Asana’s Rise to a $1.5 Billion Valuation

“Every team in the world is capable of accomplishing bigger goals… software could help empower them to drive work forward with more ease, clarity, and accountability.” – Asana co-founders

There are a handful of common workplace struggles that plague almost every industry. Emails pile up. Status meetings are unproductive. Teammates working on the same project don’t have access to the same information. Day in and day out, these inconveniences can become overwhelming and create “work about work.”

Two engineers at Facebook were sick of dealing with it, so they cobbled together a side project to make their workflow easier—which turned out to be the seedling idea for a $1.5 billion company.

When these Facebook engineers split their side project out into its own company—Asana—they had a single driving purpose. They wanted to kill email at work. But in the process, they found that there were many ways they could make collaboration and communication more efficient. Better project management and collaboration was something almost every team, in every industry, could benefit from.

So the Asana team did something really difficult—they created a tool that anyone at any company could use and would want to use.

They did this by focusing on two main things:

- They were really intentional about managing the scope of the product exclusively around project management.

- They were committed to figuring out how to make the best project management tool for a very broad user base.

By reimagining communication in the workplace and linking together email, data, and project updates, Asana helps companies build a “team brain” that enables them work better, smarter, and more cohesively. Today, the company has over 20,000 paying customers including Airbnb and Uber, as well as hundreds of thousands of free users.

Let’s take a closer look at how Asana took a lofty idea and built out a SaaS tool that serves everyone—from freemium freelance users to corporate enterprise teams. We’ll look at:

- How early on, during their private beta, Asana clearly defined their product to differentiate it from other collaboration software

- How Asana iterated and did extensive user testing to find out what would resonate with their wide audience

- How Asana doubled down on creating a great user experience, starting with a ground-up redesign

The Asana team didn’t necessarily build a perfect product, but they had a strong product vision and made smart adjustments along the way. These long-terms strategies are valuable to anyone growing a company—so let’s dive in.

2008-2011: Asana’s private beta and differentiation from other collaboration tools

“Our goal is that, much in the spirit of something like e-mail, this will be useful to all people.” – Dustin Moskovitz

Asana—the tool and the company—were both built with intention. The first two things the Asana co-founders created when they formed the company in 2008 were the product codebase and a list of the company values. They didn’t just want to build an app—they wanted to build a new way of doing work.

This is because they’d experienced the old way of doing work and they were tired of it. The Asana co-founders, Dustin Moskovitz and Justin Rosenstein, were seasoned Silicon Valley veterans. They’d worked for some of the biggest tech players in the game—Facebook and Google—and they knew the Achilles heel of these giants: poor organization and information overload.

Rosenstein said, “When I ask people how much time they spend not doing their job—time spent on ‘work-about-work’ or phone calls or e-mails—people regularly tell me 60, or even 90 percent.” In 2008, the two started working on a side project at Facebook specifically to consolidate information and increase transparency.

But their simple project management tool became much more popular on the Facebook team than they’d expected—a pattern that looked familiar to Moskovitz and Rosenstein.

“Every time you walked through the office, you would see people interacting with this system on three out of four monitors; this reminded me a lot of the early days of the Facebook product, when walking through a campus computer lab meant seeing it up on all the displays.” – Dustin Moskovitz, co-founder

Seeing such a strong indication of product-market fit—even if in a really small sample market—confirmed to Moskovitz and Rosenstein that they were addressing a big and universal workplace issue. They believed this so strongly that they started to formulate a lofty mission for their project management tool: “To help humanity thrive by enabling all teams to work together effortlessly.”

They wanted to dedicate the time and attention it would take to create a tool that would really make a difference for people—and they started to feel like their product’s mission didn’t fit in at Facebook. So they left the social media giant, and formed a new company around their project management tool. They called it Asana, and never looked back.

2008: In December 2008, Justin Rosenstein and Dustin Moskovitz left Facebook to start working on Asana. Moskovitz was the co-founder and first CTO of Facebook, and Rosenstein was the engineering lead. At Facebook, Rosenstein and Moskovitz had gotten personally fed up with the amount of redundant and inefficient task management work they saw their team doing. As team and company leaders, they invested the time to help their company run better by developing an internal team project management tool called Tasks. They didn’t know it at the time, but this internal tool would soon become the initial prototype for Asana.

Tasks was quickly adopted by teams across Facebook, and that’s when the co-founders realized that their side project had teeth. Moskovitz handed off all of his other responsibilities to focus entirely on Tasks, but even then he couldn’t keep up with all of the ways the Facebook team wanted to use the tool. Moskovitz started to feel like his mission for the internal tool didn’t fit in at Facebook. The tool’s objective to increase efficiency at work didn’t fall under the umbrella of Facebook’s mission to build community and bring people closer together. When he decided to split off from co-founder Zuckerberg and the rest of the Facebook team, he said it was “one of the hardest things he’s ever had to do.” Zuckerberg was supportive of Moskovitz and Rosenstein when they decided to form Asana as a separate company.

2009: The following year, Asana raised $1.2 million in an angel round from 14 investors, including Peter Thiel, Sean Parker, and Marc Andreessen. This was essential for getting early visibility in Silicon Valley. Both Moskovitz and Rosenstein had a huge combined network of VCs and company leaders who they could rally behind their product.

The same year, Asana raised a $9 million Series A from Benchmark Capital and Andreessen Horowitz. Investors like Matt Cohler, a partner at Benchmark, were very excited about the product, even if they were vague about it—when asked why he wanted to invest he said, “huge market, totally new and compelling product.” Asana was less than a year old, with a team of only five people (including the co-founders), and they already had $10 million in funding.

According to Moskovitz and Rosenstein, the purpose of the funding was to hire world-class engineers and product designers and give them the best possible work environment. This included in-house yoga, organic home-cooked meals twice a day, and up to $10k for each person’s individual work setup. From the beginning, recruiting the best talent—and then treating them like they were the best—was top priority for the co-founders. Since their tool aimed to make the work easier and better for users, they wanted the company’s environment to reflect the same ethos for its employees.

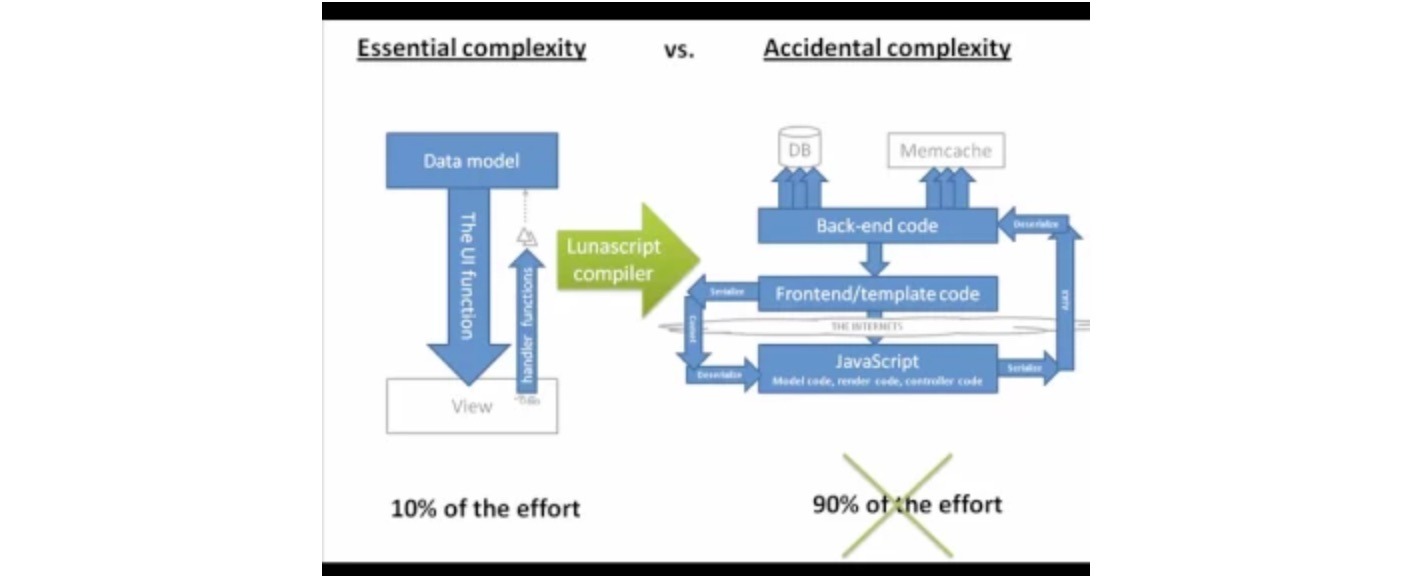

2010: This year, Asana gave the world a sneak-peak of their own in-house programming language, Lunascript. This was the unique language that allowed Asana to provide users with the dynamism and efficiency of a single-page web-app at a time when this was very complex for most companies.

At the time, the team was working on a private beta, but they were running into a few issues. The vision they had for the product was a single-page web app, which had the tendency to run slow because it was so dynamic. On a single-page web app, all changes and keystrokes happen in real time on everyone’s computer. Not many companies were building apps like this in in 2010, so to support their forward-thinking project, they used their own language with the goal of reducing bugs and latency as much as possible. According to Moskovitz and Rosenstein, the framework slashes 90% of the time needed to code rich web apps and helps Asana to run faster.

The Asana team started talking about the product more publicly in 2010. At this point, they had 15 alpha users who used a simplified version of the product the internal Asana team was using. The company was very focused on getting early feedback from these users, who were mostly friends and small startup teams. Still, there was public interest from others who wanted to start using the product. Asana was generating a lot of buzz because the founders were so high-profile in the tech industry and they wrote publicly about their company and their tool. But the Asana team purposefully kept the user base small and the product in alpha for so long so they could focus on user feedback from a small group and crush problems early on.

