How Atlassian Built a $10 Billion Growth Engine

“We’ve had a lot of smart people who wouldn’t join the company or give us money or advise us because [our business] made no sense to them.” — Mike Cannon-Brookes, Atlassian co-founder

When Atlassian was founded in 2002, the founders had a choice to make.

They could jump through the standard hoops and do the things that most SaaS companies were doing—build out a sales team, knock down investors’ doors, and try to turn an idea into millions of dollars in funding.

But, Atlassian didn’t jump through the standard (and expected) hoops. Instead, they chose an unconventional path that would ultimately help them build a $10 billion business.

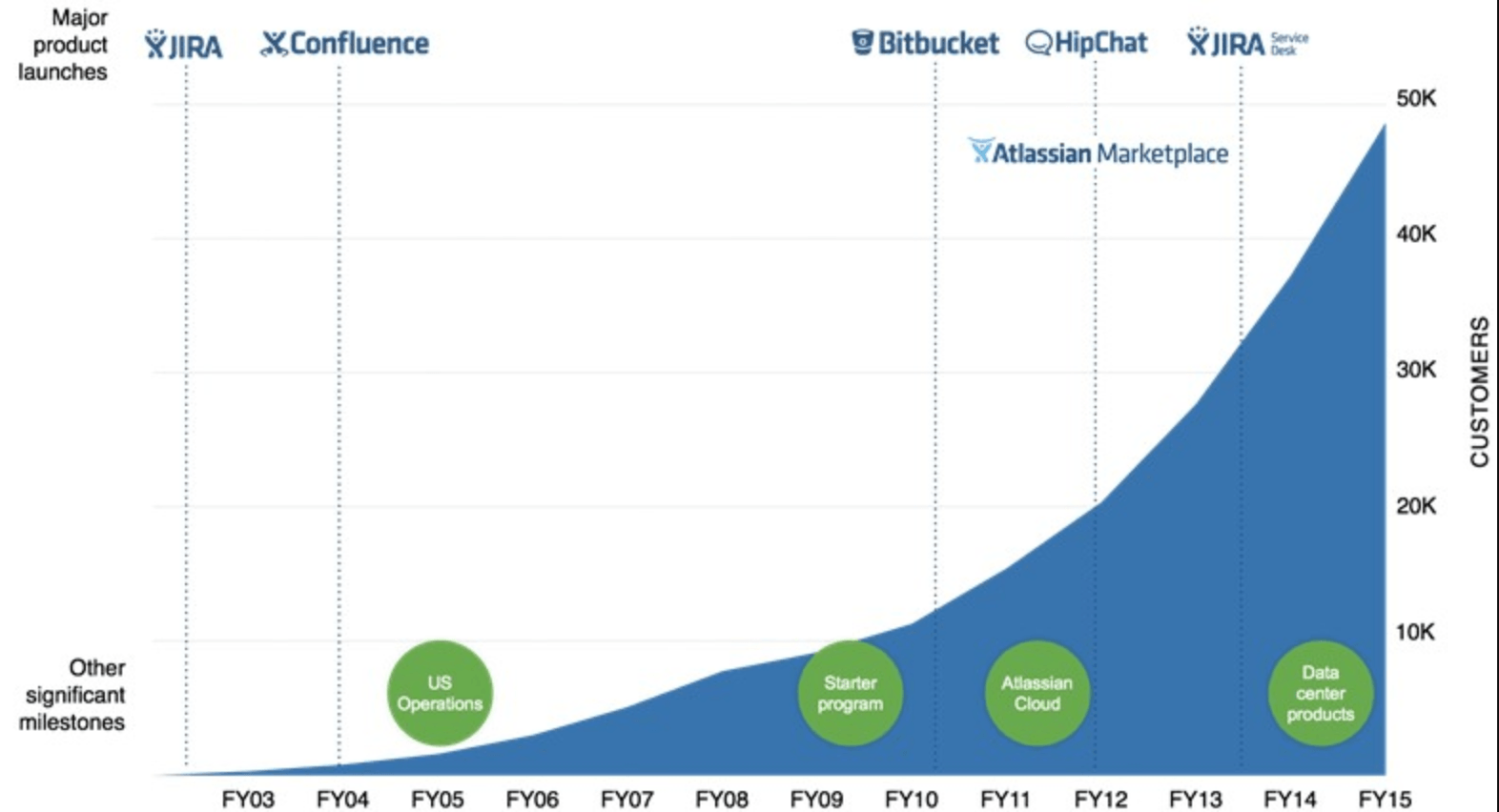

Atlassian still doesn’t have an enterprise sales team 15 years into the company’s founding. But their biggest—and most unusual—lever for growth has been to consistently acquire other products throughout the company’s history and integrate them into the existing product suite. This has helped Atlassian grow into a family of products that can spread organically through enterprise organizations.

How exactly has Atlassian created a growth engine around acquisitions and integrations to build their behemoth global business? Let’s dive deeper into how the company:

- Developed a loyal market by building a best-in-class project management tool for engineering teams

- Strategically expanded their product offerings through acquisitions to broaden their customer base to teams around the dev teams

- Doubled down on freemium distribution and horizontal use-cases in their recent acquisitions to make the top of their funnel even wider across teams

So many of Atlassian’s strategies were unique for their time, but have since become common practice for SaaS companies. Let’s take a look at how several of these practices were developed out of Atlassian’s specific needs throughout the company’s lifetime, and how each one helped shape the company’s success.

2002-2010: Self-funded and freemium

In 2002—the tail end of a nuclear winter for tech—being a Silicon Valley entrepreneur was tough. But being an entrepreneur in Sydney, Australia was much harder. There wasn’t a large tech community, and there weren’t local VCs that founders could go to for investments. Atlassian co-founders Mike Cannon-Brookes and Scott Farquhar put it this way: there was no IPO preschool like there was in Silicon Valley.

So with an idea for a new developer tool and no money, they realized that building a successful company meant two things:

- They had to create really useful tools quickly so they could win over the market

- They had to find a way to sell them without paying for a sales team

Since they were developers themselves, the co-founders saw the need for developer-specific tools around tracking issues and collaborating with one another. They built these functions into their first two tools—Jira and Confluence.

No one had built project management or collaboration tools yet for developers, and the co-founders knew from their own work that other developers would want these tools. All they had to do was get them to try it. They decided to use a freemium plan to allow people to test out the tools without risk, and realize for themselves how useful they were.

This model allowed a lot of people to start using the tools really quickly—and as they onboarded more customers and grew revenue without sales overhead, they were able to start acquiring other companies and adding to their developer offerings very early on in their company’s lifetime.

Let’s take a closer look at how they built—and acquired—these initial products in the early years to win over the developer market.

2002: Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar both studied computer science and met in college. They knew they wanted to start their own company, and they began by creating a third-party support service. On the side, they built their own issue tracker because they were fed up with using email or personal productivity tools to track their developer work. Doing developer work is messy and they needed a concrete place where they could log issues and work collaboratively. Soon, they realized what they built had the potential to be really useful for other developers—and they decided to pivot from a service company to a product company. They took out $10,000 in credit card debt to start Atlassian, and launched that first flagship product, Jira.

