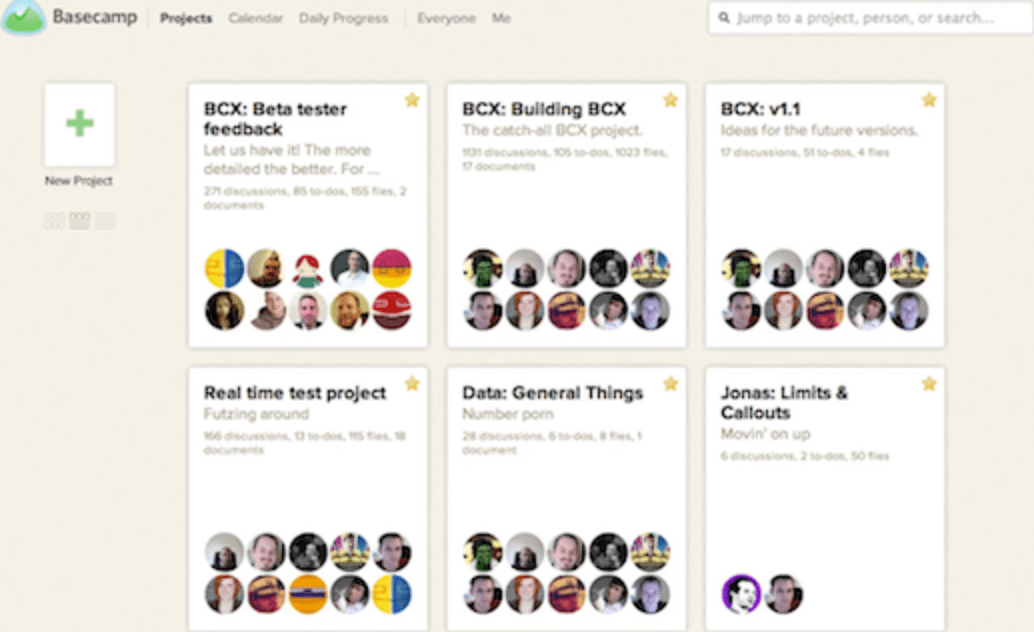

2012: After selling Sortfolio, the team began paying more attention to their biggest winner—Basecamp. Most of their revenue was still coming from this original product (specifically, 87% of revenue, 90% of revenue growth, and 90% of web traffic). So they doubled down and launched a redesign of Basecamp called Basecamp Next. They pared down the redesign, rather than beefing it up. They cut popular features like project templates, but they also made the interface cleaner, and the tool run faster.

The day after the release, 37signals received 1,500 customer service emails. Most of them were users asking where their favorite features had gone. Publicly, Fried and Hansson said the new Basecamp was focused on “speed, big picture, and focus,” and that they’d streamlined the product to make it more manageable for their 33 employees. But it was also a chance for the team to practice the radical software simplicity that they preached. In response to requests, the team continued to offer the original tool as “Basecamp Classic.”

2013: With over 1 million businesses using their products, 37signals continued to pare down. They retired Backpack, continuing to narrow their focus on fewer and fewer apps. They were preparing for a transition back to being a single-product company.

Basecamp’s decision to experiment with ideas, but then ultimately cut their side projects, may seem surprising given how a lot of SaaS companies start expanding product offerings and never look back. But Basecamp’s product, financing, and company development decisions at this time show that refocusing on one product wasn’t really surprising at all. They were just looking for ways to be more helpful to their users while still keeping things simple.

From 2004-2012, the team didn’t change the Basecamp product very much. They received lots of ideas from users and investors about how they could expand the product, but Fried and Hansson took a really firm stance in saying no to feature requests that didn’t align with their ideas of what would really help users. The most visible instance was when Fried denied a Basecamp user’s request to add Gantt charts to the product. He responded to the user’s angry blog post by writing, “We just have different opinions of what is required for good project management.”

Funding decisions at this time—in a stage of their development when many SaaS companies raise VC money—also reflected their commitment to simplicity. They never sought out VC money. The only investor they ever had was Jeff Bezos in 2006, who bought a minority, no-control stake. Fried and Hansson never had plans to build up and maintain a full suite of competitive products—so venture funding wasn’t necessary.