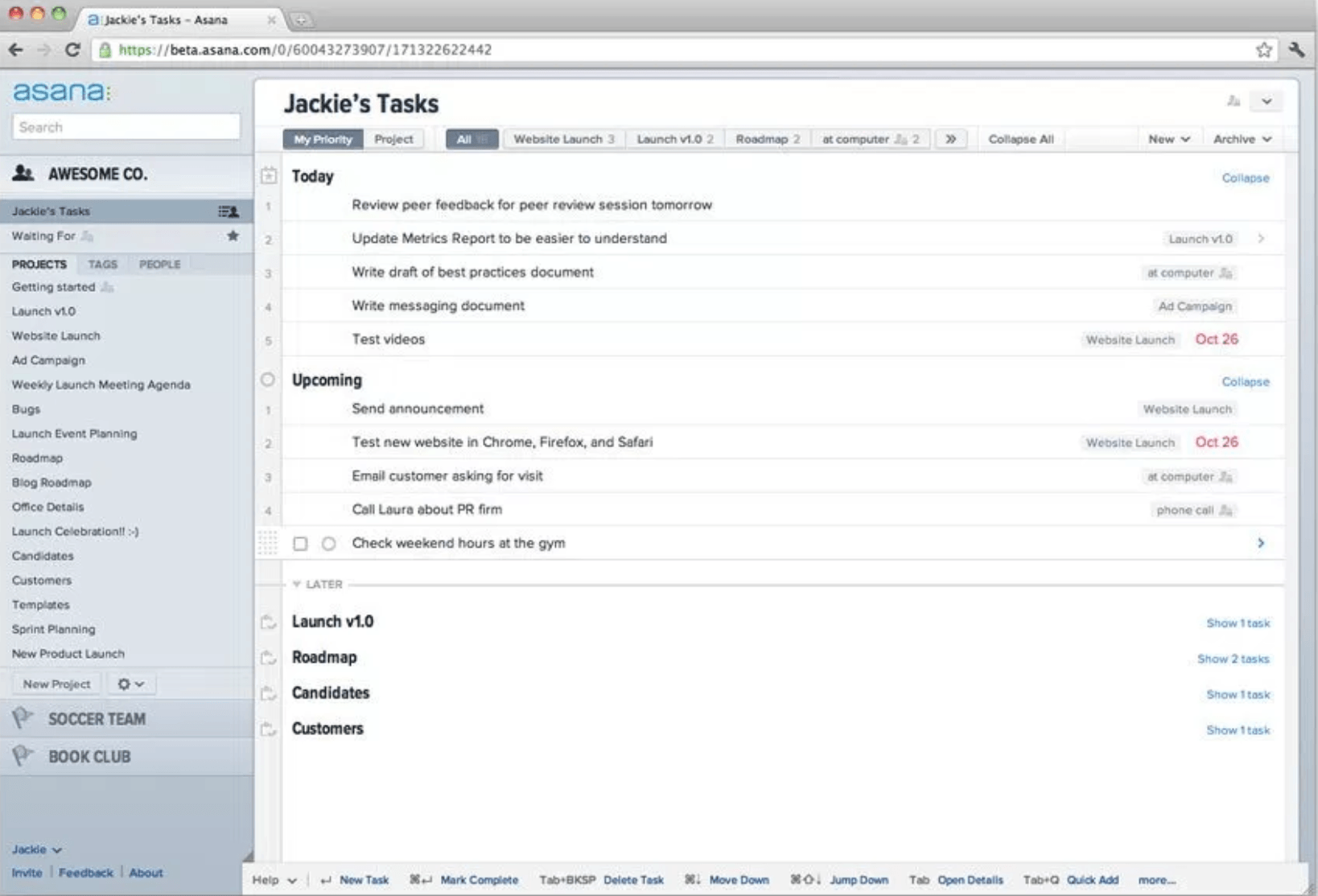

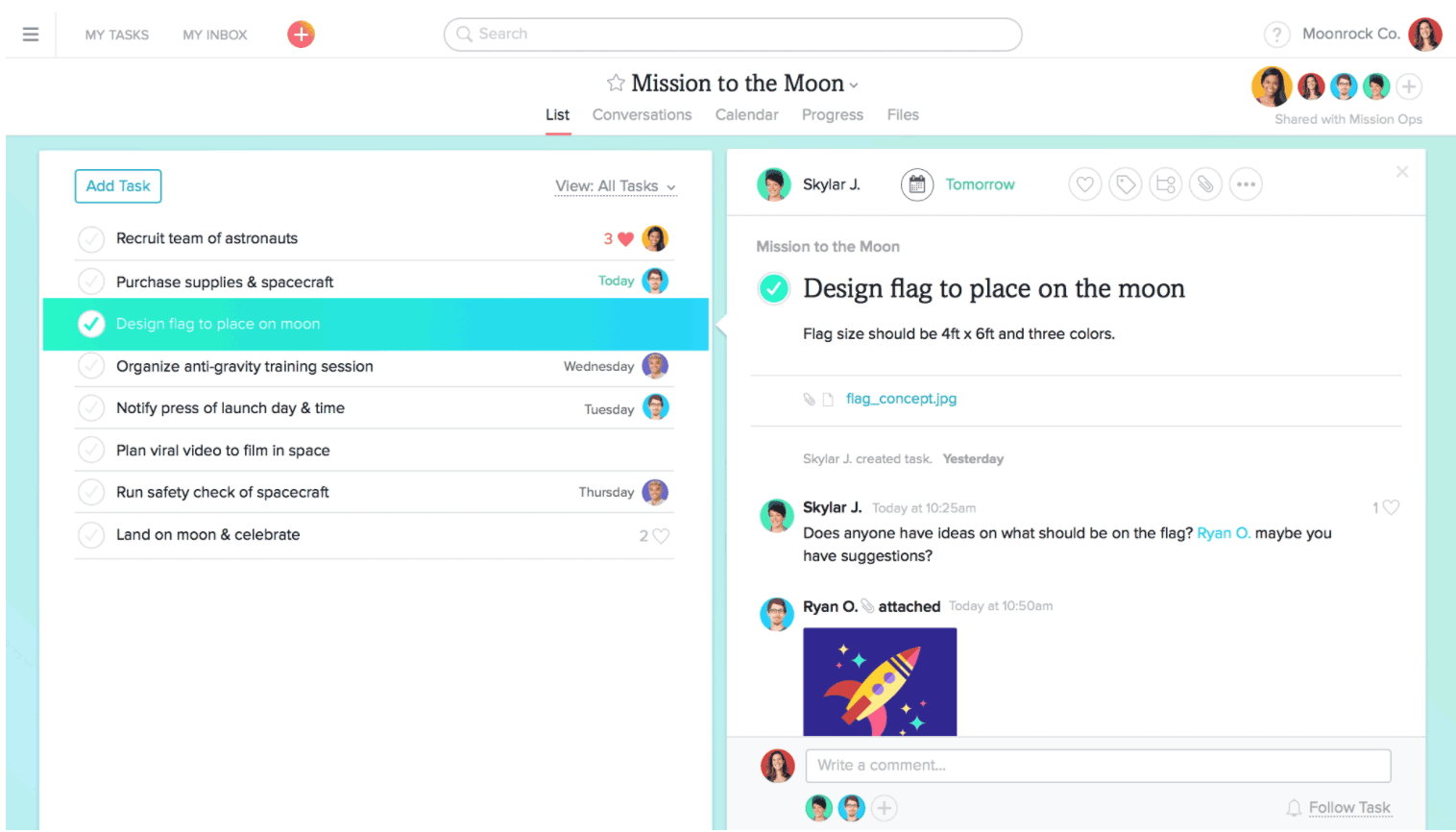

2011: Early in the year, there was a 1,200-company wait list to get into Asana’s beta. By November, they ended their private beta and launched to the public. The early version of the product allowed users to log projects, leave comments for co-workers, tag assignments, and attach relevant files and emails. It was a central interface for team organization and communication around projects.

For teams of up to 30 people, Asana offered their product for free—and companies could create more than one team on the platform. Keeping the product free at first was key for early adoption and growing usage within teams, especially in the competitive project management sphere where SaaS tools like Basecamp already existed.

In their first few years, the Asana team succeeded at creating the product they’d set out to build. They had something that united the communication and collaboration of email with the data repositories where projects and work actually take place. They’d also succeeded in taking their product out of the alpha stage and bringing it to market—and they experienced an enthusiastic initial response. Early users were happy and remarked about how fast the tool was.

As they released their tool to the public, the team was careful to define what the product was—and what it wasn’t. Even though chat features and social networks were blowing up at the time, Asana did not want to add those features. In late 2011, one reviewer wrote, “Asana doesn’t have any chat or status update features, and you won’t find your coworker’s employment history on it, either. It is not a social network. Instead, rather than building a network that revolves around people, Asana’s founders say they set out to build a network that puts your work items at the center.”

Once Asana had solidified its mission, defined its product, and launched to the public, the next step was to see what users actually thought about the product. Next, the team focused on making changes and asking for feedback. These were the unsexy but incredibly important steps that helped them realize their mission to build a product that made people’s lives better and work more efficient.

2011-2015: Iterations and user tests help to strike the right chord across a broad user base

“Asana feels like I’m working with a low-friction, smart piece of paper.” – Harrison Shoff, Design Engineer at Airbnb

Asana’s early users said that the product was one of the first product management tools that their teams actually liked to use. The proof was in the numbers—a year after public launch, over 75% of the teams that had joined Asana were still using it.

But great early reviews weren’t enough for Asana. They wanted to grow adoption to more teams and bigger teams, and wanted everyone to love their product. That meant seeking out the harsh feedback and learning from it.

Early demand had proved to Asana that they had a good idea for how to build a better team collaboration tool. But the truth was that most companies were still entrenched in their old workflows and still dependent on email. To make a product that people would deem necessary, the team had to add more functionality and make it fun to use. As a starting point, they began reimagining the design of the product, which at the time was utilitarian and “unsexy.”

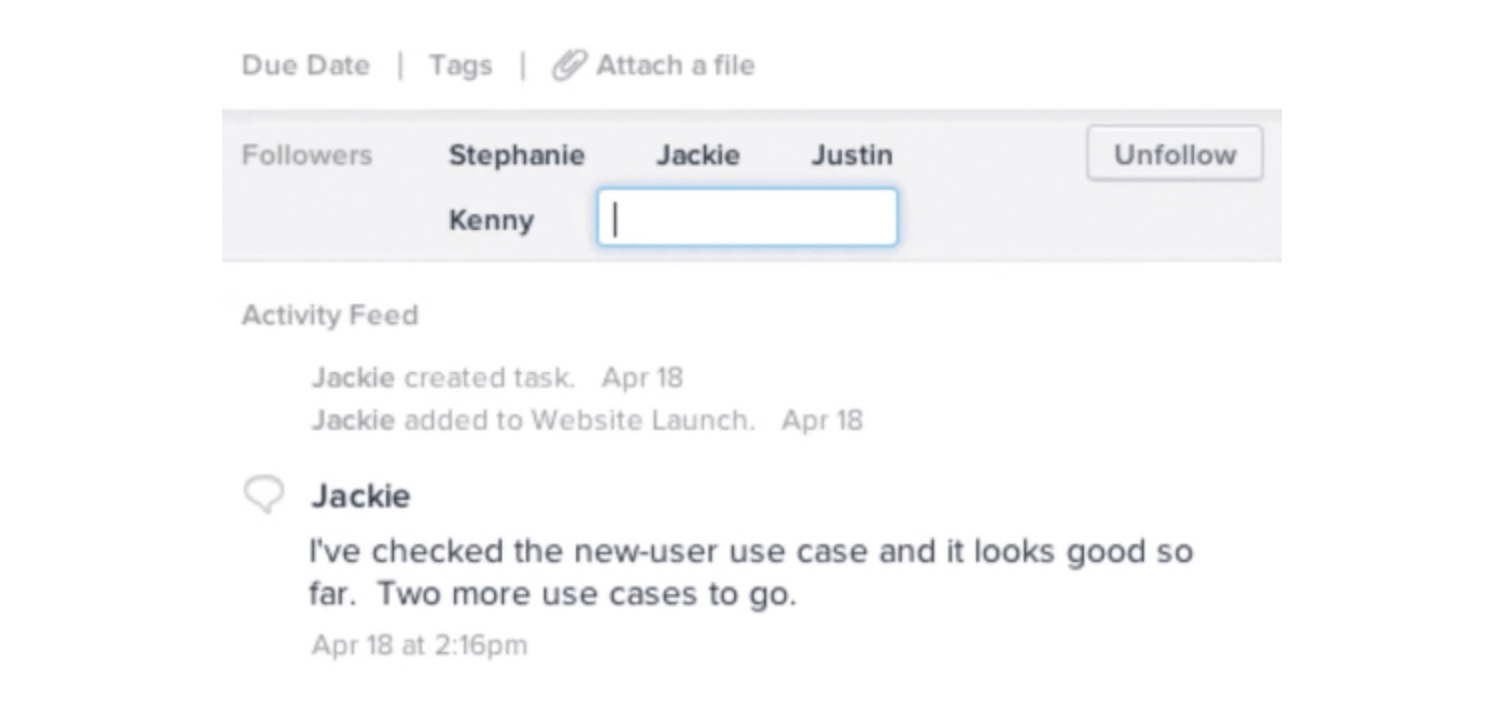

In their next stage of growth, Asana focused on iterating their pricing plans, building out a lot of new features, and tweaking their product design—all to see what would strike the right chord across a wide user base. They built a dedicated team for user research so that as they made these changes, they could really understand what was most helpful to users.