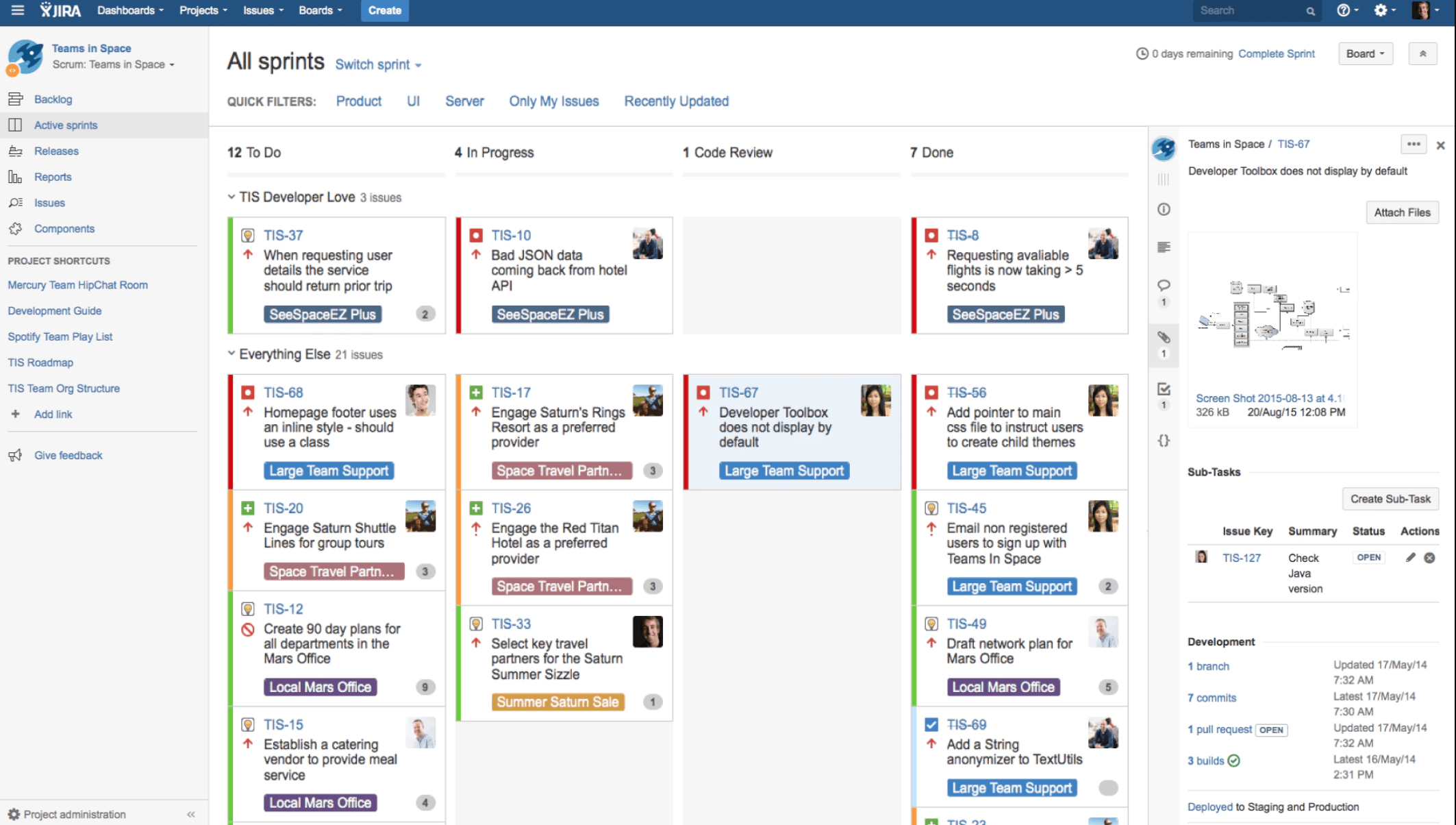

Jira featured a simple interface and provided developers with a single place to manage bugs, plan features, and track tasks. Jira also featured version-history, file attachments, and a search function for issues—everything a developer needed to manage software projects in one place. This hadn’t been possible before with other tools.

Because of Jira’s comprehensiveness and complexity, the product came with a steep learning curve. But this was actually a blessing in Atlassian’s specific market. The thing that made the product challenging to learn was what developers loved most about it—that it did everything needed for issue tracking, and they could customize it to work precisely the way they needed it to for their specific teams and projects.

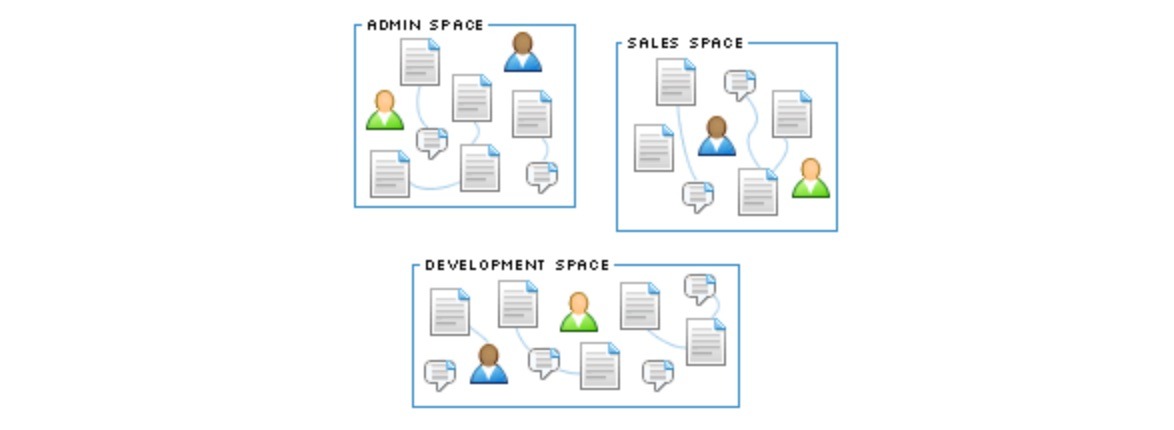

2004: Jira was bringing in revenue, but even in these first years, Atlassian was on the lookout for other potential revenue streams. Wiki technology was gaining traction in the developer market—the Atlassian co-founders took this as their opportunity to provide simple wiki functions to teams with the requirements of enterprise knowledge management systems. They called this new dev team collaboration platform Confluence. It was for the kinds of teams that would also use Jira, and was meant to provide more value by making wikis easy to create, edit, link, search, and organize.

Confluence also integrated really well with Jira, which developer teams were already starting to love. It worked seamlessly with another really specific, useful product, which motivated teams to give Confluence a try.

The decision to build a second product after the initial success of Jira was risky because many early-stage companies focus all of their attention on a single product. Dividing resources could have meant that both products would fail. But the team had faith in how much users liked using Jira, and recognized that there were still other helpful tools Atlassian could provide. The multi-product strategy paid off. As Cannon-Brookes said: “We had two rocket engines driving us along, not just one.”

2005: Just three years after its founding, Atlassian was profitable without having taken any venture capital. This was because they charged enterprise prices and didn’t have to spend money paying sales people: they sold the product by providing an option for a 30-day free trial on their website, and then gave trial users the option to get on a paid plan. This allowed developers to try their products out, realize how useful they were, and then recommend the products to their team members and developer friends.