They were also unwilling to stretch their team to a point that could fully support a large variety of products. Fried was adamant that the team, now 36 people, not work 40-hour workweeks. They defined their company principles in a public company handbook, and took a lot of pride in sticking to their guns by only taking on as much work as was comfortable for the team.

Since they didn’t take any funding or expand the team, Basecamp was forced to grow within its means in order to stay profitable. Trying to maintain too many side products put a strain on that. Fried wrote:

“Because we’ve released so many products over the years, we’ve become a bit scattered, a bit diluted. Nobody does their best work when they’re spread too thin. We certainly don’t. We do out best work when we’re all focused on one thing.”

By taking what they’d learned from their “diluted” efforts and focusing them back on Basecamp, the company found their own way to continue helping users and continue making money.

2014-Present: Becoming Basecamp

While other companies are focused on the “next big thing,” like machine-learning, freemium tools, and chat bots, Basecamp is focused on constantly improving the engine of their business.

This goes back to advice that Fried got from Jeff Bezos at the start of the company: “Find the things that won’t change in your business and invest heavily in those things.”

That’s exactly what drove Basecamp to make the decision to transition back to a one-product company. When they made the announcement, Fried wrote:

“We’ll never forget what made Basecamp so popular in the first place: It just works. It’s simple, it’s easy to use, it’s easy to understand, it’s clear, it’s reliable, and it’s dependable. We’ll continue to make it more of all of those things.”

This goal for Basecamp—to make it more clear, reliable, and dependable product—isn’t tied to a specific time in the SaaS industry’s evolution. There’s definitely a freedom in this approach that many other mature SaaS companies have given up in exchange for revenue and fast growth.

Basecamp’s success isn’t shaped by what other companies are doing or what Silicon Valley says will be the next big thing. It’s completely reliant on Basecamp’s team, product, and customers.

2014: 37signals announced that they’re refocusing on just one product—Basecamp—so that they don’t have to dilute their efforts and can do their best work on a single product. They made Highrise an independent company and team, and stopped accepting new customers for Campfire. At this point, over 15 million people had Basecamp accounts, and new accounts were being added at a rate of around ~6k companies a week.

To drive home the one-product decision even more, 37signals officially changed their company name to Basecamp.

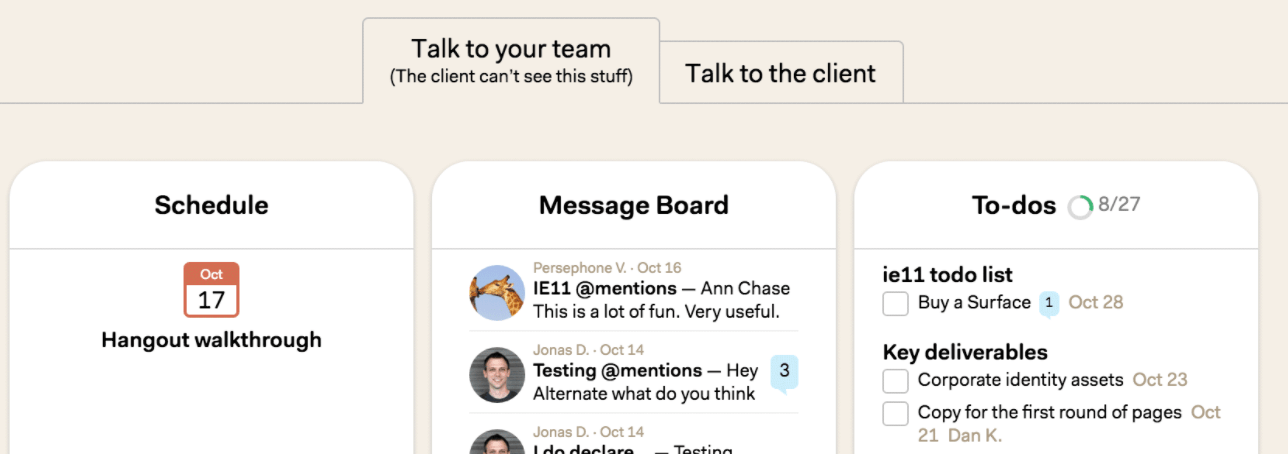

2015: The team launched Basecamp 3, an updated product that they’d worked on for two years. Straightforwardness and ease of use were still huge priorities. But in this version, Basecamp added some features that were meant to make work processes even easier. One important addition was a feature called Clientside, which helps companies keep external communications separate from internal communications. It is a useful feature for employees who have to interface with people outside of their team.