Let’s take a closer look at how these iterations and user tests helped Asana learn more about building a sticky product across a wide user base.

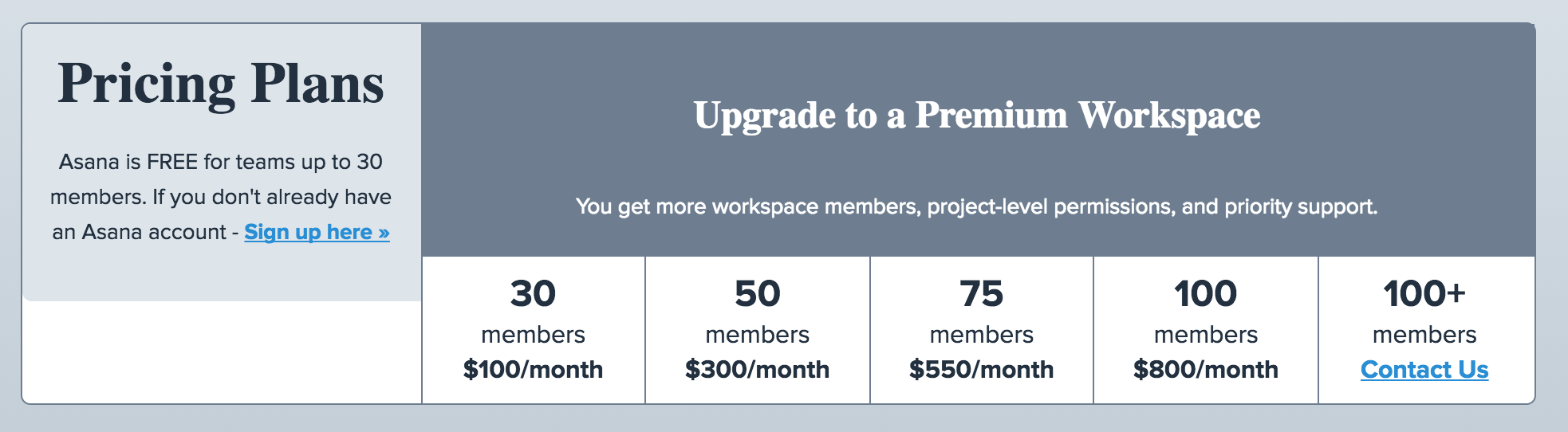

2012: In early 2012, Asana already had tens of thousands of teams signed up, including companies like Airbnb, Facebook, Twitter, and Foursquare. People had created over 10 million tasks and completed over 4 million of them, which demonstrated that the product actually helped people accomplish more at work. As users spread the word to more of their teammates, Asana saw a growing need to cater to teams bigger than 30 people. So in April, they launched their premium paid plan to accompany their regular free plan.

These started at $100/month for teams of 30 and had tiers for 50, 75, 100, or more members. This was Asana’s first step towards monetization—but more importantly, it was their first step towards viral grassroots adoption on large enterprise teams.

In April 2012, Asana also released their own API. This made the tool even more flexible for more teams by allowing people to build on top of it. Teams who needed specific functionality that Asana didn’t offer yet could start using the tool anyway and customize it to support their unique workflows.

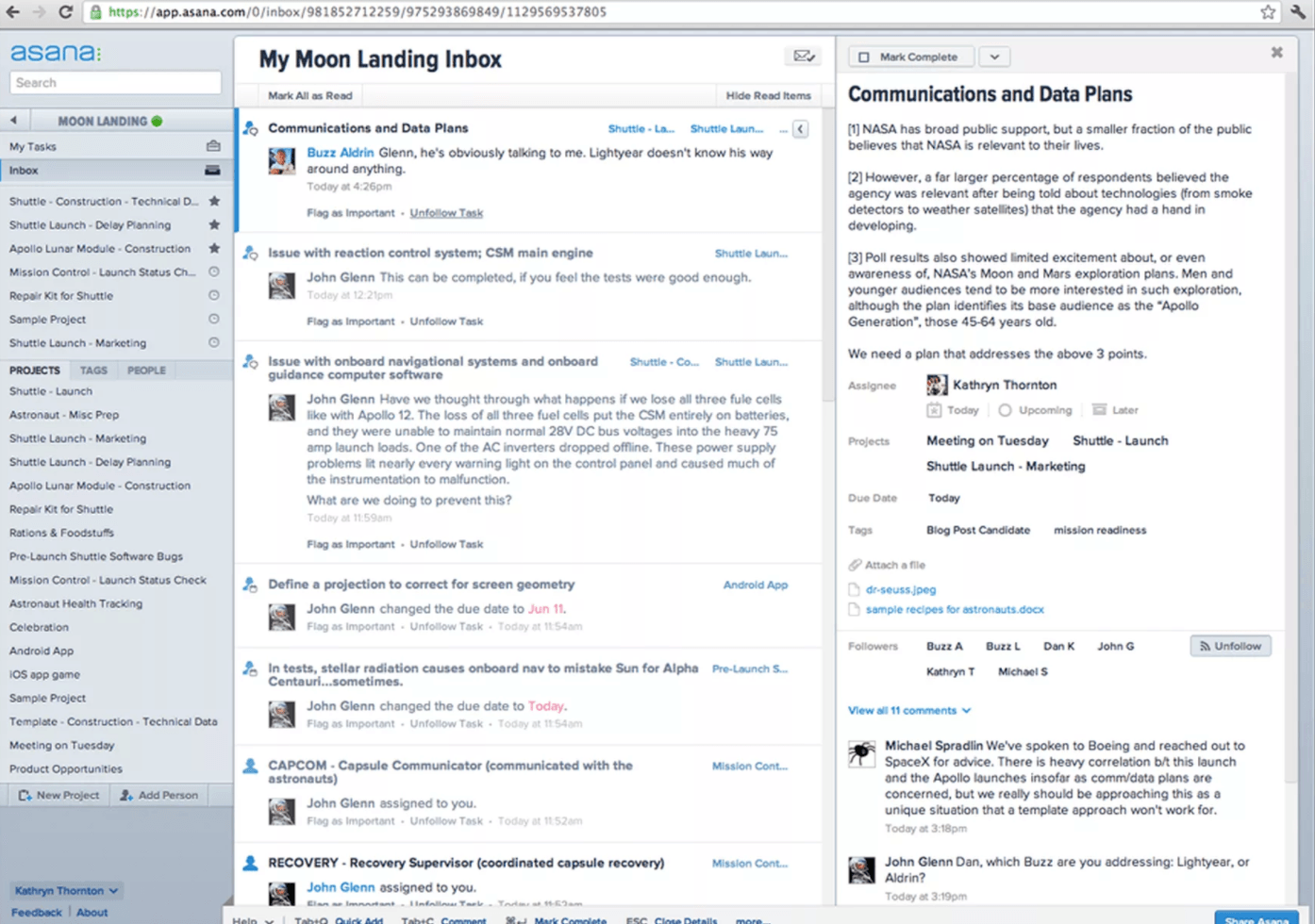

In the same year, Asana launched a feature that they’d been working toward since day one. They released their Inbox tool, meant to directly replace email. In its release notes, the co-founders talked about how email was a 40-year-old system designed to send electronic mail, and had no place as the main workplace communication system. It was isolated, didn’t provide enough context, and ultimately made teamwork less effective. Their solution, Inbox, was a feed that showed you relevant tasks, comments, due date changes, and project updates.

The tool made it really easy to unfollow threads and conversations so that you could keep your feed uncluttered and centered around exactly what was relevant to you. For the Asana team, it was essential that Inbox show all of the communications and information that users would normally send through email. “We could’ve just built an activity feed,” Rosenstein said, “but we wanted to build a holistic solution from the ground up that replaces what we do with email.”

Users were excited about the new feature—TechCrunch called it “the email slayer we’re all longing for”—but the Asana team still took this opportunity to collect more feedback. The most common feedback from users was that Inbox helped cut down on internal emails, but they still needed a better way to deal with external communications. Rosenstein promised that this was on Asana’s product roadmap.

Just nine months after their public launch, Asana was a 22-person team and everyone had the same job title—“Asana.” Tens of thousands of teams were using their product, hundreds of teams were upgrading to premium plans, and over 18 million tasks had been created. Hundreds of thousands of messages were being sent every day in the new Inbox tool.

This user traction helped Asana raise a $28 million Series B led by Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund, with investments from Benchmark Capital, Andreessen Horowitz, and Mitch Kapor. The deal valued Asana at $280 million. Rosenstein said he thought of the deal as “an exclamation mark on an incredible nine months.” This capital would fuel R&D for their extensive user research and upcoming product roadmap.

To fuel growth even further, Asana started running their first set of growth experiments. They tested many different components of the product, including: signup flow, notifications, mobile, performance, and UI. They meticulously noted user comments, goals hit, and goals missed for each of these experiments. In this feedback they found that one of Asana’s biggest shortcomings was the UI, which users said was too clunky.