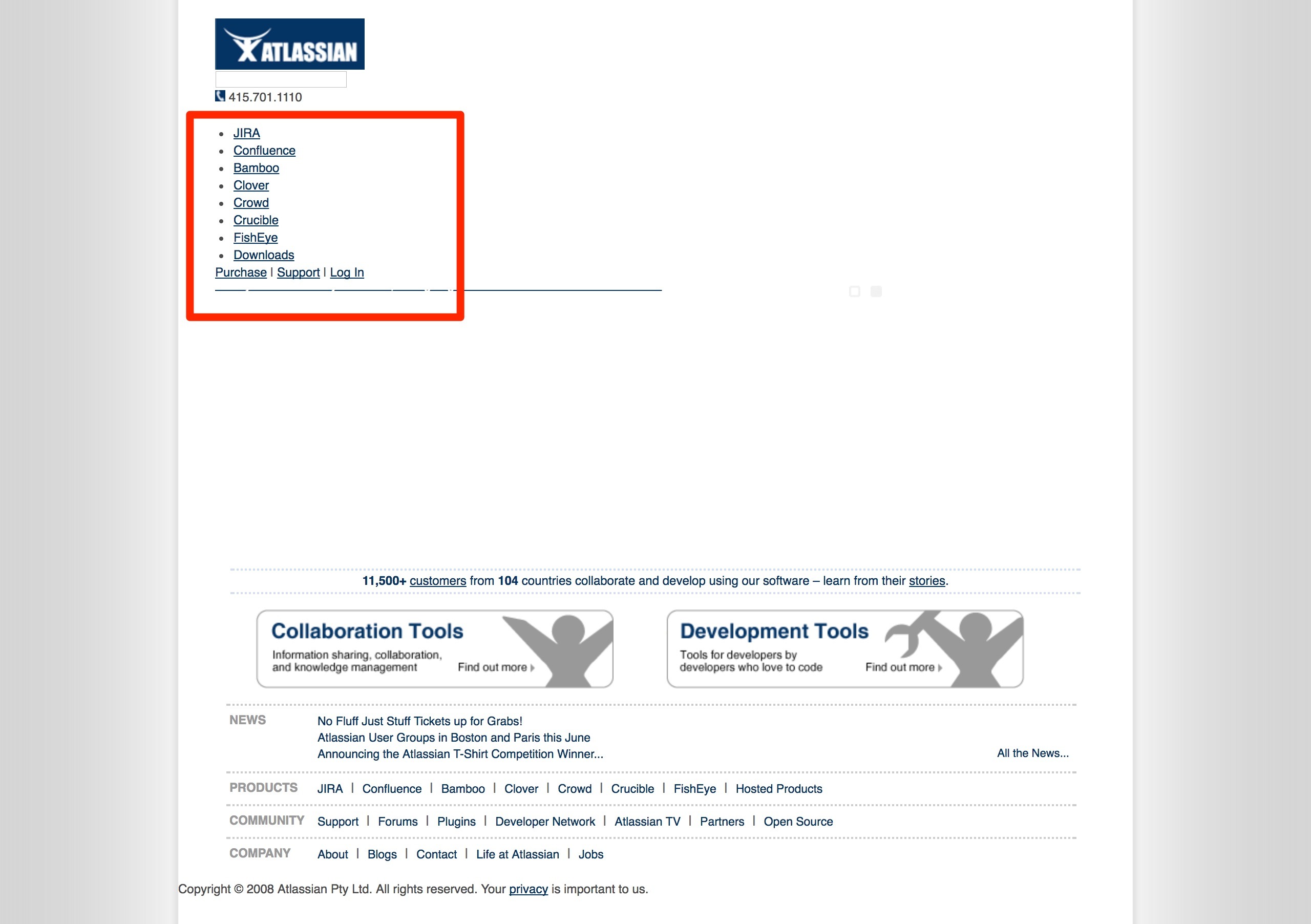

2007: At this time, both Jira and Confluence sales were growing, and this validated that the developer market was a space with a lot of opportunity. But here’s where Atlassian made a really interesting, unique move. The typical way for enterprise developer tool companies to expand is to build more products. Since Atlassian had capital, they decided that instead of spending time building more of their own tools, they’d buy ones that were already successful.

This lead them to look to the company Cenqua, which made three developer tools—Fisheye, Crucible, and Clover. These tools filled the gaps in Atlassian’s product offerings. Cannon-Brookes noted that some of the functionality of these tools, like Crucible’s code review, was incredibly valuable to developers. He said that “on a scale of one to ten, the strategic fit [of the Cenqua tools] is a ten.”

They integrated these products into their offerings by allowing the services to continue uninterrupted, but moved all of the products’ information and documentation over to the Atlassian site. All of Cenqua’s development and executive staff moved over to join Atlassian. By 2008, The Crucible tools were listed alongside Atlassian’s other product offerings on Atlassian’s website as part of a cohesive product suite.

Making such an early acquisition was unusual, especially given the company’s lack of venture funding. But Atlassian’s freemium sales model had helped them quickly generate a lot of revenue. When they weighed the pros and cons of the time and money it would take to build out their own version of those tools, the company saw the acquisition of Cenqua as the best use of their resources at the time.

The freemium sales and distribution model, as well as the early acquisitions, created many revenue streams that lead to over $50M in ARR by 2010. At this point the company was eight years old and had already been profitable for five years.

It was clear that Atlassian didn’t need venture money to survive—they’d built an engine that could survive on its own. But in their long-term plans for the company, they had their own unique reasons for wanting to work with investors in the next stage of growth.

2010-2015: Integrating acquisitions and spreading to other teams

“We want to build a 50-year company. Going public is one step on that journey. There are very few long-term companies that are private.” – Scott Farquhar

Unlike a lot of companies, Atlassian didn’t raise money because they needed cash—they’d already built a model for a healthy business by winning over the developer market with useful tools.

The early success of Jira, Confluence, and the Cenqua products encouraged the team and proved their freemium distribution model could work. They realized that by building a suite of products developers needed, they could become indispensable to customers and retain them long-term. Given the success of the first acquisition, the company decided the best path forward was to become exceptional at acquisition and folding useful pre-existing products into the Atlassian suite.

Here’s what Atlassian did during this time to acquire the right products, integrate them well, and continue expanding their user base to users that were tangential to dev teams.

2010: Atlassian raised $60 million in secondary funding from Accel Partners, eight years after starting their company. They planned to use the money from the investment to add to their war chest for acquisitions and growth. The team stated that capital would go toward M&A with other enterprise tools. These additional tools would help them provide even more functionality to enterprise developer teams, and start to widen into other verticals.

At this point, Atlassian had over 20,000 customers worldwide, including Facebook and Adobe, and were feeling the need to offer an even more robust and comprehensive set of developer tools. So in an effort to start doing “what Adobe does for designers, except for technical teams,” Atlassian looked at how they could help developers manage their projects at other stages in their pipeline.