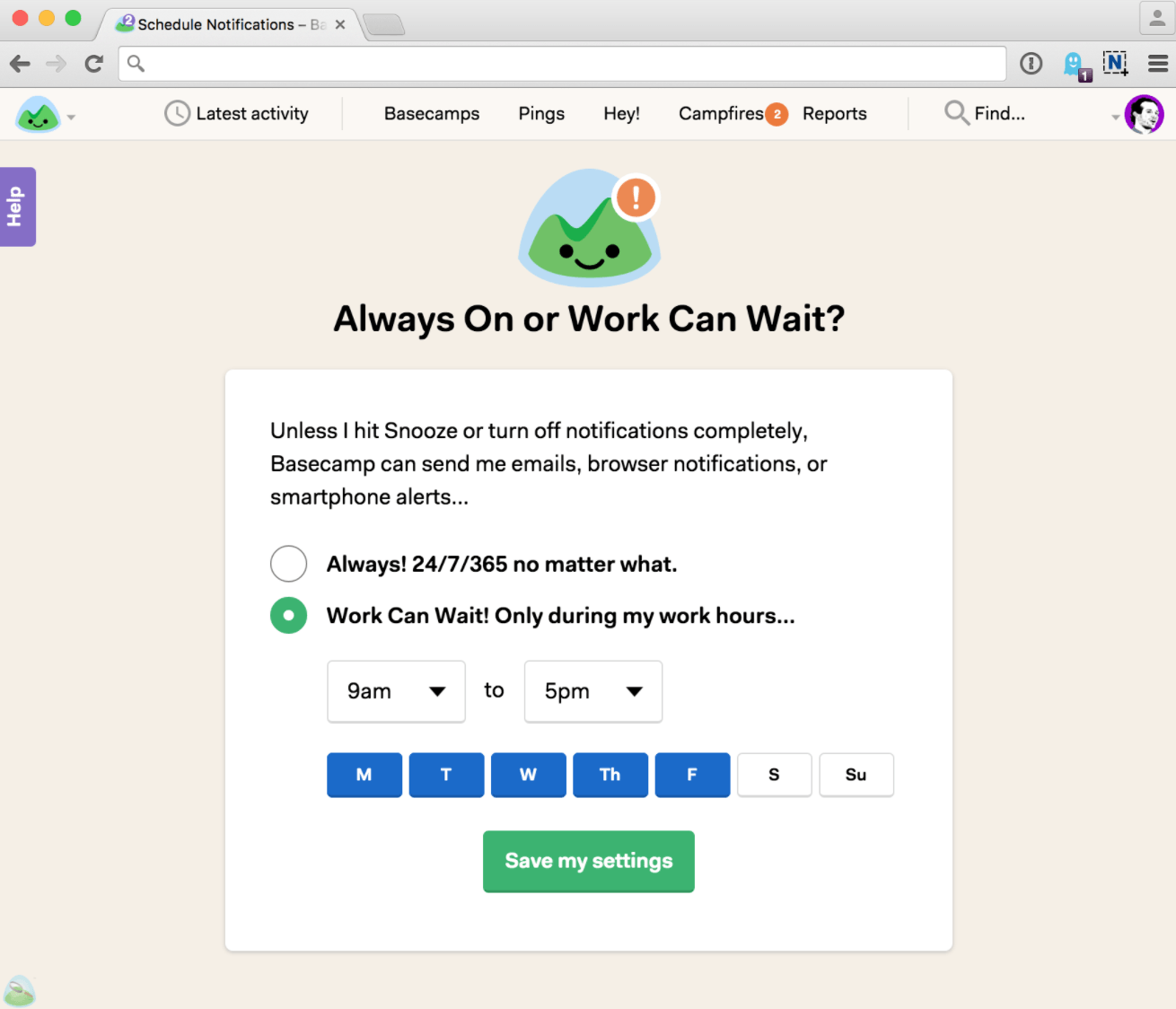

Another important new feature was the “Work Can Wait” setting. This lets Basecamp users choose time periods when they want to turn off notifications. This helped Basecamp users build in a healthier work-life balance.

