How Airtable Became a Unicorn by Reinventing the Spreadsheet

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the most exciting software products aim to solve the most mundane problems—problems that millions of people wrestle with every single day. These products might not be as interesting as the latest machine-learning startup, but they’re the products that solve difficult problems and make people’s lives better.

Airtable is a case in point.

Founded in 2012, Airtable is an alternative to one of the most critical, yet often overlooked, software tools upon which much of society relies—the humble spreadsheet.

Airtable’s founder, Howie Liu, didn’t want to make a better spreadsheet. He wanted to reinvent the spreadsheet entirely. Liu’s vision was to empower people to create what are essentially applications without writing a single line of code. Despite the countless applications of spreadsheets in almost every aspect of everyday life, Liu felt that most people were using them in ways spreadsheets were never meant to be used. According to Liu, spreadsheets are powerful tools, but they simply weren’t designed for the kinds of things most people use them for.

Here are a few things I’ll be taking a look at in this article:

- How Airtable empowers non-technical users to create engaging applications without writing code

- How Airtable quickly found its place in a competitive market dominated by large, legacy players

- Why the diversity and flexibility of Airtable is as much a liability as an asset

To understand Airtable, we need to understand the landscape of productivity software in 2012––and why such a gaping hole in that market created a unique opportunity for Liu and his team.

2012 – 2014: Welcome to the Grid

Years before his second company (Airtable) reinvented the database, Howie Liu wanted to make email a more useful tool for salespeople.

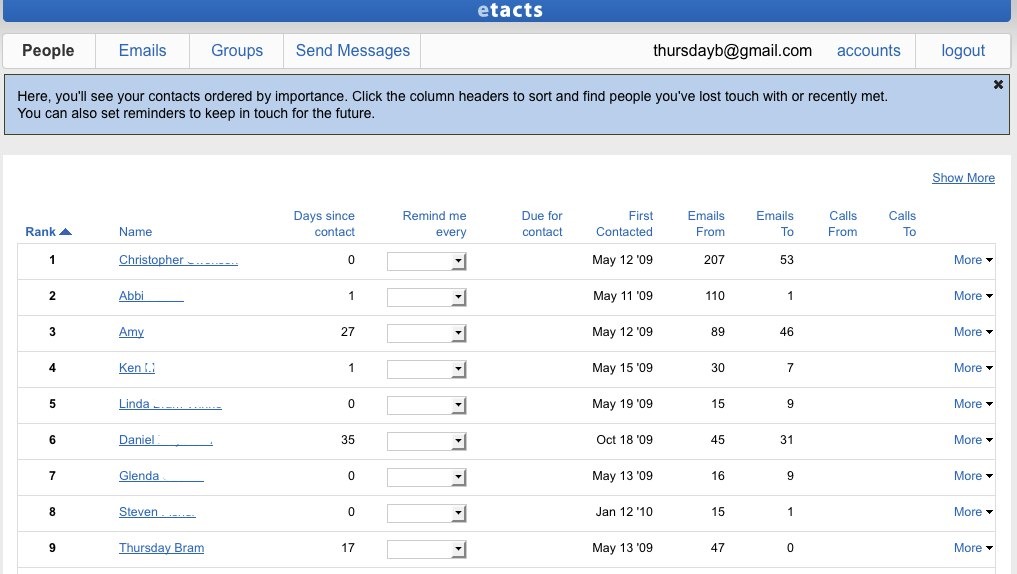

Liu’s first startup was Etacts, which he founded in 2010. The idea was simple. Etacts was a CRM for email contact management. Liu’s nascent company raised $700,000 from a range of angel investors, one of whom was the actor and tech investor Ashton Kutcher, who approached Liu after seeing a demo of the product at Y Combinator’s Demo Day in 2010.

Etacts didn’t last. The product showed promise but was shut down after less than one year in operation when Marc Benioff’s Salesforce acquired the fledgling startup for an undisclosed sum. Salesforce wasn’t alone in its interest in Liu’s contact manager product. Several other companies were courting Etacts with offers. Although Etacts was short-lived, Liu was already trying to solve the problem of how people could derive more value from their data––a problem he would tackle even more aggressively with Airtable.

Although Liu later told Business Insider that he had personally made “in the low seven figures on day one at Salesforce,” Liu also said that one of the main reasons he sold his company to Salesforce was the CRM giant’s primary focus on the enterprise. Liu admired Benioff and the way he had worked his way through the ranks at Oracle and wanted to learn more from him.

Liu spent a year as a Product Manager at Salesforce. However, Liu’s time at Benioff’s company was short-lived. He left Salesforce after just one year––this time, to pursue an idea for another product.

That product was Airtable.

Liu’s time at Salesforce taught him many things, but arguably the most valuable insight Liu gained from his tenure at Salesforce was how many people were using spreadsheets as purely organizational tools. Despite spreadsheets’ natural applications in bookkeeping and other primarily numerical tasks, Liu discovered that most spreadsheets were cluttered, haphazard containers for various data.

“Spreadsheets are really optimized for numerical analysis and financial calculations. But almost 90% of spreadsheets don’t have formulas. Most are used for organizing purposes.” — Howie Liu, founder, Airtable

While Liu saw a clear opportunity to redefine what spreadsheets could be, he didn’t want to just make a better spreadsheet. Liu realized that he could create an entirely new type of product that empowered users to create what were essentially simple applications and in a way that many users would find familiar and intuitive.

Liu and his co-founder Andrew Ofstad, a former Googler who had spearheaded the redesign of Google Maps, set about creating their first prototype. Once they had an MVP, they needed funding––so they visited Ashton Kutcher on the Warner Bros. lot in Los Angeles while Kutcher was filming episodes of his sitcom, Two and a Half Men. Kutcher was immediately impressed with Liu and Ofstad’s prototype, which Liu and Ofstad demonstrated in Kutcher’s trailer, telling the two founders that “I can really see this taking off, beyond Hollywood.”

Kutcher decided to invest in Airtable on the spot. Liu and Ofstad’s prototype also garnered interest––and funding––from several other investors, including Bebo founder Michael Birch and ZenPayroll CEO Josh Reeves.

“Even in my own world, I could see hundreds of different use-cases. They have spreadsheets tracking all these different stuff, it’s one giant organizational problem.” — Ashton Kutcher, investor, Airtable