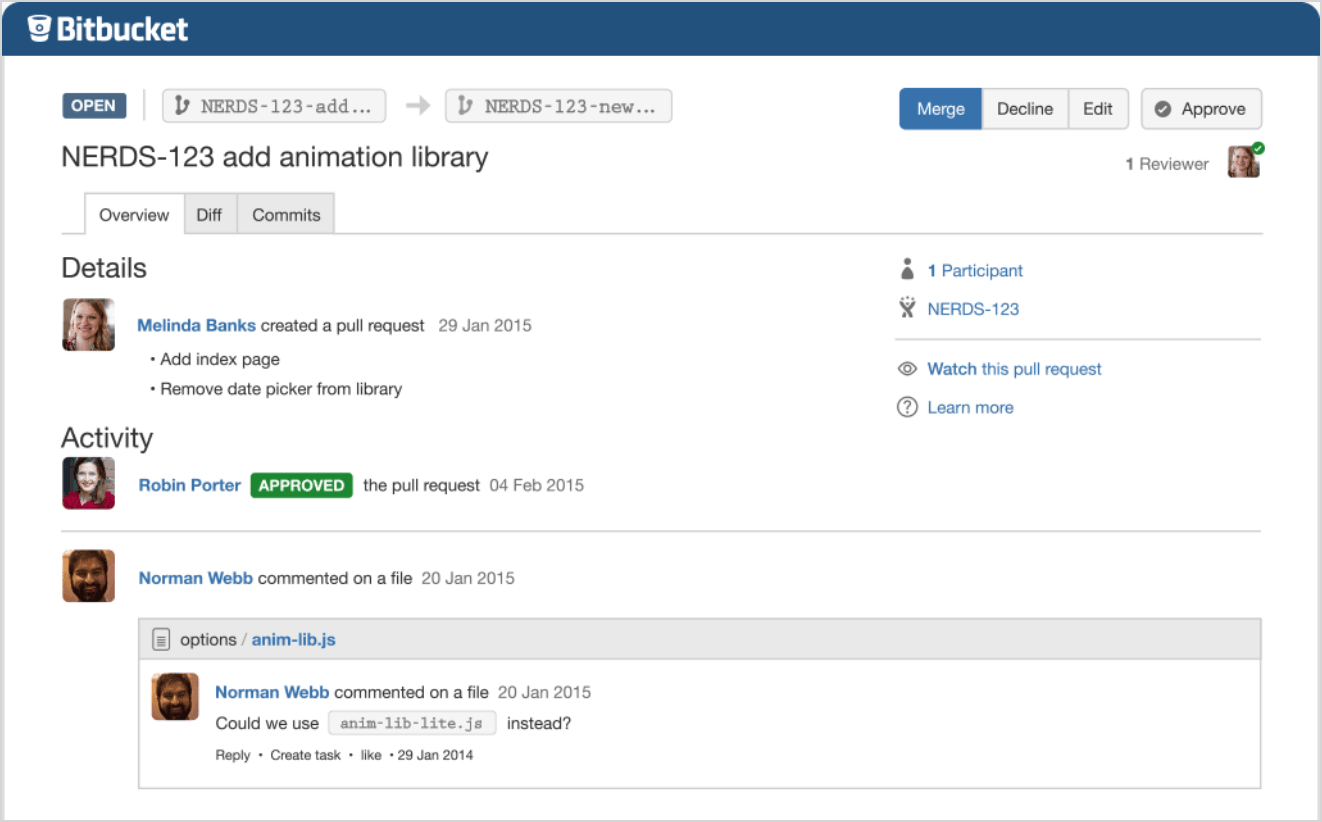

This lead them to acquire Bitbucket, a hosted service for code collaboration, for an undisclosed amount. Bitbucket helped developers share and collaborate on a decentralized software repository. As one report noted, thanks to the Bitbucket acquisition, developers now had “a place to dump and host their code, and a place to track their project issues and bugs within Atlassian.” It was a perfect product fit to fill a gap in Atlassian’s offerings. Atlassian offered the product right alongside all of the others, and created new pricing tiers—including a freemium plan—to fit seamlessly into Atlassian’s existing freemium distribution model.