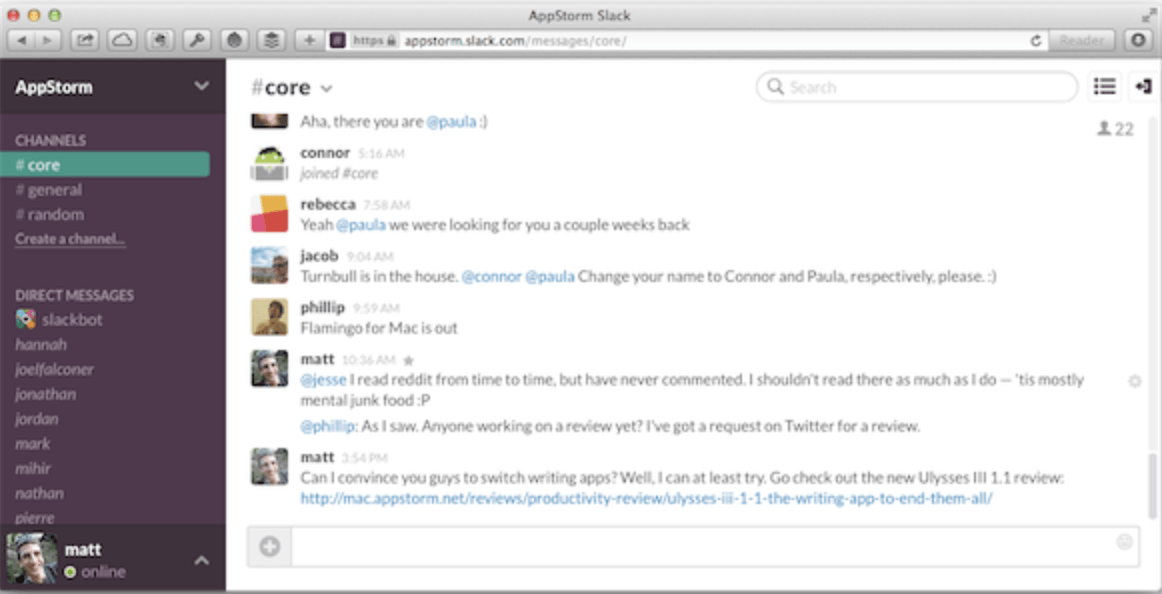

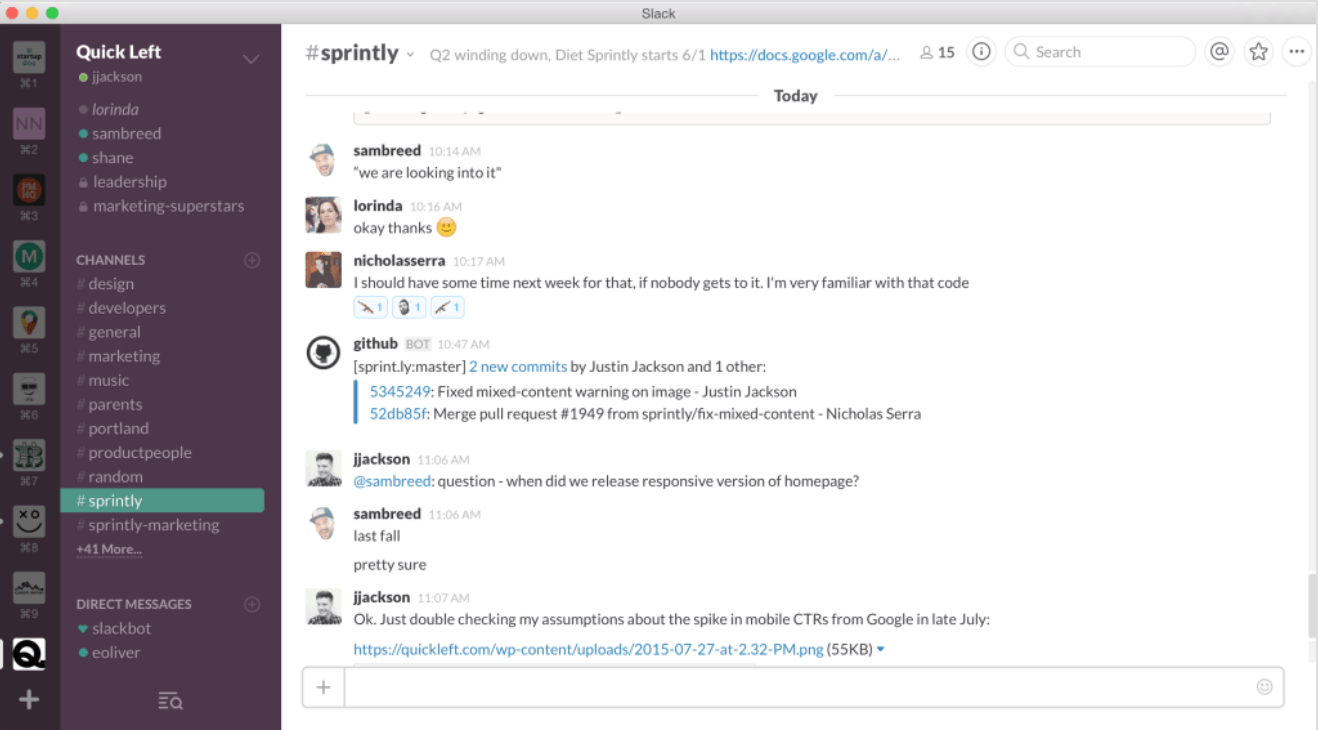

2013: Around this time, several next-generation workplace apps were born that emphasized Asana’s old-school, utilitarian design. One of the biggest was Slack, which had a fun and approachable UI that was described as “radically friendly.”

While Slack wasn’t a direct competitor for Asana, its early success set the tone for the changing way workplace apps were expected to look. Asana already knew from user feedback that they needed to work on the UI, so this was the push they needed to start redesigning the product.

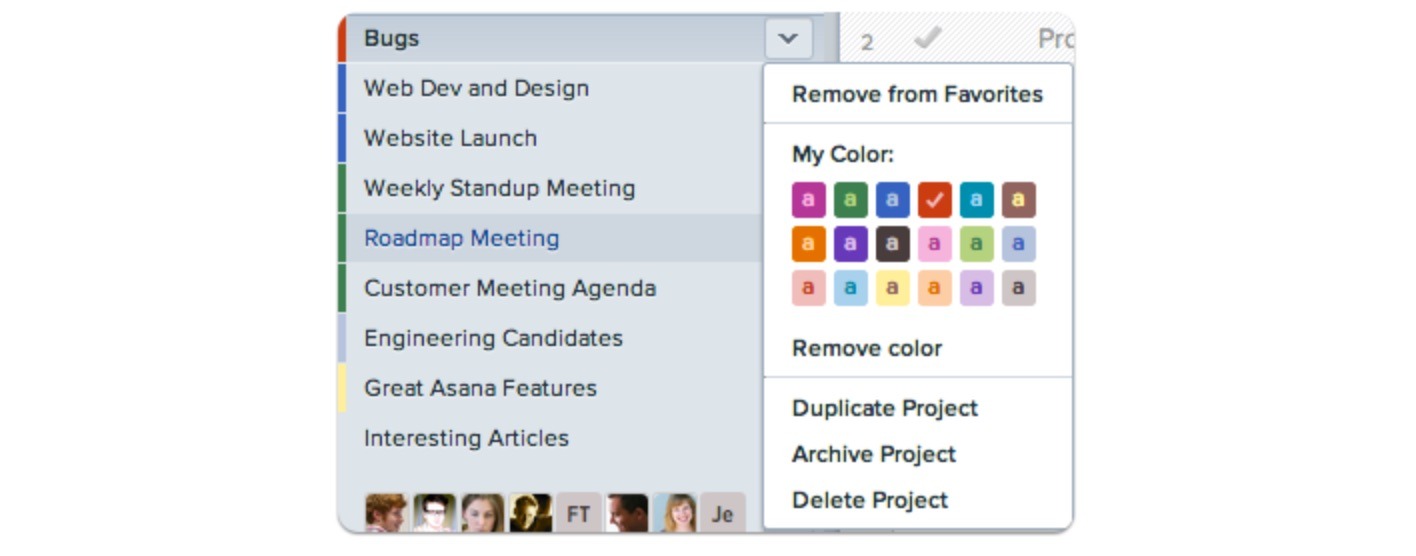

At first, they made small changes like adding colors to help people organize projects and tags.

This marked a shift from their old design philosophy: “[Asana’s] minimalist design philosophy is reflected in our color scheme: a range of unobtrusive grays and whites that are designed to be calming—to not catch your eye and distract you.” But when they realized more color was what users wanted, they began to incorporate it.

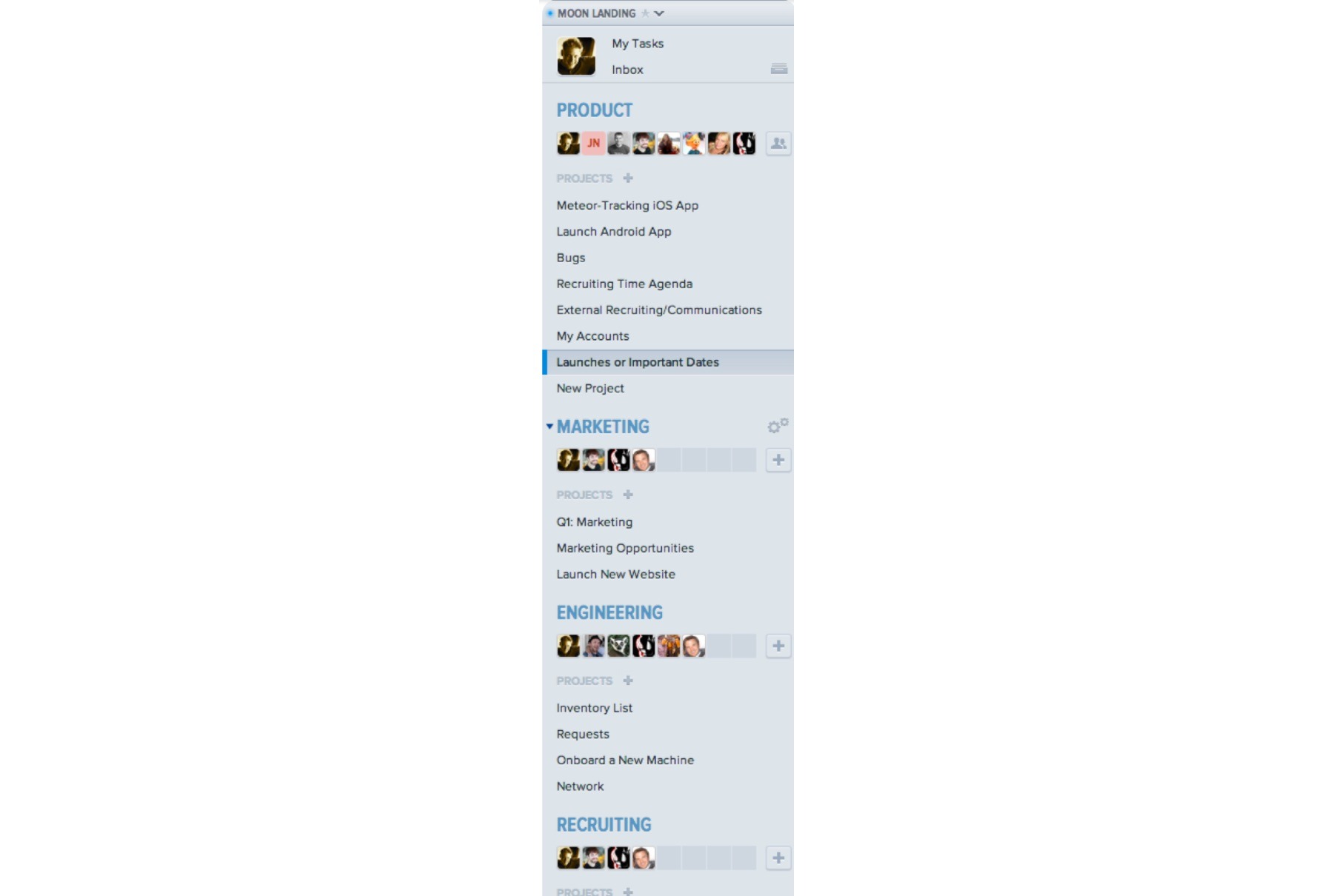

2013: As more teams upgraded to the premium plan, Asana realized these larger teams of 100 to 1,000 needed more support from the product. They added an Organizations feature, which made it easier for different internal teams within a large organization to work better together in Asana.

This feature gave big companies the ability to collaborate with multiple teams under one organization. Different internal teams could work with the same Tasks, Inbox, and Search. There was centralized administration across teams. On the other hand, the feature also made it possible to give the right level of access on different projects and information to each team. This new functionality provided the right about of flexibility and hierarchy that is really important to large, multifaceted organizations.