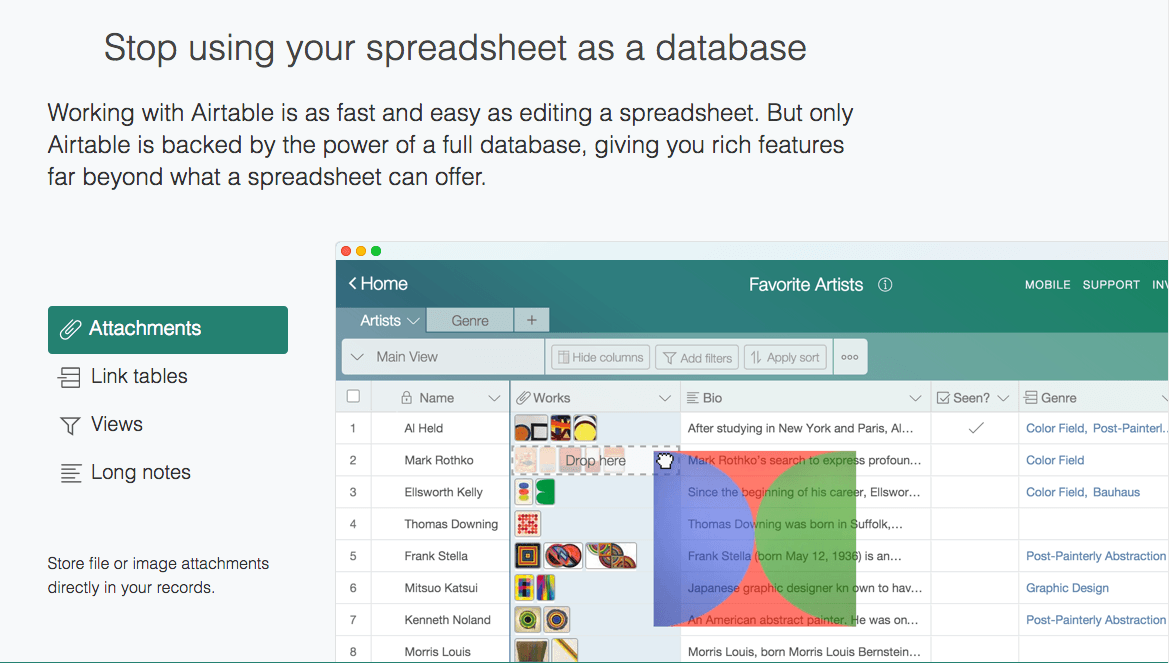

Airtable was officially founded in 2012, but development took place behind closed doors for two years. The earliest versions of Airtable focused primarily on the concept of a grid. Many people have described Airtable as “a spreadsheet on steroids” due to the similarities between Airtable’s grid-based UI and the typical spreadsheet. However, it’s important to understand that even the earliest versions of Airtable were far more than powerful spreadsheets. In actual fact, the product was (and is) much closer in form and function to a database––it just looks a lot like a spreadsheet.

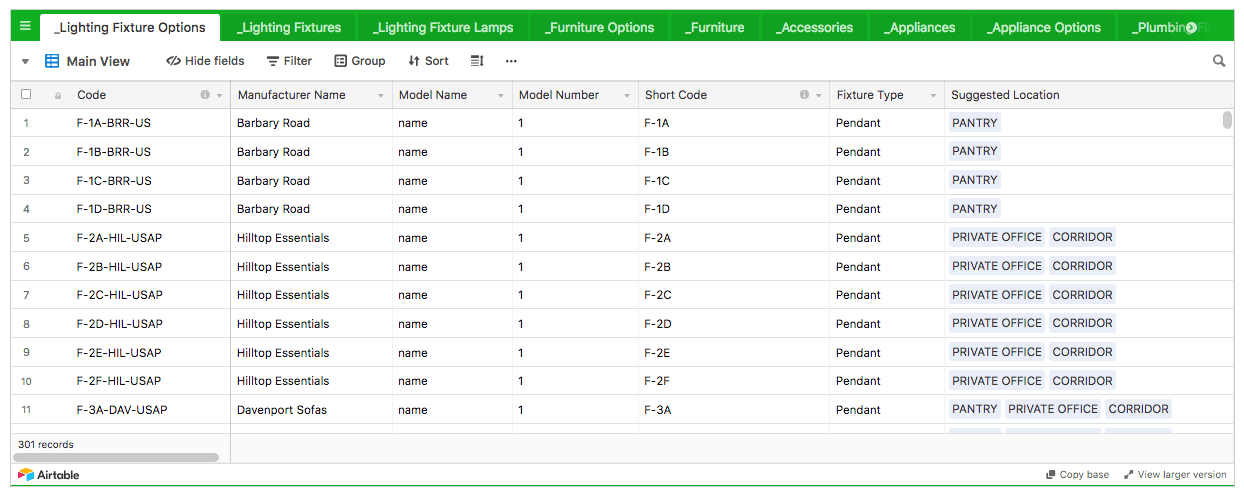

This subtle yet important distinction is what made Airtable so powerful. Unlike the cells of a spreadsheet, which are typically restricted to alphabetical or numerical data types, Airtable’s grid is a representation of many different data types––including files, contacts, and events, to name a few. Users could view and manipulate many different kinds of data because those data types were true records. By allowing users to work with several different data types within a single grid-based layout, Airtable gave users the power to connect and work with all their data in one place and create simple applications.

The real brilliance of the product was the ability to do all this without writing a single line of code. There was no need for server-side scripting or knowledge of SQL, which made the product very consumer-friendly. The product’s accessibility also made it potentially attractive to a much wider target market.

Liu’s instincts about the potential for an innovative spreadsheet/database hybrid were right on the money. Another factor that allowed Airtable to gain vital ground early on, however, was the commercial spreadsheet and database software landscape at that time.

Microsoft had been the undisputed king of productivity software for 20 years by the time Airtable went into development in 2012. What Microsoft––and virtually every other software company in the world––had failed to do was create a new spreadsheet product that people wanted to use. The ubiquity of Microsoft Office guaranteed Excel’s “success,” but it was stagnating as a product. Aside from some relatively minor performance updates and a handful of newer features, Excel looked and felt much the same as it did when it launched in the early ’90s. Microsoft’s Access had fared a little better (for a 26-year-old product) but was still aimed squarely at database administrators who possessed the programming and scripting skills necessary to work with SQL databases.

After two years in development, Airtable was officially launched as part of an invite-only open beta in 2014. Word began to spread about the product, and early adopters were very enthusiastic about Airtable’s potential. In a smart move to quickly convey the value of Airtable to prospective users, Liu’s observations about the common use of spreadsheets as organizational tools featured prominently in Airtable’s messaging:

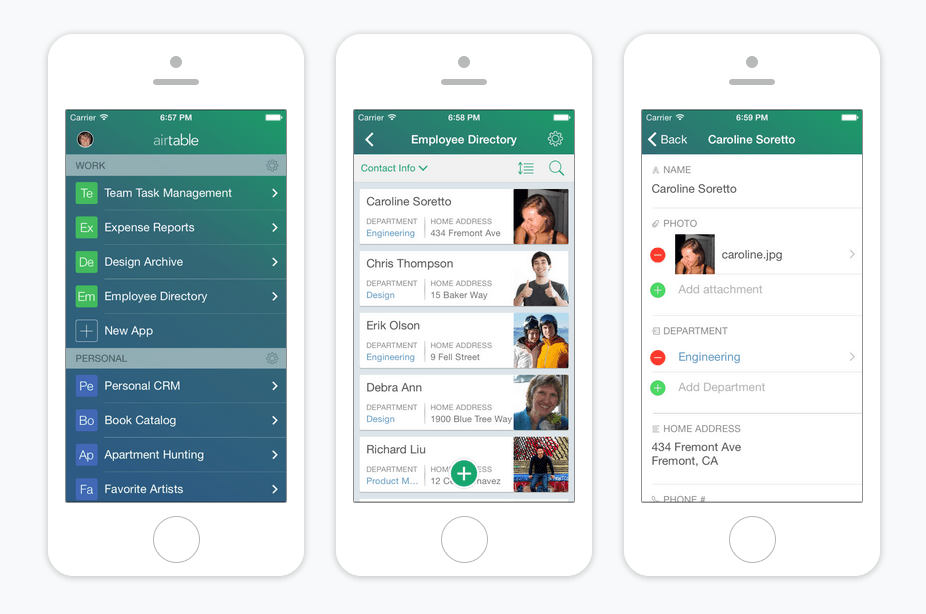

Another smart move on Airtable’s part was making its iOS app available at launch. This helped Liu and Ofstad get their product in front of more people. More importantly, it allowed users to access a remarkably powerful yet lightweight database on the go, wherever they were.