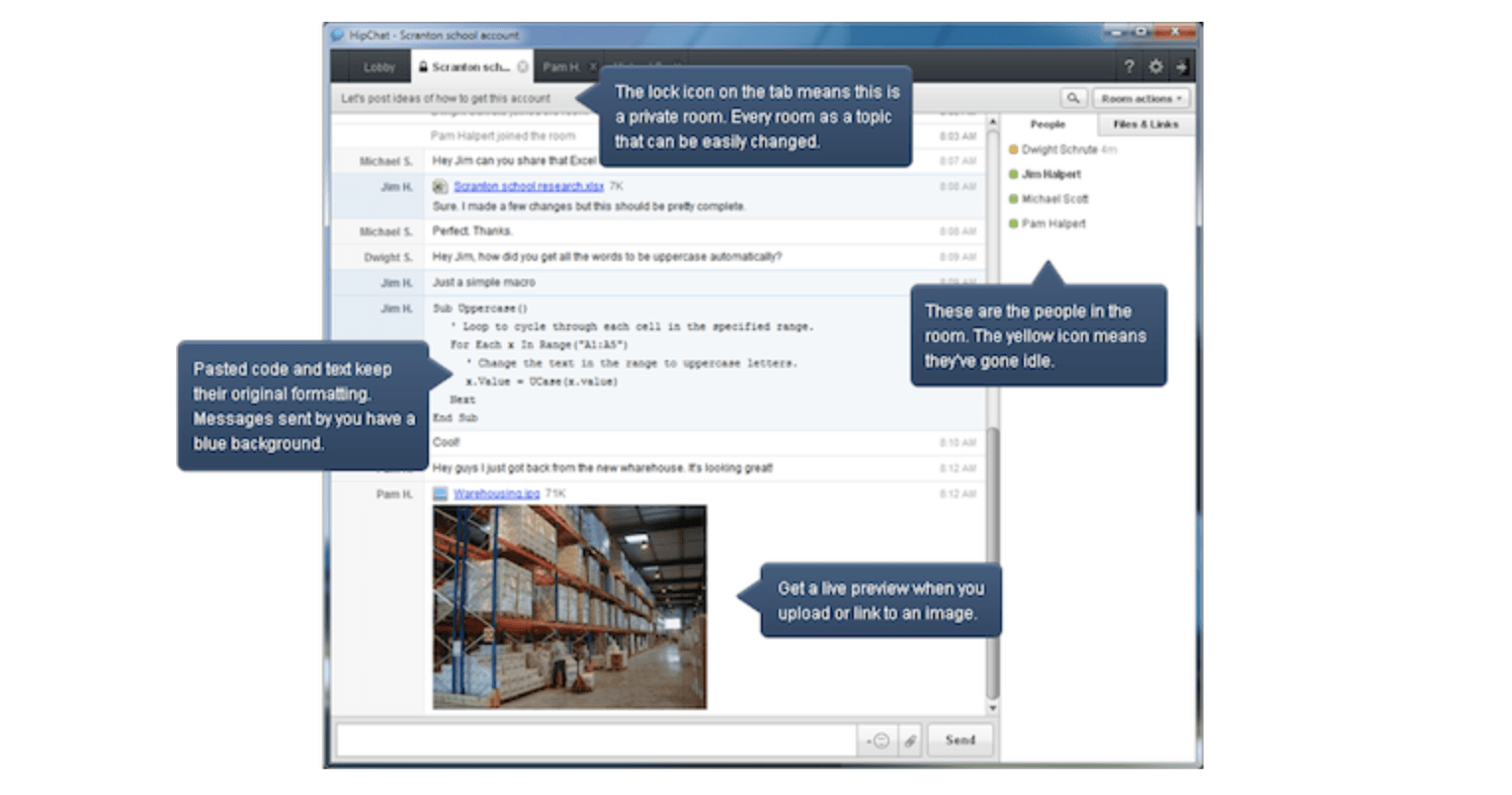

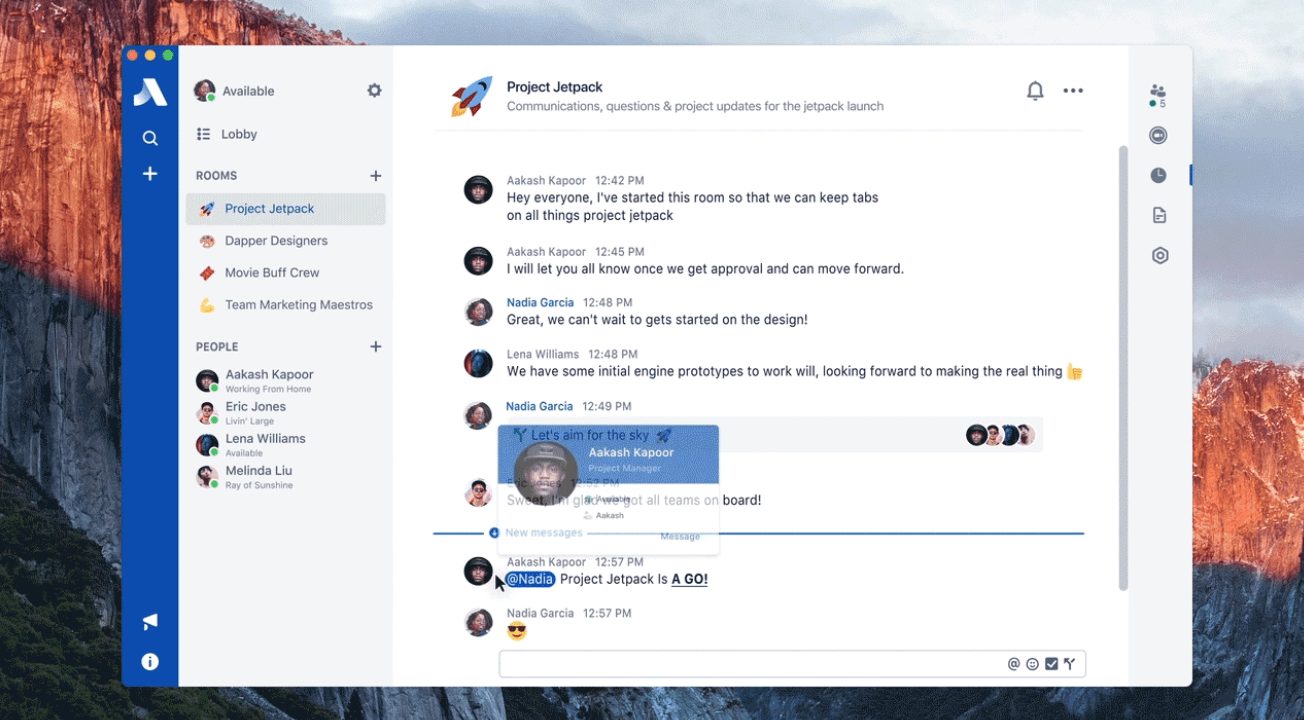

2012: Atlassian acquired the hosted private chat service Hipchat, and announced a plan to integrate the chat feature into its suite of products. This was a brilliant move that showed Atlassian was ahead of its time—Slack had not blown up yet and a real-time communication tool wasn’t an obvious acquisition. However, Atlassian used Hipchat on their own team and knew how useful it was, so they wanted to provide the same integrated functionality to their users, too.

HipChat was growing quickly at the time and had over 1,200 customers of their own, including Groupon and HubSpot. The product was helping entire organizations communicate. Pete Curley, the CEO and founder of Hipchat, said that Atlassian was the perfect environment to continue scaling Hipchat’s services quickly, noting “the no-friction business model.” Acquiring Hipchat was the perfect way for Atlassian to plug another a hole in their product offerings and get more non-developer teams to start using Atlassian products. As Cannon-Brookes put it, Hipchat is “perfect for product teams but fantastic for any team.”

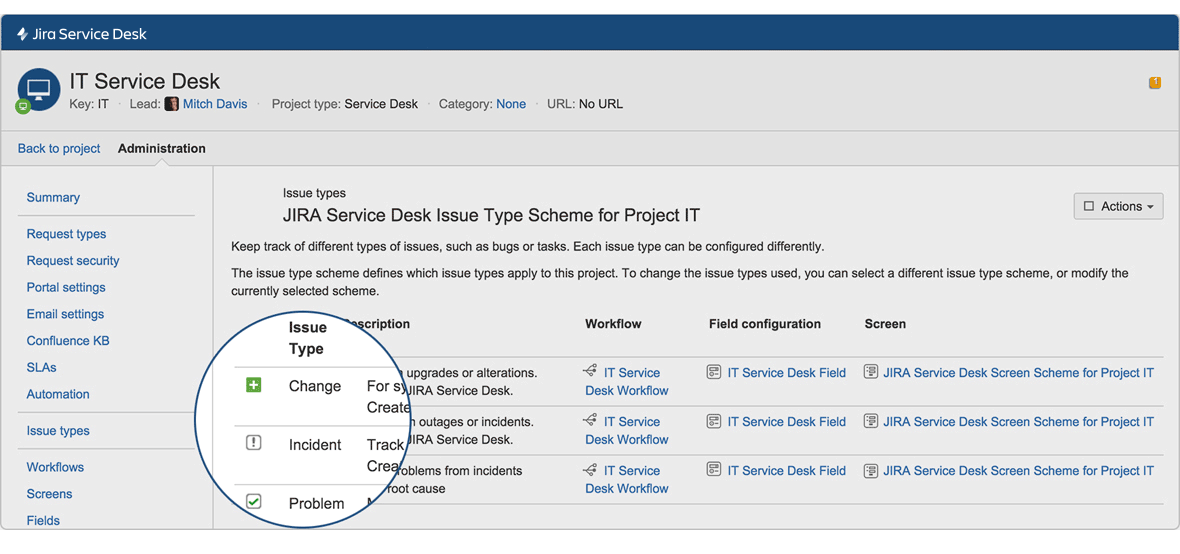

2013: Atlassian released a service desk offering on top of Jira that targeted the IT market. The new features included a customer-centered interface, an SLA engine, customizable team queues, and real-time reports and analytics.

At the time, Atlassian president Jay Simmons said that this addition was an organic extension based on the needs of Jira customers. About 40% of Jira users had already extended Jira to service desk and help desk use cases and had asked Atlassian to build the service. The service desk helped extend Atlassian’s offerings to IT departments and continue growing bookings, which at this time were over $100 million a year.

2015: Atlassian’s Git services were fast growing—Eric Wittman, the general manager of Atlassian’s developer tools, noted that Bitbucket’s customer growth the year before was around 80%, and that 1 in 3 Fortune 500 companies used Bitbucket. To align themselves with this kind of growth and present a cohesive brand, Atlassian combined all of their Git-based services under the Bitbucket brand, and added features that supported larger distributed teams and projects.