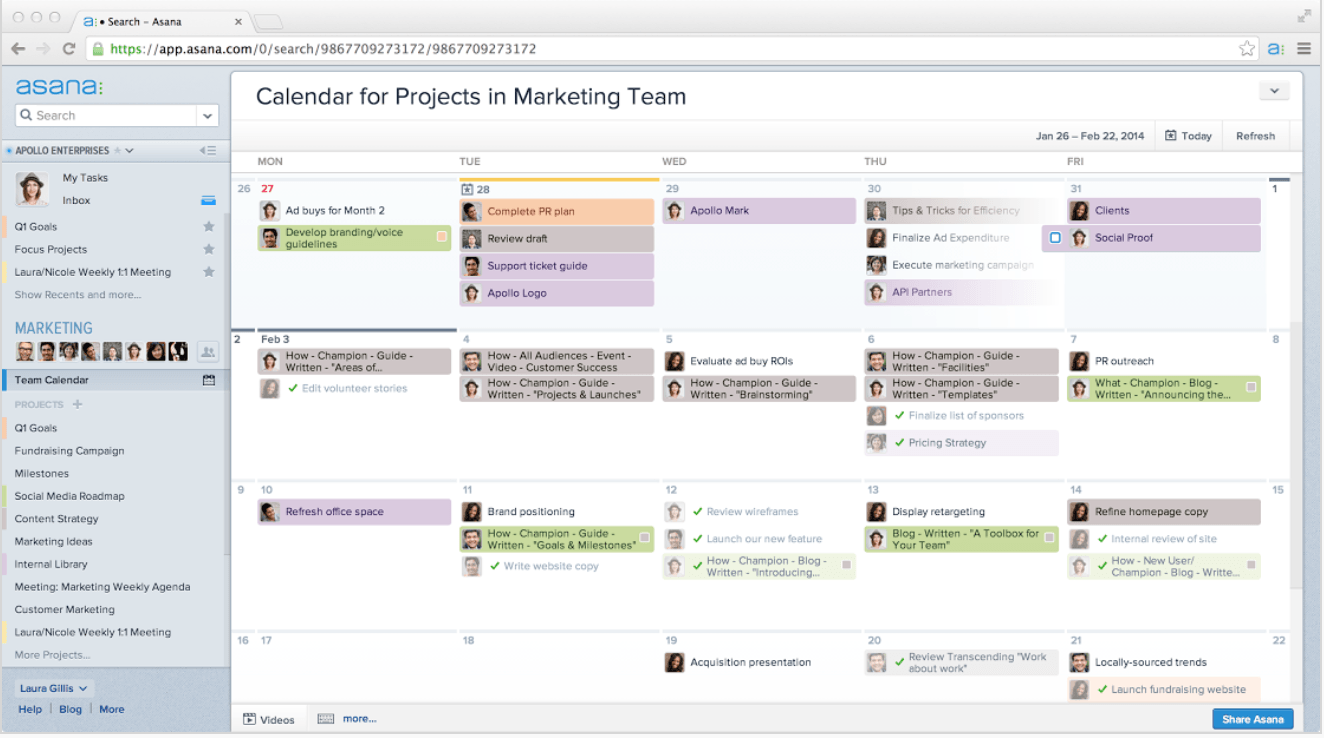

2014: Asana’s top-requested feature was a calendar function. The tool already helped teams organize and assign work on a granular level, but it lacked a way to show work mapped out visually over time. So Asana released Calendars in 2014, which provided users with a new level of visual organization.

The Calendar feature was especially useful because it was dynamic and sortable. Asana reported that this feature was their most popular feature to date, with people even throwing dance parties because they were so happy about the release.

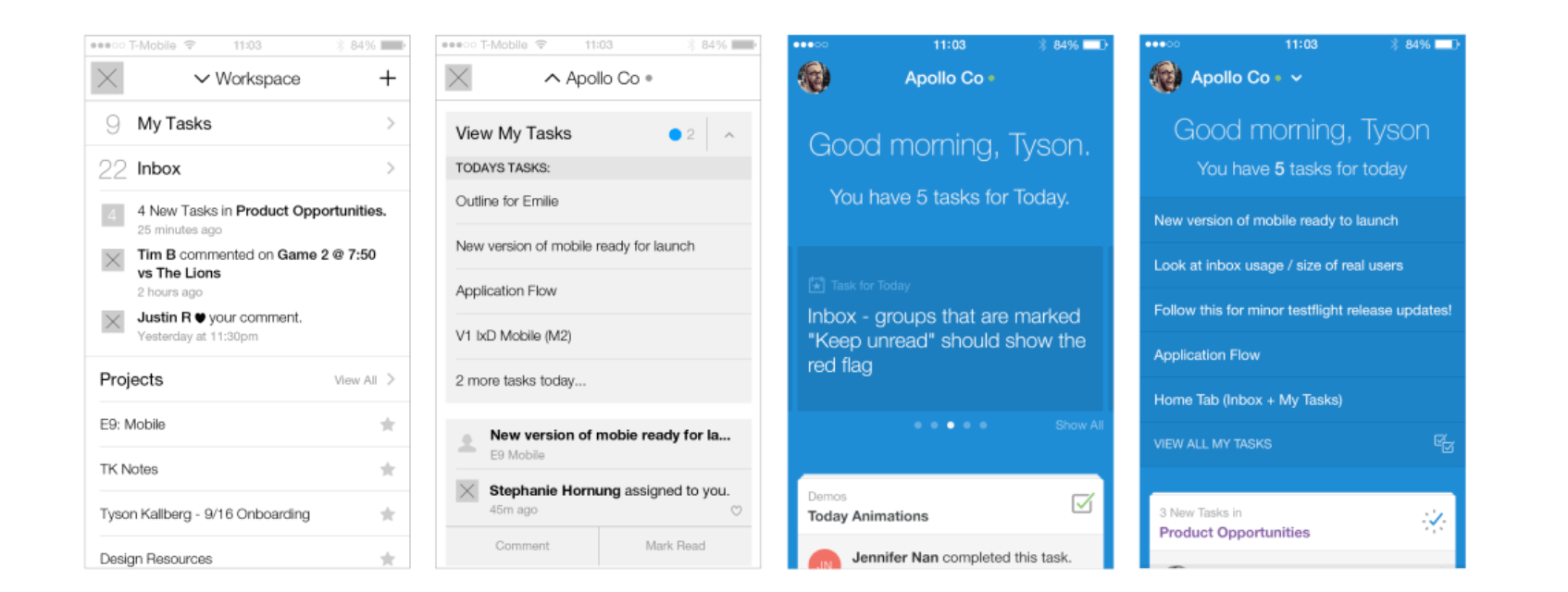

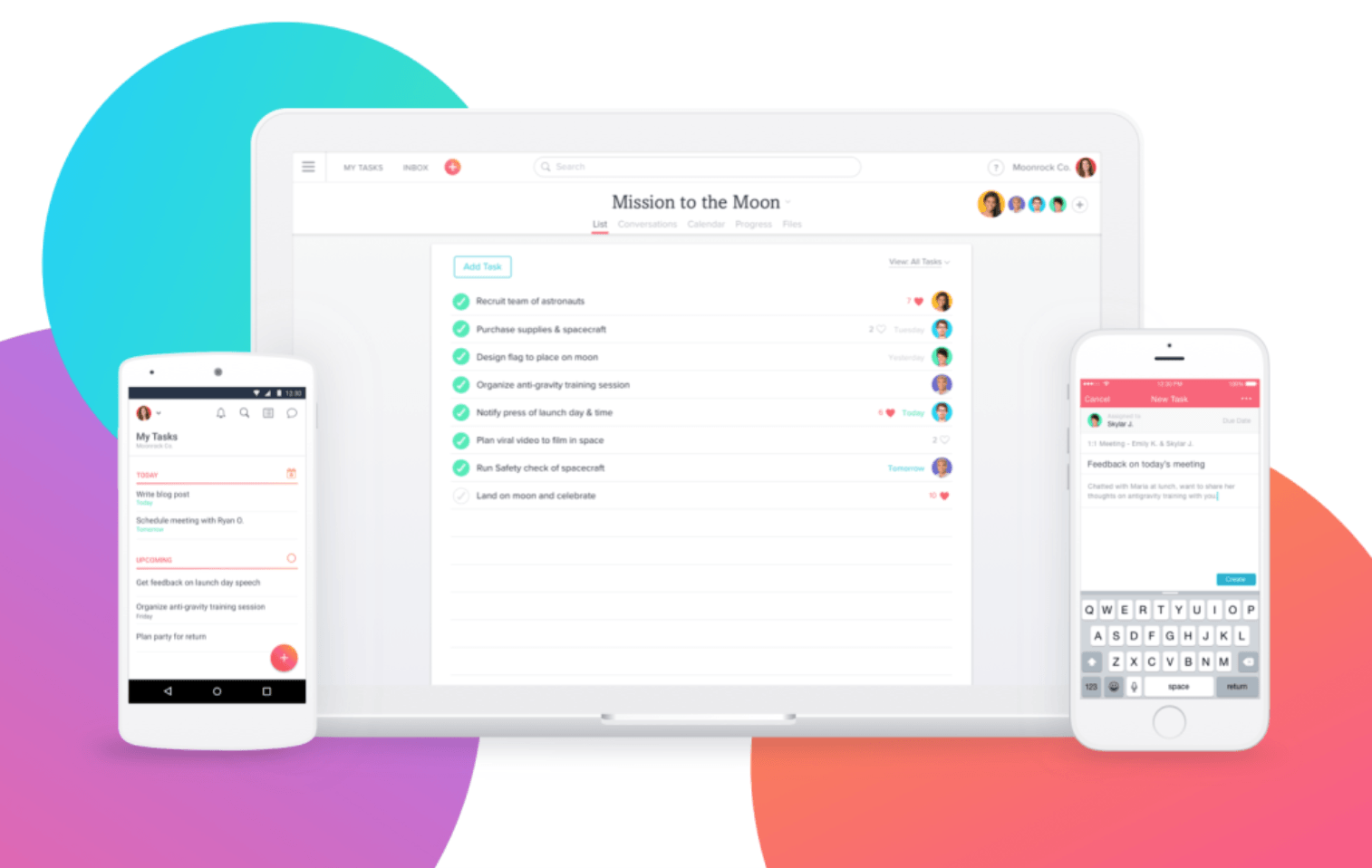

To continue learning more about how people were using the app and what users really wanted, Asana created a user research team. The number one research takeaway was that users wanted a better mobile experience. So in July, the team released an entirely new iOS app from the ground up, with plans to roll out the new design to Android and the web app soon after.