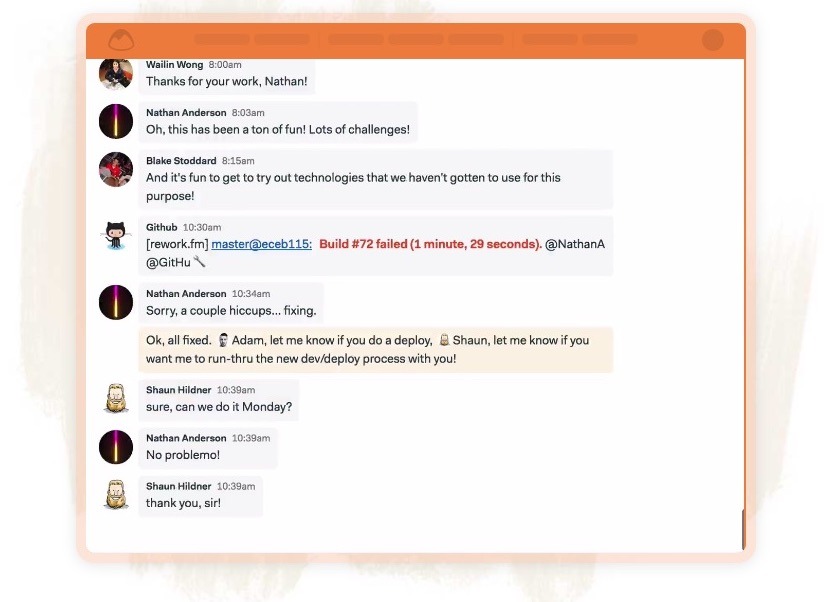

Finally, Basecamp 3 introduced Campfire chat as a part of the Basecamp product. The team saw how much customers loved live chat. They knew this addition would bring value to users—not just add product bulk.

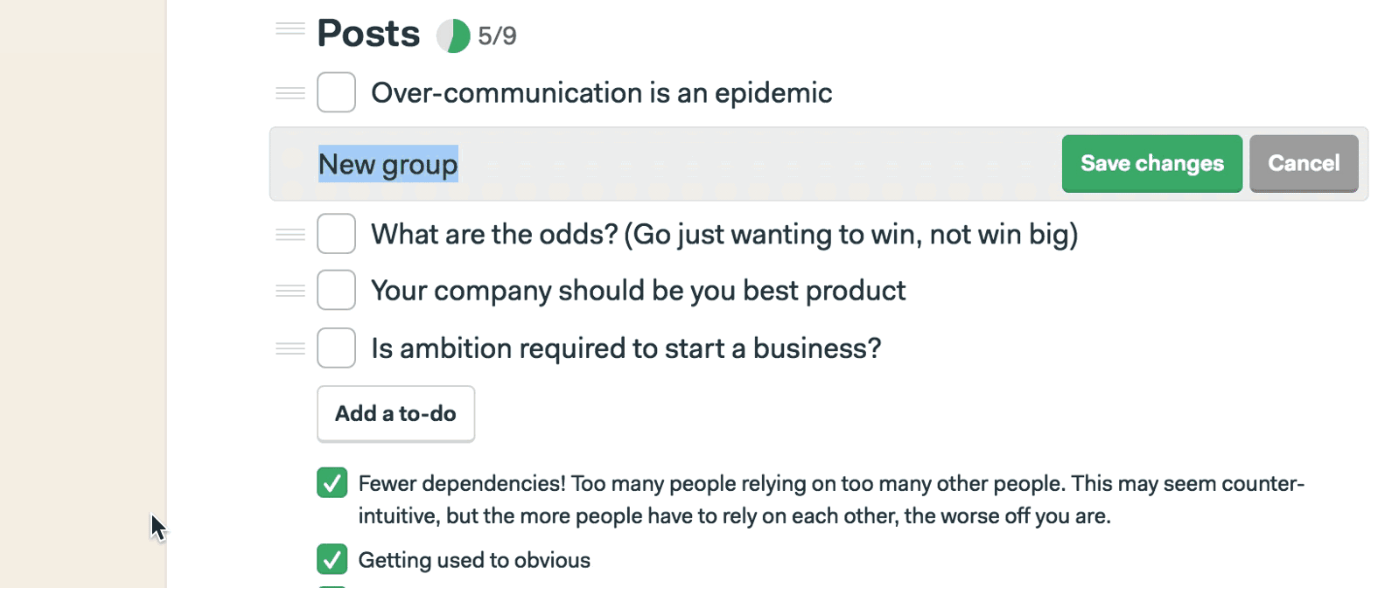

2017: The team kept working on Basecamp to improve what worked and prune what didn’t. Recently, Fried announced that they’d added a tiny new feature to Basecamp to-do lists: the ability to group individual tasks together within a longer list.