Over these years, Atlassian filled a gap in team SaaS tools by providing a broad vision for how teams could collaborate. While a lot of companies make acquisitions, most don’t execute well on integration. Combining two separate companies can be a nightmare, with clashing brands, personalities, and even code bases. Atlassian not only developed the skill of making smart acquisitions—they’ve also mastered the treacherous integration process from people to code.

This strategy was all about lock-in. With such tightly integrated solutions, the product superiority of one tool wasn’t necessarily the selling point. Instead, it was the comprehensive function of the whole suite of products. It didn’t matter if a company preferred Github’s functions to Bitbucket’s—if a team was already hooked into Jira and Confluence, they were going to use Bitbucket because it made their workflow more convenient and efficient.

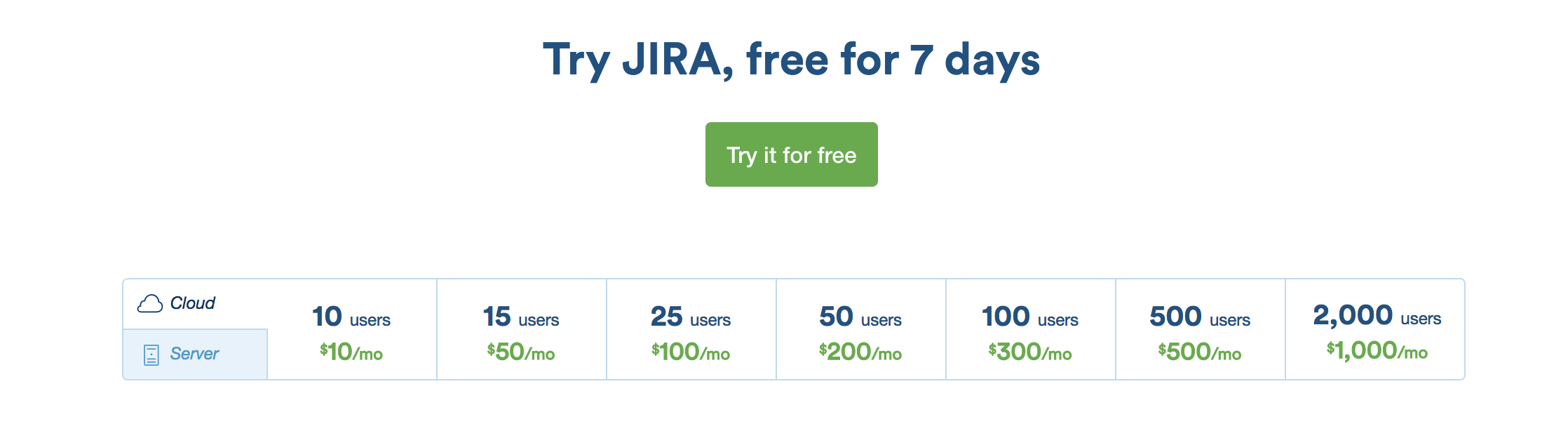

This strategy fed directly into Atlassian’s low-cost distribution model. They charged very little for the initial products and sold a low number of seats. Each product had its own pricing model, so teams could add products a la carte. Most of them started with a free trial.

Pretty soon their flywheel would kick into effect as more team members were onboarded, more teams and users got pulled in, and teams realized that trying to work without the Atlassian tools would be difficult.

The goal was for the sum of the parts to create a sticky, all-consuming whole. And in terms of acquisition efficiency, it worked. Atlassian spent between 12 and 21% of their yearly revenue on CAC from 2012-2015, compared to the SaaS industry median of 50-100%.

Adding products helped Atlassian finding new ways to hook users into the Jira suite—like with Bitbucket for developers and Hipchat for non-developer teams. This led to steep user and revenue growth.

The first few Atlassian products, like Jira and Confluence, brought in revenue at a steady trickle. The acquisitions allowed Atlassian to compound growth with each additional product. Right before Atlassian’s IPO, they announced $320 million in annual sales, which was up 60% from the year before.

Atlassian nailed their distribution flywheel and acquisition/integration machine. They were primed to widen the top of their funnel and try to win over even more teams in enterprise organizations.

2015-Present: Expanding to competitive and lucrative markets

To a lot of SaaS companies, Atlassian looks like the “end goal.” They’ve grown into a giant, public, global company with a complex and integrated suite of products for many different verticals.

But Atlassian understands that success is a continuum. They’re burning brightly, but unless they can keep up their growth going and maintain a stronghold over their markets, they’ll flare out. The goal is no longer to just build out a best-in-class suite of tools for developer teams. Rather, it’s getting an entire company—and all of the teams within it—using relevant products in the Atlassian suite.

While Atlassian works to offer products to many different teams within an organization, the company still needs to find a way to stay relevant to small teams. Many of their moneymaking products are getting unnecessarily complex for small teams. Instead of wasting time building lightweight versions, they’re using their successful acquisition and integration strategy to add lightweight products to the Atlassian suite.

Let’s take a closer look at exactly how their acquisitions and integrations over the past few years have helped them widen their funnel and expand into more lucrative and competitive markets.

2015: Atlassian held its IPO in December and started trading shares with a market cap of nearly $5.8 billion.

The company’s plan after their IPO was to continue expanding sales aggressively by investing in research and development. At the time, they invested over 40% of their revenue into R&D and wanted to keep up their 30% YoY growth for the suite of products. This in turn drove more revenue, which they could put back into R&D and acquisitions to continue fueling their flywheel.