Even the very first iteration of Airtable’s iOS app was beautiful. Its minimal interface was effortless to navigate, its drag-and-drop functionality was immediately intuitive, and Airtable’s preset templates helped users get to the epiphany moment much faster.

Airtable was a great idea with real potential. However, for the company to even come close to achieving its considerable ambitions, it had to raise a lot of money––fast.

2015 – 2016: Democratizing the Database

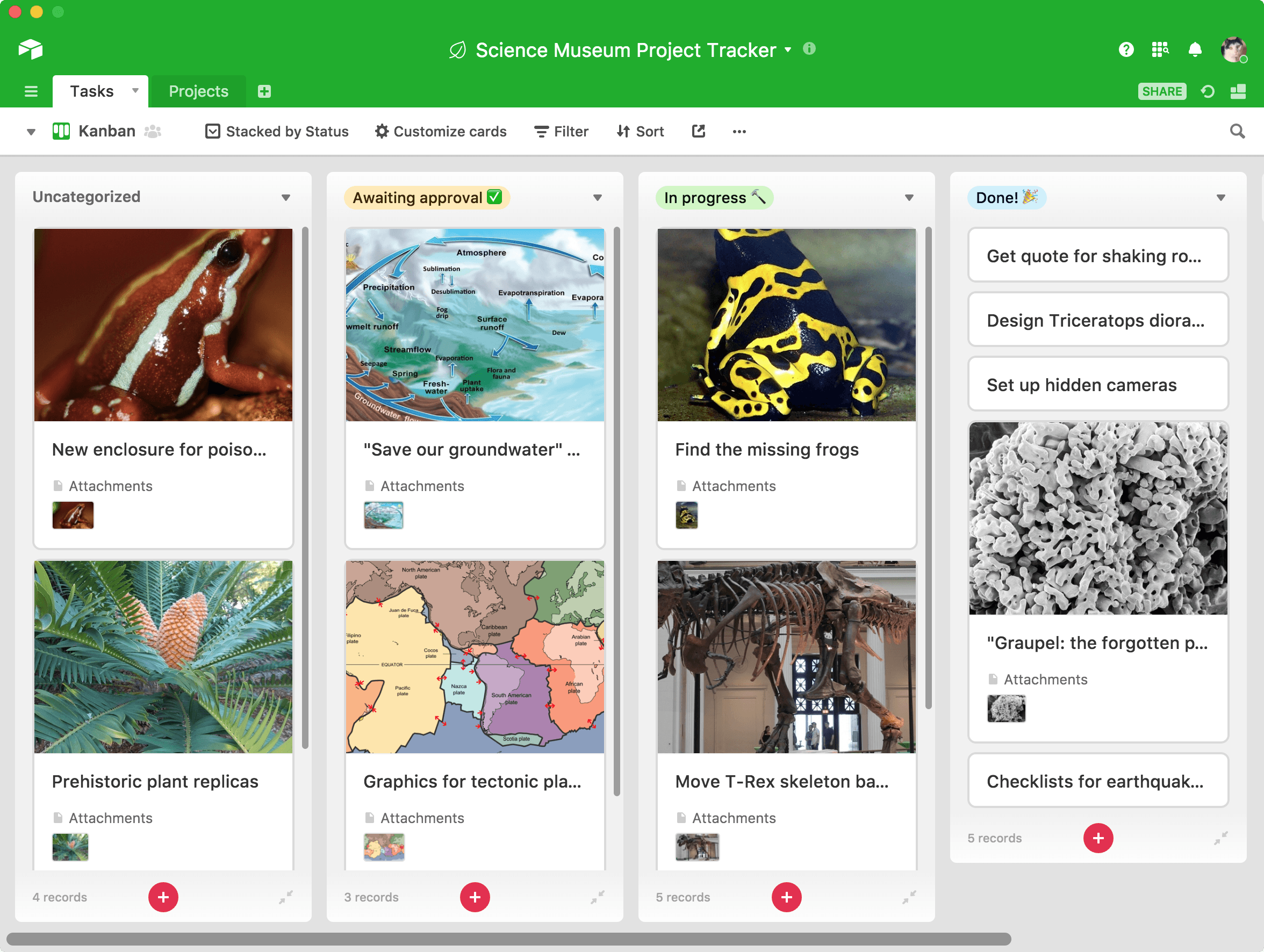

Airtable began 2015 with a strong product that had acres of potential. However, for Airtable to expand and implement more features, the company needed funding. The period from 2015 to 2016 was pivotal to the company’s growth and the development of Airtable as a product. Airtable’s initial product allowed users to flexibly organize their information in an easy-to-use grid. The next step was building out more “views” to help users organize that information in more useful and intuitive ways with its calendar and kanban views.

Liu’s company kicked off 2015 by raising $3M as part of its seed round in February, led by Caffeinated Capital. Shortly after this infusion of cash, Airtable was finally released to the public in March. The product’s preset templates had proven popular with new users, but even the company was surprised by the creative ways people were using the product.

“We’re seeing people using our tools in ways we never could have imagined—preserving ancient languages, tracking scientific equipment, managing construction projects, and even planning a U.S. presidential campaign.” — The Airtable blog, June 2015

Airtable kept up this momentum. In April 2015, the company unveiled its API Builder and its embedded database features. The API Builder was especially significant as it allowed users to pull records from their underlying databases and integrate that data into external apps and websites seamlessly. This was a great example of Airtable delivering on Liu’s original vision. Liu had long sought to give users the ability to create essentially standalone applications using Airtable, and its API Builder was a logical and welcome extension of that mission. The ability to embed data was ideal for less tech-savvy users who lacked the technical chops to work with Airtable’s API, which was a smart way to expand the functionality of Airtable for these users.

A month after Airtable launched its API, the company raised $7.6M as part of its Series A round led by CRV. In addition to the windfall of cash, Airtable also managed to tempt Francis Larkin, former Director of Product Marketing at Facebook, to join the company as its VP of Growth. A seasoned veteran of scaling products to new heights of growth, Larkin was a well-timed strategic hire that signaled the company’s intentions to grow rapidly.