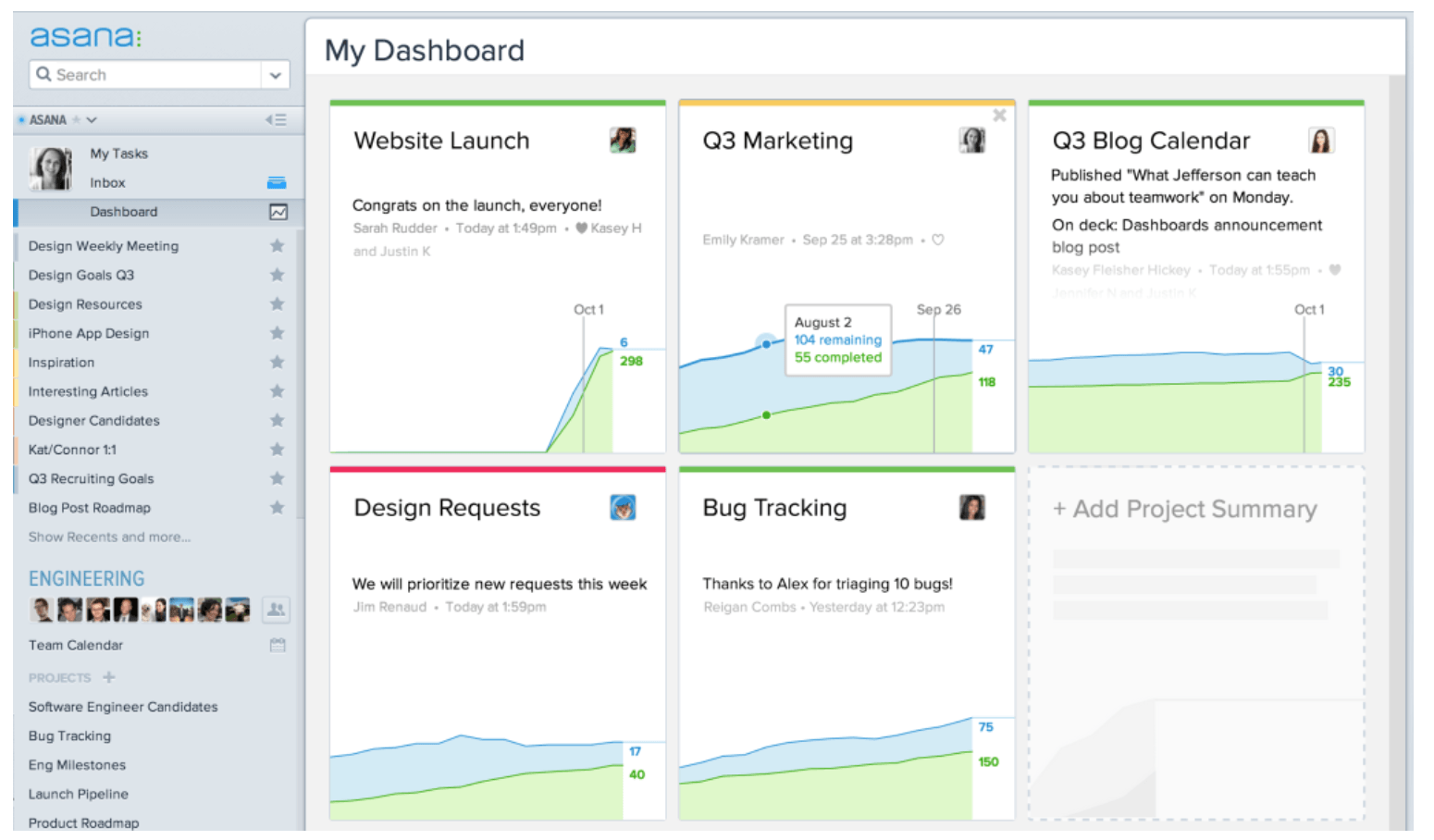

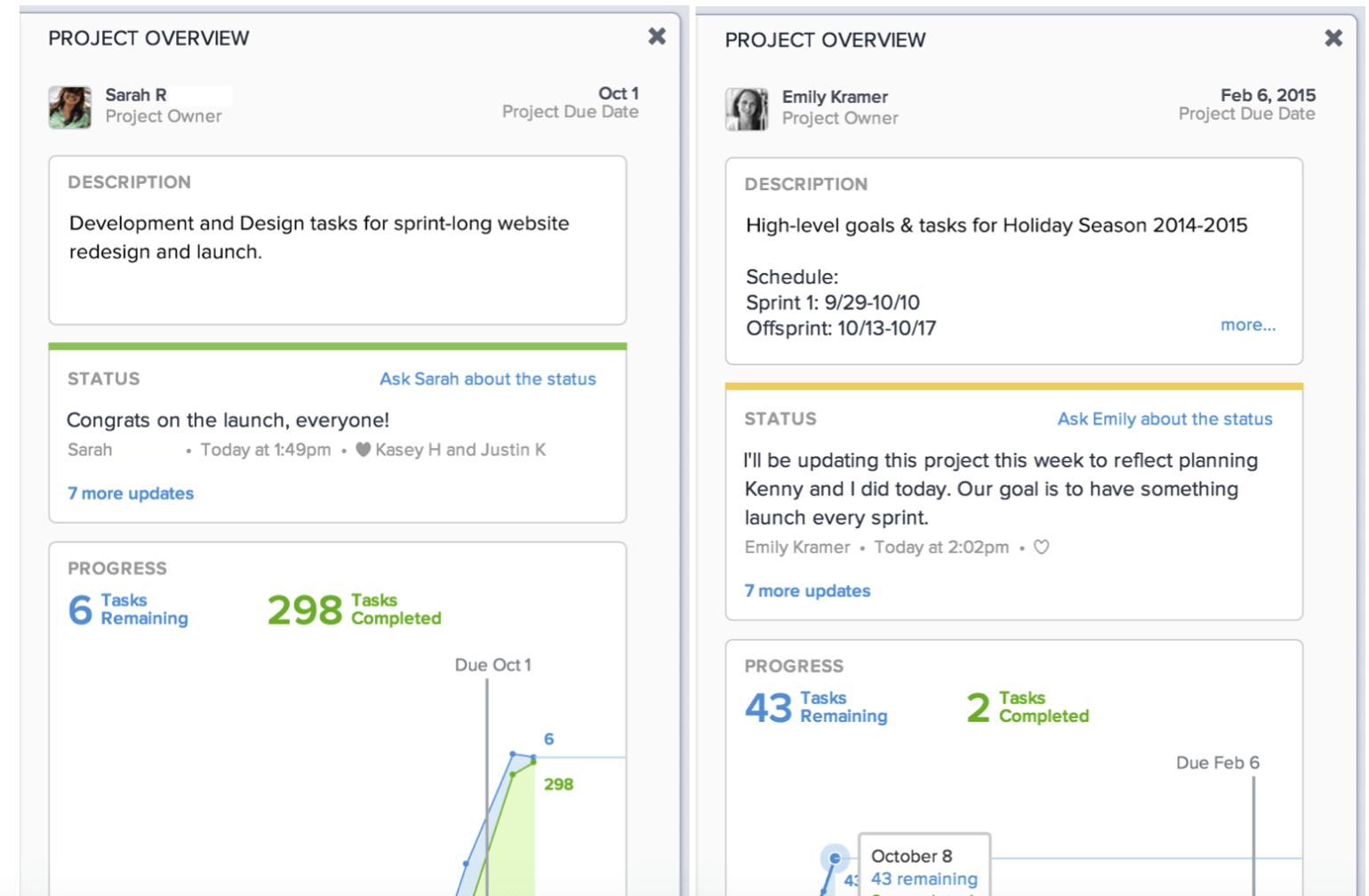

As Asana worked to help teams of all types and sizes, they realized users needed a way to track big picture progress. This was especially important to organizations with multiple teams that worked on several different projects and tasks. Asana’s answer to organizing this chaos was Dashboards. This had two parts: My Dashboard, which showed a user the qualitative and quantitative status of the projects that were most valuable to them, and Project Overviews, which allowed users to communicate progress and deadlines for a project with the rest of the team.

Dashboards further reinforced that every team in a company could use Asana—and that collaboration across teams would be easy and error-free.

In a few short years after their public release, Asana made a lot of product changes, added new features, and collected plenty of user feedback. They were iterating constantly and quickly. They weren’t afraid to toss things on the wall to see what stuck.

The end goal of all the testing was to grow usage and engagement within teams. Asana wanted to land and expand—first they wanted to get a foothold in as many teams as possible, and then they wanted to get more people within an organization using the Asana platform. Many of their new features, like Organizations and Dashboards, helped them achieve this goal by making cross-team collaboration more intuitive within the product.

But the one glaring issue that was still undermining engagement was the user interface and the user experience. To keep growing, Asana needed to figure out how to make their product more engaging.

2015-Present: Major app redesign and increased focus on the user experience

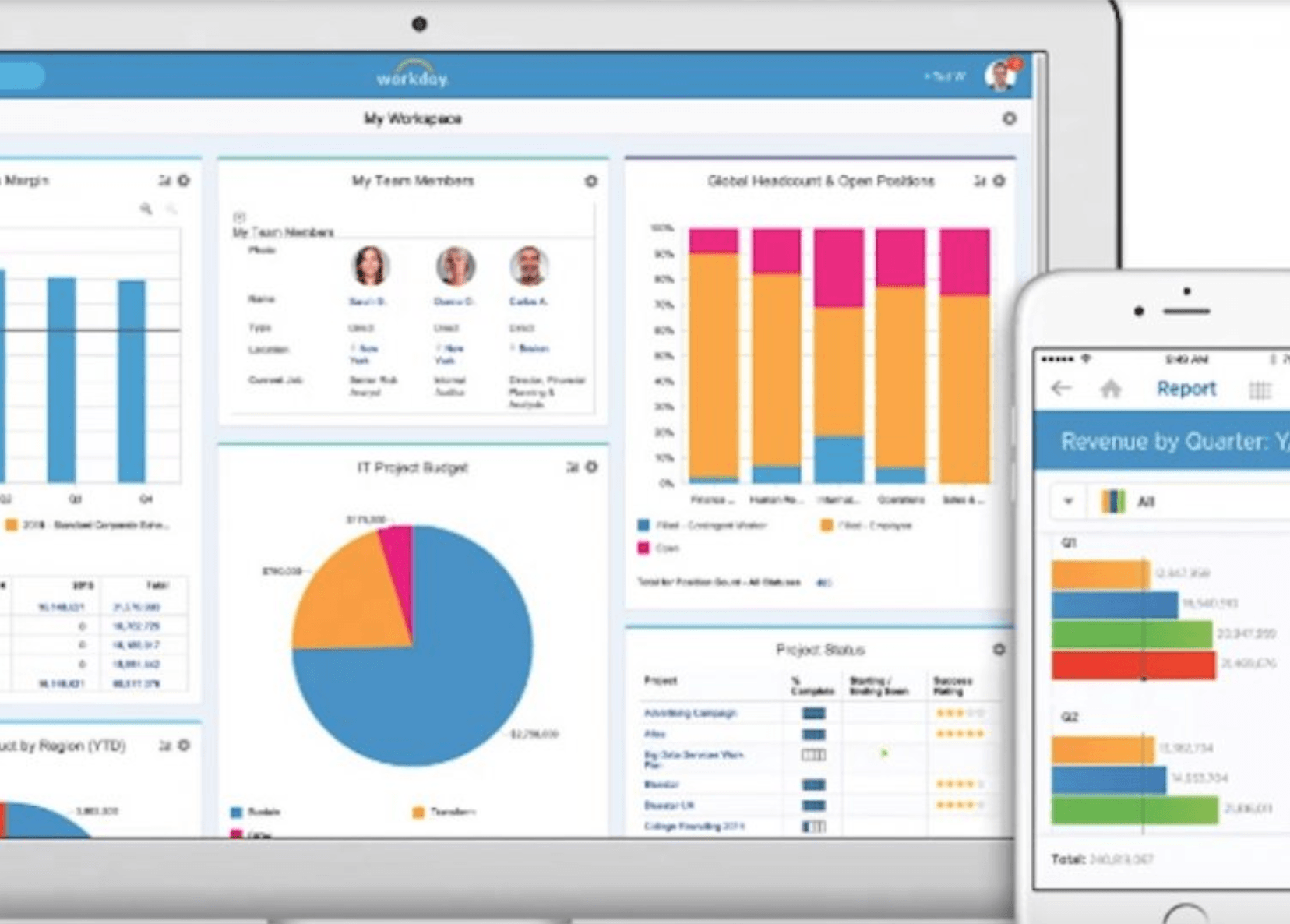

The beginning of 2015 marked a new era for workplace apps. One of the defining qualities? They all started to look fun:

This new landscape made it harder for Asana to meet its goal of creating a tool that all users could use and wanted to use. Asana’s UI was still clunky and corporate. To keep up with other workplace tools on the market, something had to change.