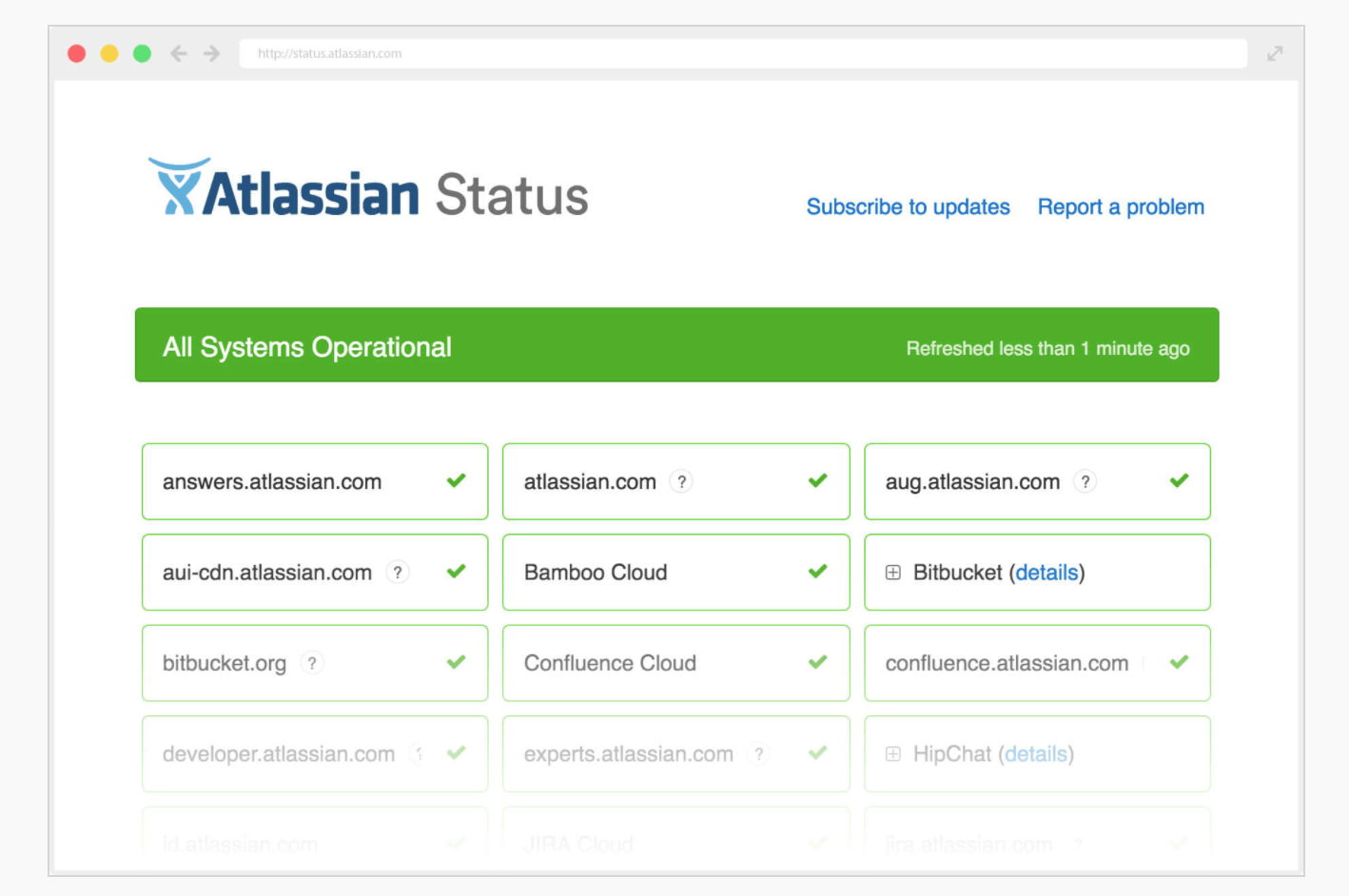

2016: To build itself out into an even more ubiquitous tool provider and help companies maintain their software, Atlassian acquired Statuspage, which allows businesses to keep users updated about the status of their online services. Atlassian already had a relationship with Statuspage because they were an early user of Hipchat, and because they already hosted their own statuses with Statuspage.

Atlassian’s president, Jay Simons, said that he thought the product filled a natural need within Atlassian’s offerings, especially alongside Jira’s issue-tracking services. It was a complementary product for users already using Jira and other products within the suite—but it was also a way to attract different users with a more broad use-case.

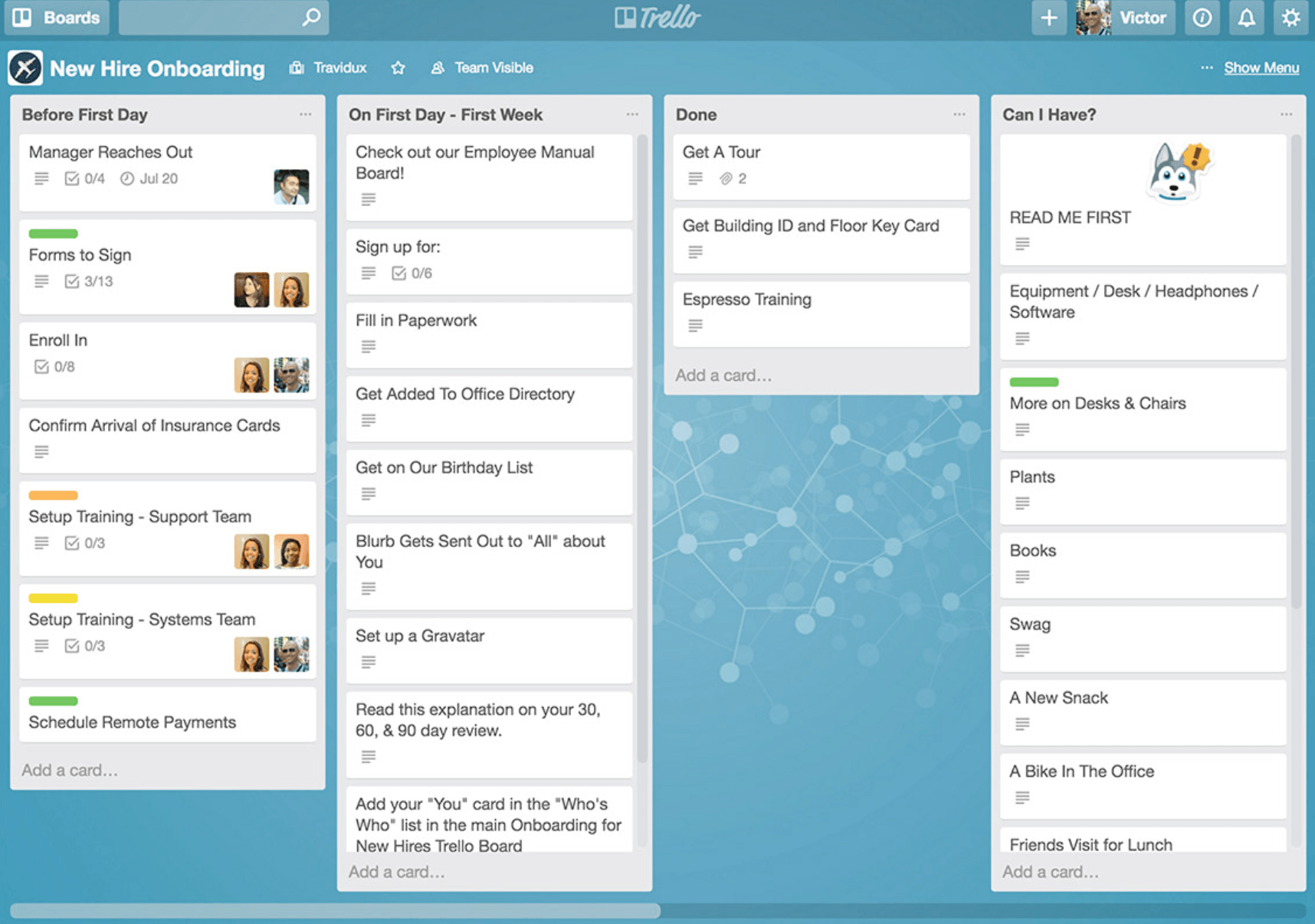

2017: Recently, Atlassian took a big step to target smaller teams by acquiring the lightweight project management tool Trello. I’ve already talked about Atlassian’s acquisition of Trello from the perspective of Trello’s potential—but the acquisition is also a really important recent step in Atlassian’s journey. Trello is a much simpler project management tool than Jira, and the simple Kanban board covers much broader use cases.

Atlassian needed a simple product that could fill the small-company gap in their distribution strategy as Jira moved upmarket and got more complex.

Trello is use-case agnostic, and is a good simple alternative to developer-specific Jira. The addition of Trello directly widens the funnel through which Atlassian can pull new, broader bases of users into their suite—and then cross-sell and upsell them to different products as their needs grow.