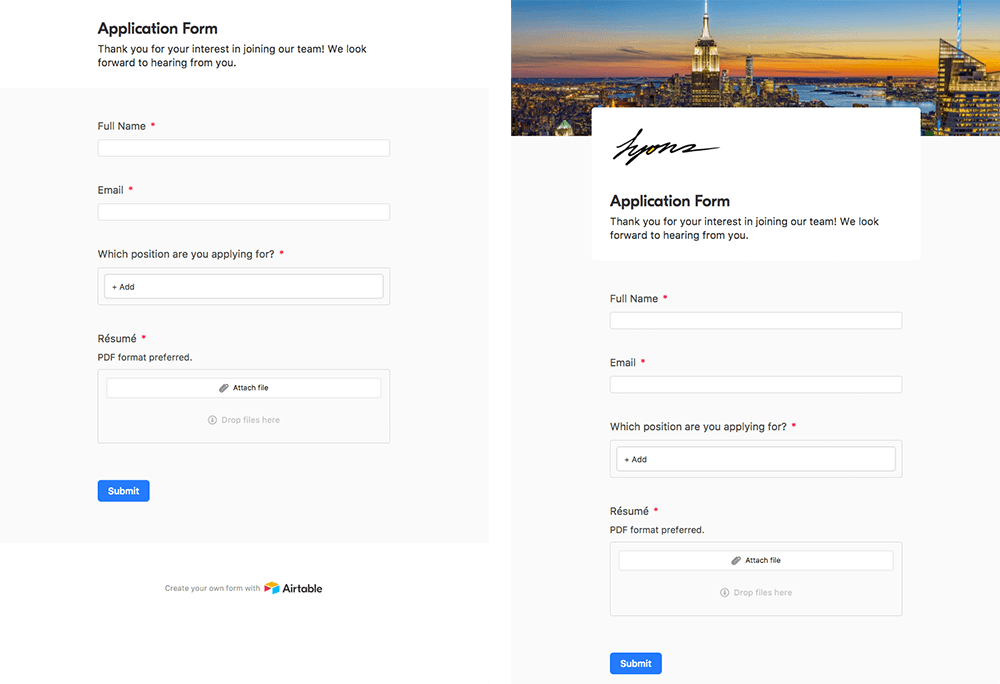

Hot on the heels of its latest round of funding, Airtable continued to develop and improve the product. In July 2015, Airtable unveiled Forms. Although the concept of form fields in simple database applications was nothing new, Airtable’s forms were as robust and flexible as its other features. Teams could create simple forms that connected directly to the relational databases that made Airtable so powerful. This functionality expanded Airtable’s potential uses considerably, and teams soon began using forms to build apps to support everything from simple contact forms to bespoke CRMs.

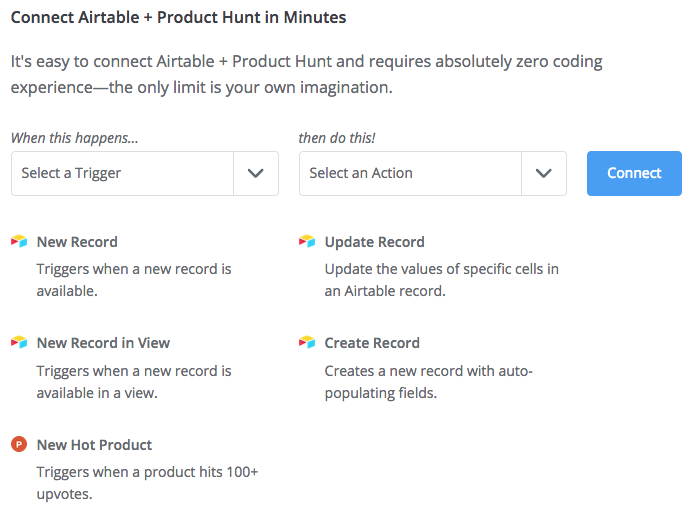

Airtable continued to roll out new features that summer. In August 2015, the company announced one of its biggest improvements to date––Airtable Integrations. Built using automation tool Zapier’s API, Integrations allowed users to connect their Airtable databases to more than 450 apps and products, from Google apps and GitHub to Slack and Twitter.

From Airtable’s perspective, this was both incredibly smart and a little risky. By building its integrations on top of Zapier, Airtable had far less technical overhead to worry about. This also allowed Airtable to offer an incredible range of integrations practically overnight rather integrate with one product at a time. However, it also meant that Airtable was entirely dependent on Zapier as a technical partner. As unlikely as it seemed, if Zapier went under, Airtable would have to find another way to maintain the integrations with external apps that many users would come to rely upon.

Later that month, Airtable introduced a new form field type: barcodes. Airtable supported 16 different barcode formats (including QR codes), meaning that Airtable users could now track physical assets using barcodes in their Airtable bases. Airtable had made it easy to keep track of digital assets from Day 1, but now, Airtable could be used to manage inventory in a wide range of environments, from warehouses to libraries.