So Asana made a really smart move and overhauled their UI from the ground up. They rebuilt their interface—based entirely around user feedback—to improve engagement and growth.

Still, the Asana team knew they had to fix more than just the UI. They were playing in the crowded and competitive project management space with other beloved products like Jira and Basecamp. The bar was high and every detail of their user experience mattered, down to product speed and offline access. In the last few years, the team has worked to add and perfect details like these.

To gain more market share, Asana also set a forward-looking goal to widen the top of their funnel. In the most recent years, they’ve focused more on international markets and expanding enterprise offerings to really large organizations.

Let’s take a closer look at the smart moves they’ve made most recently to improve UI and UX and compete in a highly competitive space.

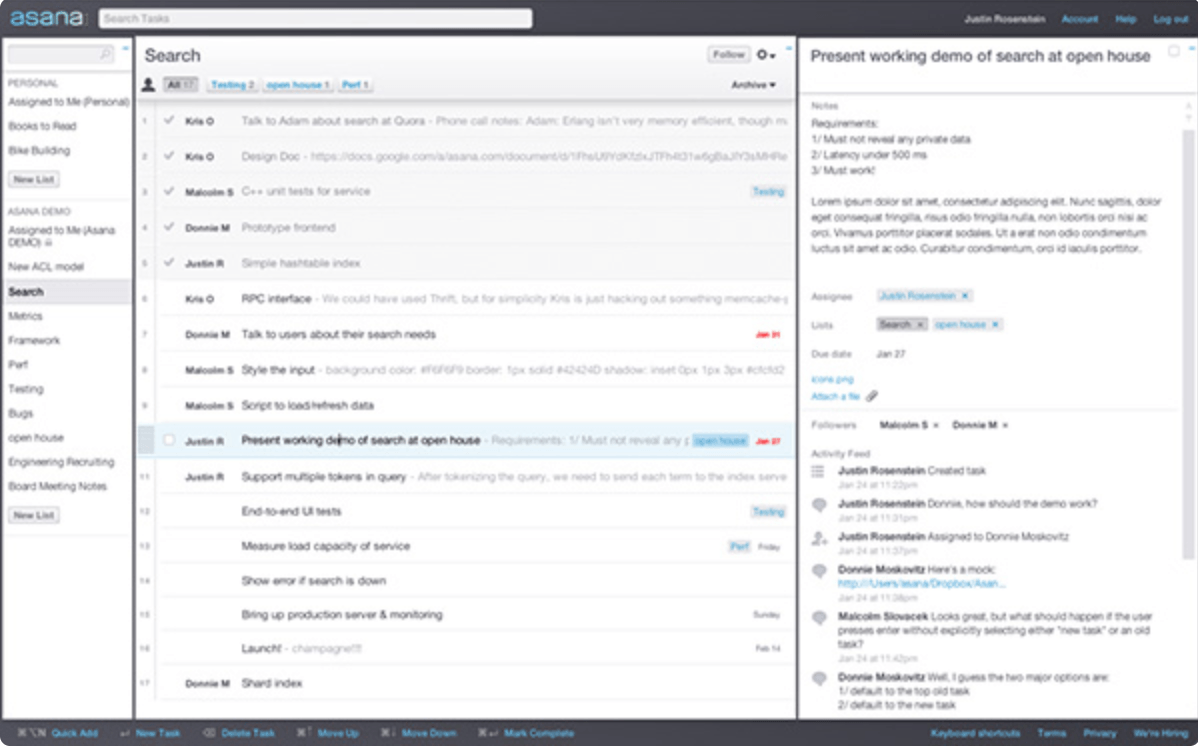

2015: In September, Asana launched a brand new redesign of their web app. They called it “New Asana.”

Previously, the team heard from users that their design was problematic. Users cited the design as the top reason why they wouldn’t recommend the product to a friend. NPS feedback revealed that a lot of users were simply confused by the UI. Recognizing these problems was an important first step for the company’s redesign. Product manager Sam Goertler said, “The key to the genesis of our redesign was that we first convened to solve a problem, not to implement a solution.”

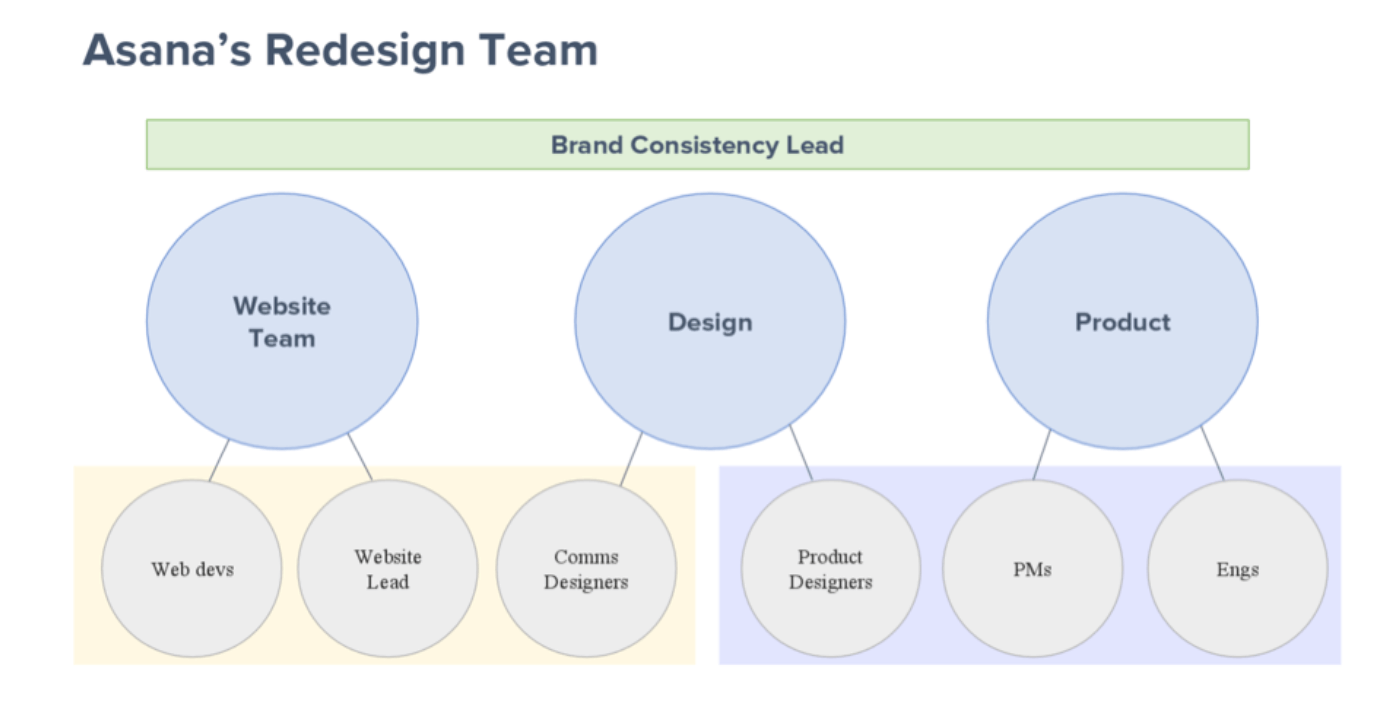

The next steps—redesigning from the ground up—were based entirely on understanding user workflows, looking at qualitative data, and collecting anecdotes. It was a multidisciplinary effort, with leads from development, design, and product all working together in a temporary cross-functional think tank.

On top of that, the team worked hard to think about how to roll out the redesign without interrupting the user experience.

“We realized that we could incrementally launch structural improvements in our old visual style without putting users through a Frankenstein UX. Once the structural changes were integrated, we could do a visual refresh in one fell swoop, having already mitigated the risk of user backlash because they wouldn’t have to change their workflows overnight. – Product Manager Sam Goertler

The effort paid off—users were thrilled with the new product. Reviews praised Asana for “making work fun again”—which had been their goal all along.

2016: A year after their redesign, Asana saw the effects of their improved UI. They now had 13,000 paying businesses as customers, up from 10,000 in September of the previous year. Additionally, the co-founders reported that ARR was “more than doubling” for the past 4 years.

In light of this success, Asana raised a $50 million Series C, led by Sam Altman and Y-Combinator. The round valued the company at $600 million—over double the valuation four years earlier at the time of their Series B. The team announced plans to use this capital to continue improving the product—including making it faster and more extensive. They also planned to continue hiring and growing the team.

Later in 2016, Asana opened up a new iOS private beta that included highly requested features like offline access. Features like these were not only essential for Asana to help people work wherever they were—they were also critical for meaningfully competing with other project management apps. If Asana didn’t keep up with the features users wanted, other apps would.

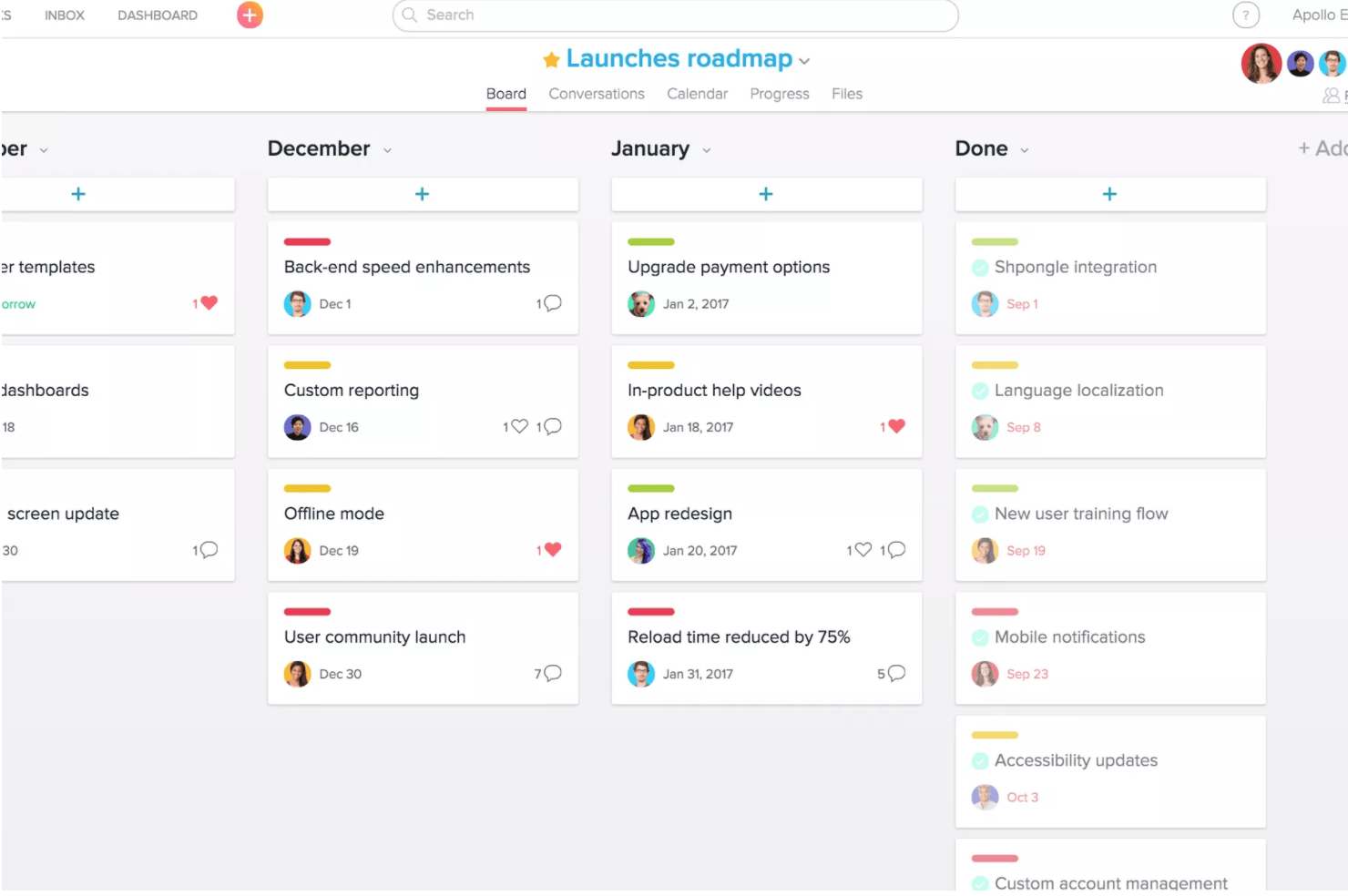

To keep expanding out their features around productivity, Asana released kanban boards similar to Trello’s boards.