Later in the year, Atlassian made another huge product move by pivoting Hipchat’s services into an Atlassian-branded product called Stride. It’s a Slack competitor for team-wide messaging, which means it has some predictable features like text-based messaging and video and audio conferencing. It also has some unique additions like Focus Mode, an “away” setting while you’re at work, and Actions and Decisions, which show highlights from conversations that happened when you were away. According to Atlassian, the goal is to make teams more productive in ways that competitive products don’t do.

Atlassian’s recent product decisions, specifically around Trello and Stride, show that they are still finding new ways to target different teams within companies of all sizes. Both Trello and Stride are freemium products—this was Trello’s Achilles heel, but the free plans will be key for acquiring smaller teams that can’t afford to pay for enterprise products with enterprise functionality.

None of Atlassian’s most recent product acquisitions—Trello, Stride, or Statuspage—have market-specific use cases. They’re all springboards into virtually any team within an organization of any size. And they all have potential for horizontal adoption across teams once there’s buy-in with one.

These recent moves show that Atlassian is being very smart about growing product offerings for more wide-spread use cases in more competitive and lucrative markets. They’re turning acquisitions into additional product offerings—but at the same time, they’re clearing out potential disruptors and protecting the lock-in they’ve already established.

Where Atlassian can go from here

Atlassian’s pattern of acquisition—and their success with product additions—is very atypical. Looking forward, they have all of the pieces in place to continue edging out into even more additional markets through acquisitions.

With its acquisition/integration machine in place, here are some specific ways Atlassian can expand:

- Use Trello to land in new companies: The acquisition of Trello is all about finding a way to land in new areas within organizations. One of the biggest opportunities for Atlassian with Trello is to gain support among product managers on teams that aren’t yet using Jira or other Atlassian tools. Because Trello is so simple, there is much less friction, making it easier for teams to adopt the product. But it has a lot of powerful integrations with Atlassian tools that simplify workflows across teams. This adds another point of entry for teams into the Atlassian suite. If Atlassian can onboard PMs to Trello, they may be able to get those they collaborate with, like dev teams, using Trello as well. Exposure to Trello will make these dev teams aware of integrated products like Jira, and may motivate them to use the more developer-specific tools if they aren’t already.

- Use Stride to connect all elements of team collaboration: Messenger tools are important layers in any company’s ability to collaborate—and they have the potential to reach every single team in a company. Atlassian knows that it can’t give away this precious and far-reaching potential to Slack, which has integrations that allow users to plug in workplace tools. Stride is a defensive move, but it has potential to be really useful to Atlassian users and pull more users throughout a company into the Atlassian suite. Less back and forth and manual transfer of information would make work much more productive and painless, so Atlassian has to make sure their integrations and marketing around Stride tap into that.

- Build out designer tools: Atlassian provides users with Atlaskit, which is the company’s official UI library. It contains all of the tools needed to build in Atlassian’s design style. But Atlassian can expand to build out more agnostic front-end developer tools that can be used for UI design and UX testing. They have the potential to compete with Invision and build a better integrated tool for designers. They could kickstart the effort by purchasing a full stack UX design platform like UXPin.

The Atlassian team bought themselves a lot of time to make careful decisions by building a healthy business that could stand on its own legs, become profitable, and go public. Moving forward, if they continue to make calculated decisions, they could be the main provider of the most helpful workplace tools for SaaS companies of all sizes.

3 key lessons from Atlassian’s growth

The co-founders know that Atlassian is different than other SaaS companies. A lot of their decisions have been unconventional and really specific to their constraints. They’ve said to other companies, don’t try to copy us.

The bigger point for those growing their own businesses is that you shouldn’t and can’t copy any of Atlassian’s decisions because each company has to find ways to succeed based on their specific goals and challenges. But you can learn from the way that Atlassian approached their problems and how they looked for opportunities. These skills are vital to success and growth—without them, you’re dead in the water.

These are the key lessons that anyone building a company should take away from Atlassian:

1. Focus on capital efficiency early on

Many SaaS companies try to bootstrap their way to profitability. What made Atlassian’s journey so unique—and so successful—is that they pioneered a lot of unprecedented ways of doing this.

For one, Atlassian used a freemium distribution model starting in 2002 because they couldn’t afford a sales team. There weren’t a lot of enterprise software companies doing this at the time. But this made sales and marketing spend from the outset very low.

Another important step towards capital efficiency was aggressively adding more products very early on. This was risky because many companies gain their footing by focusing on a single product. Atlassian started building out a suite very early, which bolstered revenue.

There are two main mechanics that contribute to better capital efficiency: lower CAC and higher revenue. Atlassian found specific ways to lower their CAC and grow their revenue that worked for them, and you can do the same by looking at your unique constraints and considering the following:

- You can lower CAC by targeting more effective marketing channels, onboarding freemium users more effectively to paid accounts, and focusing on inbound marketing through content and free trials.

- You can grow revenue by increasing your prices, adding additional revenue streams from new products, and cross-selling users to other products and add-ons.

Capital efficiency was vital to Atlassian’s early growth and success, and it’s a good mentality and practice for any SaaS company.

2. Own a particular customer segment

Atlassian put down roots in developer teams. From there, it had a point of entry within enterprise organizations to expand to other teams. Having a stronghold over developer teams who loved using Jira and wouldn’t want to switch was essential to onboarding other teams to auxiliary Atlassian tools.

Salesforce has done the same thing in the sales market. Even though they’re now expanding out into almost every market in enterprise businesses, they started with just a CRM and got lock-in within sales teams. Winning over one department is key to playing the long game.

When you’re just starting out, it’s hard to win over broad use cases because it’s difficult to hone in on one specific value proposition and get anyone’s attention. Instead, focus on one department within an organization and evangelize your product to that specific group of people. There are some specific steps you can take to grow this evangelism:

- Offer workshops and networking conferences with early groups of users in one specific market

- Talk to early customers within your target market about what specific problems your product solves, and make sure that your marketing reflects these pain points and solutions

- When you start building add-ons and new features, make sure they’re specifically related to your target market before expanding out to other segments.

3. Choose the style of business you want to master

There are many ways to build a great company. Some choose to focus more on product innovation. Others, like Atlassian, put more emphasis on strategic acquisitions. A company like Salesforce chose to focus on delivery method and industry disruption. Some, like Basecamp, focus on single product simplicity.

There’s no one-size-fits-all path, but there is a common theme among all of these successful companies. They all developed a concept to master early on, and they stuck with it and followed through in all of their decisions.

Deciding what is more important for your company to master early on is challenging but it gives you sharp focus. Two important factors will shape this early decision:

- What is your initial vision for your company and product?

- What do you want to accomplish with your company in 5, 10, and 20 years?

Buck convention and build your own growth engine

Building a long-term company is challenging because you’re going to face so many different constraints at different points in your business. The same factors won’t necessarily drive your growth at every stage. But if you know how you want to grow and have a strategy around what steps you’ll take to do it, you can develop a framework for making decisions in many different circumstances.

Atlassian’s strategy—acquisition, integration, and organic distribution—was particularly special because not many other companies have done it (and done it well). Your’s may look different from other companies, too. The goal is to develop a framework that helps you win with the cards you’re dealt.