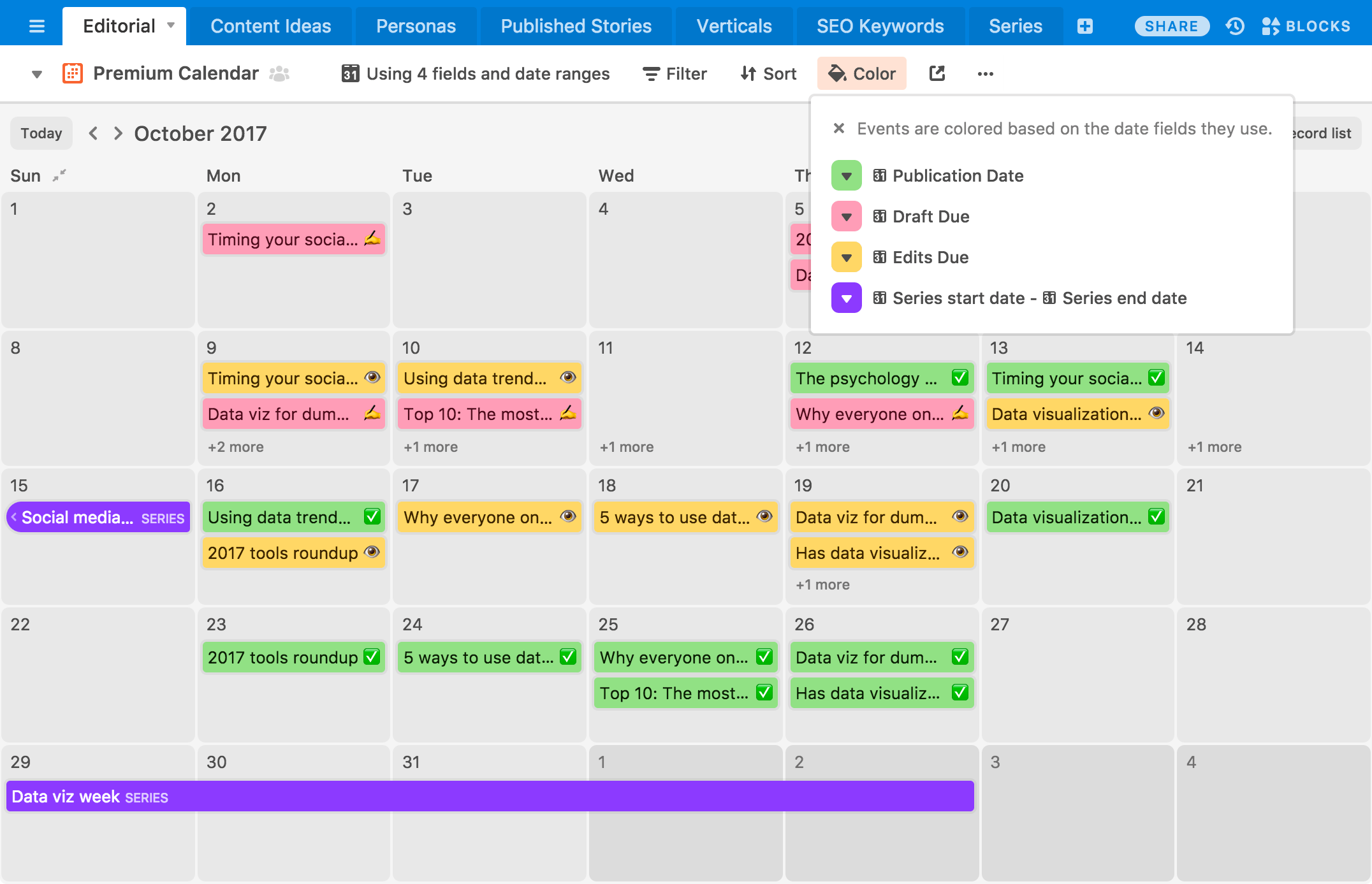

The next major product update came four months later in April 2016 with the introduction of Airtable’s calendar view. This was arguably one of the most important updates to the product during this period. Now, Airtable users could create databases that allowed team members to organize their data by date––a feature that was incredibly useful to teams that relied upon timely information. Editorial publication schedules, appointment management, competition deadlines, and a wealth of other event-based databases could now be created with ease. Even more useful was the fact that users could create custom views based on the data that mattered to them by applying various filters to those views. And, most importantly, Airtable’s intuitive UI made it effortless to switch between grid and calendar views, and users could easily drag and drop calendar events to arrange their schedules.

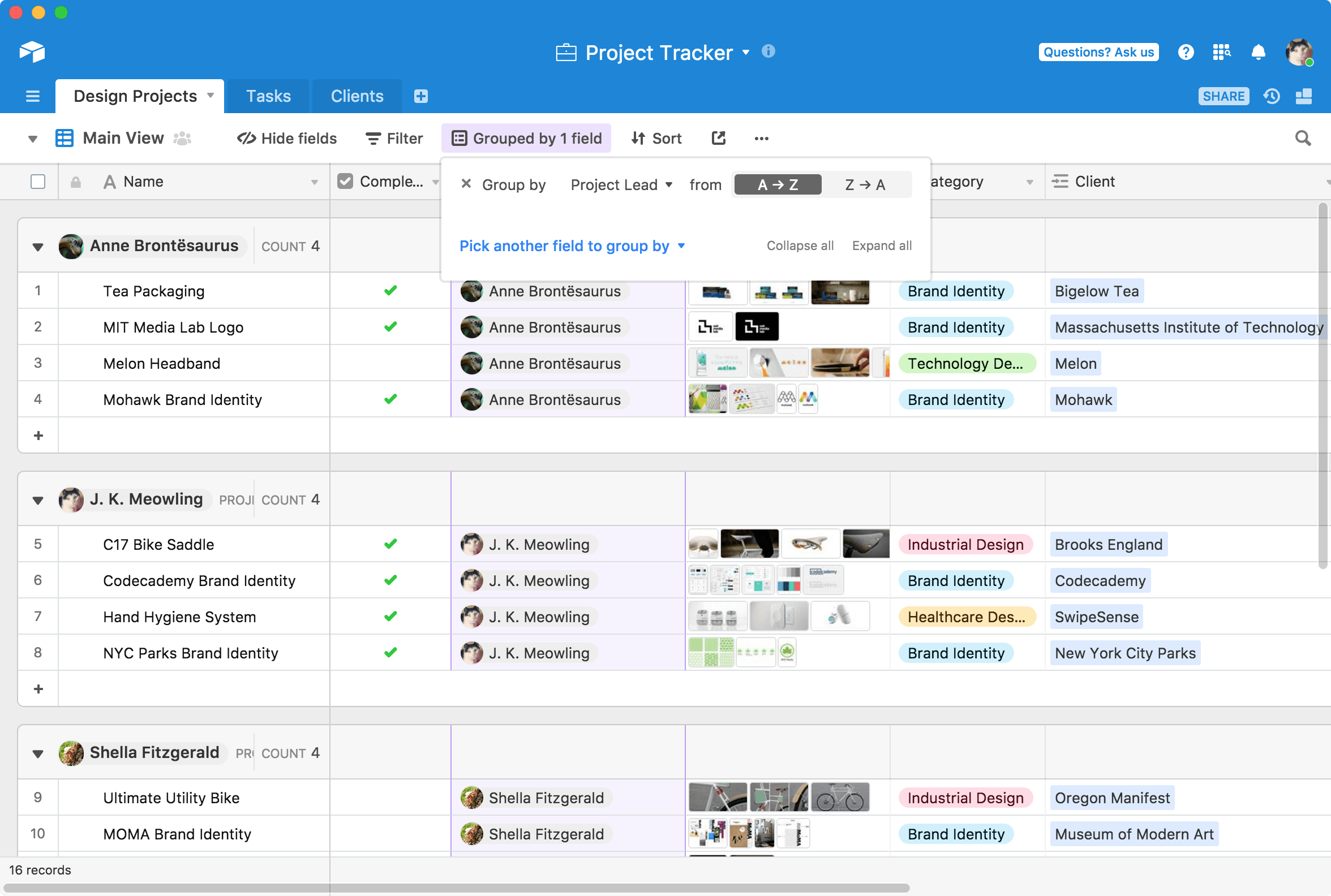

Aside from the launch of its iPad app in July 2016, which had been in beta for some time, the next major improvements to Airtable came in September 2016 with a slew of updates including gallery view, grouped records, another design refresh, as well as native apps for both OS X and Android. Gallery view, in particular, was a significant step forward for Airtable as a product. The feature looked and felt a lot like Pinterest and offered users a familiar grid-based layout of records displayed in large, easily moved tiles. Helpfully, records contained within gallery view could have multiple attachments that could be viewed simply by hovering over that record without needing to expand the view. Although this was a primarily graphical update, it also simplified navigating through complex interrelated records, particularly for collaborative projects across large teams.

Grouped records was a similarly significant update, even if it may not have appeared so at first. Grouped records was a major step forward in making reporting within Airtable easier and more useful. Users could now view custom reports for records grouped by type without the need for pivot tables and other hacks to get around the limitations of reporting on a select number of records. That wasn’t all grouped records was useful for, however. Users could also directly manipulate grouped records within their custom views using Airtable’s familiar drag-and-drop UI. This feature was ideal for users who needed to create and view reports on select records that frequently changed status, such as sales leads progressing through each sales stage or calendar-based events that changed over time.

With each successive update, Airtable became increasingly flexible, diverse, and customizable. This wasn’t just a smart way of appealing to more users; it was another way for Airtable to differentiate itself as a product. Airtable had evolved considerably since its launch, but unlike some products, it hadn’t suffered from feature-creep or bloat. Everything Airtable did made the product more useful and easier to use. Best of all, the features Airtable introduced during this period were equally useful to individuals managing personal projects and to large teams collaborating on complex projects in corporate environments.