Asana called their new boards “just one way to do work” within the larger landscape of all their product’s features. But the Asana team acknowledged their copy of Trello’s main functionality: “We want to give Trello full credit here,” Rosenstein said. “They’ve done a great job popularizing this easy visual view. But we see a much bigger opportunity here to enable more kinds of work.” Asana saw that the real power of these boards was in connecting them with everyone else you work with and all of the other data around your work. This gave them a competitive edge over apps like Trello that only provided one way to visualize work.

While some reviewers interpreted the move as a declaration of war, it’s more likely that Asana was just trying to keep up. Trello was blowing up in 2016 with over 1.1 million daily active users and it was becoming clear to everyone in the industry that this kanban-board style of organization was incredibly valuable to users. This bolstered Asana’s popularity even more because it gave users the option of simple visualizations within a more complex ecosystem of consolidated workplace data.

2017: In February 2017, Asana hired a new CFO Tim Wan and a new head of sales Oliver Jay. This was important to Asana’s growth because these new hires planned to focus specifically on international sales and enterprise expansion. Both hires had previous experience that prepared them well for these roles. Wan had helped take Apigee, an API management and analytics software company, public before it was acquired by Google Alphabet for $625 million. Jay built the U.S. sales team and global sales team at Dropbox. These two additions to the team were key players that knew how to scale.

For over a year, Asana worked on their biggest engineering undertaking ever: incrementally rewriting their entire infrastructure to make Asana run faster. Historically speed was a commonly-reported issue in the app. In August, Asana announced their most common actions, like loading Asana and switching tasks, were between 1.5x and 4x faster. The extent of this project in direct response to user feedback showed Asana’s serious commitment to continuously improving the user experience.

2018: Asana has not slowed down in product improvement or expansion. They’ve grown international sales, reporting now that 45 percent of their 30,000 paying customers are located outside of the U.S. In addition, both new and existing customers are still extremely happy with the product, reporting that they’re 45% faster and more efficient than they were before using Asana.

This all led to the company’s $75 million Series D earlier this year, which valued the company at $900 million. Asana says that they plan to use this new capital to focus on making Asana available in more languages, which has the potential to expand their user base exponentially.

Though Asana has gone through some big changes and improvements over the last several years, a lot has stayed the same.

The company still values company culture and employee happiness. They prioritize smart hiring and work to cultivate a diverse and open-minded workplace where employees can freely give feedback and can expect a high quality of life. They also still value user feedback and make iterations and improvements based on what their customers want.

Most importantly, even though they did a complete product redesign, the team and product stayed true to their mission to make a universally accessible tool that makes work easier for any user. A lot of newer workplace apps captured attractive markets, but the Asana co-founders didn’t use the redesign as an opportunity to create a Slack or messaging competitor. Moskovitz said their product was still “pretty different from a Slack channel” and maintains that “it’s really meant to be an email killer.”

Throughout their growth, Asana has made the effort to maintain a clear product vision and to create a repeatable process around user feedback. This makes me confident that no matter what’s next for Asana, they have a strong foundation for success.

Where Asana can go from here:

Though all of Asana’s iterations have been tightly related to product management, they’ve also done a good job of following market demand for certain key features. They’ve been willing to add kanban boards, calendars, dashboards, and more to make project management more fun and effective.

Going forward, there are endless project management features Asana could add to their product. Their smartest move would be to expand to other big markets with new products and features.

These are the three product categories around project management Asana could tackle next.

- Time tracking: Time tracking could be a natural fit within Asana’s project management landscape. The time tracking market currently has enterprise tools like Paycom and smaller, lightweight tools like Harvest. But there isn’t a tool that helps team integrate time tracking with project management and organization, which is where Asana could win the market. Time tracking is usually considered a function of HR and labor management, and it’s usually dreaded and underutilized by small teams. If Asana can make it as enjoyable and easy as they’ve made other project management activities, they could win over users in a new market and land and expand in more companies.

- Meetings: From the very beginning, Asana said they consider in-person meetings and whiteboards some of their biggest competition. If they build out meeting management software, they’d expand into another valuable market still tightly related to team organization and project management. Many companies see meetings as a necessary evil. Even though they take up a lot of time and create extra work for team members, they’re not going to completely disappear anytime soon. But Asana could build out a function in their tool that helps users create meeting agendas, record minutes, and share meeting insights with everyone on a team. Creating software that makes communication before, during, and after meetings easier would directly support Asana’s mission to reduce “work about work.”

- CRM: Down the road, Asana has potential to build a CRM extension of their project management tool. The size of the global CRM market has been steadily growing over the past several years—according to Gartner, it’s nearing $30 billion. While Salesforce dominates the enterprise CRM space and disruptors like ProsperWorks are provide more accessible solutions by integrating with G-suite, Asana can carve out a place for itself by tying customer relationship management to project management. An integrated CRM would make external communication around projects as easy as internal communication. It’s a natural extension, and as Asana grows, it will be interesting to see if they try to compete here.

3 Key Lessons to Learn from Asana

Asana is unique because they had a lot of early advantages that the average startup doesn’t have. Their founders were already well-connected in Silicon Valley, and Asana’s earliest users were personal friends and colleagues who ran their own multi-million dollar companies.

While these factors contributed to Asana’s success, they didn’t define it. Asana grew into the company it is today by building a strong product and a smart company around it. There are a lot of lessons that growing businesses can take away from Asana’s growth that are even more valuable than their auspicious beginnings. These are the three most important takeaways:

1. Clearly define what your company is and what it isn’t.

From the beginning, Asana made decisions that defined both their project management tool and company.

Asana was clear that they wanted to be a project management and collaboration tool that replaced email. They were also clear that they were not a chat tool or social network. If they wanted to be either of those things, they might have stayed under Facebook’s roof, or used their redesign in 2015 as an opportunity to build a better Slack.

The company also prioritized employee happiness and respect from the outset. Even though things like in-house yoga can seem trite, at that time it was a clear break from the other workplace cultures of Silicon Valley. By advertising these perks when scouting talent, they sent a message that their company was different and that they were building a team of people who appreciated healthy work-life balance.

Defining your company is easier than you think. I believe that asking two simple questions to everyone at your company can help you start to understand your product vision and company culture. These are the main points where you and your founding team need to agree.

- What are you working on?

- Why are you working on it?

Team members should be able to explain the product and its value to you like you’re five years old—it should be clear and succinct. It’s also incredibly important for team members to articulate why they’re working on something. The whole team needs to be on the same page about what’s important because these values drive all work and decisions at the company.

Simply asking people to think about these questions sparks important conversations and give everyone a better framework for making important decisions down the line.

2. Take the middle road between freemium and enterprise for widespread workplace adoption.

“There’s a rift in the enterprise world between the traditional top-down approach and the new bottom-up style. We’re taking a middle road that includes the best of both worlds.” – Justin Rosenstein

Asana’s freemium business model was essential to its growth. The free plan makes it really easy for a few team members at a company to try the product. Eventually, they start sharing projects and tasks with others and get their whole team in the product. Then, as the team collaborates cross-functionally with other teams in the organization, even more internal teams naturally adopt the product.

According to Rosenstein, in the early days, this gave Asana the advantage over other enterprise software solutions that were forced on employees by the company’s C-suite. Team members could try Asana themselves and encourage their teammates to use the product naturally.

On the other hand, Asana has been workplace software from the beginning, which meant it didn’t have to “pivot” to the enterprise like some consumer apps do when they want to grow. They were always in the enterprise space and thinking about this use-case.

For companies that want to find the best of both worlds like Asana, it’s important to:

- Clearly define the market you’re targeting and think ahead to where you want to be in 10 years.

- Consider how to reach that market in new, unsaturated channels.

Asana’s positioning was smart because they started out in the market they wanted to be in, but used a non-traditional business model to reach that market. As SaaS gets more competitive and channels get more saturated, this second point becomes increasingly important.

3. Be inspired by your competition.

Slack’s design and the rise of other next-generation workplace apps with fun, fresh UI showed Asana how outdated their design was.

Asana saw this challenge and responded with a completely redesigned product. Instead of trying to band-aid the issue, they went back to the drawing board and soliciting instruction directly from their users.

Product manager Sam Goertler recognizes that big overhauls such as the redesign come from a combination of internal and external factors, but places a lot of importance on pressure from competition. This kick in the pants from other companies was an important reminder for Asana that keeping up with the competitive landscape is exhausting but inevitable.

“There are more designers out there who are collectively advancing design languages and pushing visual styles forward. In turn that leads to a faster rotation of design trends. It’s a virtuous cycle… What it comes down to is that design trends are moving quicker than ever. As soon as a new style rolls out, the previous version seems incredibly outdated by comparison.” – Sam Goertler

It’s important for companies to be aware of this virtuous and unforgiving cycle of advancement. According to Goertler, these are the most important things for competitive companies to keep in mind when innovating in a competitive space:

- Reach out to your users to gain validation and confirmation. Your users are the thermometer you need when deciding to make a big change. Surveys and NPS feedback can be the concrete evidence you need to push you forward.

- Set a North Star to guide you through incremental work. You need one guiding metric—usually around customer engagement—to drive a big project forward through all of its small steps and iterations and to keep you on track.

- Solve a problem, don’t implement a solution. Your competition can highlight problems with your own product, but solve it in your own way. Don’t assume that your competition has the right answer for your product and don’t copy blindly.

- Expect a risk-averse stance from your team on making big chances. You’ll have to clearly explain the need and the benefit, and recognize that big chances are scary for stakeholders.

Your competition should serve as a source of inspiration, but not a blueprint. Look at everything in context—your competition, your industry, and especially your users—and then make decisions for your team and your product.

Onward and Upward to Universal Happiness

Asana started as a side project and spun off into a separate company with its own clearly defined goals and vision. Today, they’re still working to reach those same goals—but now, they’re doing it for hundreds of thousands of users as they grow their $900 million company.

They’ve had some struggles along the way to connect to such a large and varied market, but they’ve never strayed from their original mission or stopped iterating and researching. This is what has propelled them forward and allowed them to reach markets even beyond tech. Now, they’re truly an industry-agnostic product, serving teams in fields from healthcare to government to retail.

Maybe they really are on the way to growing universal happiness with enterprise software. I’m excited to see what’s next for Asana!