Fried wrote that they decided to add this feature the way they decided to add all of their other features: by incorporating and improving on “hacked patterns [the team] saw in the wild.” And one of the most important aspects of the feature release was that the to-do lists in Basecamp could stay the same for people who didn’t want to use groups, so the new feature didn’t have to overcomplicate the product.

For Basecamp, constantly improving isn’t about adding more stuff; it’s about making the product work better for customers. For example, even though they’ve released three versions of Basecamp, they continue to offer the original Basecamp Classic—and always plan to. The most important thing is giving users access to the version of the tool that works best for them.

This is why Basecamp’s brand has thrived and grown in the last 18 years. Product decisions reinforce their ethos, and on the company blog Signal v. Noise, they consistently explain how their philosophies drive product development and company culture. Some of the best examples of this:

- Press Release: 37signals Valuation Tops $100 Billion After Bold VC Investment

- Exponential growth devours and corrupts

- Why we choose profit

As of 2017, Basecamp is doing $25 million in ARR. This isn’t their all-time high—it’s fluctuated over the years as the company has released and cut products, released new versions, consolidated, and expanded. But for the past 18 years, they’ve been profitable. And they gladly have no idea how much their company is worth.

Where Basecamp can go from here

Basecamp is not going to grow along the traditional trajectory of SaaS companies. Many companies at Basecamp’s late stage will plan to build an enterprise product or move upmarket, if they haven’t already. But Basecamp refuses. They believe enterprise sales creates a big disconnect between the people building the product and the people buying it, and catering directly to users is still a top priority for Basecamp.

Basecamp’s growth will look different than that of most SaaS companies because most companies are chasing growth. Instead, the things that will guide Basecamp’s late-stage growth are the things that most SaaS companies don’t prioritize: longevity and profitability.

“So this brings us back to answering the question of why is growth inevitable [like most companies believe it is]? It won’t guarantee longevity, and it doesn’t promise profits. And aren’t those the two main, economic concerns of a business? To be ongoing and to make money? When I look at the business that Jason and I, and the employees have built in Basecamp, I can easily satisfy those basic, economic demands: We’re still here, and we’re still making plenty of money.” – David Heinemeier Hansson

With this in mind, here’s where Basecamp has potential to go next:

- Build an app directory: Basecamp already offers sample code and API documentation for developers who want to integrate with Basecamp. But there’s no centralized “app directory” for developers and users. An app directory wasn’t always necessary for Basecamp, but people use software differently today than they did 10-15 years ago. Users probably don’t just have one product management tool—they have Slack for chat, Front for email, Zoom for calls, etc. Making integrations more accessible and flexible with an app directory could help them future proof the business, making sure users can plug all of the other products they’re using into Basecamp.

- Create a consumer-facing product or service: One of Basecamp’s most important ideas about company development is that companies take too much time away from employees’ lives, and that they should try more to protect team members’ time and attention. Basecamp has already experimented with a B2B product to improve team members’ quality of work life, Know Your Company, a tool to help management connect better with their teams. They could expand to offer a B2C product that helps people manage their interests outside of work, like a project management tool for passion projects or a social calendar tool. This would help them continue building their brand of viewing employees holistically, and would give them insight into the different ways people define and manage work-life balance.

- Continue on their unpredictable trajectory: Basecamp has broken the mold. It’s been exciting and fun to see the company unfold by trailblazing new ways to build a SaaS business—from creating a spin-off product around team-building, to instituting 4-day workweeks, to publishing satirical fundraising announcements. The way they’ve developed their company and brand has been different than many and probably inconceivable to most. It’s so interesting to watch the company’s evolution and consider the possibility that they’ll continue to sustain their company in a way that’s totally unprecedented.

Basecamp’s possibilities for continued success are unconventional, considering the way that most SaaS companies choose to mature. But this is only fitting for a company that has rejected startup norms from Day 1.