This flexibility was part of Airtable’s growth strategy. By giving users the freedom to customize Airtable to suit their individual needs, the company hoped to drive adoption of the product at companies by appealing to individual users, in much the same way that Slack had done for team-based, real-time communication. Many companies overlook fringe use cases as novelties. Airtable saw those outliers as valuable user research that the company could use as the basis of future product development. In a way, this was much closer to open-source product development than the typical top-down strategy favored by legacy tech companies such as Oracle. Combined with Airtable’s commitment to user-friendly design, this was a powerfully effective growth strategy––a strategy so effective that by September 2016, more than 2M Airtable bases had been created.

“Airtable is hoping that people will adopt the app for themselves, and then bring it to their workplace, and vice-versa. To promote such adoption, the startup watches for users coming up with neat ways to use the app, and when it finds something that could be used broadly, adapts the custom solutions made by users into templates that others can build from.” – Kyle Russell on TechCrunch

2016 had been a very busy year for Airtable. After a frantic summer of major updates and minor tweaks and improvements, some companies may have been tempted to rest on their laurels––but not Airtable. Two months after the launch of gallery view and grouped records, Airtable unveiled its most significant update to date: its kanban boards.

By itself, the introduction of kanban boards wasn’t particularly remarkable. It certainly wasn’t intended to be a standalone replacement for the more established Trello or Jira (though Jira’s clunky interface, long the bane of software developers everywhere, was certainly a vulnerability). It did, however, make Airtable even more flexible and diverse. The introduction of Kanban boards combined with its calendar views made Airtable a remarkably powerful organizational tool that could be easily customized and configured to users’ needs––something Airtable had sought to create from the very beginning.

2015 and 2016 were pivotal years for Airtable as a product and a company. It had hit upon a solid idea for a business and attracted sufficient capital to make that idea a reality. However, it was really the product’s design ideology and its willingness to embrace the growing community around the product that helped Airtable find its niche. What the company needed now was to expand, and it would do so by moving more aggressively toward business environments and the enterprise.

2017 – Present: The Building Blocks of Growth

Airtable had spent the previous several years focusing on the feel and design of the product. The company’s willingness to listen to and watch the community around the product had been a fertile lab of creative potential that the company had leveraged to identify new features and potential use cases. What was perhaps most brilliant about Airtable as a product was the fact that it gave non-technical users the power of a relational database with the accessible, consumer-friendly UI of a spreadsheet. However, having accepted a considerable sum in venture capital, the pressure was on to grow even further.

By 2017, Airtable had grown considerably. Although Liu, Ofstad, and the company as a whole had been extraordinarily reluctant to disclose specific growth and revenue data, Airtable appeared to be doing very well. However, to justify the sizable investments that numerous VCs had made in the company, Airtable couldn’t continue appealing to individuals and small teams forever. The company needed to pursue higher revenues more aggressively, which is why Airtable began targeting larger companies and enterprise clients more proactively in 2017.

To raise awareness of Airtable, the company shifted its marketing strategy significantly in 2017 by erecting colorful billboards all over San Francisco and the Bay Area.

For an analog marketing strategy in a major tech hub, it was incredibly effective.

Word soon began to spread in the City by the Bay about Airtable, and even local insiders were surprised by how quickly the company became the latest company to watch. However, the billboard campaign did more than just raise awareness of the product in a vitally important market; it piqued the interest of tech-savvy developers who were sick and tired of the inefficiencies of traditional relational databases.

Just because these individuals had the technical chops to work with databases didn’t mean they liked them.

“It’s crazy how Airtable kind of blew up. All of my developer friends are pretty excited about it.” — Patrick Perini, VP of Product, Mira

Airtable had already won over non-technical users who wanted to build simple, fully featured applications without writing code. Now Airtable was going after the techies who could write code but wanted an easier way to work. This also built on Airtable’s earlier strategy of appealing to individual users who could evangelize about and bring Airtable with them to work and vice-versa.

In terms of pricing, Airtable has long favored an approach favored by many SaaS companies––provide enough value to reach a large potential userbase, but apply just enough pressure to convince users to sign up for a Pro account, which costs $10 per month when billed annually or $12 when billed monthly.

There are enough limitations to Airtable’s free plans to make it impractical for even moderately complex projects:

- Free users are limited to 1,200 records per base.

- File storage is capped at 2GB.

- Free users only have two weeks of revision history/snapshot backups.

- Free users cannot include Blocks in their bases.

- The header images of forms created using free accounts cannot be customized, and Airtable’s branding cannot be removed.

- Free users cannot color-code fields in calendar view.

- Date ranges and multiple date fields are unavailable in calendar view for free users.

Some aspects of the free plan’s limitations are relatively minor inconveniences, such as the restricted file storage. Others, however, are more problematic––at least for users. For example, the limit of just 1,200 records per base is almost punitively harsh, especially when the completely free Google Sheets offers users up to 5M cells, 40,000 rows, and 18,278 columns. Of course, it’s a little unfair to make an apples-to-apples comparison between the two products, but some users were frustrated by the limitations of Airtable’s free plan.

