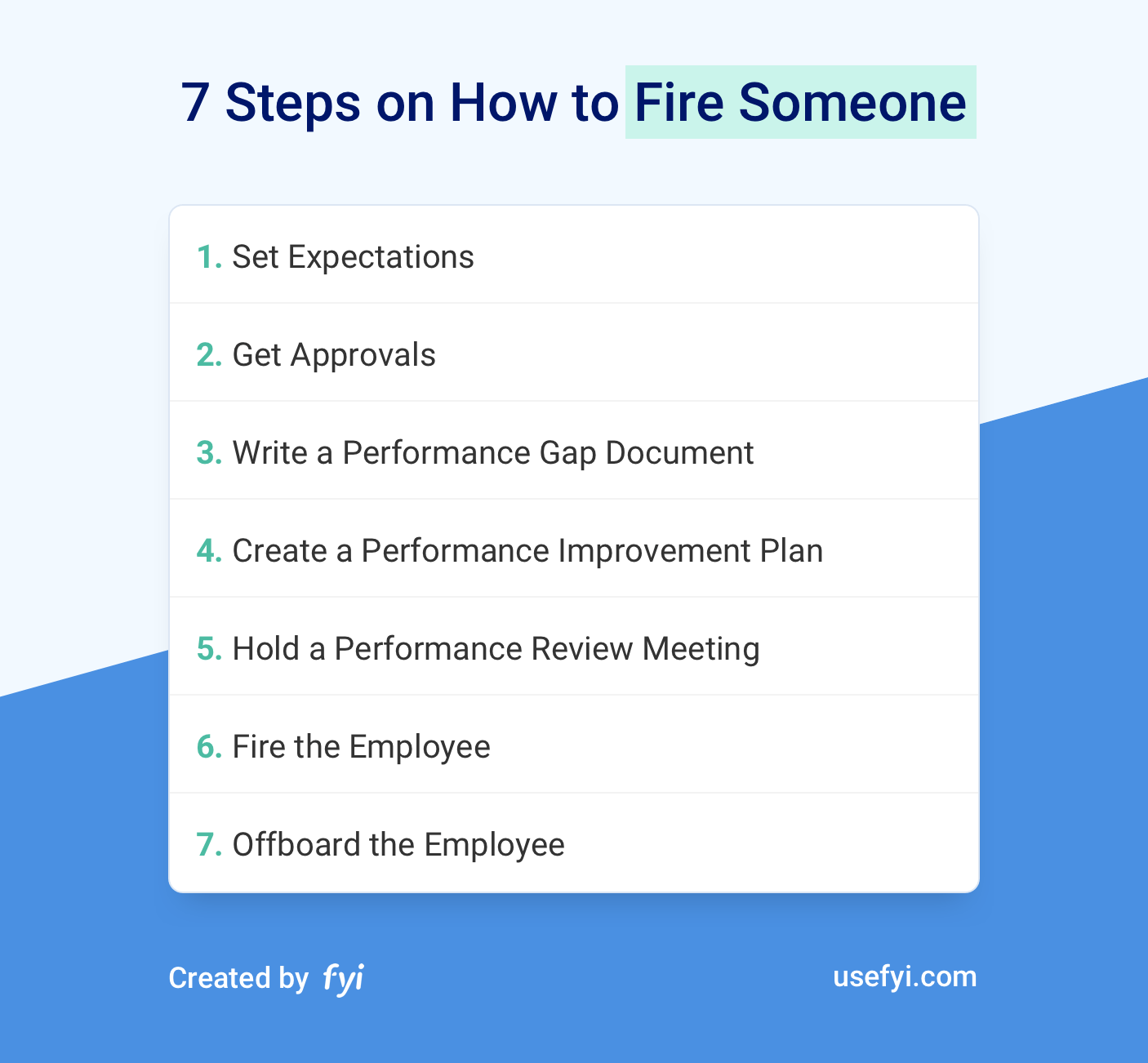

7 Steps on How to Fire Someone Without Getting Sued

By far, firing is the worst part of being a manager.

After years of managing teams and having to fire folks many times, I still get a pit in my stomach just thinking about it.

In my experience, that feeling of dread never goes away even after having a bunch of experience with this. It does get smoother though. After you’ve done it a few times, you’ll know each step. It’ll still feel awful, that never goes away, but you won’t be as nervous about the process itself.

So what’s the best way to go about firing someone?

Well, any firing process needs to find the balance between several goals:

- Keeping yourself and the company protected legally

- Doing things as gently as possible for the person being fired

- Giving the person plenty of chances to turn things around

- A smooth process that you can complete with the least number of problems

Depending on who you ask, some managers will overweight one of these elements more than the other. For example, some managers try to be as supportive as possible for the employee. And while that’s really admirable, it can create legal issues later or drag the process out way too long.