3 Key Lessons Learned from Basecamp

The 37 core values that inspired the company’s original name had a huge impact on the development of the company and the product. But that’s only because Basecamp made key decisions along the way where they prioritized these values over adding more users, growing more revenue, and taking money from investors. They’ve defined their own version of success, and by all means, have reached it.

For anyone building a company today, there’s a lot that can be learned from Basecamp’s unconventional path:

1. Make the decision about whether to take funding based on your specific company, not the advice of others.

There are a million resources out there comparing the pros and cons of bootstrapping a company versus taking venture funding, and it seems like everyone has an opinion. I’ve founded bootstrapped and VC-backed companies, and I’ve found that the best path for each company is totally dependent on the goals of the founders and their vision for the product.

Here are some things to evaluate within your own company and among the founding team to help decide whether you want to take on venture funding:

- What are the early goals you want to optimize for? If you’re focused solely on product improvement and you already have the team members you need to work on your product, this creates less financial strain and makes bootstrapping easier. If you’re more focused on growing the number of users, you’ll have to invest more upfront in marketing and sales, which can be expensive.

- How big do you expect the company to be in 10 years? This means both in terms of number of products and team size. If you’re ultimately aiming to build an enterprise product and hold an IPO, venture funding makes sense. If you want to keep the team and product offerings small, it doesn’t.

- How important to you is it to have control over product and company decisions in the long-term? Taking venture funding will dilute your control over these decisions and introduce external pressures that shape product decisions.

2. Find a better way to build things.

Hansson first built Basecamp in 2003 using Ruby, a rarely-used programming language. He created a series of shortcuts that made it easier to use Ruby, and a few months after he and Fried released Basecamp as a public product, Hansson also released his shortcuts as open source to other developers. He called it Ruby on Rails.

Trying to build a better tool prompted Hansson to also look for a better way to build software tools. This doesn’t just apply to the language he was using. There are many factors that affect the building process, and if something isn’t working for you, addressing the problem in the process can help you create a tool that is more aligned with what you actually want to build.

If something is off in your building process, check for misalignment in these key areas:

- Coding style/programming language: Make sure everyone on your dev team feels comfortable with the coding language you’re using, and encourage developers to ask each other questions and address technical problems as they come up.

- Design philosophy: There should be top-down alignment on product design and UI. In the case of products like Basecamp, design is hugely important to the product’s function and the company’s brand, so you need to have a good method for communicating among the team how design is implemented in the product.

- Team dynamics: I’ve personally experienced the friction that can occur as a non-technical founder when you hire a developer and can’t get aligned on what or how you’re trying to build. If you’re non-technical and you’re hiring developers to help you build, make sure you have a thorough conversation with them about goals and working style before you start working together.

3. Underdo your competition.

Basecamp has faced a lot of competition in the project management space. This is especially true with the rise of free tools, because Basecamp is insistent on continuing to charge money and generate profits.

For example, the project management tool Asana has taken a completely different approach to building their company. They offer a basic version of their tool for free, and have premium plans for the enterprise version of their product.

Basecamp’s response to competition has been to “one-down” instead of one-up. In their book REWORK, Fried and Hansson wrote:

“Conventional wisdom advises you to do more than your competition but this might not be true always. Whatever you do; do it well! The one-upping, cold war mentality is a dead end; instead try one-downing. Do the simple things better.”

To put this into practice, go back to Jeff Bezos’ advice that he gave Fried and Hansson: “Find the things that won’t change in your business and invest heavily in those things.” Start talking to your earliest users and ask them:

- Which feature would you miss the most if we removed it?

- Which feature do you think is most useful to you every day?

- Which feature could you see yourself still using 10 years from now?

Basecamp will still keep it simple, whatever that means

Basecamp tosses around the idea of simplicity a lot. Fried has tried to shed some light on what it means to the company:

“Simple is a tricky word, it can mean a lot of things. To us, it just means clear. That doesn’t always mean total reduction, or minimalism—sometimes, to make things clearer, you have to add a step.”

Over the last 18 years, Basecamp has proved that they work and build with simplicity and clarity. Even though the company trajectory has looked very different from other successful SaaS businesses, they’ve been wildly successful—and not just in building a SaaS product. They’ve defined a mentality and work culture that has inspired other companies in and outside of tech. And because of this, I’m very excited to see what they do next.