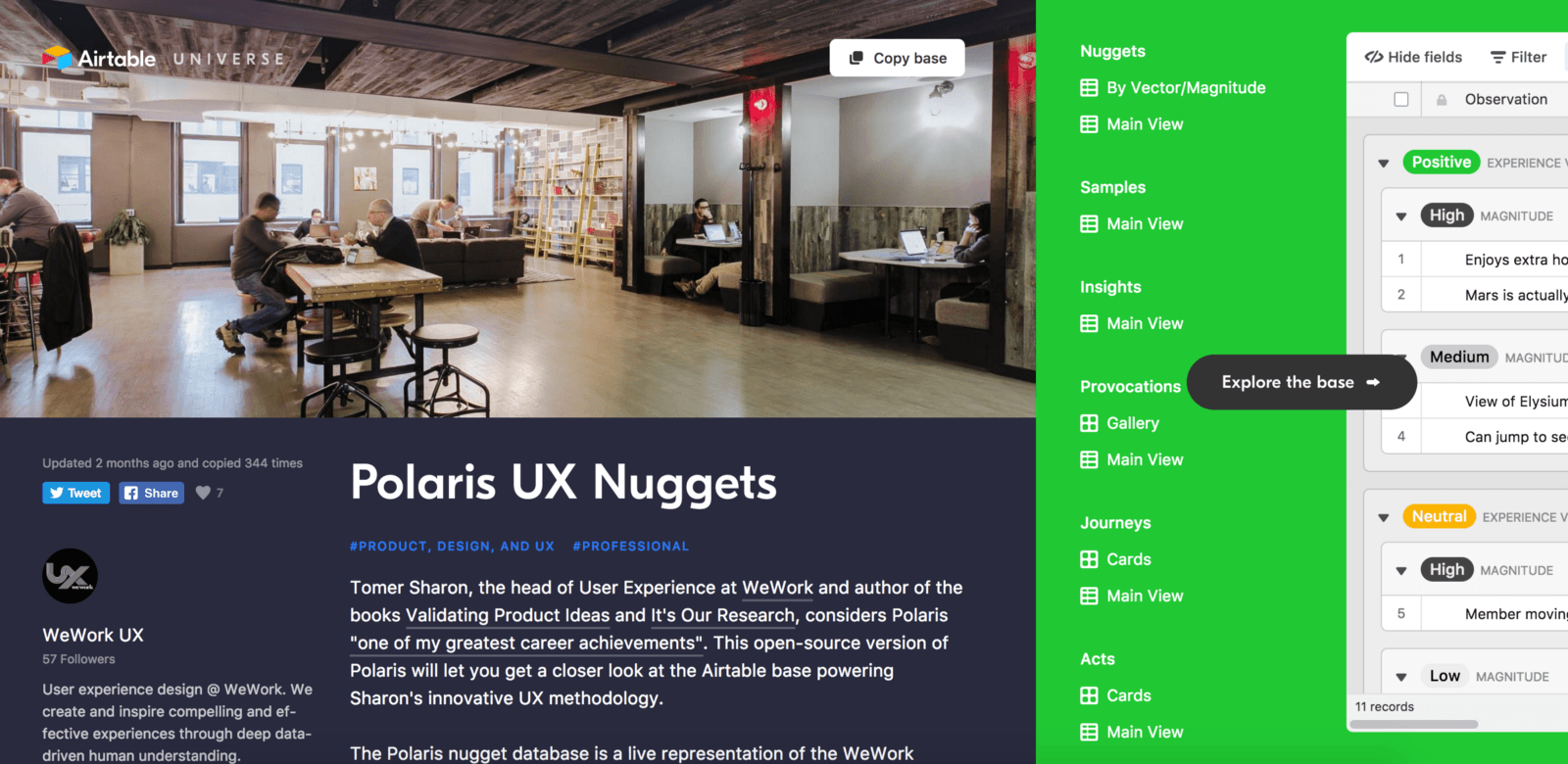

September 2017 saw the release of Airtable Universe, Airtable’s primary learning resource center. One of the most challenging aspects of marketing and selling a flexible tool like Airtable is that people use it for many different things in a lot of different ways. Airtable has horizontal, not vertical, use cases. Airtable Universe was a great way to show all the different ways people were using Airtable using essentially user-generated content. Airtable Universe was designed to not only showcase the many various use cases of the product but to serve as a place where like-minded people could share their workflows and learn from companies that had successfully implemented Airtable into their day-to-day operations.

Airtable Universe featured dozens of real-world applications of the product from the get-go. Best of all, the bases contained within Airtable Universe could be quickly cloned and customized to suit the needs of the user, vastly reducing the time it took to create an Airtable base from scratch. And, as before, it also gave Airtable even greater insight into how people were using the product––a potential goldmine of future feature ideas.

The following month, Airtable redesigned its calendar feature. Although calendar got an aesthetic refresh, the real purpose of the redesign was to implement features that made Airtable more attractive to pro users and teams working at larger companies. A range of improvements was introduced in this update, including the ability to filter views by date range and color-coding for easier subcategorization within views. These features were undoubtedly useful and welcomed by Airtable’s Pro users but were aimed squarely at Airtable’s Enterprise customers.

One of the most significant updates to Airtable as a product came in March 2018 with the release of Blocks, which was a huge step forward for the company. Blocks allow users to customize their bases by adding module-like blocks to their bases. A small, independent logistics company, for example, could track the location of its vehicles much more effectively simply by dragging and dropping a map block into their Airtable base.

Prior to the launch of Blocks, Airtable had been focused on building on top of the grid of the spreadsheet and giving people different ways to visually organize information via views. Blocks added another layer on top of that, which allows people to create custom applications via API services.

“Blocks introduces workflows that were not previously possible—not only on the Airtable platform, but on any platform before. Custom apps that would have, in the past, cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to create and taken months to build … [can] be made in a matter of days by the end users themselves.” — Howie Liu, founder, Airtable

Shortly after the announcement of Blocks, Airtable revealed that it had raised $52M as part of its Series B round, led by previous investors CRV and Caffeinated Capital. The company planned to use the investment to fund further product development and expand its physical footprint by opening an office in New York City.

By this point, Airtable was already being used at some of the most exciting companies in Silicon Valley and beyond, including Airbnb, Conde Nast Entertainment, Penguin Random House, Tesla, and WeWork. The press release accompanying the round claimed the company had more than 30,000 business users alone. However, Liu and the company as a whole remained tight-lipped about specific figures. In an interview with Business Insider, Liu confirmed that Airtable’s userbase was “in the seven digits,” and that year-over-year revenue had increased by more than 500%. The Tesla deal alone was reportedly “in the six figures,” highlighting both the value of Airtable to large companies and the likely trajectory investors would expect from the company moving forward.

“There’s this assumption that software has to involve literally writing code. It’s sort of a difficult thing to extricate ourselves from because we have built so much with writing code. But when you think about what goes into a useful application, especially in the business-to-business internal tools in a company use case which forms the bulk of software that’s consumed in terms of lines of code written, most of them are primarily a relational database model, and the relational database aspect of it is not an arbitrary format.” — Howie Liu, founder, Airtable

In November 2018, Airtable raised $100M as part of its Series C round led by Benchmark and Thrive Capital, which the company would use to expand its physical presence even further by opening additional offices outside the United States. Interestingly, the company’s Series B round gave the company a valuation of just $152M––a figure the company disputed as too low, despite declining to clarify with its own figures. The company’s Series C round, however, gave Airtable a valuation of approximately $1.1B.

One of Airtable’s greatest strengths has always been the sheer diversity of applications it can be used for. However, the company’s horizontal approach of attempting to appeal to many different kinds of users––each with different needs––could also prove to be the company’s biggest weakness. As Airtable has grown, the company has become a much bigger target for companies seeking to build businesses by improving upon select aspects of Airtable’s functionality. The company faces little real competition for now, but the real question is how Airtable will finally achieve profitability and how the company will respond when hungry startups come looking for their piece of the productivity pie.

Where Could Airtable Go from Here?

Over the past several years, Airtable has continually added new features while avoiding that dreaded feeling of feature-creep. However, the company is still not profitable, and investors’ expectations are high. Where could Airtable go from here?