I’m going to outline the process that I’ve used in the past.

Whatever you do, be sure to run all this by your HR team and legal counsel. When it comes to firing, you always want to make sure you’re doing everything by the book.

When is it time to fire someone?

If I find myself asking this question, it’s almost always time to part ways.

For folks that are doing their jobs well enough, we never think about the possibility of firing them to begin with. If anything, we ask ourselves if we’re doing enough for those employees to keep them on the team.

But if things have deteriorated to the point where you legitimately ask yourself if someone should be fired due to their performance, it’s usually time.

The first few times that you have to fire someone, you’ll usually come up with any excuse to delay the decision. The thought seems so painful that you’ll readily look for reasons to give that person another shot. The first time I fired someone on my team, I delayed the decision at least 6 months longer than I needed to. This is really common.

We usually have a habit of delaying the decision too long. And I have never met a manager that wished they waited longer.

So if you’re asking the question if someone should be fired, they probably should.

Here’s a good way that I’ve used to clarify the decision. Ask yourself: “If you had a chance to hire that person today to fill the same role, would you do it?” If the answer is no, it’s time for a change.

Let’s say that you’ve determined something needs to change. There’s an entire process we need to run through first for a few reasons:

- We need to make sure we’ve set expectations on exactly what’s required for the role

- We need to give this person a genuine chance to turn things around

- We have to make sure there’s no bias in the decision and that firing is purely for performance reasons

Step 1: Set Expectations Clearly With the Employee

Before you begin the firing process, you’ll want to do a round of expectation setting and coaching. Start this whenever you see any gaps with the employee’s performance and the responsibilities of the role.

Assume the employee is acting in good faith, is genuinely trying their hardest to accomplish their goals, and give them as much support as possible.

The tool that I’ve found most helpful during this step is to have an internal job description.

It’s pretty similar to the normal job descriptions that we’re all familiar with during recruiting. The main difference is that the internal version goes into more detail. If anything, it should go into too much detail. The goal is to cover every responsibility of the role as clearly as possible. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity at all.

Here are a few tips that I’ve learned for these internal job descriptions:

- Every item should be clear enough that it’s easy to determine what “done” looks like. For example, if you ask a marketer to “improve the brand of the company,” how do you determine that it’s been improved? When there’s ambiguity, there’s room for disagreements for what good performance looks like. This level of clarity is difficult to achieve for many roles but it’s a critical part of great management.

- List every last expectation that you have. If the requirement isn’t written in the internal job description, assume the employee won’t do it. This will make sure you’ve set every expectation that you care about for the role.

- Get a few rounds of feedback from folks in that role. This will flag any areas that are unclear or confusing. In every job description that I’ve ever done, there were always a few items that didn’t make sense to my employees. One or two rounds of feedback will improve the internal job description immensely.

Once you have an internal job description that’s solid, use it when reviewing performance gaps with any employee as they come up. By writing down the expectations, they carry a lot more weight. You’ll get fewer debates from employees and everyone will focus on solutions instead of excuses.

Show the employee the internal job description, highlight the part that’s relevant, then give specific examples of where performance isn’t meeting those expectations. I then like to ask the employee what specific actions they’re going to take in order to close the gaps. If their ideas aren’t likely to solve the problem, I’ll coach them to a few better ideas.

In the vast majority of cases, performance gaps will go away after you have these discussions.

For employees that are struggling, I’ll do 2-3 rounds of this informal coaching and expectations setting.

Once you start noticing that you’ve had to address the same problem with the employee multiple times, start documenting everything. Keep screenshots, make notes of all your meetings, document anything relevant. That’ll make a lot of the following steps a lot easier and help protect you legally.

But what happens if performance doesn’t improve?

Then it’s time to begin the formal process.

Step 2: Get Approvals from Your Manager and HR

At this point, you’ve already coached the employee and clearly communicated what’s expected of them.

And they’re still not meeting those expectations.

It’s now time to start the formal process of a performance improvement plan.

First, go to your manager and outline the problems that the employee has been facing. You should have some documentation on hand for the issues so you’ll have everything you need to make your case.

Second, go to HR and get their approval as well. They’ll usually ask for any documentation that you have and to confirm that expectations were set correctly with the employee. This is where the internal job description comes in handy.

Of course, if your HR team has a process for termination already, follow that process perfectly.

Assuming everything has been documented appropriately, the approvals should be easy to get. Then you can move forward.

Step 3: Write a Performance Gap Document

While you should have plenty of notes at this point, they’re probably a bit disorganized.

It’s time to clean them up and put them together in a polished document that you can share directly with the employee later. This document will outline in exact detail which gaps continue to persist for the employee. Make it as clear as possible and include specific examples.