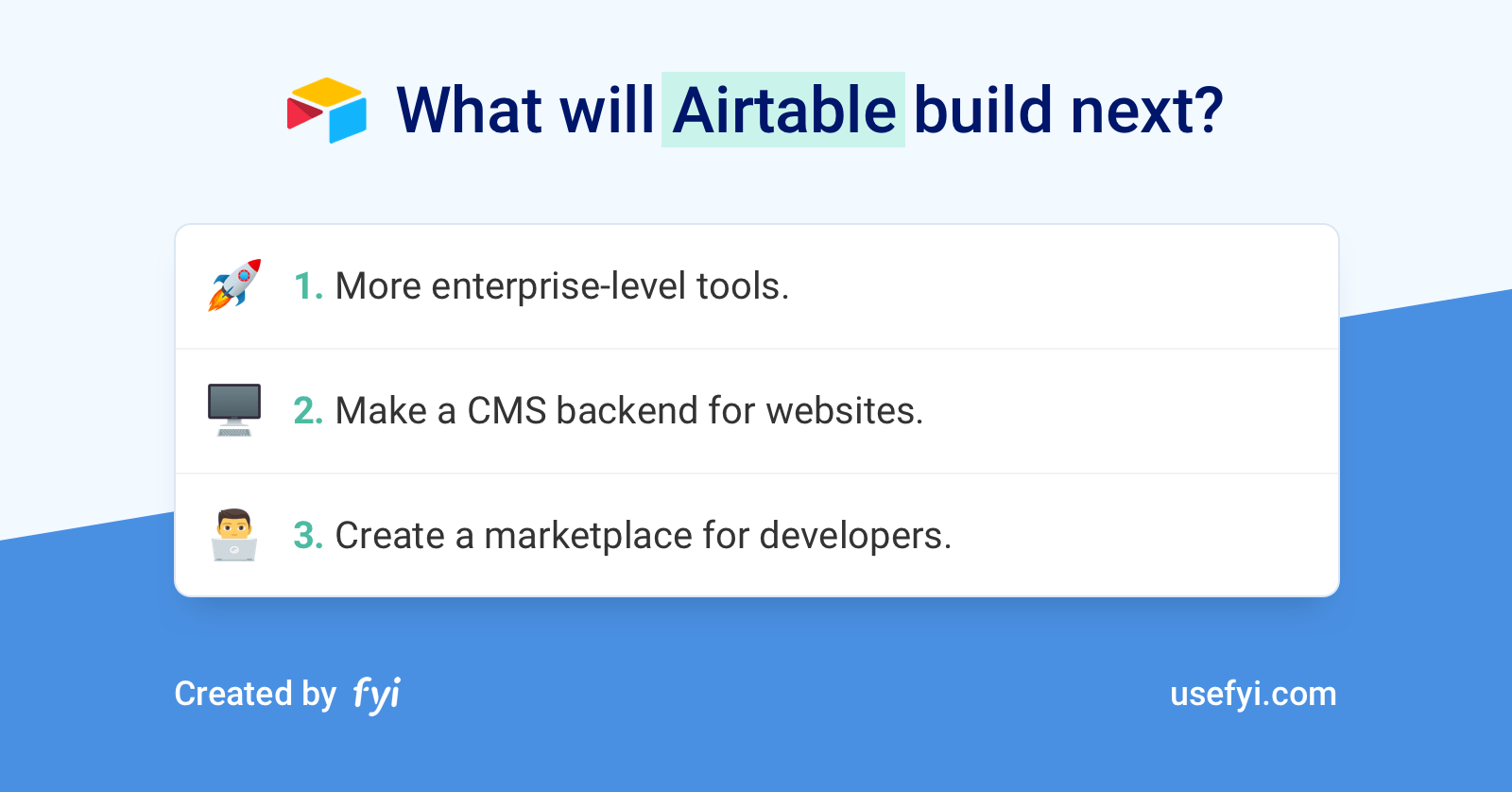

- More enterprise-level tools. Airtable’s power and flexibility have attracted some of the world’s biggest and most exciting companies. A likely move Airtable may make in the future is the development of more specific tools aimed at enterprise clients. This might include a dedicated CRM product or project management tools for larger teams.

- Developing a full-fledged CMS as a back end for websites. Despite the number of CMS products currently available, WordPress still reigns supreme. However, Airtable’s technical expertise and the diversity of its functionality put the company in a very strong position to potentially develop a dedicated CMS that could build upon the product’s core features. Such a move would not only create an additional revenue stream in Airtable’s pursuit of profitability but would also apply pressure on WordPress in terms of market share.

- Creating a marketplace for developers. Airtable Universe is a fantastic showcase of what Airtable can do. One potential move Airtable could make––and has hinted at strongly in the past––is to create a dedicated marketplace where developers can sell apps built directly within Airtable.

What Can We Learn from Airtable?

Airtable is a unique product and its journey so far has been anything but predictable. Despite its curious place in the broader productivity tool ecosystem, there are plenty of lessons that entrepreneurs can apply to their own products and projects. What lessons can we take away from Airtable?

1. Your users are a goldmine for ideas of use cases. One of the smartest decisions Airtable ever made was to watch its users closely and learn from how people were using the product. Had the company not done this, Airtable might lack some of its most popular features and could have gone in an entirely different direction as a product.

Take a look at your own product and consider the following:

- Are you empowering your users to do what they want to do or forcing them to conform to your vision of what your product should be? It’s not without risk to put your users in the driver’s seat, but failing to listen or respond to how users are really using your product could result in missing enormous opportunities.

- What’s one step you could take or feature you could implement to give your users more creative freedom? How might you test this functionality, and how could you evaluate the results?

- What does your user research look like? Are you relying solely on easily available metrics, or are you conducting qualitative research? How could you gain greater insight into your users’ needs and habits?

2. Relying on third-party companies and products to expand your product’s functionality reduces technical overhead considerably, but it’s a risky strategy. Airtable’s impressive range of integrations with other tools was a major plus to early adopters and new users alike. It gave users much more control over how Airtable could integrate into their existing workflows, which was crucial for the product’s early growth. However, Airtable remains almost completely reliant on automation tool Zapier for many of its integrations to work, which could become a crucial vulnerability for Airtable in the future.

If your product offers integrations with other products and services, think carefully:

- Let’s say, for the sake of example, that your own product’s integrations are handled by a service like Zapier. How would you respond if Zapier suddenly announced it was shutting down? Do you have a dedicated emergency response plan in place to handle a situation like this? How long would it take you to build your own integrations?

- How would you inform your users that many of the integrations they had come to rely upon were in jeopardy? What effect might this have on your DAU/MAUs, and how would you mitigate it?

- Are you approaching integrations as a vital element of your product’s broader utility, or are they just “nice to have”?

3. Show users a better way to do what they’re already doing. It’s arguably much easier to gently correct users’ existing behaviors than it is to “teach” them brand-new ones. This is what made Airtable such a brilliant idea. Liu didn’t set out with a solution in search of a problem––he targeted an existing problem (the limitations of spreadsheets) and an existing behavior (people using spreadsheets as purely organizational tools), and ultimately solved both.

Think back to when you originally devised the idea for your product:

- What inspired you to tackle this problem? Did you spot a gap in an existing market (in Airtable’s case, the common misuse of productivity software), or were you convinced that people would come to appreciate a new take on a familiar problem?

- Are you leveraging existing behaviors in your product? If so, how––and if not, why not?

- Airtable smartly incorporated the problem it aimed to solve into its messaging early on, which simplified the concept of what Airtable is for many users. What would this look like if you were to do the same? How could you position your product in a way that most people would grasp quickly?

Masters of the (Airtable) Universe

Lots of products take innovative approaches to solving common problems. Few have done so in such an interesting way as Airtable. Despite taking more than a few risks with its development, Airtable has emerged as one of the most genuinely diverse and versatile SaaS products on the market, and Liu has remained true to his original vision––not an easy feat, as any entrepreneur could tell you.

Airtable might not yet be profitable, but that hasn’t stopped other companies from forging ahead into the future. I, for one, can’t wait to see what Airtable does next.

Do you use Airtable? You can find your Airtable documents, alongside documents from other apps, in 3 clicks or less by using FYI.