Have your manager and HR approve this document.

Step 4: Create a Performance Improvement Plan

After you’ve documented all the gaps, write out a performance plan for the employee.

I know performance improvement plans can get a bad rap. They accomplish two major tasks for you:

- They add more documentation and formality to the firing process which adds more protection during any legal actions later

- They do give the employee one more genuine chance to turn things around

This performance improvement plan should outline in exact detail what needs to change for the employee in order to keep their position. You’ll want to include multiple objectives on what needs to change during this period. Don’t let any ambiguity sneak into these goals. If you do have to fire the employee later, it should be blatantly obvious that these expectations were not met.

Usually, the plan should last about 30 days.

Also get your performance improvement plan reviewed by your manager and HR.

Step 5: Hold a Performance Review Meeting

Now that you have all your documentation, your performance improvement plan, and your approvals, it’s time to notify the employee.

These meetings are always stressful. Here’s an agenda to walk you through it:

- Tell them their performance so far hasn’t met the expectations of the role

- Outline the exact expectations they need to meet

- Go over the examples of them not meeting expectations that you’ve documented

- Tell them they’ll be on a performance plan going forward

- Describe the exact expectations of the performance plan and when they need to meet them

- Tell them that failure to meet the expectations of the performance improvement plan can lead to termination

During these meetings, I’ve tried to avoid telling the employee what’s at stake. No one likes to tell a teammate that they might be fired. Don’t give in to that temptation, the employee must know that they could be fired. If the process has gotten this far, there’s a good chance that the employee isn’t accurately evaluating their own performance. That’s why it got this far to begin with. So unless you tell them they could get fired, they’ll believe they still have more chances to turn things around.

Follow up after the meeting and include a summary by email that you reviewed during the call. Put everything in writing so you have more documentation on your end. Also include a copy of the performance gap document so they can review it on their own time. Be sure to include in your email that failure to meet the expectations of the performance improvement plan can lead to termination.

Hopefully, the employee absorbs this information and turns things around.

Step 6: Fire the Employee

If you get to the end of the performance improvement period and performance still isn’t meeting expectations, it’s time to fire the employee.

Again, get approval from your manager and HR before proceeding.

Once you’re ready, schedule the meeting for termination.

Follow these tactical steps for scheduling:

- Set the last day with HR. Block off time on your calendar for yourself and someone from the HR team to assist you that morning.

- I’ll typically send out a generic meeting invite to the employee the night before their last day. This ensures they’ll be available.

- Schedule the meeting for first thing during the day.

- Have someone from HR attend the meeting. If you don’t have an HR team, ask another senior manager to join you as a third-party observer.

For the meeting itself, you’ll hear different opinions on how to hold the meeting. Some folks recommend being very emphatic, telling the employee why they’re being let go, and offering to help find new roles.

In my experience, that opens the door for a host of problems. While some folks are grateful and leave gracefully, quite a few use the opportunity to debate the decision or respond in anger. That causes a lot of unnecessary frustration on both sides.

I prefer to keep the meeting script pretty tight. I tell the employee that today is their last day, the decision has already been made, I don’t go into the reasons at all, I explain there’s nothing else the employee needs to do in order to hand off projects, and that I’m happy to answer questions about the logistics of next steps but won’t be reviewing the decision. If they try to debate, I repeat that the decision has already been made.

Essentially, this is the “rip the band-aid” approach. It’s not fun but it gets it over with as cleanly as possible so everyone can move on.

Step 7: Offboard the Employee

HR should have everything in place to shut down the employee’s access as soon as they’ve been told that they’re being fired.

You want to make sure this happens immediately. When firing employees, some of them can lash out. So any lingering access can be a security risk. Get all critical logins and access shut down immediately.

While employee resignations can have an offboarding process that lasts several weeks, offboarding during a termination should get completed in a single day.

What about severance?

When terminating an employee, it’s usually a good idea to offer severance. Not only is it the right thing to do in order to help people through the transition, but you can also make the severance contingent on getting whatever documents signed that your legal counsel requires. This helps protect you from any wrongful termination suits.

A lot of companies will offer variable severance based on how long the person has worked for the company. One month of pay per year works as a standard rule. If you’re not sure, offer two months of pay. Whatever you decide to do, keep it consistent across the company.

How should you announce the termination to the team?

First, don’t call it a termination. Tell the team that today is the employee’s last day and that you wish them the best of luck with their future endeavors. If anyone asks why, tell them you’re not able to go into the details.

There’s simply too much risk for the employer from giving any details. If word gets around and impacts the former employee’s ability to get a job elsewhere, there could be a liability for the company. Even if it’s confusing for the team, don’t give any details about why the person left the company.